Regeneration Through Heritage:Understanding Thedevelopmentpotentialofhistoriceuropean Arsenals

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bus Services from Lewisham

River Thames to Broadwaters and Belmarsh Prison 380 Bus services from Lewisham Plumstead Bus Garage Woolwich for Woolwich Arsenal Station 180 122 to Abbey Wood, Thamesmead East 54 and Belvedere Moorgate 21 47 N 108 Finsbury Square Industrial Area Shoreditch Stratford Bus Station Charlton Anchor & Hope Lane Woolwich Bank W E Dockyard Bow Bromley High Street Liverpool Street 436 Paddington East Greenwich Poplar North Greenwich Vanbrugh Hill Blackwall Tunnel Woolwich S Bromley-by-Bow Station Eastcombe Charlton Common Monument Avenue Village Edgware Road Trafalgar Road Westcombe Park Sussex Gardens River Thames Maze Hill Blackheath London Bridge Rotherhithe Street Royal Standard Blackheath Shooters Hill Marble Arch Pepys Estate Sun-in-the-Sands Police Station for London Dungeon Holiday Inn Grove Street Creek Road Creek Road Rose Creekside Norman Road Rotherhithe Bruford Trafalgar Estate Hyde Park Corner Station Surrey College Bermondsey 199 Quays Evelyn Greenwich Queens House Station Street Greenwich Church Street for Maritime Museum Shooters Hill Road 185 Victoria for Cutty Sark and Greenwich Stratheden Road Maritime Museum Prince Charles Road Cutty Sark Maze Hill Tower 225 Rotherhithe Canada Deptford Shooters Hill Pimlico Jamaica Road Deptford Prince of Wales Road Station Bridge Road Water Sanford Street High Street Greenwich Post Office Prince Charles Road Bull Druid Street Church Street St. Germans Place Creek Road Creek Road The Clarendon Hotel Greenwich Welling Borough Station Pagnell Street Station Montpelier Row Fordham Park Vauxhall -

Greenwich Waterfront Transit

Greenwich Waterfront Transit Summary Report This report has been produced by TfL Integration Further copies may be obtained from: Tf L Integration, Windsor House, 42–50 Victoria Street, London SW1H 0TL Telephone 020 7941 4094 July 2001 GREENWICH WATERFRONT TRANSIT • SUMMARY REPORT Foreword In 1997, following a series of strategic studies into the potential for intermediate modes in different parts of outer London, London Transport (LT) commenced a detailed assessment under the title “Greenwich Waterfront Transit” of a potential scheme along the south bank of the Thames between Greenwich Town Centre and Thamesmead then on to Abbey Wood. In July 2000, LT’s planning functions were incorporated into Transport for London (TfL). A major factor in deciding to carry out a detailed feasibility study for Waterfront Transit has been the commitment shown by Greenwich and Bexley Councils to assist in the development of the project and their willingness to consider the principle of road space re-allocation in favour of public transport. This support, as well as that of other bodies such as SELTRANS, Greenwich Development Agency,Woolwich Development Agency and the Thames Gateway London Partnership, is acknowledged by TfL. The ongoing support of these bodies will be crucial if the proposals are to proceed. A major objective of this exercise has been to identify the traffic management measures required to achieve segregation and high priority over other traffic to encourage modal shift towards public transport, particularly from the private car. It is TfL’s view,supported by the studies undertaken, that the securing of this segregation and priority would be critical in determining the success of Waterfront Transit. -

Imperial War Museum Annual Report and Accounts 2019-20

Imperial War Museum Annual Report and Accounts 2019-20 Presented to Parliament pursuant to section 9(8) Museums and Galleries Act 1992 Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed on 7 October 2020 HC 782 © Crown copyright 2020 This publication is licensed under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/version/3. Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. This publication is available at: www.gov.uk/official-documents. Any enquiries regarding this publication should be sent to us at [email protected] ISBN 978-1-5286-1861-8 CCS0320330174 10/20 Printed on paper containing 75% recycled fibre content minimum Printed in the UK by the APS Group on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office 2 Contents Page Annual Report 1. Introduction 4 2. Strategic Objectives 5 3. Achievements and Performance 6 4. Plans for Future Periods 23 5. Financial Review 28 6. Staff Report 31 7. Environmental Sustainability Report 35 8. Reference and Administrative Details of the Charity, 42 the Trustees and Advisers 9. Remuneration Report 47 10. Statement of Trustees’ and Director-General’s Responsibilities 53 11. Governance Statement 54 The Certificate and Report of the Comptroller and Auditor 69 General to the Houses of Parliament Consolidated Statement of Financial Activities 73 The Statement of Financial Activities 74 Consolidated and Museum Balance Sheets 75 Consolidated Cash Flow Statement 76 Notes to the financial statements 77 3 1. -

20 Duke of Wellington Avenue Woolwich, London Se18 6By Commercial Unit for Sale / to Let 20 Duke of Wellington Avenue Woolwich, London Se18 6By

t 20 DUKE OF WELLINGTON AVENUE WOOLWICH, LONDON SE18 6BY COMMERCIAL UNIT FOR SALE / TO LET 20 DUKE OF WELLINGTON AVENUE WOOLWICH, LONDON SE18 6BY • Brand new B1 unit measuring c.514sqft • Located at the heart of Berkeley Homes, Royal Arsenal Riverside development • Will suit a variety of commercial uses (stpp) • For sale at offers in excess of £160,000 • To let at offers in excess of £13,000 per annum for a new FRI lease DESCRIPTION An opportunity to acquire a brand new commercial unit in the heart of Berkeley Homes landmark Royal Arsenal Riverside development. The property currently comprises a rectangular shaped unit offered in shell and core condition with capped services and will suit a variety of commercial users. LOCATION The property is situated on Duke of Wellington Parade directly across from the Royal Artillery Museum in the heart of the 88 acre mixed-use Royal Arsenal Riverside development. The unit benefits from not only from its close proximity to Woolwich Town Centre but also the commercial amenities and residential density that the wider development offers. The unit also benefits from excellent transport links in close proximity with the incoming Crossrail station 100 yards away and the Royal Arsenal DLR and National Rail stations 0.4 miles away. Acorn as our vendor’s agent have endeavoured to check the accuracy of these sales E: [email protected] particulars, but however can offer no guarantee, we therefore must advise that any W: acorncommercial.co.uk prospective purchaser employ their own experts to verify the statements contained 020 8315 5454 : @acorncommercial herein. -

The Fusilier Origins in Tower Hamlets the Tower Was the Seat of Royal

The Fusilier Origins in Tower Hamlets The Tower was the seat of Royal power, in addition to being the Sovereign’s oldest palace, it was the holding prison for competitors and threats, and the custodian of the Sovereign’s monopoly of armed force until the consolidation of the Royal Arsenal at Woolwich in 1805. As such, the Tower Hamlets’ traditional provision of its citizens as a loyal garrison to the Tower was strategically significant, as its possession and protection influenced national history. Possession of the Tower conserved a foothold in the capital, even for a sovereign who had lost control of the City or Westminster. As such, the loyalty of the Constable and his garrison throughout the medieval, Tudor and Stuart eras was critical to a sovereign’s (and from 1642 to 1660, Parliament’s) power-base. The ancient Ossulstone Hundred of the County of Middlesex was that bordering the City to the north and east. With the expansion of the City in the later Medieval period, Ossulstone was divided into four divisions; the Tower Division, also known as Tower Hamlets. The Tower Hamlets were the military jurisdiction of the Constable of the Tower, separate from the lieutenancy powers of the remainder of Middlesex. Accordingly, the Tower Hamlets were sometimes referred to as a county-within-a-county. The Constable, with the ex- officio appointment of Lord Lieutenant of Tower Hamlets, held the right to call upon citizens of the Tower Hamlets to fulfil garrison guard duty at the Tower. Early references of the unique responsibility of the Tower Hamlets during the reign of Bloody Mary show that in 1554 the Privy Council ordered Sir Richard Southwell and Sir Arthur Darcye to muster the men of the Tower Hamlets "whiche owe their service to the Towre, and to give commaundement that they may be in aredynes for the defence of the same”1. -

Greenwich Park

GREENWICH PARK CONSERVATION PLAN 2019-2029 GPR_DO_17.0 ‘Greenwich is unique - a place of pilgrimage, as increasing numbers of visitors obviously demonstrate, a place for inspiration, imagination and sheer pleasure. Majestic buildings, park, views, unseen meridian and a wealth of history form a unified whole of international importance. The maintenance and management of this great place requires sensitivity and constant care.’ ROYAL PARKS REVIEW OF GREEWNICH PARK 1995 CHAIRMAN’S FOREWORD Greenwich Park is England’s oldest enclosed public park, a Grade1 listed landscape that forms two thirds of the Maritime Greenwich World Heritage Site. The parks essential character is created by its dramatic topography juxtaposed with its grand formal landscape design. Its sense of place draws on the magnificent views of sky and river, the modern docklands panorama, the City of London and the remarkable Baroque architectural ensemble which surrounds the park and its established associations with time and space. Still in its 1433 boundaries, with an ancient deer herd and a wealth of natural and historic features Greenwich Park attracts 4.7 million visitors a year which is estimated to rise to 6 million by 2030. We recognise that its capacity as an internationally significant heritage site and a treasured local space is under threat from overuse, tree diseases and a range of infrastructural problems. I am delighted to introduce this Greenwich Park Conservation Plan, developed as part of the Greenwich Park Revealed Project. The plan has been written in a new format which we hope will reflect the importance that we place on creating robust and thoughtful plans. -

SP Location Map New 16.08.12

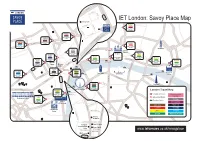

ND RA ST OW Y R S O A AV V S O Y A301 S T IET London: Savoy Place Map Savoy Hotel S A AY V Barbican Y W O AVO Y S H IL L Walking Distance C 29 mins A R T IN G E L C Holborn N LA Y P T VO EN SA M T NK Walking Distance EN BA Tottenham M M 7 mins K E Court Road N IA BA R M TO E IC IA V Oxford Circus Walking Distance R TO D ST 17 mins IC St. Paul’s OXFOR V Walking Distance Walking Distance 27 mins 22 mins ET ST The Gherkin Covent FLE Garden City Thameslink St. Paul’s R E G Cathedral Mansion E Walking Distance N Blackfriars House T 9 mins Leicester S T Square Temple Walking Distance Walking Distance Monument 15 mins UPP 28 mins Walking Distance ER THA Piccadilly MES S Circus 11 mins A4 Walking Distance T Tower Hill 10 mins Blackfriars Pier Walking Distance Leicester 32 mins ND Walking Distance RA W E Walking Distance Square Nelson’s T A G S T D L 17 mins I OW 40 mins E ER TH Column R R AMES ST B L O K O R Savoy Pier B Bankside Pier A Charing R London W A4 Cross ID H Charing Cross Embankment G T Green Park E U O Tower Millenium Pier S Tower Of Walking Distance Oxo Tower Tate Modern 7 mins T Walking Distance Festival Pier London L N Walking Distance AL D London Bridge City Pier M E 6 mins L R S E 25 mins L A3212 M OU A S G P K T R H D N W I A A A I RK R B B R S LY L T DI AL M F R E K E A M C E C A W C H I I T A P O R L T London B O T Waterloo Waterloo East C I The Shard V St. -

Gun Carriage Mews GUN CARRIAGE MEWS

Gun Carriage Mews GUN CARRIAGE MEWS A COLLECTION OF 12 BEAUTIFULLY TRANSFORMED, CONTEMPORARY APARTMENTS WITHIN A METICULOUSLY REFURBISHED GRADE II LISTED BUILDING. CONTENTS Location ..............................................................................4 Royal Borough of Greenwich ......................................6 Facilities and Outdoor Spaces ....................................8 First Rate Amenities .................................................... 10 Site Plan ............................................................................ 12 Introducing the Heritage Quarter ......................... 14 Superior Specifications .............................................. 17 Accommodation Schedule and Floor plans ...... 20 Berkeley - Designed for life ....................................... 38 1 WELCOME TO ROYAL ARSENAL RIVERSIDE Rich in history, Royal Arsenal Riverside offers unique surroundings with carefully renovated historic Grade I & II listed buildings, blending seamlessly with modern architecture. With a flourishing community and impeccable connections, this destination offers the ideal London riverside lifestyle. 3 Computer enhanced image is indicative only A UNIQUE LONDON PLACES OF INTEREST SOUTHWARK GREENWICH 1. London Bridge Station 15. Cutty Sark 2. The Shard 16. The Royal Naval College RIVERSIDE LOCATION 3. City Hall 17. National Maritime Museum 18. Royal Observatory THE CITY 19. The O2 4. Monument 20. Emirates Air Line 5. 30 St Mary Axe (The Gherkin) IN ADDITION TO THE FORTHCOMING CROSSRAIL STATION, ROYAL -

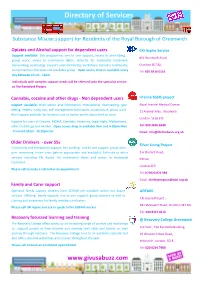

Directory of Services

Directory of Services Substance Misuse support for Residents of the Royal Borough of Greenwich Opiates and Alcohol support for dependent users CRi Aspire Service Support available: Day programme, one to one support, access to prescribing, 821 Woolwich Road, group work, access to community detox, referrals for residential treatment, key working, psychology support, peer mentoring, workshops, recovery community, Charlton SE7 8JL complimentary therapies and pre detox group. Open access drop in available every Tel: 020 8316 0116 day between 10 am - 12pm Individuals with complex support needs will be referred onto the specialist service at The Beresford Project. Cannabis, cocaine and other drugs - Non dependent users Lifeline BaSIS project Support available: Brief advice and information, motivational interviewing, goal Royal Arsenal Medical Centre setting, healthy living tips, self management techniques, acupuncture, group work. 21 Arsenal Way , Woolwich Brief support available for between one to twelve weeks dependent on need. London SE18 6TE Support for users of Cocaine, MDMA, Cannabis, Ketamine, Legal Highs, Methadrone, other Club Drugs and Alcohol. Open access drop in available 9am and 4:30pm Mon Tel: 020 3696 2640 - Fri and 9.30am - 12.30pm Sat Email: [email protected] Older Drinkers - over 55s Silver Lining Project Community and therapeutic support, key working, one to one support, group work, peer mentoring. Home visits (where appropriate and available). Referrals to other 2-6 Sherard Road, services including CRi Aspire -for community detox and access to residential Eltham, treatment. London SE9 Please call to make a referral or an appointment Tel: 079020 876 983 Email: [email protected] Family and Carer support Specialist family support workers from ADFAM are available within our Aspire ADFAM services. -

1538 the LONDON GAZETTE, 7 MARCH, 1939 Climie, Agnes, Principal Officer, H.M

1538 THE LONDON GAZETTE, 7 MARCH, 1939 Climie, Agnes, Principal Officer, H.M. Prison, Print, Louis William, Sorting Clerk and Tele- Hollo way. graphist, Birmingham. Cook, John William, Ship Fitter, H.M. Dock- Ransom, Frank Gooch, Overseer, London yard, Portsmouth. Postal Region. Cooke, James Baker, Draughtsman, Engineer- Rice, Alfred Oliver, Postman, Llanwrthwl Sub- ing Department, Royal Arsenal, Woolwich. Office, Llandrindod Wells. Dickenson, Edward Thomas William, Boiler- Richards, Edward Joseph, Supervisor, Class maker, H.M. Dockyard, Sheerness. " B," H.M. Naval Base, Portland. Diddams, William Edward, Skilled Labourer Ridley, William Watson, Postman, Sleights (Slinger), Permanent Chargeman, H.M. Station Sub-Office, Whitby. Dockyard, Chatham. Robbins, Sidney Wallace, Engine Fitter, H.M. Daniels, Florence, Assistant Supervisor, Class Dockyard, Portsmouth. II, Post Office, Dewsbury and Batley. Roberts, George, Engine Fitter, H.M. Dock- Evans, Frederick Charles, Sorting Clerk and yard, Chatham. Telegraphist, Liverpool. Robinson, Herbert Beauchamp, Patternmaker, Fletcher, Maurice Arthur, Foreman, Royal H.M. Dockyard, Portsmouth. Small Arms Factory, Enfield Lock. Schumacher, Charles George, Skilled Labourer, Ford, Dorothy, Sorting Clerk and Telegraphist, Royal Naval Armament Depot, Priddy/s Sevenoaks. Hard, Gosport. Girvan, Walter McWalter, Postman, Ayr. Sevier, George Lang, Sorting Clerk and Tele- Gow, Peter, Sorting Clerk and Telegraphist, graphist, Southampton. Perth. Shackleton, William Roger, Postman, Keighley. Haigh, Milnes, Postman, Dewsbury and Batley. Sleet, John Edward, Postman, London Postal Harris, David Edmund, Shipwright, H.M. Region. Dockyard, Portsmouth. Smith, Archibald Thomas, Riveter, H.M. Kingston, William Philip, A.B. (Yard Craft), Dockyard, Portsmouth. H.M. Dockyard, Devonport. Smith, Clara, Assistant Supervisor, Class II, Hollis, Ernest John, Acting Foreman, Research London Telecommunications Region. Department, Royal Arsenal, Woolwich. -

Re-Use and Recycle to Reduce Carbon

THERE’S NO PLACE LIKE OLD HOMES Re-use and Recycle to Reduce Carbon HERITAGE COUNTS Early morning view from Mam Tor looking down onto Castleton, Peak District, Derbyshire. © Historic England Archive 2 THERE’S NO PLACE LIKE OLD HOMES THERE’S NO PLACE LIKE OLD HOMES 3 Foreword from Sir Laurie Magnus, Chairman of Historic England I am delighted to introduce this important research that Historic England has commissioned on behalf of the Historic Environment Forum as part of its Heritage Counts series. Our sector has, for many years, been banging the drum for the historic environment to be recognised - not as a fossil of past times - but as a vital resource for the future. The research reported here demonstrates this more starkly than ever, particularly with climate change being recognised as the biggest challenge facing us today. While the threat it poses to our cherished historic environment is substantial, there are multiple ways in which historic structures can create opportunities for a more sustainable way of living. Huge amounts of carbon are locked up in existing historic buildings. Continuing to use and re-use these assets can reduce the need for new carbon-generating construction activities, thereby reducing the need for new material extraction and reducing waste production. Our built environment is a major source of greenhouse gas emissions – the third biggest in most assessments. It is therefore exciting to see that this year’s Heritage Counts research shows that we can dramatically reduce carbon in existing buildings through retrofit, refurbishment and, very importantly, through regular repair and maintenance. -

Exploring London from the Thames Events & Corporate Hire Welcome to London’S Leading Riverboat Service

UNFORGETTABLE EXPERIENCES EXPLORING LONDON FROM THE THAMES EVENTS & CORPORATE HIRE WELCOME TO LONDON’S LEADING RIVERBOAT SERVICE Thank you for organising such a great event. Prosecco was flowing, great hosts and the sun even came out WELCOME for the sunset! We’re London’s leading riverboat service, providing With a choice of 18 vessels ranging from 12 to 220 our passengers a unique way to get around the capital. capacity we offer transport for sports stars and As well as catering for sightseers and commuters, rock stars to events and concerts, wedding parties, we also offer a deluxe and highly versatile corporate company functions and even a location for filming and private hire service for those wishing to explore and photoshoot. London in comfort and style. Let us show you what we can do CONTENTSEXPLORE On Board Experience 4 Catering & Hospitality 5 Branding, Corporate & Filming 6 Cruise & Excursions 7 Our Fleet 8 Rates 16 Our Route 17 Contact Details 18 4 ONBOARDLOVE EXPERIENCE IT! Thames Clippers are the fastest and most frequent fleet on the river, with 18 vessels available for private hire. Each of our catamarans are spacious, stylish and staffed by a friendly and experienced crew. For our corporate and private clients we offer seven different sizes of vessel with the option of carrying between 12 and 222 guests. The route, length and speed of journey, stop off locations, style of catering, use of facilities on board and time of travel are flexible. This means we can deliver a vast range of events; from business meetings, presentations, networking days, conferences, celebrity parties and product launches to marriage transfers and excursions for family and friends.