Blue Hills Trailside Museum Trail Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Desmodium Cuspidatum (Muhl.) Loudon Large-Bracted Tick-Trefoil

New England Plant Conservation Program Desmodium cuspidatum (Muhl.) Loudon Large-bracted Tick-trefoil Conservation and Research Plan for New England Prepared by: Lynn C. Harper Habitat Protection Specialist Massachusetts Natural Heritage and Endangered Species Program Westborough, Massachusetts For: New England Wild Flower Society 180 Hemenway Road Framingham, MA 01701 508/877-7630 e-mail: [email protected] • website: www.newfs.org Approved, Regional Advisory Council, 2002 SUMMARY Desmodium cuspidatum (Muhl.) Loudon (Fabaceae) is a tall, herbaceous, perennial legume that is regionally rare in New England. Found most often in dry, open, rocky woods over circumneutral to calcareous bedrock, it has been documented from 28 historic and eight current sites in the three states (Vermont, New Hampshire, and Massachusetts) where it is tracked by the Natural Heritage programs. The taxon has not been documented from Maine. In Connecticut and Rhode Island, the species is reported but not tracked by the Heritage programs. Two current sites in Connecticut are known from herbarium specimens. No current sites are known from Rhode Island. Although secure throughout most of its range in eastern and midwestern North America, D. cuspidatum is Endangered in Vermont, considered Historic in New Hampshire, and watch-listed in Massachusetts. It is ranked G5 globally. Very little is understood about the basic biology of this species. From work on congeners, it can be inferred that there are likely to be no problems with pollination, seed set, or germination. As for most legumes, rhizobial bacteria form nitrogen-fixing nodules on the roots of D. cuspidatum. It is unclear whether there have been any changes in the numbers or distribution of rhizobia capable of forming effective mutualisms with D. -

February 1997

MASSACHUSETTS BUTTERFLIES No. 8 February 1997 "How could you think that?... I've always been attracted by your personality.'." Copyright © 1997 – Massachusetts Butterfly Club – All rights reserved. "MASSACHUSETTS BUTTERFLIES" is the semi- annual publication of the Massachusetts Butterfly Club, a chapter of the North American Butterfly Association. Membership in NABA-MBC brings you "American Butterflies," "Massachusetts Butterflies," "The Anglewing," "Butterfly Garden News," and all of the benefits of the association and club, including field trips and meetings. Regular annual dues are $25.00. Those joining NABA-MBC for the first time should make their check payable to "NABA" and send it to our treasurer, Lyn Lovell, at the address listed below. Membership renewals are handled through the national office [NABA 4 Delaware Road Morristown, NJ 07960; telephone 201-285-09071 OFFICERS OF NABA-MASSACHUSETTS BUTTERFLY CLUB PRESIDENT - MADELINE CHAMPAGNE 7 POND AVENUE FOXBORO 02035 1508-543-3380] VlCE PRESIDENT [WEST] - DOTTIE CASE 100 BULL HILL ROAD SUNDERLAND 01375 [413-665-2941] VlCE PRESIDENT [EAST] - TOM DODD 54 BANCROFT PARK HOPEDALE 01747 [508-478-6208] SECRETARY - CATHY ASSELIN 54 BANCROFT PARK HOPEDALE 01 747 [508-478-6208] TREASURER - LYN LOVELL 198 PURCHASE STREET MILFORD 01757 [508-473-7327] "MASSACHUSETTS BUTTERFLIES" STAFF EDITOR, ETC. - BRIAN CASSlE 28 COCASSET STREET FOXBORO 02035 [508-543-3512] Articles for submission : We encourage all members to contribute to "Massachusetts Butterflies." Please send your notes, articles, and lor illustrations to Brian Cassie at the above address by the following deadlines : July 31 for the late summer issue, December 15 for the winter issue. Please send in all yearly records by November 30. -

Singletracks #41 December 1998

The Magazine of the New England Mountain Bike Association December 1998 Number 41 SSingleingleTTrackrackSS FlyingFlyingFlyingFlying HighHighHighHigh WithWithWithWith MerlinMerlinMerlinMerlin NEMBANEMBA goesgoes WWestest HotHot WinterWinter Tips!Tips! BlueBlue HillsHills MountainMountain FFestest OFF THE FRONT Howdy, Partner! artnerships are where it's at. Whether it's captain NEMBA is working closely with the equestrian group, and stoker tandemming through the forest, you the Bay State Trail Riders Association. Not only did the Pand your buds heading off to explore uncharted groups come together to ride and play a bit of poker to trails, or whether it's organizations like NEMBA teaming celebrate the new trails at Mt. Grace State Forest in up with other groups, partnerships make good things Warwick MA, but over the course of the summer they happen. also built new trail loops in Upton State Forest. Many of the misunderstandings between the horse and bike Much of this issue is about partnerships -- set were thrown out the window as they jockeyed for well, maybe not of the squeeze kind-- and position and shared the trails. There are already plans why they're good for New England trails. In for a second Hooves and Pedals, so if you missed the October, GB NEMBA's trail experts took first one, don't miss the next. leadership roles in an Appalachian Mountain Club project designed to assess NEMBA's been building many bridges over the last year, the trails of the Middlesex Fells both literally and figuratively. We're working closely Reservation. Armed with cameras and clip- with more land managers and parks than I can count boards, they led teams across the trails to and we've probably put in just as many bridges and determine the state of the dirt and to figure boardwalks! We’ve also secured $3000 of funding to out which ones needed some tender loving overhaul the map of the Lynn Woods working together care. -

Blue Hills Porphyry

AN INTEGRATED STUDY OF THE BLUE HILLS PORPHYRY AND RELATED UNITS QUINCY AND MILTON, MASSACHUSETTS by SUZANNE SAYER B. S., Tufts University SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE at the MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY August, 1974 Signature of Author Planetary .--.. ., gu s. 1974. Department of Earth and Planetar y Scienc es, August, 1974 Certified by ... ... .... .... .w o rr y~r . .. 0 -.' ,,Thesis Su i Accepted by . .... ... .. ......... ................ Chairman, Departmental Committee on Graduate Students Undgre-n - ~ N V5 1974 MIT.19 AN INTEGRATED STUDY OF THE BLUE HILLS PORPHYRY AND RELATED UNITS QUINCY AND MILTON, MASSACHUSETTS by SUZANNE SAYER Submitted to the Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in August, 1974 ABSTRACT A field and petrologic study, including two new chemical analyses and trace element determinations on three samples, was undertaken to define possible subvarieties of the Blue Hills porphyry, a member of the Blue Hills Igneous Complex. It is concluded that, the Blue Hills porphyry is geologically and mineralogically a single unit, dominantly granite porphyry, which grades into a porphyritic granite on one side. The Blue Hills porphyry becomes more aphanitic with fewer phenocrysts near the contact with the country. rocks. Textural variations correlate well with the topographic features: the higher the elevationthe more aphanitic the Blue. Hills porphyry becomes. The outcrop at the Route 128-28 intersection has traditionally been interpreted as a "fossil soil zone", but on the basis of detailed field and petrographical studies, it is reinterpreted as an extrusive facies of the Blue Hills porphyry. -

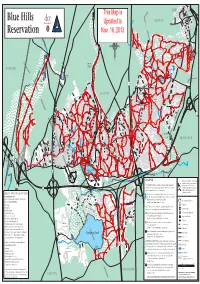

This Map Is Updated to Nov. 16, 2013

ATHLETIC 4227 FIELDS 4011 4235 LANE 4014 4133 4223 4124 ATHLETIC FIELD 4086 4085 4234 4082 4102 Dollar 4049 Lane 4166 4096 Hemenway Pond 4134 3171 Hemlock 4053 Dr 4013 3131 1214 4052 3104 Squamaug Notch Path 3174 1165 1166 3094 3024 1182 1046 3065 1217 1121 1033 1154 1122 1208 1206 3051 3085 1023 1150 1170 1210 1209 1172 1051 3040 3155 2181 1010 Closed in winter in Closed 1186 1002 2072 1045 6670 6877 1050 3090 6650 6900 2071 6880 1030 6896 6891 1001 1003 5610 5620 CONCESSION Accord Path 5600 6600 STAND 5611 1077 1057 1079 ATHLETIC FIELDS 5320 Park open dawn to dusk. 5322 5218 5380 5383 5413 5360 5216 5355 5420 ATHLETIC FIELD MAP PRINTED WITH SOY INK AND ON RECYCLED PAPER. COLORS MAY CHANGE IN BRIGHT LIGHT. 2.01 STAY ON DCR DESIGNATED TRAILS FOR SAFETY AND RESOURCE PROTECTION DCR official map printed November 2012 Printed courtesy of Trailside Museum Charitable Trust. DCR Blue Hills Reservation Proceeds to benefit Blue Hills Trailside Trail Map and Guide Museum. Enjoying the Reservation The Blue Hills Reservation Headquarters is located at 695 Hillside Street y in Milton, 1/4 mile north of Houghtons Pond, beside the State Police te ou t Station. Please stop by, or call (617) 698-1802 for further information. i o Athletic Fields v Three reservable athletic fields are available at Houghtons n the Blue Hills Reservation. d Pond. For reservations, call DCR Recreation at (617) 727-4708. i Stretching from Dedham to Quincy, Milton to Randolph, Blue Hills Trailside Museum i This DCR facility, managed by the Mass Audubon Society, the Blue Hills Reservation encompasses over 7000 acres, providing the s features cultural, historical and natural history exhibits with c a display of live wildlife of the Blue Hills. -

Blue Hills Trailside Museum

Welcome to DCR’s A World of Nature Rocky Hilltops The Faces and Places quarried in the Blue Hills have been found at sites through- out Massachusetts. The Commonwealth of Massachusetts is The scenery before you is the product of a variety of forces. With high vantage points, proximity to the Neponset Blue Hills Reservation The hilltops of the Blue Hills range offer sweeping views of named in honor of these first people of the hills. Geology, climate, soil, fires, logging, and farming have all River, easy access to the coastline and harbor islands, and an Stretching from Dedham to Quincy, and Milton to the Boston basin, the harbor, and beyond. These summits are MASSWILDLIFE · BYRNE BILL shaped the delicate harmony of land and life you see today. abundance of year-round resources, the Blue Hills have been Randolph, the Blue Hills Reservation encompasses over the remains of ancient volcanoes, which erupted 440 million ECOLOGY DCR · PUTNAM NANCY Trails traverse many habitats: rocky summits, upland and attracting people throughout the ages. Today, DCR’s Blue 7,000 acres, providing the largest open space within 35 miles years ago and then collapsed. Hikers climbing Great Blue Hill bottomland forests, meadows, swamp and pond edges, Hills Reservation is rich in both archaeological and historic of Boston. More than 120 miles of trails weave through the on the red dot trail will trace ancient lava flows that poured vernal pools, and bogs. resources. Interesting structures and other traces of our past natural fabric of forest and ponds, hilltops and wetlands. out of the volcano and quickly cooled into small crystalline The reservation supports a rich variety of native plants include artifacts of the First People, cellar holes and fruit trees Hikers can count 22 hills in the Blue Hills chain with Great rock on the surface. -

Ocm30840849-5.Pdf (2.204Mb)

XT y. rf lJ:r-, Metropolitan District Commission)nj FACILITY GUIDE A " Metropolitan Parks Centennial • 1893-1993 "Preserving the past.,, protecting the future. The Metropolitan District Commission is a unique multi-service agency with broad responsibihties for the preservation, main- tenance and enhancement of the natural, scenic, historic and aesthetic qualities of the environment within the thirty-four cit- ies and towns of metropolitan Boston. As city and town boundaries follow the middle of a river or bisect an important woodland, a metropolitan organization that can manage the entire natural resource as a single entity is essential to its protec- tion. Since 1893, the Metropolitan District Com- mission has preserved the region's unique resources and landscape character by ac- quiring and protecting park lands, river corridors and coastal areas; reclaiming and restoring abused and neglected sites and setting aside areas of great scenic beauty as reservations for the refreshment, recrea- tion and health of the region's residents. This open space is connected by a network Charles Eliot, the principle of landscaped parkways and bridges that force behind today's MDC. are extensions of the parks themselves. The Commission is also responsible for a scape for the enjoyment of its intrinsic val- vast watershed and reservoir system, ues; providing programs for visitors to 120,000 acres of land and water resources, these properties to encourage appreciation that provides pure water from pristine and involvment with their responsible use, areas to 2.5 million people. These water- providing facilities for active recreation, shed lands are home to many rare and en- healthful exercise, and individual and dangered species and comprise the only team athletics; protecting and managing extensive wilderness areas of Massachu- both public and private watershed lands in setts. -

Great Blue Hill, Erosion in This Area? Maintaining Trails on Soil and Helping Control Insects and Disease

Welcome to the soil in place and minimizing erosion to healthy and productive by ridding the forest the trail. Can you see any signs of runoff and floor of dead wood, returning nutrients to the 5. PINING FOR M ORE Great Blue Hill, erosion in this area? Maintaining trails on soil and helping control insects and disease. Take a look at the trees around you. the highest point in the 7000 acre Blue Hills slopes is a challenge. Please help the DCR Sadly, most forest fires in the northeast are Here three pines mingle along the Reservation and the highest coastal elevation park rangers by staying on the marked trail caused by humans, from carelessly discarding rocky slope. Can you find them? along the Atlantic seaboard south of Maine. and not creating shortcuts. matches and cigarettes. Remember, please be White pine, the Blue Hills This large dome of granite measures 635 feet careful with fire in the forest. most common evergreen, at the summit. Hikers will be rewarded with has soft and pliable needles TAKEN FOR GRANITE a spectacular view of the surrounding 2. in bundles of five. Now look countryside. Feel the exposed rock underfoot and along CAUTION for a tree with needles in The summit road is ahead. the trail. You are now stepping on rocks bundles of two and thick Please use caution as you cross reddish bark. The red pine is named for its Before you begin… which once oozed from ancient volcanoes the paved road. Be aware of Your hike up and down Great Blue will take millions of years ago. -

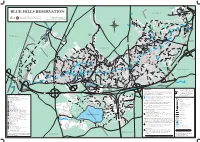

Blue Hills Reservation Fields

ATHLETIC 4227 BLUE HILLS RESERVATION FIELDS 4011 4235 LANE 4014 4133 4223 4124 ATHLETIC FIELD 4086 4085 4234 4082 4102 Dollar 4049 Lane 4166 4096 Hemenway Pond 4134 3171 Hemlock 4053 Dr 4013 3131 1214 4052 3104 Squamaug Notch Path 3174 1165 1166 3094 3024 1182 1046 3065 1217 1121 1033 1154 1122 1208 1206 3051 3085 1023 1150 1170 1210 1209 1172 1051 3040 3155 2181 1010 Closed in winter in Closed 1186 1002 2072 1045 6670 6877 1050 3090 6650 6900 2071 6880 1030 6896 6891 1001 1003 5610 5620 CONCESSION Accord Path 5600 6600 STAND 5611 1077 1057 1079 LEGEND Intersection Marker: The four digit ATHLETIC FIELDS numbers seen on the map designate DESTINATION TRAILS are marked with rectangles and are designed trail intersections. Look for the for much longer and more strenuous day hikes. These are not loop trails corresponding white wooden signs so plan transportation back to your starting point. with black numbers on trees or posts along the trails. 5320 RULES AND REGULATIONS Blue rectangles mark the popular Skyline which traverses the entire 5322 Park open dawn to dusk. Blue Hills Range with many fantastic views. Note the north and south For the protection and enjoyment of the Blue Hills, branches in the western part of the reservation. Reservation Headquarters the following are prohibited: Length: 9 miles Hiking Time: 4 to 7 hours Littering 5218 Parking LOOP TRAILS are marked with dots. Loop trails begin and end at the Open fires 5380 same point at designated parking areas as marked on the map. Canoe Launch Metal detectors Alcoholic beverages Green dots mark several woodland loops which allow you to enjoy Restrooms (seasonal only) Pets, except on a leash the natural beauty of the reservation. -

White Liners Endure Stormy Season

The Newsletter of the Southeastern Chapter of the Appalachian Mountain Club I April 2017 Get SEM activities delivered right to your email inbox! Sign up for the AMC Activity Digest. email [email protected] Or call 1-800-372-1758 Find past issues of The Southeast Breeze on our website. Like us on Facebook Follow us on Twitter Have a story for The Southeast Breeze? Pat Achorn presents Bill Doherty with his White Lining patch at the quay overlooking Please send your Word doc Ponkapoag Pond. Photo by Paul Brookes and photographs to [email protected]. White Liners Endure Stormy Season Please send photos as Written by Paul Brookes, Hiking Leader separate attachments, including Our second annual season of White Lining the Blue Hills has sadly come to a the name of each close. We met weekly Tuesday mornings and hiked in the Blue Hills during the photographer. Include the winter months from the Winter Solstice to the Spring Equinox. words “Breeze Article” in the subject line. Although in general the winter was mild, the few storms that we did have arrived on Shop the Breeze Market precisely the wrong days, forcing us to cancel three of the twelve hikes. The first for equipment bargains! cancellation was at the trailhead. Only the leaders and three other people turned out, which just shows that the majority can be wiser than the few. I and three hardy Members looking to sell, trade, or free-cycle their used souls did an informal hike through horizontal rain for a couple of hours before equipment can post for free. -

Metropolitan District Commission Reservations and Facilities Guide

s 2- / (Vjjh?- e^qo* • M 5 7 UMASS/AMHERST A 31E0bt,01t3b0731b * Metropolitan District Commission Reservations and Facilities Guide MetroParks MetroParkways MetroPoRce PureWater 6 Table of Contents OPEN SPACE - RESERVATIONS Beaver Brook Reservation 2 Belle Isle Marsh Reservation 3 Blue Hills Reservation 4 Quincy Quarries Historic Site 5 Boston Harbor Islands State Park 6-7 Breakheart Reservation 8 Castle Island 9 Charles River Reservation 9-11 Lynn/Nahant Beach Reservation 12 Middlesex Fells Reservation 13 Quabbin Reservoir 14 Southwest Corridor Park 15 S tony Brook Reserv ation 1 Wollaston Beach Reservation 17 MAP 18-19 RECREATIONAL FACILITIES Bandstands and Music Shells 21 Beaches 22 Bicycle Paths 23 Boat Landings/Boat Launchings 23 Camping 24 Canoe Launchings 24 Canoe Rentals 24 Fishing 25 Foot Trails and Bridle Paths 26 Golf Courses 26 Museums and Historic Sites 27 Observation Towers 27 Pedestrian Parks 28 Running Paths 28 Sailing Centers 28 Skiing Trails 29 Skating Rinks 30-31 Swimming Pools 32-33 Tennis Courts 34 Thompson Ctr. for the Handicapped 35 Zoos 35 Permit Information 36 GENERAL INFORMATION 37 Metropolitan District Commission Public Information Office 20 Somerset Street, Boston, MA 02108 (617) 727-5215 Open Space... Green rolling hills, cool flowing rivers, swaying trees, crisp clean air. This is what we imagine when we think of open space. The Metropolitan District Commission has been committed to this idea for over one hundred years. We invite you to enjoy the many open spaces we are offering in the metropolitan Boston area. Skiing in the Middlesex Fells Reservation, sailing the Charles River, or hiking at the Blue Hills are just a few of the activities offered. -

April – June 2012 Volume 37, Number 2

FRIENDS OF THE BLUE HILLS PROTECT & PRESERVE April – June 2012 Volume 37, Number 2 As Incidence of Lyme Disease Increases, More Blue Hills Visitors at Risk After contracting Lyme disease last fall, tell-tale bulls eye red mark Westwood resident Elaine worries about that surrounds the bite of getting sick if she returns to the Blue an infected tick bite and her Hills. While we all can still enjoy the Blue doctor prescribed antibiotics Hills, Elaine’s story will become ever more that healed her. common as the incidence of Lyme disease She is back to her regular continues to climb. A neighborhood that activities now but is reluc- borders the Reservation reports that 30 tant to return to the park households have 30 incidents of Lyme because she is concerned disease. We need to work together to make about getting so sick again. sure Elaine and everyone who loves the Knowing she couldn’t help Blue Hills can continue to enjoy it. control Lyme disease by herself, she contacted the This is not your grandparents’ Blue Hills. When many of us were growing up, most people had never heard of Lyme laine Kerrigan used to love Friends of the Blue Hills disease. Now almost everyone knows someone who’s had it. Ehiking in the Blue Hills. and discovered that she’s not Elaine Kerrigan is one of them. Though she has lived her whole alone. Many people who visit the Reservation want we can work together to reduce the risk life in Weymouth, just 10 minutes to protect themselves and their families of Lyme disease and protect the for- away from the park, she didn’t start from Lyme disease and its potentially ests so that all visitors feel comfortable exploring here until she was in her devastating effects.