RP19-01 Moose Pass

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Conferences, Workshops, Seminars, Special Events

**Marks new items in this issue February 12, 2020 Compiled weekly by Peg Tileston on behalf of Trustees for Alaska, The Alaska Center, and The Alaska Conservation Foundation. CONFERENCES, WORKSHOPS, SEMINARS, SPECIAL EVENTS SPRING 2020 SUSTAINABLE ENERGY ONLINE CLASSES, BRISTOL BAY is offered through the UAF-Bristol Bay Sustainable Energy program. April 1 to April 29 - SMALL WIND ENERGY SYSTEMS, ENVI F150, 1-cr, 5 wks., 5:20 to 8pm, CRN 37949 May 8 – 10 - ENERGY EFFICIENT BUILDING DESIGN AND SIMULATION, ENVI F122, 1-cr 3 days, CRN TBD For more info contact Mark Masteller, Asst. Prof. Sustainable Energy, at 907-414-0198 or email [email protected]. February 20 – April 30 WASILLA - GARDENING CLASS SERIES will be held in the Wasilla Museum and Visitor Center from 6:30 to 8:30pm on the following dates: February 20 - Learn how to heal your landscape and create a cultivated ecology. We have been using regenerative theory in our home garden for a long time. We are applying regenerative theory to our Market Farm and the gains are enormous. March 5 - Explore Edible Landscaping for Alaska! This class provides simple and effective design tools on how to create growing spaces throughout your home layout. Using traditional landscaping techniques coupled with a Permaculture flair- learn how create, design and implement spaces that are both functional and beautiful. Taking our Permaculture Design for Growing Spaces is recommended but not required. March 19 - How to balance your soil so that you can reap the rewards of the spring sow. Learn all the regenerative practices for caring for your soil. -

Be Properly 'Armed' Before Doing 'Combat' on Upper Kenai

Refuge Notebook • Vol. 1, No. 14 • June 11, 1999 Be properly ‘armed’ before doing ‘combat’ on upper Kenai by Bill Kent The 15 miles of the Kenai River upstream from Ski- costs $5, which covers parking for one vehicle. lak Lake, known as the upper Kenai River, will open Boaters usually put in at the Kenai River Bridge for fishing today. Many people know this area pri- in Cooper Landing, just below Kenai Lake and at the marily for the “combat” fishing at the confluence of ferry. Jim’s Landing is the last takeout before the Ke- the Russian and Kenai Rivers and may not think about nai Canyon. If you pass Jim’s Landing, the next take this portion of the river the same way as the lower out is Upper Skilak Lake campground. Please note that reaches below Skilak Lake. However there are differ- Jim’s Landing is closed to fishing. ences and similarities you should keep in mind when The riverbanks of the Upper Kenai are just as frag- visiting this part of Kenai National Wildlife Refuge. ile as the banks below Skilak Lake. Riverbank fishing Everyone fishing the Upper Kenai should review closures are scattered along the river from the bride at the state fishing regulations carefully. There are re- Kenai Lake to Jim’s Landing. These areas are posted strictions on harvest limits, types of gear, and area clo- “Closed” with Fish and Game or refuge signs and are sures which are unique to this area. described in the fishing regulations. For instance, no rainbow trout may be harvested The thousands of visitors who use the upper Kenai there, in keeping with the management strategy de- can generate a great deal of litter and trash. -

Chugach National Forest Wilderness Area Inventory and Evaluation

Chugach National Forest Wilderness Area Inventory and Evaluation Overview of the Wilderness Area Recommendation Process As part of plan revision, the responsible official, the forest supervisor, shall “identify and evaluate lands that may be suitable for inclusion in the National Wilderness Preservation System and determine whether to recommend any such lands for wilderness designation” (36 CFR 219.7(c)(2)(v), effective May 9, 2012). Forest Service directives (FSH 1909.12, Chapter 70) for implementing the 2012 Planning Rule provide further guidance on how to complete this process in four steps: (1) Identify and inventory all lands that may be suitable for inclusion in the National Wilderness Preservation System (2) Evaluate the wilderness characteristics of each area based on a given set of criteria (3) The forest supervisor will determine which areas to further analyze in the NEPA process (4) The forest supervisor will decide which areas, if any, to recommend for inclusion in the National Wilderness Preservation System This report provides documentation for the inventory and evaluation steps of this process, and is divided into two sections. The first section provides information about the inventory process and results. These results also include a description of the current conditions and management for vegetation, wildlife, fish, recreation, and access to the Chugach National Forest as they are related to wilderness character. This description is intended to provide a big-picture view of national forest resources and serve as a foundation for the evaluation section. The second section provides an area by area evaluation of wilderness characteristics found in the inventoried lands. -

Chugach National Forest 2016 Visitor Guide

CHUGACH NATIONAL FOREST 2016 VISITOR GUIDE CAMPING WILDILFE VISITOR CENTERS page 10 page 12 page 15 Welcome Get Out and Explore! Hop on a train for a drive-free option into the Chugach National Forest, plan a multiple day trip to access remote to the Chugach National Forest! primitive campsites, attend the famous Cordova Shorebird Festival, or visit the world-class interactive exhibits Table of Contents at Begich, Boggs Visitor Center. There is something for everyone on the Chugach. From the Kenai Peninsula to The Chugach National Forest, one of two national forests in Alaska, serves as Prince William Sound, to the eastern shores of the Copper River Delta, the forest is full of special places. Overview ....................................3 the “backyard” for over half of Alaska’s residents and is a destination for visi- tors. The lands that now make up the Chugach National Forest are home to the People come from all over the world to experience the Chugach National Forest and Alaska’s wilderness. Not Eastern Kenai Peninsula .......5 Alaska Native peoples including the Ahtna, Chugach, Dena’ina, and Eyak. The only do we welcome international visitors, but residents from across the state travel to recreate on Chugach forest’s 5.4 million acres compares in size with the state of New Hampshire and National Forest lands. Whether you have an hour or several days there are options galore for exploring. We have Prince William Sound .............7 comprises a landscape that includes portions of the Kenai Peninsula, Prince Wil- listed just a few here to get you started. liam Sound, and the Copper River Delta. -

Please Call TOWER ROCK LODGE When You Arrive in Anchorage 1

Please Call TOWER ROCK LODGE What is included? When You Arrive in Anchorage All necessary equipment including all tackle, bait, flies, Orvis #8 fly rods 1-800-284-3474 and spinning gear and Loomis salmon rods with Shimano Dakota reels. GRUDGEON rain gear and Orvis hip Destination Kenai Peninsula waders Secluded bank fishing in front of Situated near the town of Soldotna, in Tower Rock Lodge for Silvers and south-central Alaska, TOWER ROCK LODGE Reds. Excellent opportunities. 1 800 284 FISH (3474) is an internationally One 50 # wet lock box for your recognized five star full service lodge catch, for most package plans located 12 miles upriver on the banks of the All meals (advance notice for special world famous Kenai River. Upon arrival, dietary needs please) and please check in at the Orvis Dining Hall. complimentary beverages and wine Arriving in Anchorage Check YOUR Checklist! Drive from Anchorage airport 147 You will need to obtain your fishing miles (3-1/2 hours) along the scenic license and King Salmon stamp (if Seward Highway thru the Chugach applicable) covering the amount of Mountains to the town of Soldotna days you plan to fish (1, 3, 7, 14 days and TOWER ROCK LODGE and annually). Fly EVA Aviation 800 478 1947 www.admin.adfg.state.ak.us/license/ www.flyera.com to Kenai Airport or at any local convenience store. (flight time 25 minutes), pick up Plan your clothing around a layering your rental car and drive directly to system that adjusts to changing TOWER ROCK LODGE which is only temps and conditions. -

Recall Retail List 030-2020

United States Food Safety Department of and Inspection Agriculture Service RETAIL CONSIGNEES FOR FSIS RECALL 030-2020 FSIS has reason to believe that the following retail location(s) received LEAN CUISINE Baked Chicken meal products that have been recalled by Nestlé Prepared Foods. This list may not include all retail locations that have received the recalled productor may include retail locations that did not actually receive the recalled product. Therefore, it is important that you use the product-specific identification information, available at https://www.fsis.usda.gov/wps/portal/fsis/topics/recalls-and-public- health-alerts/recall-case-archive/archive/2020/recall-030-2020-release, in addition to this list of retail stores, to check meat or poultry products in your possession to see if they have been recalled. Store list begins on next page United States Food Safety USDA Department of And Inspection - Agl'iculture Service Retail List for Recall Number: 030-2020 chicken meal product List Current As Of: 26-Jan-21 Nationwide, State-Wide, or Area-Wide Distribution Retailer Name Location 1 Albertsons AZ, CA, LA, NV, OR, TX, WA 2 Bashas AZ 3 Big Y CT 4 City Market CO 5 Dillons KS 6 Food Lion GA, SC, TN, VA 7 Fred Meyer OR, WA 8 Fry's Food And Drug AZ 9 Fry's Marketplace AZ 10 Gelson's Market CA 11 Giant MD, PA, VA 12 Giant Eagle Supermarket OH, PA 13 Heinen's OH 14 Hy-Vee IL, IA, KS, MN, MO, NE, SD 15 Ingles Markets GA, NC, SC, TN 16 Jay C IN 17 JewelOsco IL 18 King Soopers CO AR, GA, IL, IN, KY, MI, MS, OH, SC, TN, TX, VA, 19 Kroger WV 20 Lowes NC 21 Marianos IL 22 Meijers IL, IN, MI 23 Pavilions CA 24 Pick n Save WI 25 Piggly Wiggly WI 26 Publix FL, GA Page 1 of 85 Nationwide, State-Wide, or Area-Wide Distribution Retailer Name Location 27 Quality Food Center WA 28 Ralphs CA 29 Ralphs Fresh Fare CA 30 Randalls TX 31 Safeway AZ, CA, HI, OR, WA 32 Shaw's MA, NH 33 Smart & Final CA 34 Smith's NV, NM, UT 35 Stater Bros. -

Kenai Peninsula Area – Units 7 & 15

Kenai Peninsula Area – Units 7 & 15 PROPOSAL 156 - 5 AAC 85.045. Hunting seasons and bag limits for moose. Shorten the moose seasons in Unit 15 as follows: Go back to a September season, with the archery season starting on September 1, running for one week with a two week rifle season following. What is the issue you would like the board to address and why? Moose hunting starts too early. The weather is too warm. Antler restrictions due to lack of bulls. Shorten the season. Three weeks rather than six is plenty of moose hunting opportunity considering the lack of mature bulls. There will be better meat and less spoilage. Antlers are still growing in archery season. Hunters will need to butcher moose the day they are harvested. PROPOSED BY: Joseph Ross (EG-C14-193) ****************************************************************************** PROPOSAL 157 - 5 AAC 85.045. Hunting seasons and bag limits for moose. Change the general bull moose season dates in Unit 15 to September 1-30 as follows: Move the season forward ten days, changing the Unit 15 general bull moose harvest dates to September 1-30, so a much higher percentage of harvested meat will make it back to hunters' homes to be good table fare. What is the issue you would like the board to address and why? At issue is the preservation of moose meat in Unit 15. It is so warm and humid during the season that moose harvests can turn into monumental struggles to properly care for fresh meat. The culprits are heat, moisture, and flies, each singularly able to ruin a harvest in a matter of a day or two. -

Erosion and Sedimentation in the Kenai River, Alaska

ay) ifim Erosion and Sedimentation in the Kenai River, Alaska By KEVIN M. SCOTT GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 1235 Prepared in cooperation with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1982 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR JAMES G. WATT, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Dallas L. Peck, Director Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Scott/ Kevin M./ 1935- Erosion and sedimentation in the Kenai River/ Alaska. (Geological Survey professional paper ; 1235) Bibliography: p. 33-35 Supt. of Docs, no.: I 19.16:1235 1. Sediments (Geology) Alaska Kenai River watershed. 2. Erosion Alaska Kenai River watershed. I. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. II. Title. III. Series: United States. Geological Survey Professional Paper 1235. QE571.S412 553.7'8'097983 81-6755 AACR2 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402 CONTENTS Page Page Abstract _-_----___---_-______________________________ 1 Bed material Continued Introduction __________________________________________ 1 Gravel dunes in channel below SkilakLake ___-----_-___- 17 The Kenai River watershed -_-------_---__--_____________ 3 Armoring of the channel _---____------------_-_-----_ 18 Climate ____________________________________ 3 Possible effects of armoring on salmon habitat ___________ 19 Vegetation ________________________________________ 3 Surficial deposits of the modern flood plain _____________ 19 Hydrology ____________________________________________ 4 Suspended sediment -

Fishing in the Seward Area

Southcentral Region Department of Fish and Game Fishing in the Seward Area About Seward The Seward and North Gulf Coast area is located in the southeastern portion of Alaska’s Kenai Peninsula. Here you’ll find spectacular scenery and many opportunities to fish, camp, and view Alaska’s wildlife. Many Seward area recreation opportunities are easily reached from the Seward Highway, a National Scenic Byway extending 127 miles from Seward to Anchorage. Seward (pop. 2,000) may also be reached via railroad, air, or bus from Anchorage, or by the Alaska Marine ferry trans- portation system. Seward sits at the head of Resurrection Bay, surrounded by the U.S. Kenai Fjords National Park and the U.S. Chugach National Forest. Most anglers fish salt waters for silver (coho), king (chinook), and pink (humpy) salmon, as well as halibut, lingcod, and various species of rockfish. A At times the Division issues in-season regulatory changes, few red (sockeye) and chum (dog) salmon are also harvested. called Emergency Orders, primarily in response to under- or over- King and red salmon in Resurrection Bay are primarily hatch- abundance of fish. Emergency Orders are sent to radio stations, ery stocks, while silvers are both wild and hatchery stocks. newspapers, and television stations, and posted on our web site at www.adfg.alaska.gov . A few area freshwater lakes have stocked or wild rainbow trout populations and wild Dolly Varden, lake trout, and We also maintain a hot line recording at (907) 267- 2502. Or Arctic grayling. you can contact the Anchorage Sport Fish Information Center at (907) 267-2218. -

Wild Resource Harvests and Uses by Residents of Seward and Moose Pass, Alaska, 2000

Wild Resource Harvests and Uses by Residents of Seward and Moose Pass, Alaska, 2000 By Brian Davis, James A. Fall, and Gretchen Jennings Technical Paper Number 271 Prepared for: Chugach National Forest US Forest Service 3301 C Street, Suite 300 Anchorage, AK 9950s Purchase Order No. 43-0109-1-0069 Division of Subsistence Alaska Department of Fish and Game Juneau, Alaska June 2003 ADA PUBLICATIONS STATEMENT The Alaska Department of Fish and Game operates all of its public programs and activities free from discrimination on the basis of sex, color, race, religion, national origin, age, marital status, pregnancy, parenthood, or disability. For information on alternative formats available for this and other department publications, please contact the department ADA Coordinator at (voice) 907-465-4120, (TDD) 1-800-478-3548 or (fax) 907-586-6595. Any person who believes she or he has been discriminated against should write to: Alaska Department of Fish and Game PO Box 25526 Juneau, AK 99802-5526 or O.E.O. U.S. Department of the Interior Washington, D.C. 20240 ABSTRACT In March and April of 2001 researchers employed by the Alaska Department of Fish and Game’s (ADF&G) Division of Subsistence conducted 203 interviews with residents of Moose Pass and Seward, two communities in the Kenai Peninsula Borough. The study was designed to collect information about the harvest and use of wild fish, game, and plant resources, demography, and aspects of the local cash economy such as employment and income. These communities were classified “non-rural” by the Federal Subsistence Board in 1990, which periodically reviews its classifications. -

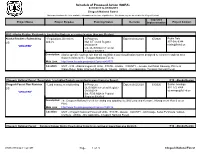

Schedule of Proposed Action (SOPA) 07/01/2019 to 09/30/2019 Chugach National Forest This Report Contains the Best Available Information at the Time of Publication

Schedule of Proposed Action (SOPA) 07/01/2019 to 09/30/2019 Chugach National Forest This report contains the best available information at the time of publication. Questions may be directed to the Project Contact. Expected Project Name Project Purpose Planning Status Decision Implementation Project Contact R10 - Alaska Region, Regionwide (excluding Projects occurring in more than one Region) Alaska Roadless Rulemaking - Regulations, Directives, In Progress: Expected:06/2020 07/2020 Robin Dale EIS Orders NOI in Federal Register 907-586-9344 [email protected] *UPDATED* 08/02/2018 Est. DEIS NOA in Federal Register 07/2019 Description: Alaska specific roadless rule that will establish a land classification system designed to conserve roadless area characteristics on the Tongass National Forest. Web Link: http://www.fs.usda.gov/project/?project=54511 Location: UNIT - R10 - Alaska Region All Units. STATE - Alaska. COUNTY - Juneau, Ketchikan Gateway, Prince of Wales-Outer, Sitka, Wrangell-Petersburg, Yakutat. LEGAL - Not Applicable. Tongass National Forest. Chugach National Forest, Forestwide (excluding Projects occurring in more than one Forest) R10 - Alaska Region Chugach Forest Plan Revision - Land management planning In Progress: Expected:02/2020 03/2020 Susan Jennings EIS DEIS NOA in Federal Register 907-772-5864 [email protected] *UPDATED* 08/03/2018 Est. FEIS NOA in Federal Register 09/2019 Description: The Chugach National Forest is revising and updating its 2002 Land and Resource Management Plan (Forest Plan). Web Link: http://www.fs.usda.gov/project/?project=40816 Location: UNIT - Chugach National Forest All Units. STATE - Alaska. COUNTY - Anchorage, Kenai Peninsula, Valdez- Cordova. LEGAL - Not Applicable. Chugach National Forest. -

Kenai Winter Access

Kenai Winter Access United States Record of Decision Department of Agriculture Forest Service Chugach National Forest R10-MB-596 July 2007 "The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, disability, and where applicable, sex, marital status, familial status, parental status, religion, sexual orientation, genetic information, political beliefs, reprisal, or because all or part of an individual’s income is derived from any public assistance program. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA's TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TDD). To file a complaint of discrimination, write to USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, 1400 Independence Avenue, S.W., Washington, DC 20250-9410, or call (800) 795-3272 (voice) or (202) 720-6382 (TDD). USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer.” Kenai Winter Access Record of Decision USDA Forest Service, Region 10 Chugach National Forest Seward Ranger District This Record of Decision (ROD) documents my decision concerning winter access on the Seward Ranger District. I have selected the Modified Preferred Alternative described in the Kenai Winter Access Final Environmental Impact Statement (FEIS). Through this decision I am also approving a non-significant amendment to the Chugach National Forest Revised Land and Resource Management Plan of 2002 (Forest Plan). This decision is based upon: the FEIS, the Forest Plan, the Forest Plan Record of Decision (ROD), and the FEIS for the Forest Plan.