EDITING ROLLS of ARMS Some Reflections on Basic Principles John A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

John Archibald Goodall, F.S.A

Third Series Vol. II part 1. ISSN 0010-003X No. 211 Price £12.00 Spring 2006 THE COAT OF ARMS an heraldic journal published twice yearly by The Heraldry Society THE COAT OF ARMS The journal of the Heraldry Society Third series Volume II 2006 Part 1 Number 211 in the original series started in 1952 The Coat of Arms is published twice a year by The Heraldry Society, whose registered office is 53 High Street, Burnham, Slough SL1 7JX. The Society was registered in England in 1956 as registered charity no. 241456. Founding Editor † John Brooke-Little, C.V.O., M.A., F.H.S. Honorary Editors C. E. A. Cheesman, M.A., PH.D., Rouge Dragon Pursuivant M. P. D. O'Donoghue, M.A., Bluemantle Pursuivant Editorial Committee Adrian Ailes, B.A., F.S.A., F.H.S. Andrew Hanham, B.A., PH.D Advertizing Manager John Tunesi of Liongam PLATE 3 . F.S.A , Goodall . A . A n Joh : Photo JOHN GOODALL (1930-2005) Photographed in the library of the Society of Antiquaries with a copy of the Parliamentary Roll (ed. N.H. Nicolas, 1829). JOHN ARCHIBALD GOODALL, F.S.A. (1930-2005) John Goodall, a member of the editorial committee of this journal, and once a fre• quent contributor to its pages, died in St Thomas' Hospital of an infection on 23 November 2005. He was suffering from cancer. His prodigiously wide learning spread back to the Byzantine and ancient worlds, and as far afield as China and Japan, but particularly focused on medieval rolls of arms, on memorial brasses and on European heraldry. -

A Visual Guide to Identifying Cats

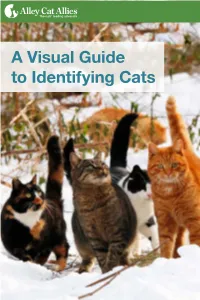

A Visual Guide to Identifying Cats When cats have similar colors and patterns, like two gray tabbies, it can seem impossible to tell them apart! That is, until you take note of even the smallest details in their appearance. Knowledge is power, whether you’re an animal control officer or animal Coat Length shelter employee who needs to identify cats regularly, or you want to identify your own cat. This guide covers cats’ traits from their overall looks, like coat pattern, to their tiniest features, like whisker color. Let’s use our office cats as examples: • Oliver (left): neutered male, shorthair, solid black, pale green eyes, black Hairless whiskers, a black nose, and black Hairless cats have no fur. paw pads. • Charles (right): neutered male, shorthair, brown mackerel tabby with spots toward his rear, yellow-green eyes, white whiskers with some black at the roots, a pink-brown nose, and black paw pads. Shorthair Shorthair cats have short fur across As you go through this guide, remember that certain patterns and markings the entire body. originated with specific breeds. However, these traits now appear in many cats because of random mating. This guide covers the following features: Coat Length ...............................................................................................3 Medium hair Coat Color ...................................................................................................4 Medium hair cats have longer fur around the mane, tail, and/or rear. Coat Patterns ..............................................................................................6 -

Heraldic Terms

HERALDIC TERMS The following terms, and their definitions, are used in heraldry. Some terms and practices were used in period real-world heraldry only. Some terms and practices are used in modern real-world heraldry only. Other terms and practices are used in SCA heraldry only. Most are used in both real-world and SCA heraldry. All are presented here as an aid to heraldic research and education. A LA CUISSE, A LA QUISE - at the thigh ABAISED, ABAISSÉ, ABASED - a charge or element depicted lower than its normal position ABATEMENTS - marks of disgrace placed on the shield of an offender of the law. There are extreme few records of such being employed, and then only noted in rolls. (As who would display their device if it had an abatement on it?) ABISME - a minor charge in the center of the shield drawn smaller than usual ABOUTÉ - end to end ABOVE - an ambiguous term which should be avoided in blazon. Generally, two charges one of which is above the other on the field can be blazoned better as "in pale an X and a Y" or "an A and in chief a B". See atop, ensigned. ABYSS - a minor charge in the center of the shield drawn smaller than usual ACCOLLÉ - (1) two shields side-by-side, sometimes united by their bottom tips overlapping or being connected to each other by their sides; (2) an animal with a crown, collar or other item around its neck; (3) keys, weapons or other implements placed saltirewise behind the shield in a heraldic display. -

Download the PDF Here

(We Would Like to Share) Our Blazon: Some Thoughts on a Possible School Badge (party) per bend sinister “The oblique stroke appears at first sight to be the signal that the binary opposition between categories (speech/ translated to English means: writing or love/hate) won’t hold — that neither of the words in opposition to each other is good for the fight. a blank shield with a single diagonal line running The stroke, like an over-vigilant referee, must keep them from the bottom left edge to the top right hand corner apart and yet still oversee the match.” —Steve Rushton The badge we would like to wear is two-faced — both founded on, and breaking from, established guidelines. Stripped to its Heraldry is a graphic language evolved from around 1130 ad to fundamentals, and described in heraldic vocabulary, it is UN- identify families, states and other social groups. Specific visual CHARGED. It is a schizophrenic frame, a paradox, a forward forms yield specific meanings, and these forms may be combined slash making a temporary alliance between categories, simultane- in an intricate syntax of meaning and representation. Any heraldic ously generic and/or specific. device is described by both a written description and its corre- sponding graphic form. The set of a priori written instructions is D/S called a Blazon — to give it form is to Emblazon. In order to ensure that the pictures drawn from the descriptions are accurate and reasonably alike, Blazons follow a strict set of rules and share a unique vocabulary. Objects, such as animals and shapes, are called Charges; colors are renamed, such as Argent for Silver or Or for Gold; and divisions are described in terms such as Dexter (“right” in Latin) and Sinister (“left”). -

Advantages, Shortcomings and Unused Potential. by Jack Carlson

Third Series Vol. V part 2. ISSN 0010-003X No. 218 Price £12.00 Autumn 2009 THE COAT OF ARMS an heraldic journal published twice yearly by The Heraldry Society THE COAT OF ARMS The journal of the Heraldry Society Third series Volume V 2009 Part 2 Number 218 in the original series started in 1952 The Coat of Arms is published twice a year by The Heraldry Society, whose registered office is 53 High Street, Burnham, Slough SL1 7JX. The Society was registered in England in 1956 as registered charity no. 241456. Founding Editor +John Brooke-Little, C.V.O., M.A., F.H.S. Honorary Editors C. E. A. Cheesman, M.A., PH.D., Rouge Dragon Pursuivant M. P. D. O'Donoghue, M.A., Bluemantle Pursuivant Editorial Committee Adrian Ailes, M.A., D.PHIL., F.S.A., F.H.S. Jackson W. Armstrong, B.A. Noel COX, LL.M., M.THEOL., PH.D., M.A., F.R.HIST.S. Andrew Hanham, B.A., PH.D. Advertizing Manager John Tunesi of Liongam INTERNET HERALDRY Advantages, Shortcomings and Unused Potential Jack Carlson In 1996, the Cambridge University Heraldic & Genealogical Society declared that 'genealogy and heraldry have both caught up with the latest computer technology' and that heraldists would soon prefer the internet to books: searchable heraldic databases and free, high-quality electronic articles and encyclopedias on the subject were imminent.1 Over the past thirteen years the internet's capabilities have likely surpassed what CUH&GS could have imagined. At the same time, it seems, the reality of heraldry's online presence falls somewhat short of the society's expectations. -

THE COAT of ARMS an Heraldic Journal Published Twice Yearly by the Heraldry Society the COAT of ARMS the Journal of the Heraldry Society

Third Series Vol. II part 2. ISSN 0010-003X No. 212 Price £12.00 Autumn 2006 THE COAT OF ARMS an heraldic journal published twice yearly by The Heraldry Society THE COAT OF ARMS The journal of the Heraldry Society Third series Volume II 2006 Part 2 Number 212 in the original series started in 1952 The Coat of Arms is published twice a year by The Heraldry Society, whose registered office is 53 High Street, Burnham, Slough SL1 7JX. The Society was registered in England in 1956 as registered charity no. 241456. Founding Editor † John Brooke-Little, C.V.O., M.A., F.H.S. Honorary Editors C. E. A. Cheesman, M.A., PH.D., Rouge Dragon Pursuivant M. P. D. O'Donoghue, M.A., Bluemantle Pursuivant Editorial Committee Adrian Ailes, B.A., F.S.A., F.H.S. Jackson W. Armstrong, B.A. Andrew Hanham, B.A., PH.D Advertizing Manager John Tunesi of Liongam PLATE 4 Osmond Barnes, Chief Herald at the Imperial Assemblage at Delhi, 1876-7 Private Collection. See page 108. HERALDS AT THE DELHI DURBARS Peter O 'Donoghue Three great imperial durbars took place on the Ridge outside Delhi during the height of the British Raj, on a site which was associated with the heroics of the Mutiny. The first durbar, in 1876-77, proclaimed Queen Victoria as Empress of India, whilst the second and third, in 1902-3 and 1911, proclaimed the accessions of Edward VII and George V respectively. All three drew upon Indian traditions of ceremonial meetings or durbars between rulers and ruled, and in particular upon the Mughal Empire's manner of expressing its power to its subject princes. -

THE ORIGINS of the “Mccrackens”

THE ORIGINS OF THE “McCrackens” By Philip D. Smith, Jr. PhD, FSTS, GTS, FSA Scot “B’e a’Ghaidhlig an canan na h’Albanaich” – “Gaelic was the language of the Scottish people.” The McCrackens are originally Scottish and speakers of the Scottish Gaelic language, a cousin to Irish Gaelic. While today, Gaelic is only spoken by a few thousands, it was the language of most of the people of the north and west of Scotland until after 1900. The McCracken history comes from a long tradition passed from generation to generation by the “seannachies”, the oral historians, of the Gaelic speaking peoples. According to tradition, the family is named for Nachten, Lord of Moray, a district in the northeast of Scotland. Nachten supposedly lived in the 9th century. In the course of time a number of his descendants moved southwest across Scotland and settled in Argyll. The family multiplied and prospered. The Gaelic word for “son” is “mac” and that for “children” is “clann” The descendants of Nachten were called by their neighbors, the Campbells, MacDougalls, and others the “Children of the Son of Nachten”, in Gaelic “Cloinne MacNachtain”, “Clan MacNachtan”. Spelling was not regularized in either Scotland or America until well after 1800. Two spellings alternate for the guttural /k/-like sound common in many Gaelic words, -ch and –gh. /ch/ is the most common Scottish spelling but the sound may be spelled –gh. The Scottish word for “lake” is “loch” while in Northern England and Ireland the same word is spelled “lough”. “MacLachlan” and “Mac Loughlin” are the same name as are “Docherty” and “Dougherty”. -

Heraldic Arms and Badges

the baronies of Duffus, Petty, Balvenie, Clan Heraldic Arms and Aberdour in the northeast of Murray Clan On 15 May 1990 the Court of Lord Scotland, as well as the lordships of Lyon granted The Murray Clan Society Bothwell and Drumsargard and a our armorial ensign or heraldic arms. An Society number of other baronies in lower armorial ensign is the design carried on Clydesdale. Sir Archibald, per the a flag or shield. English property law of jure uxoris, Latin for "by right of (his) wife" became the The Society arms are described on th th Clan Badges legal possessor of her lands. the 14 page of the 75 Volume of Our Public Register of All Arms and Bearings and Heraldic Which Crest Badge to Wear in Scotland, VIDELICT as: Azure, five Although Murrays were permitted to annulets conjoined in fess Argent wear either the mermaid or demi-man between three mullets of the Last. Above Arms crest badges, sometime in the late the Shield is placed an Helm suitable to Clan Badges 1960’s or early 1970’s, the Lord Lyon an incorporation (VIDELICET: a Sallet Prior to the advent of heraldry, King of Arms declared the demi-man Proper lined Scottish clansmen and clanswomen crest badge inappropriate. Since his Gules) with a wore badges to identify themselves. decisions on heraldic matters have the Clan badges were devices with family or force of law in Scotland, all the personal associations which identified manufacturers of clan badges, etc., the possessor, not unlike our modern ceased producing the demi-man. There class rings, military insignias, union pins, was a considerable amount of feeling on etc. -

1 President's Message

PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE by David M. Cvet Summer is upon us with a vengeance, breaking temperature records from the 1930's – at least in Toronto. The warmer weather has had some fits and starts, with warm weather followed by frost, causing newly planted peppers and tomatoes to be damaged beyond saving. However, these exciting events pale in comparison to seeing the Queen's Beasts (some depicted on the right) who will be attending the Society's formal dinner at this year's Annual General Meeting, scheduled for October 1-3, 2010 in Ottawa. The Annual Meeting itself will be held at the Delta Ottawa Hotel on Queen Street. The Saturday evening dinner will take place at the Canadian Museum of Civilization (across the Ottawa River in Gatineau, Quebec), which will provide a grand setting for our annual banquet, graced as it will be with these impressive “guests”. We are indeed grateful to David Rumball for organizing this event, and for arranging with the museum to have the Queen's Beasts available for the dinner. I encourage our members to make the necessary calendar and travel to enhance the “coolness” factor of the Society in order to attract arrangements to attend this splendid event. new members – and to retain our present ones. One important reason for having the AGM in Ottawa this year As an example, at the recent Toronto Branch AGM (combined (rather than being hosted by the Prairie Branch, as it would have with the Society's Board meeting earlier the same day) the been in the usual sequence) is the expectation that the new formal dinner at Hart House was visually recorded by a Canadian Heraldic Authority tabard (donated by the Society) photographer I had arranged as my guest. -

The Genetics of Plumage Color in Poultry

October, 1927 R esearch Bulletin No. 105 The Genetics of Plumage Color in Poultry By O. W. KNOX AGRICULTURAL EXPERIMENT STATION IOWA STATE OOLLEGE OF AGRICULTURE AND MEOHANIC ARTS POULTRY SECTION AMES, IOWA SUMMARY 1. The chromogen gene for color, CC, acted as a simple dominant. 2. The extension of black pigment, EE, was inherited on a simple monohybrid basis. 3. The heterozygous extension and chromogen genes (Cc Ee) had a balanced relationship. This combina tion of heterozygous factors weakened the expression of the black melanic pigment in the presence of two or more doses of buff. 4. Buff color was controlled on a dihybrid basis, the following symbols being used, Bu Bu Bu' Bu'. 5. Three or more doses of the buff genes in the pres ence of homozygous color factors, CC, were epistatic to black, and gave a buff color. 6. Two or more doses of the buff color determiners were epistatic to black when they were in the pres ence of both the extension of black and chromogen factors in a heterozygous state. 7. When the extension factor was homozygous, EE, the buff color was hypostatic to black if not present in three or more doses. 8. All the factors included thus far in the summary were autosomal. 9. The sex-linked factor for barring (BB and B-) ap peared to act as a simple dominant to black and buff colors. The Genetics of Plumage Color in Poultry By C. W. KNOX* Much information on the inheritance of the different color factors in poultry has accumulated since Bateson (2) first took up the study shortly after the rediscovery of Mendelian inheri tance in 1900. -

The Heraldry Society Annual Report of the Trustees and Unaudited Financial

THE HERALDRY SOCIETY ANNUAL REPORT OF THE TRUSTEES AND UNAUDITED FINANCIAL STATEMENTS YEAR ENDING 31 MARCH 2019 THE HERALDRY SOCIETY Annual Report of the Trustees and Financial Statements Year Ending 31 March 2019 _________________________________________________________________ CONTENTS Page Report of the Trustees 1 – 7 Report of the Independent Examiner 8 Statement of Financial Activities 9 Balance Sheet 10 – 11 Notes to the Financial Statements 12 – 16 Brief Biographies of the Trustees and Other Volunteer Officers 17 – 19 REFERENCE DETAILS Charity Registration Number Company Registration Number 241456 00572778 England & Wales Registered office Website (correspondence address) www.theheraldrysociety.com 53 Hitchin Street, Baldock, Hertfordshire, SG7 6AQ The Society does not have a central office. Trustees and other volunteers work from home. Secretary J J Tunesi of Liongam Independent Examiner E E Irvine FCA WMT – Chartered Accountants Verulam Point St Albans, Hertfordshire AL1 5HE The Society’s bank accounts are maintained at: CAF Bank Ltd Lloyds Bank plc 25 Kings Hill Avenue 1 Bircherley Street, Hertford, SG14 1BU West Malling, Kent, ME19 4JQ THE PRESIDENT AND THE VICE-PRESIDENTS OF THE SOCIETY The President His Grace the Duke of Norfolk Honorary Vice Presidents The following are deemed to hold this office by virtue of their title or position: The Lord High Constable of Scotland, the Earl of Erroll The Lord Lyon, the Revd Canon Dr Joseph J. Morrow CBE QC DL LLD The Chief Herald of Canada, Ms Claire Boudreau FRHSC AIH Garter King of -

America Heraldica : a Compilation of Coats of Arms, Crests and Mottoes Of

rF t T. Jo Goolidge AMERICA HERALDICA A COMPILATION OF flits fl} |rnis, |ttsts aifl Jfltoea OF PROMINENT AMERICAN FAMILIES SETTLED IN THIS COUNTRY BEFORE 1800 EDITED BY E. DE V' VERMONT ILLUSTRATED BY AUGUSTE,LEROY- IRew JDorft THE AMERICA HERALDICA PUBLISHING ASSOCIATION 744 BROADWAY Entered, according to Act of Congress, in the year i88g, by E. DB V. VERMONT, in the office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington. Ait rights reserved. Plates Engraved and Printed by Liebler & Maass, Letter-press by Haighl & Dudley, New York. Poughkeepsie. N. Y. ^r.,/,... AMERICA HERALDICA. PLATE I. gJUlVIRQSTOE VAK (o:\ 0]RTLftI2DT RCHEJ^ oy=ij=(is TTEftTHCOTE IJLIPSE VftB/teBSSELAElP^ CHVYLE]F^ OODHVLL %Aiy^AX .JilVJuKLEY JP^RKLIB OUTG^OmE'RY f^EUL> ^Bffi!^J\Y)^J^, PI NX. E. de V. VEJ^Orrr, Editor /^/^'^ ' / /}^-L. f-f"^-- / ^mi^^w- WI^Mmw'- AMERICA HERALDICA A COMPILATION OF Bits fit Irtus, psta aiil %'&iim OF PROMINENT AMERICAN FAMILIES SETTLED IN THIS COUNTRY BEFORE 1800 EDITED BY E. DE V. VERMONT ILLUSTRATED BY HENRY RYKERS BRENTANO BROTHERS lintcrcd, accuiiliili! in Act of Congress, in tll= year i8S6. by E. 1)K V. VKKMONT. in [he office of the Librarian of Congress, al Washington. W// / t^/ifs reserved. Letter-press by Haight Dudley, Kates Engraved and Printed hv The Hateh Lithographic Co., & Ponghkeepsie, N. Y. NewYorlj. AJJERICA HERAIiDICA Iniex of Colored Coats of Arms PI. Tlo. PI. No. Abereroinbie 19 1 Carpenter 16 14 Alexander 3 2 Carroll 9 2 " 17 2 Carter 20 9 Amory 4 1 Cary 9 12 " 17 1 Caverly 9 3 Anderson 5 1 Ghaloner 6 8 7 Andrews • • 6 1 Chandler 16 Appleton ••• 1 10 Chase 4 6 7 Archer • 1 3 Chauncey 6 Arnold 4 3 Chute 6 16 Bacon 9 1 Clarkson 14 8 Balche 13 10 Claytorne 9 4 Barclay 3 4 Clinton 3 7 Bard 15 6 Coddington 14 6 Barlcer 15 1 Coffin 4 4 Bartlett 15.