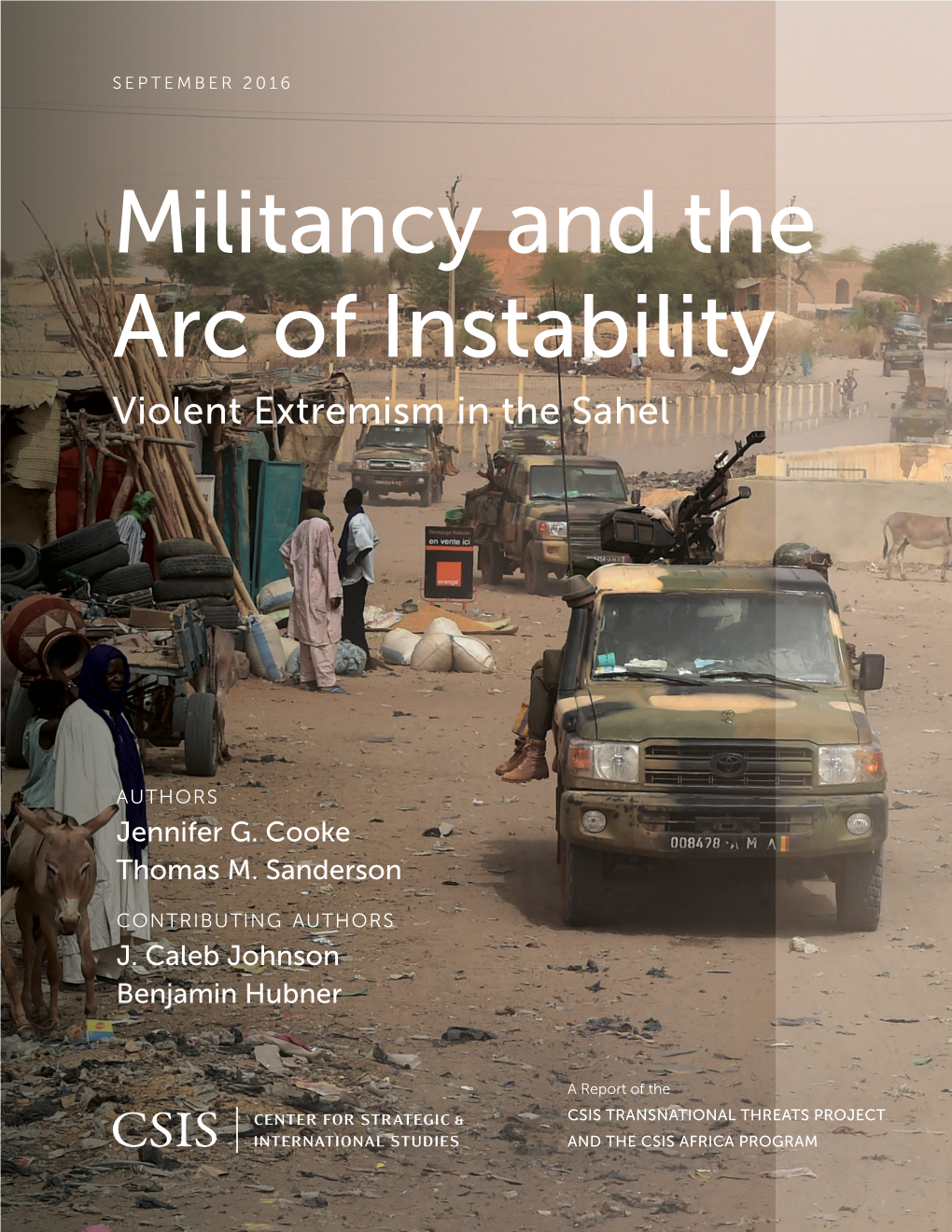

Militancy and the Arc of Instability: Violent Extremism in the Sahel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jihadism in Africa Local Causes, Regional Expansion, International Alliances

SWP Research Paper Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik German Institute for International and Security Affairs Guido Steinberg and Annette Weber (Eds.) Jihadism in Africa Local Causes, Regional Expansion, International Alliances RP 5 June 2015 Berlin All rights reserved. © Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik, 2015 SWP Research Papers are peer reviewed by senior researchers and the execu- tive board of the Institute. They express exclusively the personal views of the authors. SWP Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik German Institute for International and Security Affairs Ludwigkirchplatz 34 10719 Berlin Germany Phone +49 30 880 07-0 Fax +49 30 880 07-100 www.swp-berlin.org [email protected] ISSN 1863-1053 Translation by Meredith Dale (Updated English version of SWP-Studie 7/2015) Table of Contents 5 Problems and Recommendations 7 Jihadism in Africa: An Introduction Guido Steinberg and Annette Weber 13 Al-Shabaab: Youth without God Annette Weber 31 Libya: A Jihadist Growth Market Wolfram Lacher 51 Going “Glocal”: Jihadism in Algeria and Tunisia Isabelle Werenfels 69 Spreading Local Roots: AQIM and Its Offshoots in the Sahara Wolfram Lacher and Guido Steinberg 85 Boko Haram: Threat to Nigeria and Its Northern Neighbours Moritz Hütte, Guido Steinberg and Annette Weber 99 Conclusions and Recommendations Guido Steinberg and Annette Weber 103 Appendix 103 Abbreviations 104 The Authors Problems and Recommendations Jihadism in Africa: Local Causes, Regional Expansion, International Alliances The transnational terrorism of the twenty-first century feeds on local and regional conflicts, without which most terrorist groups would never have appeared in the first place. That is the case in Afghanistan and Pakistan, Syria and Iraq, as well as in North and West Africa and the Horn of Africa. -

Somalia's Al-Shabaab and the Global Jihad Network

Terrorism without Borders: Somalia’s Al-Shabaab and the global jihad network by Daniel E. Agbiboa This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License. Abstract This article sets out to explore the evolution, operational strategy and transnational dimensions of Harakat Al-Shabab al-Mujahedeen (aka Al-Shabab), the Somali-based Islamist terrorist group. The article argues that Al-Shabab’s latest Westgate attack in Kenya should be understood in the light of the group’s deepening ties with Al-Qaeda and its global jihad, especially since 2009 when Al-Shabab formally pledged allegiance to Osama bin Laden’s Al-Qaeda and welcomed the organisation’s core members into its leadership. Key words: Al-Shabab, Westgate Attack; Al-Qaeda; Global Jihad; Kenya; Somalia. Introduction n 21 September 2013, the world watched with horror as a group of Islamist gunmen stormed Kenya’s high-end Westgate Mall in Nairobi and fired at weekend shoppers, killing over 80 people. The gunmen reportedly shouted in Swahili that Muslims would be allowed to leave while all others Owere subjected to their bloodletting (Agbiboa, 2013a). Countries like France, Canada, the United States, the United Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand, and Ghana, among others, all confirmed that their citizens were among those affected. The renowned Ghanaian Poet, Kofi Awoonor, was also confirmed dead in the attack (Mamdani, 2013). The Somali-based and Al-Qaeda-affiliated Islamist terrorist group, Harakat Al-Shabab al-Mujahideen or, more commonly, Al-Shabab – “the youth” in Arabic – have since claimed responsibility for the horrific attack through its Twitter account. -

Social Media in Africa

Social media in Africa A double-edged sword for security and development Technical annex Kate Cox, William Marcellino, Jacopo Bellasio, Antonia Ward, Katerina Galai, Sofia Meranto, Giacomo Persi Paoli Table of contents Table of contents ...................................................................................................................................... iii List of figures ........................................................................................................................................... iv List of tables .............................................................................................................................................. v Abbreviations .......................................................................................................................................... vii Annex A: Overview of Technical Annex .................................................................................................... 1 Annex B: Background to al-Shabaab, Boko Haram and ISIL ..................................................................... 3 Annex C: Timeline of significant dates ...................................................................................................... 9 Annex D: Country profiles ...................................................................................................................... 25 Annex E: Social media and communications platforms ............................................................................ 31 Annex F: Twitter data -

Boko Haram and Ansaru - Council on Foreign Relations

Nigeria's Boko Haram and Ansaru - Council on Foreign Relations http://www.cfr.org/nigeria/boko-haram/p25739 Backgrounders Boko Haram Authors: Mohammed Aly Sergie, and Toni Johnson Updated: October 7, 2014 Introduction Boko Haram, a diffuse Islamist sect, has attacked Nigeria's police and military, politicians, schools, religious buildings, public institutions, and civilians with increasing regularity since 2009. More than five thousand people have been killed in Boko Haram-related violence, and three hundred thousand have been displaced. Some experts view the group as an armed revolt against government corruption, abusive security forces, and widening regional economic disparity. They argue that Abuja should do more to address the strife between the disaffected Muslim north and the Christian south. The U.S. Department of State designated Boko Haram a foreign terrorist organization in 2013. Boko Haram's brutal campaign includes a suicide attack on a United Nations building in Abuja in 2011, repeated attacks that have killed dozens of students, the burning of villages, ties to regional terror groups, and the abduction of more than two hundred girls in April 2014. The Nigerian government hasn't been able to quell the insurgency, and in May 2014 the United States deployed a small group of military advisers to help find the kidnapped girls. The Road to Radicalization Boko Haram was created in 2002 in Maiduguri, the capital of the northeastern state of Borno, by Islamist cleric Mohammed Yusuf. The group aims to establish a fully Islamic state in Nigeria, including the implementation of criminal sharia courts across the country. Paul Lubeck, a University of California, Santa Cruz professor who researches Muslim societies in Africa, says Yusuf was a trained Salafist (an adherent of a school of thought often associated with jihad), and was strongly influenced by Ibn Taymiyyah, a fourteenth-century legal scholar who preached Islamic fundamentalism and is an important figure for radical groups in the Middle East. -

Boko Haram in the Context of Global Jihadism: a Conceptual Analysis of Violent Extremism in Northern Nigeria and Counter-Terrorism Measures

BOKO HARAM IN THE CONTEXT OF GLOBAL JIHADISM: A CONCEPTUAL ANALYSIS OF VIOLENT EXTREMISM IN NORTHERN NIGERIA AND COUNTER-TERRORISM MEASURES MARK D. KIELSGARD* AND NABIL M. ORINA** ABSTRACT This Article aims to fill a gap in the literature through a conceptual analysis of Boko Haram’s global nature and utilizing that analysis to evaluate current counter-terrorism measures against the group. Central to this analysis will be the question of whether the group can be categorized as a global jihadist group. Global jihadism is understood in this Article as a pan-Islamist movement against Western interests. This Article argues that status as a global jihadist organization and hierarchy within the world’s global jihadist movement are best evaluated on a three-criteria approach using the indicators of conforming ideology, militant operations/targets, and external relations or cooperation. It will be further argued that these criteria are important not only to provide a more comprehensive way of thinking of international terrorism but also in creating * Dr. Mark D. Kielsgard is an Associate Professor of Law at City University of Hong Kong where he serves as the Program Director for the JD program, Associate Director and co-founder of the Centre for Public Law and Human Rights, and is a member of the Centre for Public Affairs and Law (CPAL). His research focuses on criminal law and human rights, and he has published widely on terrorism, genocide, and international criminal law. ** Nabil M. Orina is a Lecturer at Moi University, School of Law, Kenya and a Postdoctoral Research Fellow at the Centre of Excellence for International Courts (iCourts), Faculty of Law, University of Copenhagen. -

Country Reports on Terrorism 2019

Country Reports on Terrorism 2019 BUREAU OF COUNTERTERRORISM Country Reports on Terrorism 2019 is submitted in compliance with Title 22 of the United States Code, Section 2656f (the “Act”), which requires the Department of State to provide to Congress a full and complete annual report on terrorism for those countries and groups meeting the criteria of the Act. Foreword In 2019, the United States and our partners made major strides to defeat and degrade international terrorist organizations. Along with the Global Coalition to Defeat ISIS, in March, the United States completed the destruction of the so-called “caliphate” in Iraq and Syria. In October, the United States launched a military operation that resulted in the death of Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, the self-proclaimed “caliph” of ISIS. As part of the maximum pressure campaign against the Iranian regime – the world’s worst state sponsor of terrorism – the United States and our partners imposed new sanctions on Tehran and its proxies. In April, the United States designated Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), including its Qods Force, as a Foreign Terrorist Organization (FTO) – the first time such a designation has been applied to part of another government. And throughout the year, a number of countries in Western Europe and South America joined the United States in designating Iran-backed Hizballah as a terrorist group in its entirety. Despite these successes, dangerous terrorist threats persisted around the world. Even as ISIS lost its leader and territory, the group adapted to continue the fight from its affiliates across the globe and by inspiring followers to commit attacks. -

GEOPOLITICS of the 2016 AUSTRALIAN DEFENSE WHITE PAPER and ITS PREDECESSORS Bert Chapman Purdue University, [email protected]

Purdue University Purdue e-Pubs Libraries Faculty and Staff choS larship and Research Purdue Libraries 4-25-2016 GEOPOLITICS OF THE 2016 AUSTRALIAN DEFENSE WHITE PAPER AND ITS PREDECESSORS Bert Chapman Purdue University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://docs.lib.purdue.edu/lib_fsdocs Part of the Australian Studies Commons, Comparative Politics Commons, Defense and Security Studies Commons, Economic Policy Commons, Geography Commons, History of the Pacific Islands Commons, Industrial Organization Commons, International and Area Studies Commons, International Relations Commons, Military History Commons, Military Studies Commons, Peace and Conflict Studies Commons, Political Economy Commons, Political History Commons, Public Economics Commons, and the Public Policy Commons Recommended Citation Bert Chapman."Geopolitics of the 2016 Australian Defense White Paper and Its Predecessors." Geopolitics, History, and International Relations, 9 (1)(2017): 17-67. This document has been made available through Purdue e-Pubs, a service of the Purdue University Libraries. Please contact [email protected] for additional information. Geopolitics, History, and International Relations 9(1) 2017, pp. 17–67, ISSN 1948-9145, eISSN 2374-4383 GEOPOLITICS OF THE 2016 AUSTRALIAN DEFENSE WHITE PAPER AND ITS PREDECESSORS BERT CHAPMAN [email protected] Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN ABSTRACT. Australia released the newest edition of its Defense White Paper, describing Canberra’s current and emerging national security priorities, on February 25, 2016. This continues a tradition of issuing defense white papers since 1976. This work will examine and analyze the contents of this document as well as previous Australian defense white papers, scholarly literature, and political statements assess- ing their geopolitical significance. -

Maritime Security Issues in an Arc of Instability and Opportunity Walter S

University of Wollongong Research Online Faculty of Law, Humanities and the Arts - Papers Faculty of Law, Humanities and the Arts 2013 Maritime Security Issues in an Arc of Instability and Opportunity Walter S. Bateman University of Wollongong, [email protected] Quentin A. Hanich University of Wollongong, [email protected] Publication Details Bateman, S. & Hanich, Q. (2013). Maritime Security Issues in an Arc of Instability and Opportunity. Security Challenges, 9 (4), 87-105. Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] Maritime Security Issues in an Arc of Instability and Opportunity Abstract The aP cific Arc of islands and archipelagos to the north and east of Australia has been characterised both as an ‗arc of instability' and as an ‗arc of opportunity'. It is the region from or through which a threat to Australia could most easily be posed, as well as an area providing opportunities for Australia to work on common interests with the ultimate objective of a more secure and stable region. Maritime issues are prominent among these common interests. This article identifies these issues and their relevance to Australia's maritime strategy. It suggests measures Australia might take to exploit the opportunities these interests provide. Keywords arc, issues, instability, maritime, opportunity, security Disciplines Arts and Humanities | Law Publication Details Bateman, S. & Hanich, Q. (2013). Maritime Security Issues in an Arc of Instability and Opportunity. Security Challenges, 9 (4), 87-105. This journal article is available at Research Online: http://ro.uow.edu.au/lhapapers/3256 Maritime Security Issues in an Arc of Instability and Opportunity Sam Bateman and Quentin Hanich The Pacific Arc of islands and archipelagos to the north and east of Australia has been characterised both as an ‗arc of instability‘ and as an ‗arc of opportunity‘. -

Zenn 1 “The Continuing Threat of Boko Haram” Testimony Before The

“The Continuing Threat of Boko Haram” Testimony before the Subcommittee on Africa, Global Health, Global Human Rights, and International Organizations and Subcommittee on Terrorism, Nonproliferation, and Trade November 13, 2013 Members of Congress, Ladies and Gentlemen: My name is Jacob Zenn. I am a Research Analyst of African and Eurasian Affairs for The Jamestown Foundation. The views I express in this testimony are my own. Thank you for inviting me to testify before you today on the topic of "The Continuing Threat of Boko Haram." In this testimony, I will answer the following questions: • How can the U.S. support Nigeria counter terrorist groups? • Who is Boko Haram and who is Ansaru? • Where do Boko Haram and Ansaru get their funding? • Are Boko Haram and Ansaru connected to al-Qaeda? • Do Boko Haram and Ansaru present a threat beyond Nigeria? 1. How can the U.S. support Nigeria counter terrorist groups? Below are 10 measures the U.S. can take to support Nigerian counter-terrorism efforts: • Develop a ‘Marshall Plan’ for northeastern Nigeria and use those funds to build schools, hospitals, infrastructure, water sources and recreational facilities, especially after army offensives clear out Boko Haram insurgents. The program would need to be transparent and have strong leadership to ensure projects are implemented. • Label Boko Haram as a “foreign terrorist organization (FTO),” which could bring the power of international financial and anti-money laundering institutions to bear on Boko Haram’s financial sponsors. Otherwise, this label is meaningless and should be abandoned; if Boko Haram is not an FTO, then who is? • Mentor Nigerian troops in counter-insurgency based on best practices learned from years of dealing with IEDs, urban warfare and ambushes in Iraq and Afghanistan. -

Boko Haram's Fluctuating Affiliations

Boko Haram Beyond the Headlines: Analyses of Africa’s Enduring Insurgency Editor: Jacob Zenn ZENN BOKO HARAM BEYOND THE HEADLINES MAY 2018 CHAPTER 6: Boko Haram’s Fluctuating Affiliations: Future Prospects for Realignment with al-Qa`ida By Jacob Zenn Introduction The group commonly known as “Boko Haram”613 has gained international notoriety in recent years. First, it claimed to have ‘enslaved’ more than 200 schoolgirls in Chibok, Nigeria, in May 2014, which led to an international outcry and the founding of a global social media movement calling for the girls’ release, #BringBackOurGirls. The movement finally pressured the Nigerian government to negotiate for the release of more than 100 of the girls in 2016 and 2017. While Boko Haram was holding these girls captive, it also merged with the Islamic State in March 2015. The Islamic State’s acceptance of Boko Haram leader Abu Bakr Shekau’s pledge to Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi led to the renaming of Boko Haram from its former ofcial title, Jama`at Ahl al-Sunna li- Da`wa wa-l-Jihad,614 to Islamic State in West Africa Province (al-Dawla al-Islamiya fi Wilayat Gharb Ifriqiya), or ISWAP, as well as the Islamic State’s upgrading of the new ISWAP’s media operations.615 Despite that the Islamic State has also “commanded the world’s attention” in recent years, including for its merger with Boko Haram, out of the media glare al-Qa`ida has, according to terrorism scholar Bruce Hofman, “been quietly rebuilding and fortifying its various branches.”616 Indeed, prior to 2015, the nature and extent of Boko Haram’s -

Australia: Background and U.S. Relations

Order Code RL33010 Australia: Background and U.S. Relations Updated August 8, 2008 Bruce Vaughn Specialist in Asian Affairs Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Australia: Background and U.S. Relations Summary The Commonwealth of Australia and the United States are very close allies. Australia shares similar cultural traditions and values with the United States and has been a treaty ally since the signing of the Australia-New Zealand-United States (ANZUS) Treaty in 1951. Australia made major contributions to the allied cause in both the first and second World Wars and has been a staunch ally of Britain and the United States in their conflicts. Under the former Liberal government of John Howard, Australia invoked the ANZUS treaty to offer assistance to the United States after the attacks of September 11, 2001, in which 22 Australians died. Australia was one of the first countries to commit troops to U.S. military operations in Afghanistan and Iraq. In October 2002, a terrorist attack on Western tourists in Bali, Indonesia, killed more than 200 persons, including 88 Australians and seven Americans. A second terrorist bombing, which killed 23, including four Australians, was carried out in Bali in October 2005. The Australian Embassy in Jakarta, Indonesia, was also bombed by members of Jemaah Islamiya (JI) in September 2004. Kevin Rudd, of the Labor Party, was elected prime minister on November 24, 2007. While Rudd has fulfilled an election promise to draw down Australian military forces in Iraq and has reversed Australia’s position on climate change — by signing the Kyoto protocols — relations with the United States remain very close. -

Arc of Instability’: the History of an Idea

Chapter 6 The ‘Arc of Instability’: The History of an Idea Graeme Dobell It is extremely important to us as Australians that we appreciate that we cannot afford to have failing states in our region. The so-called arc of instability, which basically goes from East Timor through to the south-west Pacific states, means not only that Australia does have a responsibility to prevent humanitarian disaster and assist with humanitarian and disaster relief but also that we cannot allow any of these countries to become havens for transnational crime or indeed havens for terrorism ¼ Australia has a responsibility in protecting our own interests and values to support the defence and protection of the interests and values of these countries in our region. Brendan Nelson Defence Minister1 The reason why we need a bigger Australian Army is self evident. This country faces on-going and in my opinion increasing instances of destabilised and failing states in our own region. I believe in the next 10 to 20 years Australia will face a number of situations the equivalent of or potentially more challenging than the Solomon Islands and East Timor. John Howard, Prime Minister2 Not enough jobs is leading to poverty, unhappiness, and it results in crime, violence and instability. In the Pacific, this could lead to a lost generation of young people. Alexander Downer Foreign Affairs Minister3 85 History as Policy What's sometimes called the `arc of instability' may well become the `arc of chaos'. We've seen in the Solomon Islands and elsewhere evidence of what happens when young people do not have opportunities, don©t have a sense of hope for their own future.