Transportation Energy Futures: Project Overview and Findings

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fuel Dealer Supplemental Application

FUEL DEALER SUPPLEMENTAL APPLICATION Applicant: Address: Owner and/or Manager responsible for daily operations: Website: FEIN: US DOT #: Date established: Proposed policy effective date: Business type: Sole Proprietor C-Corporation S-Corporation Partnership Current Carrier Line of Coverage Current Premiums Business Operations (check all that apply) Auto Service & Repair Convenience Stores HVAC Installation or Repair Bulk Oil Sales Fuel Distributor/Dealer LP Bulk Storage Bulk Storage (gas, diesel) Home Heating Fuel Propane Distributor Common Carrier Other: 1. Any other entities, subsidiaries, joint ventures or partnerships associated with applicant? Yes No 2. What is the name and title of individual responsible for safety program? How many years of experience in this role? Contact information: SECTION I – FUEL DEALER GENERAL INFORMATION 1. How many years has current management been in place? 2. Has there been a merger or acquisition with another business entity within the past 3 years? Yes No 3. Does the Applicant have formal hiring practices to include: a. Documented interviews? Yes No b. Formal background checks? Yes No c. Reference checks? Yes No 4. Does the Applicant business include any of the following: a. Any fuel brought in by or delivered to boats or barges? Yes No b. Any hauling, storage, and/or disposal of waste oil, pool water, or asphalt? Yes No c. Any sale of racing fuel? Yes No If Yes: % d. Any direct fueling of aircraft? Yes No e. Any direct fueling of watercraft? Yes No f. Any direct fueling of locomotives? Yes No g. Any operations involving anhydrous ammonia? Yes No h. Any operations related to converting vehicles to propane power for Applicant’s use or other’s? Yes No i. -

Biomass Basics: the Facts About Bioenergy 1 We Rely on Energy Every Day

Biomass Basics: The Facts About Bioenergy 1 We Rely on Energy Every Day Energy is essential in our daily lives. We use it to fuel our cars, grow our food, heat our homes, and run our businesses. Most of our energy comes from burning fossil fuels like petroleum, coal, and natural gas. These fuels provide the energy that we need today, but there are several reasons why we are developing sustainable alternatives. 2 We are running out of fossil fuels Fossil fuels take millions of years to form within the Earth. Once we use up our reserves of fossil fuels, we will be out in the cold - literally - unless we find other fuel sources. Bioenergy, or energy derived from biomass, is a sustainable alternative to fossil fuels because it can be produced from renewable sources, such as plants and waste, that can be continuously replenished. Fossil fuels, such as petroleum, need to be imported from other countries Some fossil fuels are found in the United States but not enough to meet all of our energy needs. In 2014, 27% of the petroleum consumed in the United States was imported from other countries, leaving the nation’s supply of oil vulnerable to global trends. When it is hard to buy enough oil, the price can increase significantly and reduce our supply of gasoline – affecting our national security. Because energy is extremely important to our economy, it is better to produce energy in the United States so that it will always be available when we need it. Use of fossil fuels can be harmful to humans and the environment When fossil fuels are burned, they release carbon dioxide and other gases into the atmosphere. -

Fuel Properties Comparison

Alternative Fuels Data Center Fuel Properties Comparison Compressed Liquefied Low Sulfur Gasoline/E10 Biodiesel Propane (LPG) Natural Gas Natural Gas Ethanol/E100 Methanol Hydrogen Electricity Diesel (CNG) (LNG) Chemical C4 to C12 and C8 to C25 Methyl esters of C3H8 (majority) CH4 (majority), CH4 same as CNG CH3CH2OH CH3OH H2 N/A Structure [1] Ethanol ≤ to C12 to C22 fatty acids and C4H10 C2H6 and inert with inert gasses 10% (minority) gases <0.5% (a) Fuel Material Crude Oil Crude Oil Fats and oils from A by-product of Underground Underground Corn, grains, or Natural gas, coal, Natural gas, Natural gas, coal, (feedstocks) sources such as petroleum reserves and reserves and agricultural waste or woody biomass methanol, and nuclear, wind, soybeans, waste refining or renewable renewable (cellulose) electrolysis of hydro, solar, and cooking oil, animal natural gas biogas biogas water small percentages fats, and rapeseed processing of geothermal and biomass Gasoline or 1 gal = 1.00 1 gal = 1.12 B100 1 gal = 0.74 GGE 1 lb. = 0.18 GGE 1 lb. = 0.19 GGE 1 gal = 0.67 GGE 1 gal = 0.50 GGE 1 lb. = 0.45 1 kWh = 0.030 Diesel Gallon GGE GGE 1 gal = 1.05 GGE 1 gal = 0.66 DGE 1 lb. = 0.16 DGE 1 lb. = 0.17 DGE 1 gal = 0.59 DGE 1 gal = 0.45 DGE GGE GGE Equivalent 1 gal = 0.88 1 gal = 1.00 1 gal = 0.93 DGE 1 lb. = 0.40 1 kWh = 0.027 (GGE or DGE) DGE DGE B20 DGE DGE 1 gal = 1.11 GGE 1 kg = 1 GGE 1 gal = 0.99 DGE 1 kg = 0.9 DGE Energy 1 gallon of 1 gallon of 1 gallon of B100 1 gallon of 5.66 lb., or 5.37 lb. -

Electricity Production by Fuel

EN27 Electricity production by fuel Key message Fossil fuels and nuclear energy continue to dominate the fuel mix for electricity production despite their risk of environmental impact. This impact was reduced during the 1990s with relatively clean natural gas becoming the main choice of fuel for new plants, at the expense of oil, in particular. Production from coal and lignite has increased slightly in recent years but its share of electricity produced has been constant since 2000 as overall production increases. The steep increase in overall electricity production has also counteracted some of the environmental benefits from fuel switching. Rationale The trend in electricity production by fuel provides a broad indication of the impacts associated with electricity production. The type and extent of the related environmental pressures depends upon the type and amount of fuels used for electricity generation as well as the use of abatement technologies. Fig. 1: Gross electricity production by fuel, EU-25 5,000 4,500 4,000 Other fuels 3,500 Renewables 1.4% 3,000 13.7% Nuclear 2,500 TWh Natural and derived 31.0% gas 2,000 Coal and lignite 1,500 19.9% Oil 1,000 29.5% 500 4.5% 0 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2010 2020 2030 Data Source: Eurostat (Historic data), Primes Energy Model (European Commission 2006) for projections. Note: Data shown are for gross electricity production and include electricity production from both public and auto-producers. Renewables includes electricity produced from hydro (excluding pumping), biomass, municipal waste, geothermal, wind and solar PV. -

Hydroelectric Power -- What Is It? It=S a Form of Energy … a Renewable Resource

INTRODUCTION Hydroelectric Power -- what is it? It=s a form of energy … a renewable resource. Hydropower provides about 96 percent of the renewable energy in the United States. Other renewable resources include geothermal, wave power, tidal power, wind power, and solar power. Hydroelectric powerplants do not use up resources to create electricity nor do they pollute the air, land, or water, as other powerplants may. Hydroelectric power has played an important part in the development of this Nation's electric power industry. Both small and large hydroelectric power developments were instrumental in the early expansion of the electric power industry. Hydroelectric power comes from flowing water … winter and spring runoff from mountain streams and clear lakes. Water, when it is falling by the force of gravity, can be used to turn turbines and generators that produce electricity. Hydroelectric power is important to our Nation. Growing populations and modern technologies require vast amounts of electricity for creating, building, and expanding. In the 1920's, hydroelectric plants supplied as much as 40 percent of the electric energy produced. Although the amount of energy produced by this means has steadily increased, the amount produced by other types of powerplants has increased at a faster rate and hydroelectric power presently supplies about 10 percent of the electrical generating capacity of the United States. Hydropower is an essential contributor in the national power grid because of its ability to respond quickly to rapidly varying loads or system disturbances, which base load plants with steam systems powered by combustion or nuclear processes cannot accommodate. Reclamation=s 58 powerplants throughout the Western United States produce an average of 42 billion kWh (kilowatt-hours) per year, enough to meet the residential needs of more than 14 million people. -

3 Metered Fuel Consumption.Docx

Report 3: Metered fuel consumption Including annex on high energy users Prepared by BRE on behalf of the Department of Energy and Climate Change December 2013 BRE report number 286734 The EFUS has been undertaken by BRE on behalf of the Department of Energy and Climate Change (DECC). Report editors and lead authors: Jack Hulme, Adele Beaumont and Claire Summers. Project directed by: John Riley and Jack Hulme. Data manager: Mike Kay. Supporting authors and analysts: Mike Kay, Busola Siyanbola, Tad Nowak, Peter Iles, Andrew Gemmell, John Hart, John Henderson, Afi Adjei, Lorna Hamilton, Caroline Buchanan, Helen Garrett, Charlotte Turner, Sharon Monahan, Janet Utley, Sara Coward, Vicky Yan & Matt Custard. Additional thanks to the wider team of reviewers and contributors at BRE, DECC and elsewhere, including GfK NOP Social Research, Gemini Data Loggers, Consumer Futures, G4S, Eon, British Gas, and for the input of the Project Steering Group and Peer Reviewers. Executive Summary This report presents the results from an analysis of the median gas and electricity consumptions derived from the 2011 Energy Follow-Up Survey (EFUS). The 2011 EFUS consisted of a follow-up interview survey and associated monitoring of a sub-set of households first visited as part of the 2010/2011 English Housing Survey (EHS). Analysis is based on the meter reading sub-sample weighted to the national level, using a weighting factor specific to the meter reading sub-sample. The results presented in this report are therefore representative of the English housing stock, with a population of 21.9 million households. § The meter reading data reveals a wide range in energy consumption across the household stock1. -

On Alternative Energy Hydroelectric Power

Focus On Alternative Energy Hydroelectric Power What is Hydroelectric Power (Hydropower)? Hydroelectric power comes from the natural flow of water. The energy is produced by the fall of water turning the blades of a turbine. The turbine is connected to a generator that converts the energy into electricity. The amount of electricity a system can produce depends on the quantity of water passing through a turbine (the volume of water flow) and the height from which the water ‘falls’ (head). The greater the flow and the head, the more electricity produced. Why Wind? Hydropower is a clean, domestic, and renewable source of energy. It provides inexpensive electricity and produces no pollution. Unlike fossil fuels, hydropower does not destroy water during the production of electricity. Hydropower is the only renewable source of energy that can replace fossil fuels’ electricity production while satisfying growing energy needs. Hydroelectric systems vary in size and application. Micro-hydroelectric plants are the smallest types of hydroelectric systems. They can generate between 1 kW and 1 MW of power and are ideal for powering smaller services such as processing machines, small farms, and communities. Large hydroelectric systems can produce large amounts of electricity. These systems can be used to power large communities and cities. Why Hydropower? Technical Feasibility Hydropower is the most energy efficient power generator. Currently, hydropower is capable of converting 90% of the available energy into electricity. This can be compared to the most efficient fossil fuel plants, which are only 60% efficient. The principal advantages of using hydropower are its large renewable domestic resource base, the absence of polluting emissions during operation, its capability in some cases to respond quickly to utility load demands, and its very low operating costs. -

Scooptram® ST710 Technical Specification

Atlas Copco Underground Loaders Scooptram® ST710 Technical specification The ST710 is a compact 6.5 metric ton Scooptram with an ergonomically designed operator’s compartment especially for narrow-vein mining. Features Load frame Power frame • A Z-bar front-end for efficient loading and mucking • Atlas Copco unique powertrain including an upbox, and • An aggressively designed “high shape” factor bucket, re- a transverter (a combined transmission and converter) - ducing the need for multiple passes to fill the bucket allowing space for the “footbox” plus a low and short rear • Easy to change bucket and cylinders with split-cap pin end retention system • Electronic transverter and engine control systems for • Boom support and lock for safe work under boom smooth and precise shifting • A high power-to-weight ratio complemented by a fully Operator’s compartment integrated powertrain, automatically matching the gear Ergonomically and spacious designed compartment for selection to the load - producing a high tractive effort maximum safety and minimal operator fatigue with: without wheel spin • maximized legroom because of the Atlas Copco’s • Stacked V-core radiator and charge air cooler: easy to re- “footbox” place damaged tubes and to clean • comfortable operator’s seat offering improved ergonomic positioning, body orientation and generous shoulder and General hip room • Great serviceability with centralized service points • compliant with sound and vibration regulations to mini- • Long-life roller bearing centre hinge mize operator’s fatigue; -

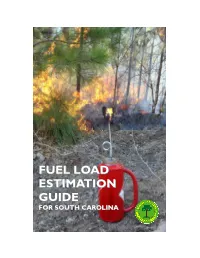

FUEL LOAD ESTIMATION GUIDE for South Carolina

For Prescribed Burning In South Carolina FUELFUEL LOADLOAD ESTIMATIONESTIMATION GUIDEGUIDE FOR SOUTH CAROLINA FOR SOUTH CAROLINA FUEL LOAD ESTIMATION GUIDE for South Carolina To comply with Smoke Management Guidelines for VegetaƟve Debris Burning OperaƟons in the State of South Carolina, land managers that ulize prescribed fire to accomplish resource objecves for agriculture, wildlife management, or forest management purposes are required to esmate the tons of fuel that will be consumed on each site when making noficaon to the SC Forestry Commission. Esmang the total tons of fuel present on the site is oen difficult for novice burners. This guide was developed to provide a visual reference for burners to aid them in the fuel load esmaon process. The photographs in this document were taken during a fuel load study conducted by the SC Forestry Commission. In the study, plots were taken in various fuel types across the state. In each plot, the vegetaon and lier were collected, oven dried, and weighed to calculate the total tons per acre on each study site. To accurately esmate fuel loading: Choose a fuel type from the fuel loading chart or from the photos provided that most closely matches the fuels present in the area you plan to burn. The fuel type used to esƟmate fuel loading should represent the fuel on site that will be the main carrier of the fire. Using the Typical Fuel Loadings chart (available in this reference guide or in the Smoke Management Guidelines) or the reference photos in this document, decide if the site you plan to burn has 1 Low, Medium, or High fuel loading. -

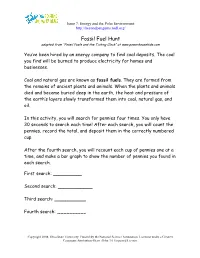

Fossil Fuel Hunt Adapted from “Fossil Fuels and the Ticking Clock” At

Issue 7: Energy and the Polar Environment http://beyondpenguins.nsdl.org/ Fossil Fuel Hunt adapted from “Fossil Fuels and the Ticking Clock” at www.powerhousekids.com You’ve been hired by an energy company to find coal deposits. The coal you find will be burned to produce electricity for homes and businesses. Coal and natural gas are known as fossil fuels. They are formed from the remains of ancient plants and animals. When the plants and animals died and became buried deep in the earth, the heat and pressure of the earth’s layers slowly transformed them into coal, natural gas, and oil. In this activity, you will search for pennies four times. You only have 30 seconds to search each time! After each search, you will count the pennies, record the total, and deposit them in the correctly numbered cup. After the fourth search, you will recount each cup of pennies one at a time, and make a bar graph to show the number of pennies you found in each search. First search: __________ Second search: ____________ Third search: ___________ Fourth search: __________ Copyright 2008: Ohio State University. Funded by the National Science Foundation. Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License. Issue 7: Energy and the Polar Environment http://beyondpenguins.nsdl.org/ 45 35 Number of pennies found 25 15 5 1st 2nd 3rd 4th search search search search Questions: 1. In which search did you find the most pennies? 2. In which search did you find the least pennies? 3. Why do you think it became increasingly harder to find pennies? 4. -

Fossil Fuels? Beside Each Sentence Below, Write Down Whether It Is Talking About Coal, Oil, Or Natural Gas

Puzzles & Word Games Coal, Oil or Natural Gas? How well do you know your fossil fuels? Beside each sentence below, write down whether it is talking about coal, oil, or natural gas. Watch out! Some may have more than one answer. Name the Fossil Fuel 1. There is probably enough of this fossil fuel to last another 200 years. 2. Started out as plankton (tiny plants and animals) millions of years ago. 3. This fossil fuel provides about 40% of the world’s energy. 4. In its early stages this fossil fuel is a spongy brown material called peat. 5. This fossil fuel provides about 40% of the world's electricity. 6. This fossil fuel produces more carbon dioxide than any other fossil fuel. 7. Before people can use this fossil fuel it is cleaned and separated at a special factory called a refinery. 8. Using this fossil fuel contributes to global warming. 9. More than half of this fossil fuel comes from the Middle East. 10. This fossil fuel burns the hottest, which makes it the most efficient for making electricity. ecokids.ca Puzzles & Word Games Coal, Oil or Natural Gas? How well do you know your fossil fuels? Beside each sentence below, write down whether it is talking about coal, oil, or natural gas. Watch out! Some may have more than one answer. Name the Fossil Fuel Coal 1. There is probably enough of this fossil fuel to last another 200 years. Oil & Natural gas 2. Started out as plankton (tiny plants and animals) millions of years ago. -

Introduction to Fusion Energy

Introduction to Fusion Energy Jerry Hughes IAP @ PSFC January 8, 2013 Acknowledgments: Catherine Fiore, Jeff Freidberg, Martin Greenwald, Zach Hartwig, Alberto Loarte, Bob Mumgaard, Geoff Olynyk Presenter’s e-mail: [email protected] Questions to answer • What is fusion? • Why do we need it? • How do we get it on earth? • Where do we stand? • Where are we headed? What is fusion, anyway? What is fusion, anyway? What is fusion, anyway? What is fusion, anyway? Fusion is a form of nuclear energy E mc2 • A huge amount of energy is released when isotopes lighter than iron combine to form heavier nuclei, with less final mass • It is an ubiquitous energy source in the universe • It is not (yet) a practical energy source on earth Fusion is a form of nuclear energy E mc2 • A huge amount of energy is released when isotopes lighter than iron combine to form heavier nuclei, with less final mass • It is an ubiquitous energy source in the universe • It is not (yet) a practical energy source on earth Terrestrial energy sources have their origin in the nuclear fusion reactions of stars Supernova produces radioactive elements Solar heating of the Earth drives atmospheric circulation, water cycle Sun illuminates Earth Terrestrial energy sources have their origin in the nuclear fusion reactions of stars Geothermal Decay of radioactive particles generates heat in Earth’s interior Nuclear fission Supernova produces radioactive elements Splitting radioactive particles generates heat Solar heating of the Earth drives atmospheric circulation, water cycle