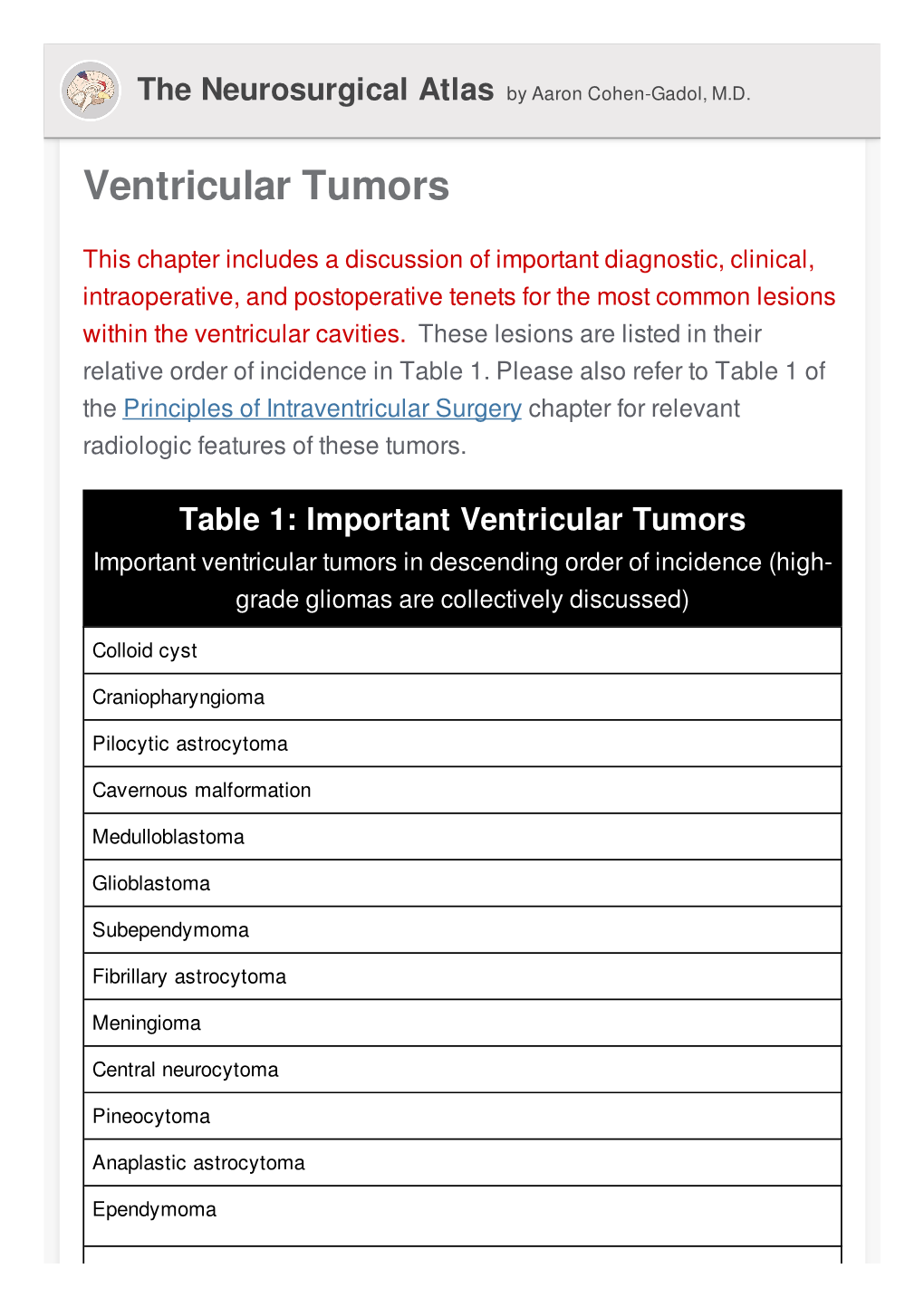

Ventricular Tumors

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Intraventricular Neuroepithelial Tumors: Surgical Outcome, Technical Considerations and Review of Literature A

Aftahy et al. BMC Cancer (2020) 20:1060 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-020-07570-1 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Intraventricular neuroepithelial tumors: surgical outcome, technical considerations and review of literature A. Kaywan Aftahy1* , Melanie Barz1, Philipp Krauss1, Friederike Liesche2, Benedikt Wiestler3, Stephanie E. Combs4,5,6, Christoph Straube4, Bernhard Meyer1 and Jens Gempt1 Abstract Background: Intraventricular neuroepithelial tumors (IVT) are rare lesions and comprise different pathological entities such as ependymomas, subependymomas and central neurocytomas. The treatment of choice is neurosurgical resection, which can be challenging due to their intraventricular location. Different surgical approaches to the ventricles are described. Here we report a large series of IVTs, its postoperative outcome at a single tertiary center and discuss suitable surgical approaches. Methods: We performed a retrospective chart review at a single tertiary neurosurgical center between 03/2009–05/ 2019. We included patients that underwent resection of an IVT emphasizing on surgical approach, extent of resection, clinical outcome and postoperative complications. Results: Forty five IVTs were resected from 03/2009 to 05/2019, 13 ependymomas, 21 subependymomas, 10 central neurocytomas and one glioependymal cyst. Median age was 52,5 years with 55.6% (25) male and 44.4% (20) female patients. Gross total resection was achieved in 93.3% (42/45). 84.6% (11/13) of ependymomas, 100% (12/21) of subependymomas, 90% (9/10) of central neurocytomas and one glioependymal cyst were completely removed. Postoperative rate of new neurological deficits was 26.6% (12/45). Postoperative new permanent cranial nerve deficits occurred in one case with 4th ventricle subependymoma and one in 4th ventricle ependymoma. -

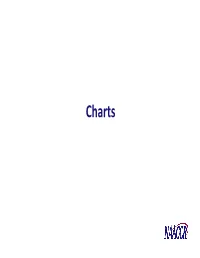

Charts Chart 1: Benign and Borderline Intracranial and CNS Tumors Chart

Charts Chart 1: Benign and Borderline Intracranial and CNS Tumors Chart Glial Tumor Neuronal and Neuronal‐ Ependymomas glial Neoplasms Subependymoma Subependymal Giant (9383/1) Cell Astrocytoma(9384/1) Myyppxopapillar y Desmoplastic Infantile Ependymoma Astrocytoma (9412/1) (9394/1) Chart 1: Benign and Borderline Intracranial and CNS Tumors Chart Glial Tumor Neuronal and Neuronal‐ Ependymomas glial Neoplasms Subependymoma Subependymal Giant (9383/1) Cell Astrocytoma(9384/1) Myyppxopapillar y Desmoplastic Infantile Ependymoma Astrocytoma (9412/1) (9394/1) Use this chart to code histology. The tree is arranged Chart Instructions: Neuroepithelial in descending order. Each branch is a histology group, starting at the top (9503) with the least specific terms and descending into more specific terms. Ependymal Embryonal Pineal Choro id plexus Neuronal and mixed Neuroblastic Glial Oligodendroglial tumors tumors tumors tumors neuronal-glial tumors tumors tumors tumors Pineoblastoma Ependymoma, Choroid plexus Olfactory neuroblastoma Oligodendroglioma NOS (9391) (9362) carcinoma Ganglioglioma, anaplastic (9522) NOS (9450) Oligodendroglioma (9390) (9505 Olfactory neurocytoma Ganglioglioma, malignant (()9521) anaplastic (()9451) Anasplastic ependymoma (9505) Olfactory neuroepithlioma Oligodendroblastoma (9392) (9523) (9460) Papillary ependymoma (9393) Glioma, NOS (9380) Supratentorial primitive Atypical EdEpendymo bltblastoma MdllMedulloep ithliithelioma Medulloblastoma neuroectodermal tumor tetratoid/rhabdoid (9392) (9501) (9470) (PNET) (9473) tumor -

Central Nervous System Tumors General ~1% of Tumors in Adults, but ~25% of Malignancies in Children (Only 2Nd to Leukemia)

Last updated: 3/4/2021 Prepared by Kurt Schaberg Central Nervous System Tumors General ~1% of tumors in adults, but ~25% of malignancies in children (only 2nd to leukemia). Significant increase in incidence in primary brain tumors in elderly. Metastases to the brain far outnumber primary CNS tumors→ multiple cerebral tumors. One can develop a very good DDX by just location, age, and imaging. Differential Diagnosis by clinical information: Location Pediatric/Young Adult Older Adult Cerebral/ Ganglioglioma, DNET, PXA, Glioblastoma Multiforme (GBM) Supratentorial Ependymoma, AT/RT Infiltrating Astrocytoma (grades II-III), CNS Embryonal Neoplasms Oligodendroglioma, Metastases, Lymphoma, Infection Cerebellar/ PA, Medulloblastoma, Ependymoma, Metastases, Hemangioblastoma, Infratentorial/ Choroid plexus papilloma, AT/RT Choroid plexus papilloma, Subependymoma Fourth ventricle Brainstem PA, DMG Astrocytoma, Glioblastoma, DMG, Metastases Spinal cord Ependymoma, PA, DMG, MPE, Drop Ependymoma, Astrocytoma, DMG, MPE (filum), (intramedullary) metastases Paraganglioma (filum), Spinal cord Meningioma, Schwannoma, Schwannoma, Meningioma, (extramedullary) Metastases, Melanocytoma/melanoma Melanocytoma/melanoma, MPNST Spinal cord Bone tumor, Meningioma, Abscess, Herniated disk, Lymphoma, Abscess, (extradural) Vascular malformation, Metastases, Extra-axial/Dural/ Leukemia/lymphoma, Ewing Sarcoma, Meningioma, SFT, Metastases, Lymphoma, Leptomeningeal Rhabdomyosarcoma, Disseminated medulloblastoma, DLGNT, Sellar/infundibular Pituitary adenoma, Pituitary adenoma, -

Seizure Prognosis of Patients with Low-Grade Tumors

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector Seizure 21 (2012) 540–545 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Seizure jou rnal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/yseiz Seizure prognosis of patients with low-grade tumors a b,c c,d c,e Cynthia A. Kahlenberg , Camilo E. Fadul , David W. Roberts , Vijay M. Thadani , c,e a,f c,e, Krzysztof A. Bujarski , Rod C. Scott , Barbara C. Jobst * a Dartmouth College, Hanover, NH, United States b Sections of Hematology, Oncology and Neurology, Dartmouth Hitchcock Medical Center, Lebanon, NH, United States c Dartmouth Medical School, Hanover, NH, United States d Section of Neurosurgery, Department of Surgery, Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center, Lebanon, NH, United States e Department of Neurology, Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center, Lebanon, NH, United States f Neurosciences Unit, Institute of Child Health, University College London, Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children NHS Trust, London, UK A R T I C L E I N F O A B S T R A C T Article history: Purpose: Seizures frequently impact the quality of life of patients with low grade tumors. Management is Received 12 January 2012 often based on best clinical judgment. We examined factors that correlate with seizure outcome to Received in revised form 24 May 2012 optimize seizure management. Accepted 24 May 2012 Methods: Patients with supratentorial low-grade tumors evaluated at a single institution were retrospectively reviewed. Using multiple regression analysis the patient characteristics and treatments Keywords: were correlated with seizure outcome using Engel’s classification. -

Clinical, Radiological, and Pathological Features in 43 Cases of Intracranial Subependymoma

CLINICAL ARTICLE J Neurosurg 122:49–60, 2015 Clinical, radiological, and pathological features in 43 cases of intracranial subependymoma Zhiyong Bi, MD, Xiaohui Ren, MD, Junting Zhang, MD, and Wang Jia, MD Neurosurgery, Beijing Tiantan Hospital, Capital Medical University, Beijing, China ObjECT Intracranial subependymomas are rarely reported due to their extremely low incidence. Knowledge about sub- ependymomas is therefore poor. This study aimed to analyze the incidence and clinical, radiological, and pathological features of intracranial subependymomas. METHodS Approximately 60,000 intracranial tumors were surgically treated at Beijing Tiantan Hospital between 2003 and 2013. The authors identified all cases in which patients underwent resection of an intracranial tumor that was found to be pathological examination demonstrated to be subependymoma and analyzed the data from these cases. RESULTS Forty-three cases of pathologically confirmed, surgically treated intracranial subependymoma were identi- fied. Thus in this patient population, subependymomas accounted for approximately 0.07% of intracranial tumors (43 of an estimated 60,000). Radiologically, 79.1% (34/43) of intracranial subependymomas were misdiagnosed as other dis- eases. Pathologically, 34 were confirmed as pure subependymomas, 8 were mixed with ependymoma, and 1 was mixed with astrocytoma. Thirty-five patients were followed up for 3.0 to 120 months after surgery. Three of these patients expe- rienced tumor recurrence, and one died of tumor recurrence. Univariate analysis revealed that shorter progression-free survival (PFS) was significantly associated with poorly defined borders. The association between shorter PFS and age < 14 years was almost significant (p = 0.51), and this variable was also included in the multivariate analysis. -

Genomic Landscape of Intramedullary Spinal Cord Gliomas Ming Zhang1,10, Rajiv R

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Genomic Landscape of Intramedullary Spinal Cord Gliomas Ming Zhang1,10, Rajiv R. Iyer2,10, Tej D. Azad2,3,10, Qing Wang1, Tomas Garzon-Muvdi2,4, Joanna Wang5, Ann Liu2, Peter Burger6, Charles Eberhart6, Fausto J. Rodriguez 6, Daniel M. Sciubba2, Jean-Paul Wolinsky2,7, Ziya Gokaslan2,8, Mari L. Groves2, George I. Jallo2,9* & Chetan Bettegowda1,2* Intramedullary spinal cord tumors (IMSCTs) are rare neoplasms that have limited treatment options and are associated with high rates of morbidity and mortality. To better understand the genetic basis of these tumors we performed whole exome sequencing on 45 tumors and matched germline DNA, including twenty-nine spinal cord ependymomas and sixteen astrocytomas. Though recurrent somatic mutations in IMSCTs were rare, we identifed NF2 mutations in 15.7% of tumors (ependymoma, N = 7; astrocytoma, N = 1), RP1 mutations in 5.9% of tumors (ependymoma, N = 3), and ESX1 mutations in 5.9% of tumors (ependymoma, N = 3). We further identifed copy number amplifcations in CTU1 in 25% of myxopapillary ependymomas. Given the paucity of somatic driver mutations, we further performed whole-genome sequencing of 12 tumors (ependymoma, N = 9; astrocytoma, N = 3). Overall, we observed that IMSCTs with intracranial histologic counterparts (e.g. glioblastoma) did not harbor the canonical mutations associated with their intracranial counterparts. Our fndings suggest that the origin of IMSCTs may be distinct from tumors arising within other compartments of the central nervous system and provides the framework to begin more biologically based therapeutic strategies. Intramedullary spinal cord tumors (IMSCTs) are a heterogeneous group of rare lesions that can cause signifcant morbidity in both children and adults. -

REPORTABILITY Determining Reportability the Following

SECTION II - REPORTABILITY Determining Reportability The following supercedes any previous MCR reportability rules appearing in our manuals. These rules attempt to cover ALL years of case reportability to the MCR, but most specifically refer to diagnoses made beginning in 2003. If there are changes needed in these rules in the future, notification will be sent to reporting facilities and software vendors and replacement pages will be issued for this manual. The MCR requires reporting facilities to submit all cases seen at that facility with neoplasms classified as invasive or in situ in the "Morphology of Neoplasms" section of ICD-O-3* (for cases diagnosed in 2001 and thereafter), ICD-O-2 (for diagnoses made between 1992 and 2000), or ICD-O[-1] (for 1982-1991 diagnoses). (This MCR Manual applies to diagnoses made beginning in 2003, so only ICD-O-3 codes appear here.) If you've changed a listed behavior in an ICD-O book to /2 or /3, that case is also reportable (the "matrix" rule, ICD-O-3 Rule F). The only exceptions to these /2 and /3 reportability rules are the site/morphology combinations that follow: morphology 8000-8005 malignant neoplasms, NOS, of the skin (C44.0-C44.9) 8010-8046 epithelial carcinomas of the skin (C44.0-C44.9) 8050-8084 papillary and squamous cell carcinomas of the skin (C44.0-C44.9) 8090-8110 basal cell carcinomas of the skin (C44.0-C44.9) Note: The above morphologies of any non-C44 primary site will be reportable to the MCR as of January 1, 2004. -

Coexistent Subependymoma and Psammomatous Meningioma

International Medicine 2019; 1(3): 176-177 International Medicine https://www.theinternationalmedicine.com/ Clinical Image Coexistent subependymoma and psammomatous meningioma Richard A. Prayson Department of Anatomic Pathology, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, Ohio, USA Received: 12 April 2019 / Accepted: 10 May 2019 A 74-year-old female with a past medical history of hypertension, congestive heart failure, atrial fibrillation, and type II diabetes mellitus presented most recently with somnolence and nonresponsiveness. She had a known history of a multilobular intraventricular mass within the frontal horn and anterior body of the right lateral ventricle that was discovered on a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) study done six and a half years earlier for complaints at that time of intermittent head pain. The intraventricular lesion was thought to represent a possible central neurocytoma. Also noted at that time were multiple extra-axial masses, presumed to be meningiomas, located at the planum sphenoidale, left clinoid, bilateral falx, and right lateral convexity. Given the patient’s age, medical risk factors, and lack of neurological symptoms and findings directly attributable to the brain masses, it was decided that surgical intervention was not warranted and close follow-up with imaging studies would be done. At the time of her most recent presentation, computed tomography (CT) showed an intraparenchymal hemorrhage in the midline region of the corpus callosum with moderate hydrocephalus and extension of the bleed into the ventricle, proximal to the intraventricular tumor. Surgery was undertaken to remove the blood clot, the intraventricular neoplasm, and a 0.5 cm calcified mass overlying the right frontal gyrus. Figure 1. Psammomatous meningioma arising over the right frontal gyrus (left) and subependymoma situated within the lateral ventricle (right) (hematoxylin and eosin, original magnifications for both images 200X). -

Molecular Clarification of Brainstem Astroblastoma with EWSR1‐ BEND2 Fusion in a 38‐Year‐Old Man

Free Neuropathology 2:16 (2021) Smith‐Cohn et al doi: https://doi.org/10.17879/freeneuropathology‐2021‐3334 page 1 of 8 Case Report Molecular clarification of brainstem astroblastoma with EWSR1‐ BEND2 fusion in a 38‐year‐old man Matthew A. Smith‐Cohn,1,2 Zied Abdullaev,3 Kenneth D. Aldape,3 Martha Quezado,3 Marc K. Rosenblum,4 Chad M. Vanderbilt,4 Fausto J. Rodriguez,5 John Laterra,**2 Charles G. Eberhart**5 1 Neuro‐Oncology Branch, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA 2 Department of Neurology, The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, USA 3 Laboratory of Pathology, Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD, USA 4 Department of Pathology, Memorial Sloan‐Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY, USA 5 Department of Pathology, The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, USA ** These authors contributed equally to this manuscript Corresponding author: Charles Eberhart, MD, Ph.D. ∙ Department of Pathology ∙ The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine ∙ 1800 Orleans St. ∙ Sheikh Zayed Tower ∙ Baltimore, MD 21287 ∙ USA [email protected] Submitted: 21 April 2021 ∙ Accepted: 17 June 2021 ∙ Copyedited by: Calixto‐Hope Lucas ∙ Published: 21. June 2021 Abstract The majority of astroblastoma occur in a cerebral location in children and young adults. Here we describe the unusual case of a 38‐year‐old man found to have a rapidly growing cystic enhancing circumscribed brainstem tumor with high grade histopathology classified as astroblastoma, MN1‐altered by methylome profiling. He was treated with chemoradiation and temozolomide followed by adjuvant temozolomide without progression to date over one year from treatment initiation. -

A Review of Radiographic Imaging Findings of Ependymal Tumors Maria Habib Hanna, MD1*, Bansal A, MD2 and Belani P, MD2

ISSN: 2643-4474 Hanna et al. Neurosurg Cases Rev 2019, 2:028 DOI: 10.23937/2643-4474/1710028 Volume 2 | Issue 2 Neurosurgery - Cases and Reviews Open Access REVIEW ARTICLE A Review of Radiographic Imaging Findings of Ependymal Tumors Maria Habib Hanna, MD1*, Bansal A, MD2 and Belani P, MD2 1Department of Radiology, Weill Cornell Medicine, New York, USA 2 Check for Department of Radiology, Virginia Tech Carilion School of Medicine, Carilion Roanoke Memorial updates Hospital, 1906 Belleview Ave SE, Roanoke, VA 24014, USA *Corresponding author: Maria Habib Hanna, MD, Assistant Professor, Department of Radiology, Weill Cornell Medicine, 525 E 68th St, NY 10065, New York, USA based on imaging. There are, however, imaging features Abstract that can typically be distinguished between the adult Ependymomas are glial tumors that typically arise from the and pediatric patients. For instance, ependymomas in lining of the ventricles or the central canal of the spinal cord. The most common site of occurrence is within the poste- the adult population are typically larger than 4 cm in rior fossa. Subtypes of ependymomas include anaplastic size when they present and often contain cystic com- ependymoma, myxopapillary ependymoma, and subepend- ponents, whereas ependymomas in the pediatric pop- ymoma. Its characteristic imaging features include findings ulation are usually solid and usually smaller in size at of a heterogeneous mass with necrosis, calcifications, cyst- presentation [4]. ic changes, and hemorrhage. Treatment options includes partial resection with or without irradiation. Radiographic features of intracranial ependymomas are summarized in Table 1. Introduction The types of ependymomas to be discussed in this Ependymomas are rare glial tumors that account article include intracranial ependymomas (infra and su- for approximately 7% of all intracranial neoplasms in pratentorial) and spinal (myxopapillary ependymoma). -

910425-Subependymoma-范揚智4.Pdf

Sex: male Date of Birth: 32/11/20 Age: 59 y/o Initial symptom: Persistent headache for about 10+ years, focus on left parietal area. He took medicine bought form drug store in the past.But the headache was getting worse in recent few months, so he come to our OPD Personal and past history: smoking(+), drinking(+) Head injury S/P op 13 years ago, rectal benign tumor S/P op 4 years ago, Cataract S/P op 10 years ago Physical examination and neurological examination has no specific finding LAB: (90/10/27)CBC/DC, PT, APTT, Biochemistry all within normal range Image: MRI Report Precontrast (T1WI, T2WI, FLAIR) and post- contrast (T1WI) brain MR are performed. IMP: An intra-ventricular ependymoma or papilloma occupying the frontal horns of bil. lat. ventricles is more favored. But other possibility (such as: low-grade astrocytoma or central neurocytoma or oligodendroglioma or choroid plexus carcinoma) can not be R/O. The mass is near the rt foramen of Monro, but no direct compreesion to foramen of Monro. Thus, no evidence of hydrocephalus. Lateral Ventricle • F. Monro Subependymal Giant Cell Astrocytoma Subependymoma • Body Subependymoma, etc. • Trigone Child - CPP (Choroid Plexus Papilloma) Adult - Meningioma INTRAVENTRICULAR NEOPLASMS: Ependymoma (and subependymoma) Choroid plexus papilloma Subependymal giant cell astrocytoma Meningioma Colloid cyst (3rd) Central neurocytoma Medulloblastoma (4th) Mets, lymphoma, Germ Cell Ependymoma In adult: arise in the trigone of the lateral ventricle or near the foramen of Monro. Can be periventricular or intraventricular In children (1st to 2nd decade): common in post. fossa, arising in the 4th ventricle. -

Molecular Cytogenetic Analysis in the Study of Brain Tumors: Findings and Applications

Neurosurg Focus 19 (5):E1, 2005 Molecular cytogenetic analysis in the study of brain tumors: findings and applications JANE BAYANI, M.H.SC., AJAY PANDITA, D.V.M., PH.D., AND JEREMY A. SQUIRE, PH.D. Department of Applied Molecular Oncology, Ontario Cancer Institute, Princess Margaret Hospital, University Health Network; Arthur and Sonia Labatt Brain Tumor Research Centre, Hospital for Sick Children; and Departments of Laboratory Medicine and Pathobiology and Medical Biophysics, University of Toronto, Ontario, Canada Classic cytogenetics has evolved from black and white to technicolor images of chromosomes as a result of advances in fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) techniques, and is now called molecular cytogenetics. Improvements in the quality and diversity of probes suitable for FISH, coupled with advances in computerized image analysis, now permit the genome or tissue of interest to be analyzed in detail on a glass slide. It is evident that the growing list of options for cytogenetic analysis has improved the understanding of chromosomal changes in disease initiation, progression, and response to treatment. The contributions of classic and molecular cytogenetics to the study of brain tumors have pro- vided scientists and clinicians alike with new avenues for investigation. In this review the authors summarize the con- tributions of molecular cytogenetics to the study of brain tumors, encompassing the findings of classic cytogenetics, interphase- and metaphase-based FISH studies, spectral karyotyping, and metaphase- and array-based comparative genomic hybridization. In addition, this review also details the role of molecular cytogenetic techniques in other aspects of understanding the pathogenesis of brain tumors, including xenograft, cancer stem cell, and telomere length studies.