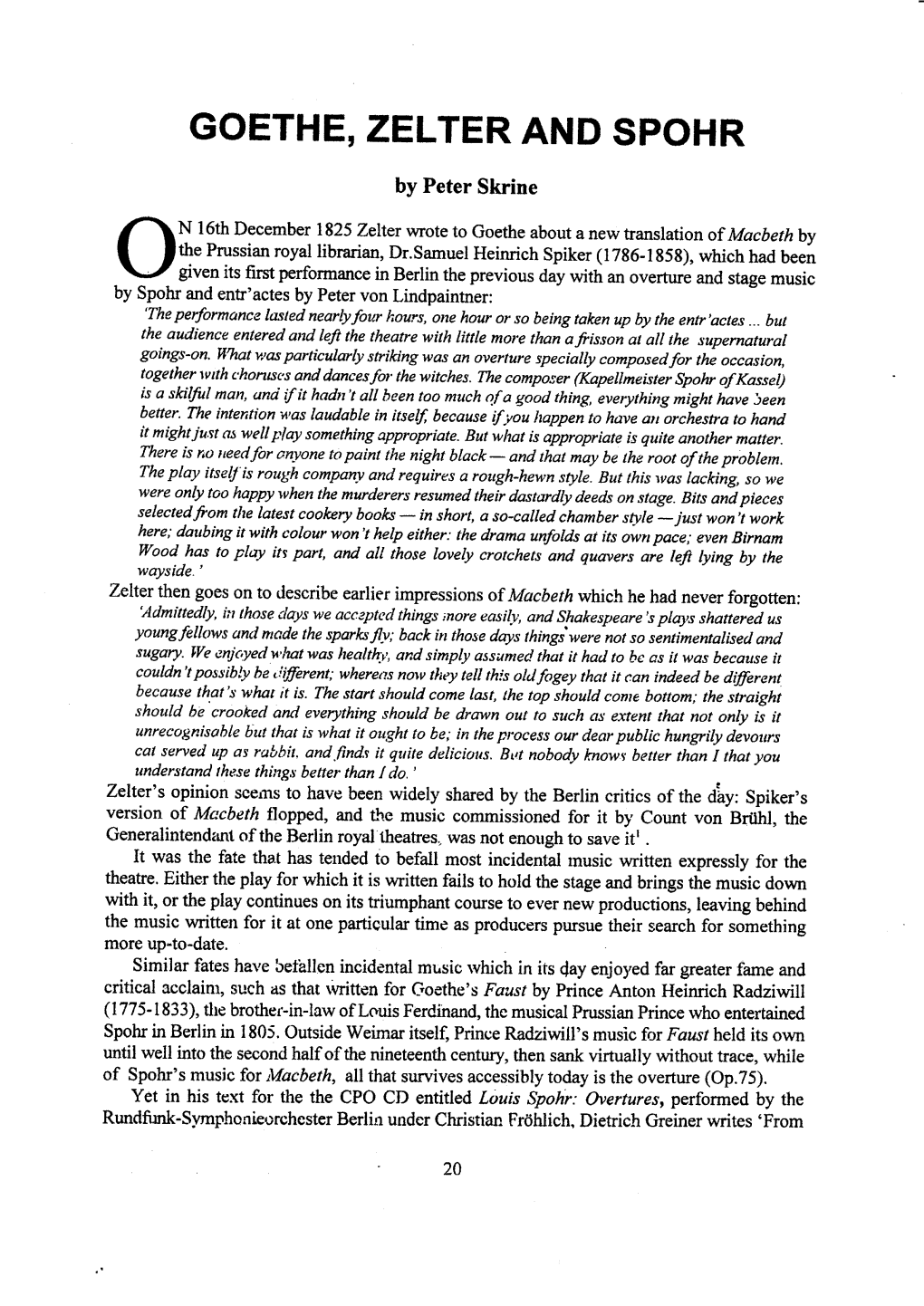

Goethe, Zelter and Spohr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Halle, the City of Music a Journey Through the History of Music

HALLE, THE CITY OF MUSIC A JOURNEY THROUGH THE HISTORY OF MUSIC 8 WC 9 Wardrobe Ticket office Tour 1 2 7 6 5 4 3 EXHIBITION IN WILHELM FRIEDEMANN BACH HOUSE Wilhelm Friedemann Bach House at Grosse Klausstrasse 12 is one of the most important Renaissance houses in the city of Halle and was formerly the place of residence of Johann Sebastian Bach’s eldest son. An extension built in 1835 houses on its first floor an exhibition which is well worth a visit: “Halle, the City of Music”. 1 Halle, the City of Music 5 Johann Friedrich Reichardt and Carl Loewe Halle has a rich musical history, traces of which are still Johann Friedrich Reichardt (1752–1814) is known as a partially visible today. Minnesingers and wandering musicographer, composer and the publisher of numerous musicians visited Giebichenstein Castle back in the lieder. He moved to Giebichenstein near Halle in 1794. Middle Ages. The Moritzburg and later the Neue On his estate, which was viewed as the centre of Residenz court under Cardinal Albrecht von Brandenburg Romanticism, he received numerous famous figures reached its heyday during the Renaissance. The city’s including Ludwig Tieck, Clemens Brentano, Novalis, three ancient churches – Marktkirche, St. Ulrich and St. Joseph von Eichendorff and Johann Wolfgang von Moritz – have always played an important role in Goethe. He organised musical performances at his home musical culture. Germany’s oldest boys’ choir, the in which his musically gifted daughters and the young Stadtsingechor, sang here. With the founding of Halle Carl Loewe took part. University in 1694, the middle classes began to develop Carl Loewe (1796–1869), born in Löbejün, spent his and with them, a middle-class musical culture. -

THE VIRTUOSO UNDER SUBJECTION: HOW GERMAN IDEALISM SHAPED the CRITICAL RECEPTION of INSTRUMENTAL VIRTUOSITY in EUROPE, C. 1815 A

THE VIRTUOSO UNDER SUBJECTION: HOW GERMAN IDEALISM SHAPED THE CRITICAL RECEPTION OF INSTRUMENTAL VIRTUOSITY IN EUROPE, c. 1815–1850 A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Zarko Cvejic August 2011 © 2011 Zarko Cvejic THE VIRTUOSO UNDER SUBJECTION: HOW GERMAN IDEALISM SHAPED THE CRITICAL RECEPTION OF INSTRUMENTAL VIRTUOSITY IN EUROPE, c. 1815–1850 Zarko Cvejic, Ph. D. Cornell University 2011 The purpose of this dissertation is to offer a novel reading of the steady decline that instrumental virtuosity underwent in its critical reception between c. 1815 and c. 1850, represented here by a selection of the most influential music periodicals edited in Europe at that time. In contemporary philosophy, the same period saw, on the one hand, the reconceptualization of music (especially of instrumental music) from ―pleasant nonsense‖ (Sulzer) and a merely ―agreeable art‖ (Kant) into the ―most romantic of the arts‖ (E. T. A. Hoffmann), a radically disembodied, aesthetically autonomous, and transcendent art and on the other, the growing suspicion about the tenability of the free subject of the Enlightenment. This dissertation‘s main claim is that those three developments did not merely coincide but, rather, that the changes in the aesthetics of music and the philosophy of subjectivity around 1800 made a deep impact on the contemporary critical reception of instrumental virtuosity. More precisely, it seems that instrumental virtuosity was increasingly regarded with suspicion because it was deemed incompatible with, and even threatening to, the new philosophic conception of music and via it, to the increasingly beleaguered notion of subjective freedom that music thus reconceived was meant to symbolize. -

Programa Del Otoño Musical Soriano 2016

PRESIDENCIA DE HONOR S.A.R LA INFANTA Dª MARGARITA DE BORBÓN Y EL EXCMO. SR. D. CARLOS ZURITA. DUQUES DE SORIA Director Festival: Jose Manuel Aceña Notas al programa: Sonia Gonzalo Delgado Diseño y maquetación: Estudioayllón Impresión: Imprenta Provincial de Soria Organiza: Plaza Mayor s/n. 42071· SORIA Tel: 975 23 41 14 / 975 23 28 69 [email protected] www.soria.es/festivalmusical Dep. Leg: SO - 55/2016 Saluda del Alcalde Estimados amigos, estimadas amigas, Gracias por compartir un año más esta cita con la música y la cultura en nuestra Ciudad que es el Otoño Musical Soriano. Como podrán com- probar en este programa de mano, la vigesimocuarta edición de nuestro Festival refleja su carácter accesible, atractivo, completo y ambicioso que reedita la conexión mágica con ustedes, el público, verdadero artífice de que el Otoño Musical Soriano se supere año a año, convirtiéndose en uno de los principales festivales musicales a nivel europeo. Así lo atestigua el galardón “EFFE Label”, recibido el pasado año desde la Asociación Eu- ropea de Festivales como marca de calidad del Otoño Musical Soriano. A punto de celebrar 25 años de historia desde que el trabajo y el cariño del Maestro Odón Alonso hacia Soria alumbrara esta cita por primera vez, las máximas de compromiso con el talento artístico y la excelen- cia internacional están presentes desde la inauguración a la clausura gracias a la labor de su Director, el Maestro José Manuel Aceña, quien ha sabido comprender y transmitir el legado del Maestro Alonso. Sirvan estas líneas para reconocer una vez más su trabajo al frente del Festival. -

![[STENDHAL]. — Joachim Rossini , Von MARIA OTTINGUER, Leipzig 1852](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2533/stendhal-joachim-rossini-von-maria-ottinguer-leipzig-1852-472533.webp)

[STENDHAL]. — Joachim Rossini , Von MARIA OTTINGUER, Leipzig 1852

REVUE DES DEUX MONDES , 15th May 1854, pp. 731-757. Vie de Rossini , par M. BEYLE [STENDHAL]. — Joachim Rossini , von MARIA OTTINGUER, Leipzig 1852. SECONDE PÉRIODE ITALIENNE. — D’OTELLO A SEMIRAMIDE. IV. — CENERENTOLA ET CENDRILLON. — UN PAMPHLET DE WEBER. — LA GAZZA LADRA. — MOSÈ [MOSÈ IN EGITTO]. On sait que Rossini avait exigé cinq cents ducats pour prix de la partition d’Otello (1). Quel ne fut point l’étonnement du maestro lorsque le lendemain de la première représentation de son ouvrage il reçut du secrétaire de Barbaja [Barbaia] une lettre qui l’avisait qu’on venait de mettre à sa disposition le double de cette somme! Rossini courut aussitôt chez la Colbrand [Colbran], qui, pour première preuve de son amour, lui demanda ce jour-là de quitter Naples à l’instant même. — Barbaja [Barbaia] nous observe, ajouta-t-elle, et commence à s’apercevoir que vous m’êtes moins indifférent que je ne voudrais le lui faire croire ; les mauvaises langues chuchotent : il est donc grand temps de détourner les soupçons et de nous séparer. Rossini prit la chose en philosophe, et se rappelant à cette occasion que le directeur du théâtre Valle le tourmentait pour avoir un opéra, il partit pour Rome, où d’ailleurs il ne fit cette fois qu’une rapide apparition. Composer la Cenerentola fut pour lui l’affaire de dix-huit jours, et le public romain, qui d’abord avait montré de l’hésitation à l’endroit de la musique du Barbier [Il Barbiere di Siviglia ], goûta sans réserve, dès la première épreuve, cet opéra, d’une gaieté plus vivante, plus // 732 // ronde, plus communicative, mais aussi trop dépourvue de cet idéal que Cimarosa mêle à ses plus franches bouffonneries. -

Orchestral Conducting in the Nineteenth Century," Edited by Roberto Illiano and Michela Niccolai Clive Brown University of Leeds

Performance Practice Review Volume 21 | Number 1 Article 2 "Orchestral Conducting in the Nineteenth Century," edited by Roberto Illiano and Michela Niccolai Clive Brown University of Leeds Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/ppr Part of the Music Performance Commons, and the Other Music Commons Brown, Clive (2016) ""Orchestral Conducting in the Nineteenth Century," edited by Roberto Illiano and Michela Niccolai," Performance Practice Review: Vol. 21: No. 1, Article 2. DOI: 10.5642/perfpr.201621.01.02 Available at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/ppr/vol21/iss1/2 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Claremont at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Performance Practice Review by an authorized editor of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Book review: Illiano, R., M. Niccolai, eds. Orchestral Conducting in the Nineteenth Century. Turnhout: Brepols, 2014. ISBN: 9782503552477. Clive Brown Although the title of this book may suggest a comprehensive study of nineteenth- century conducting, it in fact contains a collection of eighteen essays by different au- thors, offering a series of highlights rather than a broad and connected picture. The collection arises from an international conference in La Spezia, Italy in 2011, one of a series of enterprising and stimulating annual conferences focusing on aspects of nineteenth-century music that has been supported by the Centro Studi Opera Omnia Luigi Boccherini (Lucca), in this case in collaboration with the Società di Concerti della Spezia and the Palazzetto Bru Zane Centre de musique romantique française (Venice). -

Inhalt / Contents

Inhalt / Contents Grußwort / Greeting........................................... 7 II - Psalmvertonungen und Gebete / Vorwort / Preface................................................ 9 Psalm Settings and Prayers.............. 49 Ganz Europa im Fokus • Die Auswahl als repräsentativer Zeitspiegel und abgestimmt auf die heutige Praxis • Dominus regit m e.................................................. 50 Zur Gliederung der Chorstücke - Ein reichhaltiges Chorreper Carl Nielsen (1865-1931) toire • A cappella oder mit Begleitung? • Zur Interpretation - W ie der Hirsch schreiet / As the Hart Panteth.......... 58 Geistliche Chormusik im „langen 19. Jahrhundert" • Zur Heinrich Bellermann (1832-1903) Verwendung des Romantik-Begriffs im Titel des Chorbuchs • Editorische Anmerkungen - Zu den verwendeten Bibel Sicut cervus........................................................... 64 versionen • Hilfestellungen für die Probenarbeit Charles Gounod (1818-1893) All of Europe in the limelight • The selection as a represen Kot po mrzli studencini / As the Thirsting Hart Pants.. 67 tative reflection of the times, yet in tune with modern Hugolin Sattner (1851-1934) practice - The organisation of the choral pieces • A rich Sende dein Licht (Kanon) / and extensive choral repertoire • A cappella or with accom Send Out Thy Light (Canon)............................... 68 paniment? • Concerning performance • Sacred choral music Friedrich Schneider (1786-1853) in the "long nineteenth century" • On the use of the term "Romantik" in the title of this choir -

Carl Loewe's "Gregor Auf Dem Stein": a Precursor to Late German Romanticism

Carl Loewe's "Gregor auf dem Stein": A Precursor to Late German Romanticism Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Witkowski, Brian Charles Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 04/10/2021 03:11:55 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/217070 CARL LOEWE'S “GREGOR AUF DEM STEIN”: A PRECURSOR TO LATE GERMAN ROMANTICISM by Brian Charles Witkowski _____________________ Copyright © Brian Charles Witkowski 2011 A Document Submitted to the Faculty of the SCHOOL OF MUSIC In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2011 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Document Committee, we certify that we have read the document prepared by Brian Charles Witkowski entitled Carl Loewe's “Gregor auf dem Stein”: A Precursor to Late German Romanticism and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the document requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts ________________________________________________ Date: 11/14/11 Charles Roe ________________________________________________ Date: 11/14/11 Faye Robinson ________________________________________________ Date: 11/14/11 Kristin Dauphinais Final approval and acceptance of this document is contingent upon the candidate’s submission of the final copies of the document to the Graduate College. I hereby certify that I have read this document prepared under my direction and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the document requirement. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly fiom the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter fitce, while others may be fi-om any type o f computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely aJEfect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing fi’om left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations tq)pearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI A Bell & Howell hifinmatioa Con^any 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor MI 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 THE CELLO AND PIANO SONATAS OF EMILIE MAYER (1821-1883) DOCUMENT Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts in the School of Music of The Ohio State University By Marie-Aline Cadieux, M.M. -

Bach's St. Matthew Passion

“It was an actor and a Jew who restored this great Christian work to the people.” - Felix Mendelssohn Bach’s Great Passion: A Reintroduction In 1829, a young Jewish musician (already on the path to create his own compositional legacy) reintroduced Berlin to Johann Sebastian Bach’s masterpiece, the Passio Domini Nostri Jesu Christi secundum Evangelistam Matthæum, also known as the Matthäus-Passion, The Passion According to St. Matthew, or simply, The St. Matthew Passion. Ten years earlier, that musician - Felix Mendelssohn - began taking composition lessons from the director of the Berlin Singakademie, Carl Friedrich Zelter. Through this relationship, Mendelssohn would learn to love the music of Bach. Zelter himself had conducted quiet performances of a handful of the German master’s choral works at the Singakademie: a motet here, some cantata movements there. Even some of the choruses from the Passion were read at his rooms at the Singakademie. He was, however, of the opinion that these larger works were not suitable for public performance in their entirety. Still, running against the predominant tastes of the day, that Bach’s music was, according to one early 20th-century scholar, as “dry as a lesson in arithmetic,” the self-taught Zelter (he was a mason by trade), infused his love of Bach in his favorite student. In 1820, Mendelssohn joined the Singakademie as a choral singer and accompanist. His father, Abraham, had given a collection of Bach scores to its library and had been an earlier supporter of the Berlin musical institution. Earlier, Felix’s grand-aunt, Sarah Levy (who studied with J. -

Classic Choices April 6 - 12

CLASSIC CHOICES APRIL 6 - 12 PLAY DATE : Sun, 04/12/2020 6:07 AM Antonio Vivaldi Violin Concerto No. 3 6:15 AM Georg Christoph Wagenseil Concerto for Harp, Two Violins and Cello 6:31 AM Guillaume de Machaut De toutes flours (Of all flowers) 6:39 AM Jean-Philippe Rameau Gavotte and 6 Doubles 6:47 AM Ludwig Van Beethoven Consecration of the House Overture 7:07 AM Louis-Nicolas Clerambault Trio Sonata 7:18 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Divertimento for Winds 7:31 AM John Hebden Concerto No. 2 7:40 AM Jan Vaclav Vorisek Sonata quasi una fantasia 8:07 AM Alessandro Marcello Oboe Concerto 8:19 AM Franz Joseph Haydn Symphony No. 70 8:38 AM Darius Milhaud Carnaval D'Aix Op 83b 9:11 AM Richard Strauss Der Rosenkavalier: Concert Suite 9:34 AM Max Reger Flute Serenade 9:55 AM Harold Arlen Last Night When We Were Young 10:08 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Exsultate, Jubilate (Motet) 10:25 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Symphony No. 3 10:35 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Piano Concerto No. 10 (for two pianos) 11:02 AM Johannes Brahms Symphony No. 4 11:47 AM William Lawes Fantasia Suite No. 2 12:08 PM John Ireland Rhapsody 12:17 PM Heitor Villa-Lobos Amazonas (Symphonic Poem) 12:30 PM Allen Vizzutti Celebration 12:41 PM Johann Strauss, Jr. Traumbild I, symphonic poem 12:55 PM Nino Rota Romeo & Juliet and La Strada Love 12:59 PM Max Bruch Symphony No. 1 1:29 PM Pr. Louis Ferdinand of Prussia Octet 2:08 PM Muzio Clementi Symphony No. -

German Virtuosity

CONCERT PROGRAM III: German Virtuosity July 20 and 22 PROGRAM OVERVIEW Concert Program III continues the festival’s journey from the Classical period Thursday, July 20 into the nineteenth century. The program offers Beethoven’s final violin 7:30 p.m., Stent Family Hall, Menlo School sonata as its point of departure into the new era—following a nod to the French Saturday, July 22 virtuoso Pierre Rode, another of Viotti’s disciples and the sonata’s dedicatee. In 6:00 p.m., The Center for Performing Arts at Menlo-Atherton the generation following Beethoven, Louis Spohr would become a standard- bearer for the German violin tradition, introducing expressive innovations SPECIAL THANKS such as those heard in his Double String Quartet that gave Romanticism its Music@Menlo dedicates these performances to the following individuals and musical soul. The program continues with music by Ferdinand David, Spohr’s organizations with gratitude for their generous support: prize pupil and muse to the German tradition’s most brilliant medium, Felix July 20: The William and Flora Hewlett Foundation Mendelssohn, whose Opus 3 Piano Quartet closes the program. July 22: Alan and Corinne Barkin PIERRE RODE (1774–1830) FERDINAND DAVID (1810–1873) Caprice no. 3 in G Major from Vingt-quatre caprices en forme d’études for Solo Caprice in c minor from Six Caprices for Solo Violin, op. 9, no. 3 (1839) CONCERT PROGRAMS CONCERT Violin (ca. 1815) Sean Lee, violin Arnaud Sussmann, violin FELIX MENDELSSOHN (1809–1847) LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN (1770–1827) Piano Quartet no. 3 in b minor, op. 3 (1825) Violin Sonata no. -

Ghost Trio, As Ludwig Van Beethoven’S Op

Reiselust Werke von Beethoven, Spohr und Mendelssohn Eldering Ensemble Reiselust Werke von Beethoven, Spohr und Mendelssohn Eldering Ensemble Simon Monger Violine Jeanette Gier Violoncello Sandra Urba Klavier Ludwig van Beethoven (1770–1827) Trio für Klavier, Violine und Violoncello Nr. 5 D-Dur op. 70 Nr. 1 Geistertrio (1808) 01 I. Allegro vivace e con brio .......................................(09'57) 02 II. Largo assai ed espressivo ......................................(10'04) 03 III. Presto .......................................................(07'56) Louis Spohr (1784–1859) Duetto für Pianoforte und Violine op. 96 Reisesonate Nachklänge einer Reise nach Dresden und in die Sächsische Schweiz (1836) 04 I. Reiselust: Allegro ..............................................(08'11) 05 II. Reise: Scherzo ................................................(06'01) 06 III. Katholische Kirche: Andante maestoso – Larghetto ............(06'00) 07 IV. Sächsische Schweiz: Rondo Allegretto .........................(05'59) Weltersteinspielung der neuen Urtextausgabe (Uta Pape), Edition Dohr Köln Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy (1809–1847) Trio für Violine, Violoncello und Klavier Nr. 2 c-Moll op. 66 (1845) 08 I. Allegro energico e con fuoco ....................................(10'14) 09 II. Andante espressivo ...........................................(07'02) 10 III. Scherzo. Molto allegro quasi presto ...........................(03'28) 11 IV. Finale. Allegro appassionato ..................................(07'15) Gesamtspielzeit ........................................................(82'15)