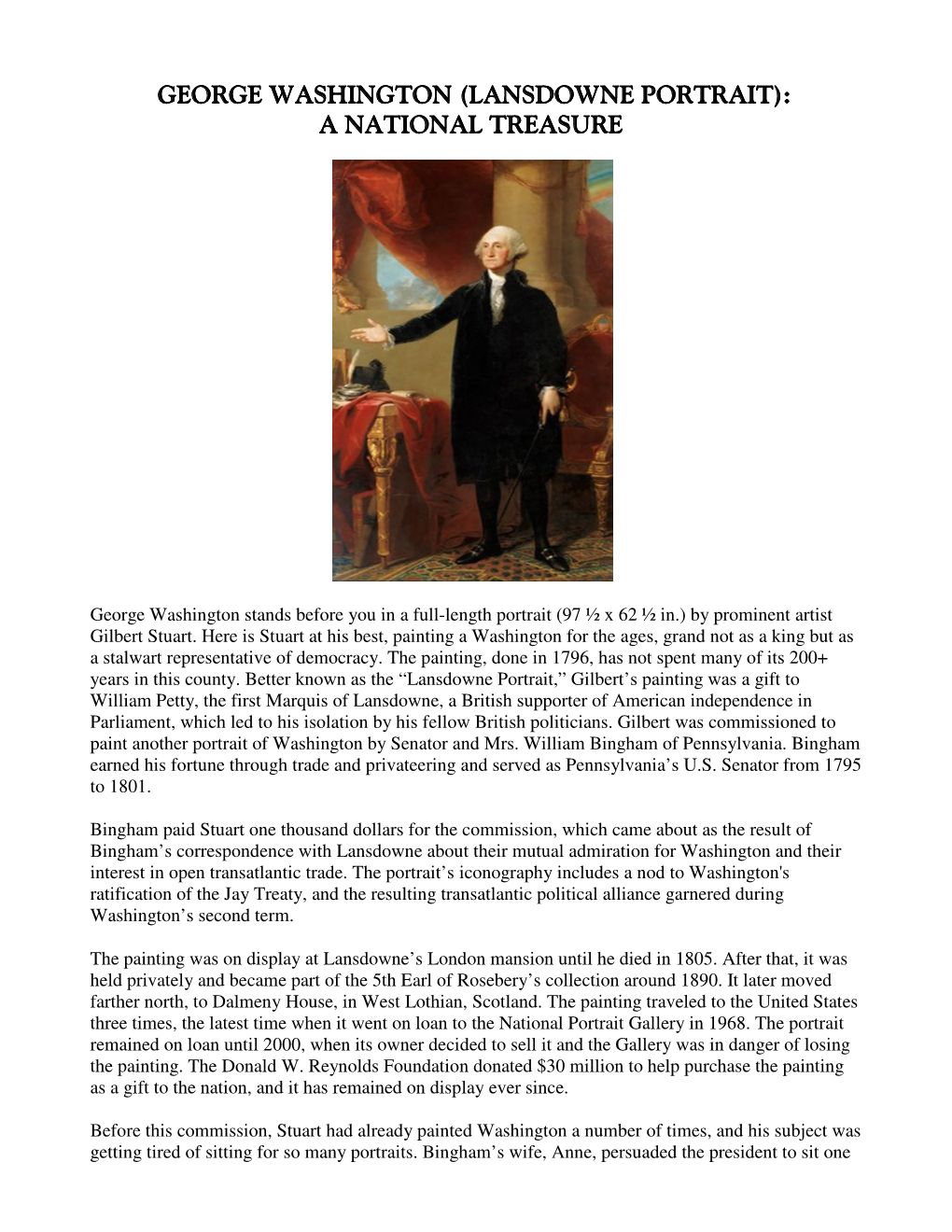

(Lansdowne Portrait): George Washington

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

D4 DEACCESSION LIST 2019-2020 FINAL for HLC Merged.Xlsx

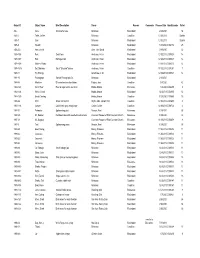

Object ID Object Name Brief Description Donor Reason Comments Process Date Box Barcode Pallet 496 Vase Ornamental vase Unknown Redundant 2/20/2020 54 1975-7 Table, Coffee Unknown Condition 12/12/2019 Stables 1976-7 Saw Unknown Redundant 12/12/2019 Stables 1976-9 Wrench Unknown Redundant 1/28/2020 C002172 25 1978-5-3 Fan, Electric Baer, John David Redundant 2/19/2020 52 1978-10-5 Fork Small form Anderson, Helen Redundant 12/12/2019 C001523 14 1978-10-7 Fork Barbeque fork Anderson, Helen Redundant 12/12/2019 C001523 14 1978-10-9 Masher, Potato Anderson, Helen Redundant 12/12/2019 C001523 14 1978-10-16 Set, Dishware Set of "Bluebird" dishes Anderson, Helen Condition 11/12/2019 C001351 7 1978-11 Pin, Rolling Grantham, C. W. Redundant 12/12/2019 C001523 14 1981-10 Phonograph Sonora Phonograph Co. Unknown Redundant 2/11/2020 1984-4-6 Medicine Dr's wooden box of antidotes Fugina, Jean Condition 2/4/2020 42 1984-12-3 Sack, Flour Flour & sugar sacks, not local Hobbs, Marian Relevance 1/2/2020 C002250 9 1984-12-8 Writer, Check Hobbs, Marian Redundant 12/3/2019 C002995 12 1984-12-9 Book, Coloring Hobbs, Marian Condition 1/23/2020 C001050 15 1985-6-2 Shirt Arrow men's shirt Wythe, Mrs. Joseph Hills Condition 12/18/2019 C003605 4 1985-11-6 Jumper Calvin Klein gray wool jumper Castro, Carrie Condition 12/18/2019 C001724 4 1987-3-2 Perimeter Opthamology tool Benson, Neal Relevance 1/29/2020 36 1987-4-5 Kit, Medical Cardboard box with assorted medical tools Covenant Women of First Covenant Church Relevance 1/29/2020 32 1987-4-8 Kit, Surgical Covenant -

Key Facts About Kenmore, Ferry Farm, and the Washington and Lewis Families

Key Facts about Kenmore, Ferry Farm, and the Washington and Lewis families. The George Washington Foundation The Foundation owns and operates Ferry Farm and Historic Kenmore. The Foundation is a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization. The Foundation (then known as the Kenmore Association) was formed in 1922 in order to purchase Kenmore. The Foundation purchased Ferry Farm in 1996. Historic Kenmore Kenmore was built by Fielding Lewis and his wife, Betty Washington Lewis (George Washington’s sister). Fielding Lewis was a wealthy merchant, planter, and prominent member of the gentry in Fredericksburg. Construction of Kenmore started in 1769 and the family moved into their new home in the fall of 1775. Fielding Lewis' Fredericksburg plantation was once 1,270 acres in size. Today, the house sits on just one city block (approximately 3 acres). Kenmore is noted for its eighteenth-century, decorative plasterwork ceilings, created by a craftsman identified only as "The Stucco Man." In Fielding Lewis' time, the major crops on the plantation were corn and wheat. Fielding was not a major tobacco producer. When Fielding died in 1781, the property was willed to Fielding's first-born son, John. Betty remained on the plantation for another 14 years. The name "Kenmore" was first used by Samuel Gordon, who purchased the house and 200 acres in 1819. Kenmore was directly in the line of fire between opposing forces in the Battle of Fredericksburg in 1862 during the Civil War and took at least seven cannonball hits. Kenmore was used as a field hospital for approximately three weeks during the Civil War Battle of the Wilderness in 1864. -

132 Portraits by Gilbert Stuart. in 1914

132 Portraits by Gilbert Stuart. PORTRAITS BY GILBERT STUART NOT INCLUDED IN PREVIOUS CATALOGUES OF HIS WORKS. BY MANTLE FIELDING. In 1914 the '' Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography" published a list of portraits painted by Gilbert Stuart, not mentioned in the "Life and Works of Gilbert Stuart" by George C. Mason. In 1920 this was followed in the same periodical by "Addenda and Corrections" to the first list, in all adding about one hundred and eighty portraits to the original pub- lication. This was followed in 1926 by the descriptive cata- logue of Stuart's work by the late Laurence Park, which noted many additions that up to that time had eluded the collectors' notice. In the last two years there have come to America a number of Stuart por- traits which were painted in England and Ireland and practically unknown here before. As a rule they differ in treatment and technique from his work in America and are reminiscent more or less of the English school. Many of these portraits lack some of the freedom and spirit of his American work having the more careful finish and texture of Eomney and Gainsborough. These paintings of Gil- bert Stuart made during his residence in England and Ireland possess a great charm like all the work of this talented painter and are now being much sought after by collectors in this country. No catalogue of the works of an early painter, how- ever, can be called complete or infallible and in the case of Gilbert Stuart there seems to be good reason to believe that there are still many of his portraits in Portraits by Gilbert Stuart. -

Woodlawn Historic District in Fairfax Co VA

a l i i Woodlawn was a gift from George Washington In 1846, a group of northern Quakers purchased n a i r g to his step-granddaughter, Eleanor “Nelly” the estate. Their aim was to create a farming T r i e Custis, on her marriage to his nephew Lawrence community of free African Americans and white V , TION ag A y t V i t Lewis. Washington selected the home site settlers to prove that small farms could succeed r e himself, carving nearly 2,000 acres from his with free labor in this slave-holding state. oun H Mount Vernon Estate. It included Washington’s C ac x Gristmill & Distillery (below), the largest producer The Quakers lived and worshipped in the a f om Woodlawn home until their more modest r t of whiskey in America at the time. o ai farmhouses and meetinghouse (below) were F P Completed in 1805, the Woodlawn Home soon built. Over forty families from Quaker, Baptist, TIONAL TRUST FOR HISTORIC PRESER became a cultural center. The Lewises hosted and Methodist faiths joined this diverse, ”free- many notable guests, including John Adams, labor” settlement that fl ourished into the early Robert E. Lee and the Marquis de Lafayette. 20th century. TESY OF THE NA COUR t Woodlawn became the fi rst property c of The National Trust for Historic Preservation in 1951. This private non- ri profi t is dedicated to working with t communities to save historic places. s i When construction of Route 66 threatened the nearby Pope-Leighey House (below), designed by renowned D architect Frank Lloyd Wright, the c National Trust relocated this historic home to Woodlawn. -

Bibliography

Professor Peter Henriques, Emeritus E-Mail: [email protected] Recommended Books on George Washington 1. Paul Longmore, The Invention of GW 2. Noemie Emery, Washington: A Biography 3. James Flexner, GW: Indispensable Man 4. Richard Norton Smith, Patriarch 5. Richard Brookhiser, Founding Father 6. Marcus Cunliffe, GW: Man and Monument 7. Robert Jones, George Washington [2002 edition] 8. Don Higginbotham, GW: Uniting a Nation 9. Jack Warren, The Presidency of George Washington 10. Peter Henriques, George Washington [a brief biography for the National Park Service. $10.00 per copy including shipping.] Note: Most books can be purchased at amazon.com. A Few Important George Washington Web sites http://chnm.gmu.edu/courses/henriques/hist615/index.htm [This is my primitive website on GW and has links to most of the websites listed below plus other material on George Washington.] www.virginia.edu/gwpapers [Website for GW papers at UVA. Excellent.] http://etext.virginia.edu/washington [The Fitzpatrick edition of the GW Papers, all word searchable. A wonderful aid for getting letters on line.] http://georgewashington.si.edu [A great interactive site for students of all grades focusing on Gilbert Stuart’s Lansdowne portrait of GW.] http://www.yale.edu/lawweb/avalon/presiden/washpap.htm [The Avalon Project which contains GW’s inaugural addresses and many speeches.] http://www.mountvernon.org [The website for Mount Vernon.] Additional Books and Websites, 2004 Joe Ellis, His Excellency, October 2004 [This will be a very important book by a Pulitzer winning -

Carlyle Connection Sarah Carlyle Herbert’S Elusive Spinet - the Washington Connection by Richard Klingenmaier

The Friends of Carlyle House Newsletter Spring 2017 “It’s a fine beginning.” CarlyleCarlyle Connection Sarah Carlyle Herbert’s Elusive Spinet - The Washington Connection By Richard Klingenmaier “My Sally is just beginning her Spinnet” & Co… for Miss Patsy”, dated October 12, 1761, George John Carlyle, 1766 (1) Washington requested: “1 Very good Spinit (sic) to be made by Mr. Plinius, Harpsichord Maker in South Audley Of the furnishings known or believed to have been in John Street Grosvenor Square.” (2) Although surviving accounts Carlyle’s house in Alexandria, Virginia, none is more do not indicate when that spinet actually arrived at Mount fascinating than Sarah Carlyle Herbert’s elusive spinet. Vernon, it would have been there by 1765 when Research confirms that, indeed, Sarah owned a spinet, that Washington hired John Stadler, a German born “Musick it was present in the Carlyle House both before and after Professor” to provide Mrs. Washington and her two her marriage to William Herbert and probably, that it children singing and music lessons. Patsy was to learn to remained there throughout her long life. play the spinet, and her brother Jacky “the fiddle.” Entries in Washington’s diary show that Stadler regularly visited The story of Mount Vernon for the next six years, clear testimony of Sarah Carlyle the respect shown for his services by the Washington Herbert’s family. (3) As tutor Philip Vickers Fithian of Nomini Hall spinet actually would later write of Stadler, “…his entire good-Nature, begins at Cheerfulness, Simplicity & Skill in Music have fixed him Mount Vernon firm in my esteem.” (4) shortly after George Beginning in 1766, Sarah (“Sally”) Carlyle, eldest daughter Washington of wealthy Alexandria merchant John Carlyle and married childhood friend of Patsy Custis, joined the two Custis Martha children for singing and music lessons at the invitation of Dandridge George Washington. -

Who Was George Washington?

Book Notes: Reading in the Time of Coronavirus By Jefferson Scholar-in-Residence Dr. Andrew Roth Who was George Washington? ** What could be controversial about George Washington? Well, you might be surprised. The recently issued 1776 Project Report [1] describes him as a peerless hero of American freedom while the San Francisco Board of Education just erased his name from school buildings because he was a slave owner and had, shall we say, a troubled relationship with native Americans. [2] Which view is true? The 1776 Project’s view, which The Heritage Foundation called “a celebration of America,” [3] or the San Francisco Board of Education’s? [4] This is only the most recent skirmish in “the history wars,” which, whether from the political right’s attempt to whitewash American history as an ever more glorious ascent or the “woke” left’s attempt to reveal every blemish, every wrong ever done in America’s name, are a political struggle for control of America’s past in order to control its future. Both competing politically correct “isms” fail to see the American story’s rich weave of human aspiration as imperfect people seek to create a more perfect union. To say they never stumble, to say they never fall short of their ideals is one sort of lie; to say they are mere hypocrites who frequently betray the very ideals they preach is another sort of lie. In reality, Americans are both – they are idealists who seek to bring forth upon this continent, in Lincoln’s phrase, “government of the people, by the people, for the people” while on many occasions tripping over themselves and falling short. -

Mount Rushmore

MOUNT RUSHMORE National Memorial SOUTH DAKOTA of Mount Rushmore. This robust man with The model was first measured by fastening a his great variety of interests and talents left horizontal bar on the top and center of the head. As this extended out over the face a plumb bob MOUNT RUSHMORE his mark on his country. His career encom was dropped to the point of the nose, or other passed roles of political reformer, trust buster, projections of the face. Since the model of Wash rancher, soldier, writer, historian, explorer, ington's face was five feet tall, these measurements hunter, conservationist, and vigorous execu were then multiplied by twelve and transferred to NATIONAL MEMORIAL the mountain by using a similar but larger device. tive of his country. He was equally at home Instead of a small beam, a thirty-foot swinging on the western range, in an eastern drawing Four giants of American history are memorialized here in lasting granite, their likenesses boom was used, connected to the stone which would room, or at the Court of St. James. He typi ultimately be the top of Washington's head and carved in proportions symbolical of greatness. fied the virile American of the last quarter extending over the granite cliff. A plumb bob of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th was lowered from the boom. The problem was to adjust the measurements from the scale of the centuries. More than most Presidents, he and he presided over the Constitutional Con model to the mountain. The first step was to locate On the granite face of 6,000-foot high knew the West. -

National US History Bee Round #1

National US History Bee Round 1 1. This group had a member who used the alias “Robert Rich” when writing The Brave One and who had previously written the anti-war novel Johnny Get Your Gun. This group was vindicated when member Dalton Trumbo received a credit for the movie Spartacus. Who were these screenwriters cited for contempt of Congress and blacklisted after refusing to testify before the anti-Communist HUAC? ANSWER: Hollywood Ten 052-13-92-01101 2. This man is seen pointing to a curiously bewigged child in a Grant Wood painting about his “fable.” This man invented a popular story in which a father praises the “act of heroism” of his son when the latter insists “I cannot tell a lie” after cutting down a cherry tree. Who is this man who invented numerous stories about George Washington for an 1800 biography? ANSWER: Parson Weems [or Mason Locke Weems] 052-13-92-01102 3. This building is depicted in Charles Wilson Peale’s self-portrait The Artist in His Museum. This building is where James Wilson proposed a compromise in a meeting convened after the Annapolis Convention suggested revising the Articles of Confederation. What is this Philadelphia building, the site of the Constitutional Convention? ANSWER: Independence Hall [or Old State House of Pennsylvania] 052-13-92-01103 4. This event's completion resulted in Major Ridge and Elias Boudinot's assassination by dissidents. This event was put into action after the Treaty of New Echota was signed. This event began at Red Clay, Tennessee, and many participants froze to death at places like Mantle Rock. -

Deshler-Morris House

DESHLER-MORRIS HOUSE Part of Independence National Historical Park, Pennsylvania Sir William Howe YELLOW FEVER in the NATION'S CAPITAL DAVID DESHLER'S ELEGANT HOUSE In 1790 the Federal Government moved from New York to Philadelphia, in time for the final session of Germantown was 90 years in the making when the First Congress under the Constitution. To an David Deshler in 1772 chose an "airy, high situation, already overflowing commercial metropolis were added commanding an agreeable prospect of the adjoining the offices of Congress and the executive departments, country" for his new residence. The site lay in the while an expanding State government took whatever center of a straggling village whose German-speaking other space could be found. A colony of diplomats inhabitants combined farming with handicraft for a and assorted petitioners of Congress clustered around livelihood. They sold their produce in Philadelphia, the new center of government. but sent their linen, wool stockings, and leatherwork Late in the summer of 1793 yellow fever struck and to more distant markets. For decades the town put a "strange and melancholy . mask on the once had enjoyed a reputation conferred by the civilizing carefree face of a thriving city." Fortunately, Congress influence of Christopher Sower's German-language was out of session. The Supreme Court met for a press. single day in August and adjourned without trying a Germantown's comfortable upland location, not far case of importance. The executive branch stayed in from fast-growing Philadelphia, had long attracted town only through the first days of September. Secre families of means. -

Rembrandt Peale, Charles Willson Peale, and the American Portrait Tradition

In the Shadow of His Father: Rembrandt Peale, Charles Willson Peale, and the American Portrait Tradition URING His LIFETIME, Rembrandt Peale lived in the shadow of his father, Charles Willson Peale (Fig. 8). In the years that Dfollowed Rembrandt's death, his career and reputation contin- ued to be eclipsed by his father's more colorful and more productive life as successful artist, museum keeper, inventor, and naturalist. Just as Rembrandt's life pales in comparison to his father's, so does his art. When we contemplate the large number and variety of works in the elder Peak's oeuvre—the heroic portraits in the grand manner, sensitive half-lengths and dignified busts, charming conversation pieces, miniatures, history paintings, still lifes, landscapes, and even genre—we are awed by the man's inventiveness, originality, energy, and daring. Rembrandt's work does not affect us in the same way. We feel great respect for his technique, pleasure in some truly beau- tiful paintings, such as Rubens Peale with a Geranium (1801: National Gallery of Art), and intellectual interest in some penetrating char- acterizations, such as his William Findley (Fig. 16). We are impressed by Rembrandt's sensitive use of color and atmosphere and by his talent for clear and direct portraiture. However, except for that brief moment following his return from Paris in 1810 when he aspired to history painting, Rembrandt's work has a limited range: simple half- length or bust-size portraits devoid, for the most part, of accessories or complicated allusions. It is the narrow and somewhat repetitive nature of his canvases in comparison with the extent and variety of his father's work that has given Rembrandt the reputation of being an uninteresting artist, whose work comes to life only in the portraits of intimate friends or members of his family. -

Download Download

TEMPERANCE, ABOLITION, OH MY!: JAMES GOODWYN CLONNEY’S PROBLEMS WITH PAINTING THE FOURTH OF JULY Erika Schneider Framingham State College n 1839, James Goodwyn Clonney (1812–1867) began work on a large-scale, multi-figure composition, Militia Training (originally Ititled Fourth of July ), destined to be the most ambitious piece of his career [ Figure 1 ]. British-born and recently naturalized as an American citizen, Clonney wanted the American art world to consider him a major artist, and he chose a subject replete with American tradition and patriotism. Examining the numer- ous preparatory sketches for the painting reveals that Clonney changed key figures from Caucasian to African American—both to make the work more typically American and to exploit the popular humor of the stereotypes. However, critics found fault with the subject’s overall lack of decorum, tellingly with the drunken behavior and not with the African American stereotypes. The Fourth of July had increasingly become a problematic holi- day for many influential political forces such as temperance and abolitionist groups. Perhaps reflecting some of these pressures, when the image was engraved in 1843, the title changed to Militia Training , the title it is known by today. This essay will pennsylvania history: a journal of mid-atlantic studies, vol. 77, no. 3, 2010. Copyright © 2010 The Pennsylvania Historical Association This content downloaded from 128.118.152.206 on Thu, 21 Jan 2016 14:57:03 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions PAH77.3_02Schneider.indd 303 6/29/10 11:00:40 AM pennsylvania history demonstrate how Clonney reflected his time period, attempted to pander to the public, yet failed to achieve critical success.