4-9-Rimmer.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

South Ribble WW1 Memorial - 2018 Review

South Ribble WW1 Memorial 2018 Review By Charles O’Donnell WFA Leyland & Central Lancashire southribble-greatwar.com South Ribble WW1 Memorial - 2018 Review South Ribble WW1 Memorial – 2018 Review By Charles O’Donnell © WFA Leyland & Central Lancashire 2018 Cover photograph courtesy of South Ribble Borough Council All other images complimenting the text © Charles O’Donnell 2 South Ribble WW1 Memorial - 2018 Review Table of Contents 2015 – Making a New Memorial............................................................................................................ 5 Qualifying .................................................................................................................................................... 8 Source Materials ........................................................................................................................................ 9 Acknowledgements................................................................................................................................. 16 Roll of Honour - A ................................................................................................................................... 17 Roll of Honour - B .................................................................................................................................... 21 Roll of Honour - C .................................................................................................................................... 41 Roll of Honour - D .................................................................................................................................. -

Preferred Options

Preferred Options Site Allocations and Development Management Policies Development Plan Document – Appendices November/December 2011 C O N T E N T S Appendix 1 – Development Management Policies ......................................................1 Appendix 2 – Preferred Sites To Be Taken Forward .................................................11 Appendix 3 – Proposed Sites Not To Be Taken Forward ..........................................19 Appendix 4a – Central Lancashire Submission Core Strategy, Infrastructure Delivery Schedule Tables....................................................................................22 Appendix 4b – South Ribble Infrastructure, taken from the Central Lancashire Submission Core Strategy, Infrastructure Delivery Schedule (Appendix 4a).......30 Appendix 5 – Retail Maps..........................................................................................33 Leyland.................................................................................................................. 33 Penwortham .......................................................................................................... 34 Bamber Bridge....................................................................................................... 35 Tardy Gate............................................................................................................. 36 Longton.................................................................................................................. 37 Kingsfold............................................................................................................... -

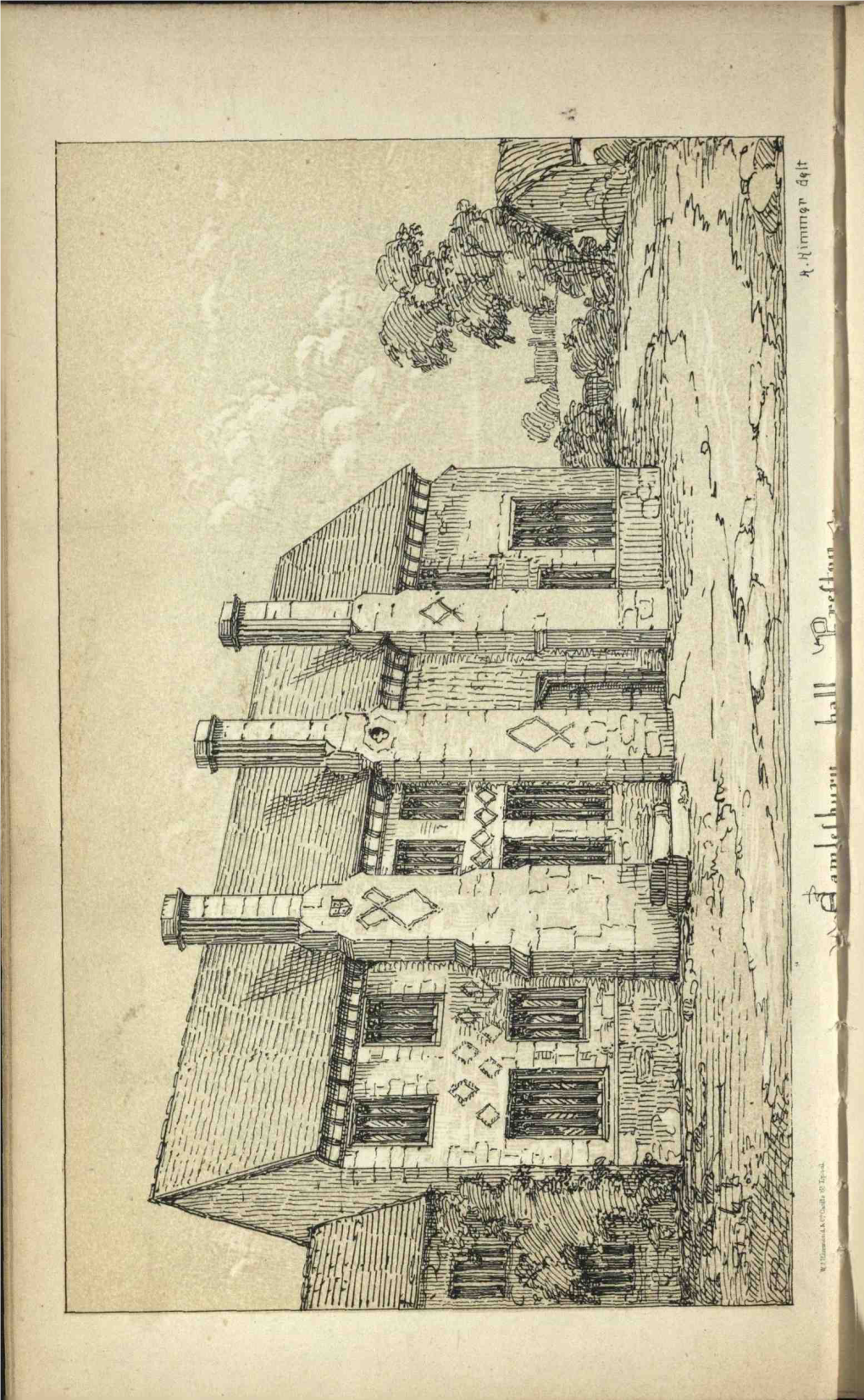

Lancashire Enterprise Zone, Bae Samlesbury, Lancashire

LANCASHIRE ENTERPRISE ZONE, BAE SAMLESBURY, LANCASHIRE Archaeological Evaluation Report Oxford Archaeology North January 2015 Lancashire County Council Issue No: 2014-15/1603 OA North Job No: L10808 NGR: SD 626 314 Lancashire Enterprise Zone, BAE Samlesbury, Lancashire: Archaeological Evaluation 1 CONTENTS LIST OF PLATES ..............................................................................................................3 SUMMARY .......................................................................................................................4 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS...................................................................................................6 1. INTRODUCTION ..........................................................................................................7 1.1 Circumstances of Project ....................................................................................7 1.2 Location, Topography and Geology ...................................................................7 1.3 Historical Background ........................................................................................8 1.4 Map Regression ................................................................................................10 1.5 Census Returns..................................................................................................21 1.6 The Development of the Samlesbury Area and Investigation Sites in the Post- Medieval Period ............................................................................................................22 -

Central Lancashire Employment Land Study – Key Issues Report Chorley, Preston and South Ribble Councils

Central Lancashire Employment Land Study – Key Issues Report Chorley, Preston and South Ribble Councils S153(e)/ Key Issues Report – Final Report/November 2017/BE Group Central Lancashire Employment Land Study – Key Issues Report Chorley, Preston and South Ribble Councils CONTENTS 1.0 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................ 1 2.0 CENTRAL LANCASHIRE IN CONTEXT ..................................................................... 3 4.0 THE MARKET CONTEXT ........................................................................................ 11 5.0 GROWTH FORECASTS – JOBS ............................................................................. 17 6.0 OBJECTIVELY ASSESSED NEEDS ........................................................................ 21 7.0 EMPLOYMENT LAND and PREMISES SUPPLY ..................................................... 26 8.0 RECOMMENDATIONS ............................................................................................ 32 9.0 COMMERCIAL HEADLINES .................................................................................... 37 S153(e)/ Key Issues Report – Final Report/November 2017/BE Group Central Lancashire Employment Land Study – Key Issues Report Chorley, Preston and South Ribble Councils 1.0 INTRODUCTION Introduction 1.1 This Key Issues Report provides a synopsis of the key findings of the Employment Land Study for the Central Lancashire sub-region of Chorley, Preston and South Ribble (see Figure 1). It was -

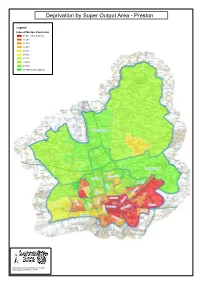

Deprivation by Super Output Area - Preston

Deprivation by Super Output Area - Preston Legend Index of Multiple Deprivation 0-10% Most Deprived 10-20% 20-30% 30-40% 40-50% 50-60% 60-70% 70-80% 80-90% 90-100% Least Deprived Preston Rural North Preston Rural East Sharoe Green Greyfriars Garrison College Ingol Cadley Brookfield Moor Park Larches Deepdale Ashton Tulketh Lea University Ribbleton St. George's St. Matthew's Fishwick Riversway Town Centre ± This map is reproduced from Ordnance Survey material with the permission of Ordnance Survey on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office Crown copyright. Unauthorised reproduction may lead to prosecution or civil proceedings. Lancashire County Council – OS Licence 100023320 2004 )" Childcare Providers(! and Super Output Areas - Preston +$ Legend *# ^_ Childrens Centre Preston District Boundary Wards 2003 )" )" Childminder )"(! "/ Sessional Provision "/ +$ Holiday Club )" *# )" *#)"(! *# Full Day Care *# )" (! )" (! Breakfast Club (! After School Club "/)" "/ LSOA_Centre_Mapping$.IMD_Group )" (!*# 0-10% Most Deprived )" 10-20% 20-30% 30-40% "/ )" )" 40-50%*# )" 50-60% )" 60-70% *# +$ 70-80% 80-90% )" 90-100% Least Deprived $ )" )"+ " )" ) *# )" )" )" (!*# +$)" (!*# (!)" (!*#"/ (!^_ (!(!*#+$ (!)" )" )" )" (!(! )" )")" )" (!"/ )" (! (! *# )" )" " (! ) (!"/" *#" )" (! )" ) ) )" )" )" )")" (!*# )" )" (!(! )" )")" *# *# *# )" $ "/ )" *# )" (!*#+ )")" )" ! " )" (! +$ (! ( ) " )" *#*# ! )" )" +$"/ ) )" (! (! )" )" !( *# *#)" (! "/ *# (!)" ( )" (! )""/ )" ^_)" (! )" "/ )"" )" (!*# *# )" *# ) )" )" ^_(! *#)" " *#+$"/ "/ )" -

Newspapers, Literary Institutions, &:E

PRESTON: Little Hoole, Longton, Much Hoole, Penwortham, Pl'eston, Rib bleton, Ribchester, Samlesbury, 'Valton-Ie-Dale, Whittingham, and Woodplumpton, which contained, in 1851, a population of 96,368 souls. It is divided into the six districts of Preston (east and west), Alston, Broughton, Longton, and Walton. There has been no new workhouse erected for this union, the five old ones being made to do duty in its stead. Their situations are Preston, 1Val ton, Penwortham, W oodplumpton, and Ribchester. The Preston workhouse occupies an airy and healthful situation in Deepdale road, a short dist,ance N.N.E. of the town, and a handsome erection, called" The Overseers' Buildings," was raised in 1848, at the corner of Saul-street and Lancaster-road, for the use of the officers of th& union. The guardians meet at the board-room here every Tuesday, at ten o'clock. Thomas Batty Addison, Esq., is chairman, and Thomas Birchall and Michael Satterthwaite, Esqrs., are vice chairmen; J oseph Thackeray, Esq., is clerk to the union and superintendent registrar. Among the Provident Institutions of Preston are many Friendly Societies, Lodges of Oddfellows, Foresters, Mechani.Js, Druids, Freemasons, the Catholic Brethren, Guilds, &0. The Sav'ing8~ Bank is also a provident institution, which affords a safe and bene cial investment for the savings of the humbler classes, and was first established at the National School here on the 11th of l"Iarch, 1816, but was removed to more convenient premises in Chapel street, in 1818. It now occupies a neat building in Lune-street, erected about seventeen years ago, but was removed to that street in 1830; and in 1852 possessed deposits, amounting to £170,298 4s. -

Bus Travel to Myerscough College 2019-2020 Academic Year

from September 2019 Bus Travel to Myerscough College 2019-2020 academic year Daily direct services from: • Charnock Richard • Chorley • Clayton Brook • Bamber Bridge (Service 125C) • Clitheroe • Whalley • Longridge • Goosnargh • Burnley • Accrington • Blackburn • Samlesbury • Broughton • Fleetwood • Cleveleys • Blackpool • Poulton • St Annes • Lytham • Warton • Freckleton • Kirkham • Preston • Fulwood • Broughton • Ingol • Inskip • Elswick • Great Eccleston Connections from: • Lancaster • Fylde Coast & Morecambe • South Ribble • Bolton • Horwich & South Preston • Chorley • Bamber Bridge SERVICES AVAILABLE TO ALL Including NoWcard Holders board and alight at any recognised bus stops along routes Services Clitheroe, Whalley, Longridge, Goosnargh to Myerscough: Preston Bus 995 Burnley, Accrington, Blackburn, Samlesbury, Broughton to Myerscough: Transdev 852 Lancaster & Morecambe: Stagecoach 40/41 (alight at Barton Grange Garden Centre or Roebuck, catch Free Shuttle Bus service* 401 to Myerscough) Bolton, Horwich, Chorley, Clayton-le-Woods, Bamber Bridge, Longridge: Scheme passes valid for use on any South Ribble and South Preston Stagecoach services, including 2, 3, 109, 113, 125, 61, 68 to Preston Bus Station, then catch Stagecoach 125C or Preston Bus 437 to Myerscough. Fleetwood, Cleveleys, Blackpool, Poulton to Myerscough: Preston Bus 400. Links with Fylde Coast Network at Poulton. St Annes, Lytham, Warton, Freckleton, Kirkham to Myerscough: Preston Bus 853 Preston, Fulwood, Broughton to Myerscough: Preston Bus 437 Preston, Fulwood, Broughton -

The Lost Orchards of Farington Joan Langford Extract from Leyland St Andrew' S Parish Magazine - 37 Shirley Robson March 1906

Lailand Chronicle No. 52 LEYLAND HISTORICAL SOCIETY (Founded 1968) Registered Charity No. 1024919 PRESIDENT Mr W E Waring CHAIR VICE-CHAIR Mr P Houghton Mrs E F Shorrock HONORARY SECRETARY HONORARY TREASURER Mr M J Park Mr E Almond (01772) 437258 AIMS To promote an interest in History generally and that of the Leyland area in particular MEETINGS Held on the first Monday of each month (September to July inclusive) at 7.30 pm (Meeting date may be amended by statutory holidays) in PROSPECT HOUSE, SANDY LANE, LEYLAND SUBSCRIPTIONS Vice Presidents £10.00 per annum Members £8.00 per annum School Members £0.50 per annum Casual Visitors £2.00 per meeting A MEMBER OF THE LANCASHIRE LOCAL HISTORY FEDERATION THE HISTORIC SOCIETY OF LANCASHIRE AND CHESHIRE and THE BRITISH ASSOCIATION FOR LOCAL HISTORY Visit the Leyland Historical Society’s Website at http/www.houghton59.fsnet.co.uk/Home%20Page.htm 3 Lailand Chronicle No. 52 Contents Page Title Contributor 5 Editorial Mary Longton 6 Society Affairs Peter Houghton 8 Obituary - George Leslie Bolton David Hunt 11 The Ship Inn, Leyland, 1851 - 1893 Derek Wilkins 15 Did you know my Great-great-great-grandfather Peter Houghton Bobby Bridge - One-armed Postman, Dentist and Race 19 Edward Almond Walker The Leyland May Festival Queen who ' died' and married 24 Sylvia Thompson the Undertaker 30 Leyland Lane Methodist Church Closure Mattie Richardson 31 The Lost Orchards of Farington Joan Langford Extract from Leyland St Andrew' s Parish Magazine - 37 Shirley Robson March 1906 38 Crowned in a Yard Margaret Nicholas 39 The OldeTripe Shop at 38 Towngate, Leyland Shirley Robson 50 Well FancyThat Joan Langford 47 Pot-pourri Derek Wilkins 50 Well FancyThat Joan Langford Editorial 4 Lailand Chronicle No. -

Lancashire Advanced Manufacturing and Energy Cluster Brochure

Lancashire Advanced Manufacturing and Energy Cluster The Lancashire Enterprise Partnership (LEP) has been successful in securing Enterprise Zone (EZ) status for four sites across Lancashire; the largest number of Enterprise Zones awarded to a single Local Enterprise Partnership. These sites are at Samlesbury and Warton, adjacent to BAE Systems’ operations, Blackpool Airport and Hillhouse near Fleetwood. The four EZ sites have a strong and complementary industrial focus, building on Lancashire’s national and international strengths in the aerospace, advanced engineering and manufacturing, energy and chemicals industries; and collectively will help to create over 10,000 highly productive high value jobs and an economic and investor offer of truly Northern Powerhouse significance. Four key development sites have combined into one dynamic, world-class and overarching investment destination – the Lancashire Advanced Manufacturing and Energy Cluster. Sector focus: Sector focus: Sector focus: Sector focus: Advanced Manufacturing Aviation, Energy & Energy, Chemicals & Advanced Manufacturing & Engineering Advanced Manufacturing Polymers & Engineering The UK’s newest Blackpool Airport offers Hillhouse Technology The site offers opportunities Advanced Engineering bespoke aviation solutions Enterprise Zone provides for companies to locate and Manufacturing site and other commercial airside facilities for the chemical alongside BAE Systems’ immediately adjacent to a activities including helicopter sector on an existing, Military Air and Information manufacturing centre for BAE and private flights, and the internationally recognised Division, which has Systems, one of the world’s flagship Lancashire Energy HQ business park. developed some of the most most advanced, technology- will act as a training base for advanced engineering led defence, aerospace the national energy sector. and manufacturing capability and security solutions anywhere in the world. -

THE FORBES REINVENTION and RESILIENCE Top 50 Welcome to the First Forbes Reinvention and Resilience Top 50 Report

THE FORBES REINVENTION AND RESILIENCE Top 50 Welcome to the first Forbes Reinvention and Resilience Top 50 Report What makes a good leader? From politicians to renowned business people – everyone has their own idea of what a great leader looks like. Apple co-founder, Steve Jobs, once said that ‘innovation distinguishes between a leader and a follower’, while author, John Maxwell, believes ‘the pessimist complains about the wind. The optimist expects it to change. The leader adjusts the sails.’ Right now, both of these descriptions resonate and are relevant for leaders of today. It’s the subject of innovation that led to our inaugural Reinvention and Resilience Top 50, and it’s the ability of business leaders in the North West to tackle whatever is thrown at them – and have the flexibility and mindset to change course for the benefit of their business – that makes this list so impressive. One thing is clear: a successful leader is one who has the ability to step outside their comfort zone and adopt new ways of working that meet the needs of the business there and then. That’s exactly what the leaders of these 50 companies have done. The region has responded with the passion, personality and determination that sets us apart from others. Each company, and every leader, has shown innovation in one way or another; each has adjusted the business’ sails to navigate one of the toughest trading periods we’ve ever seen. We hope this list serves as a blueprint for future leaders and an example of the reinvention and resilience that exists across the North West. -

Preston & Chorley

to Lancaster 40,41 Lan and Garstang e AB4C to Longridge CDEFon 1 to Longridge Urt D’ Ea ay Grimsargh ay stw E Main bus routes in & around ay Eastw A astway torw 6 M55 Mo 4C T C M d 4 a a e G 6 b Lan 40 o l a R e ot Preston & Chorley gh wo C Li tfo r d ASDA y Higher a o 4 s 41 ro B d M t o 1 a D to n r r w 1 Bartle e r 1 n a e g i y L o a a v g n L L n e e d e t R i h James Hall & Co r a o o fo c 4C g t J a y n h a ig C d o L L 4 n Sherwood L a W C i 4C B n c o e l e ne u n a L e w Preston D Junction 31a Be Tan a r y ll te Ingol y . a W Crematorium G Royal Preston rt a D W on o l ds y Golf Course l a n 1 s n sa r Hospital r u g n n E s y i Cottam B o e v t a L l H e l a n B s a k S L l e B e u n a Sharoe e B Wa c h t l g m a w a C l 4 s r n l a o Red o t R r R Green To e d. -

143 Hoghton Lane, Preston, Pr5 0Je (Pr 5 0Je)

Customer Profile Report for OLD OAK INN, HOGHTON (Punch Outlet Number: 203060) 143 HOGHTON LANE, PRESTON, PR5 0JE (PR 5 0JE) Copyright Experian Ltd, HERE 2015. Ordnance Survey © Crown copyright 2015 Age Data Table Count: Index: 0 - 0.5 0 - 1.5 0 - 3.0 0 - 5.0 15 Min 0 - 0.5 0 - 1.5 0 - 3.0 0 - 5.0 15 Min Miles Miles Miles Miles Drivetime Miles Miles Miles Miles Drivetime 0-15 277 1,114 11,046 47,594 45,144 68 83 108 103 105 16-17 34 146 1,341 5,867 5,448 68 88 106 102 102 18-24 144 463 4,279 27,698 25,857 73 72 87 124 125 25-34 166 698 7,323 35,540 32,016 56 72 98 105 102 35-44 214 833 6,808 30,550 28,830 78 92 98 98 99 45-54 360 1,183 7,955 34,065 31,866 117 117 103 97 98 55-64 348 1,005 6,150 26,020 24,372 142 125 100 93 94 65+ 625 1,681 9,599 39,182 35,561 160 131 98 88 86 Population estimate 2015 2,168 7,123 54,501 246,516 229,094 100 100 100 100 100 Ethnicity - Census 2011 Count: %: 0 - 0.5 0 - 1.5 0 - 3.0 0 - 5.0 15 Min 0 - 0.5 0 - 1.5 0 - 3.0 0 - 5.0 15 Min Miles Miles Miles Miles Drivetime Miles Miles Miles Miles Drivetime White 2,136 6,916 48,825 202,948 190,563 99% 98% 90% 84% 85% Mixed / Multiple Ethnic Groups 24 75 892 4,216 3,767 1% 1% 2% 2% 2% Asian / Asian British 7 54 3,921 29,987 26,039 0% 1% 7% 12% 12% Black / African / Caribbean / Black British 0 4 433 1,923 1,879 0% 0% 1% 1% 1% Other Ethnic Group 0 3 169 1,612 1,557 0% 0% 0% 1% 1% All People (Ethnic Group) 2,167 7,052 54,240 240,686 223,805 100 100 100 100 100 Copyright © 2016 Experian Limited.