Education in the Te Aroha District in the Nineteenth Century

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Saving the Old Kopu Bridge

Saving the Old Kopu Bridge Business Management Plan 2016 Thames Heritage Festival Open Day 13 March 2016. Sereena Burton photo A Bridge to the Future Promoting heritage protection, tourism and prosperity Local icon Cycleway link Tourism feature Transport history Engineering history International significance Presented by the Historic Kopu Bridge Society May 2016 Table of Contents 1 Executive Summary ............................................................................................................ 4 2 Letters of Support ............................................................................................................... 5 3 Introduction ...................................................................................................................... 17 3.1 Purpose...................................................................................................................... 17 3.2 Why the Kopu Bridge matters to all of us ................................................................. 17 3.3 Never judge a book by its cover!............................................................................... 18 4 Old Kopu Bridge ................................................................................................................ 19 4.1 Historical Overview ................................................................................................... 19 4.2 Design ........................................................................................................................ 21 5 Future of the -

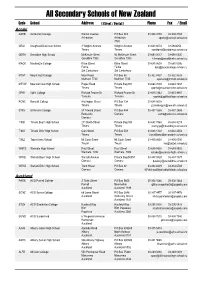

Secondary Schools of New Zealand

All Secondary Schools of New Zealand Code School Address ( Street / Postal ) Phone Fax / Email Aoraki ASHB Ashburton College Walnut Avenue PO Box 204 03-308 4193 03-308 2104 Ashburton Ashburton [email protected] 7740 CRAI Craighead Diocesan School 3 Wrights Avenue Wrights Avenue 03-688 6074 03 6842250 Timaru Timaru [email protected] GERA Geraldine High School McKenzie Street 93 McKenzie Street 03-693 0017 03-693 0020 Geraldine 7930 Geraldine 7930 [email protected] MACK Mackenzie College Kirke Street Kirke Street 03-685 8603 03 685 8296 Fairlie Fairlie [email protected] Sth Canterbury Sth Canterbury MTHT Mount Hutt College Main Road PO Box 58 03-302 8437 03-302 8328 Methven 7730 Methven 7745 [email protected] MTVW Mountainview High School Pages Road Private Bag 907 03-684 7039 03-684 7037 Timaru Timaru [email protected] OPHI Opihi College Richard Pearse Dr Richard Pearse Dr 03-615 7442 03-615 9987 Temuka Temuka [email protected] RONC Roncalli College Wellington Street PO Box 138 03-688 6003 Timaru Timaru [email protected] STKV St Kevin's College 57 Taward Street PO Box 444 03-437 1665 03-437 2469 Redcastle Oamaru [email protected] Oamaru TIMB Timaru Boys' High School 211 North Street Private Bag 903 03-687 7560 03-688 8219 Timaru Timaru [email protected] TIMG Timaru Girls' High School Cain Street PO Box 558 03-688 1122 03-688 4254 Timaru Timaru [email protected] TWIZ Twizel Area School Mt Cook Street Mt Cook Street -

Audit & Risk Committee Agenda

- Will do now. A G E N D A Date: Wednesday 31 August 2016 Time: 9.00am Venue: Council Chambers William Street Paeroa L D Cavers Chief Executive Members: J P Tregidga (His Worship the Mayor) Cr B A Gordon (Deputy Mayor) Cr D A Adams Cr J M Bubb Cr G A Harris Cr P H Keall Cr G R Leonard Cr M P McLean Cr P A Milner Cr H T Shepherd Cr D H Swales Cr J H Thorp Cr A A Tubman Distribution: Elected Members: Staff: Public copies: Press copies: His Worship the Mayor L Cavers Paeroa Office Waihi Leader Cr D A Adams A de Laborde Plains Area Office Cr J M Bubb P Thom Waihi Area Office Cr B A Gordon S Fabish Cr G A Harris D Peddie Cr P H Keall M Buttimore Cr G R Leonard Council Secretary Cr M P McLean Cr P A Milner Cr H T Shepherd Cr D H Swales Cr J H Thorp Cr A A Tubman HAURAKI DISTRICT COUNCIL MEETING NOTICE IS HEREBY GIVEN THAT A MEETING OF THE HAURAKI DISTRICT COUNCIL WILL BE HELD IN THE COUNCIL CHAMBERS, WILLIAM STREET, PAEROA ON WEDNESDAY 31 AUGUST 2016 COMMENCING AT 9.00 AM Morning tea will be available at 10.15 am. PRESENTATION 11.30am Presenter: Paeroa College Principal, Mr Doug Black Subject: Hauraki Secondary Tertiary Concept Project ORDER OF BUSINESS 1. APOLOGIES Pages 2. DECLARATION OF LATE ITEMS Pursuant to Section 46A(7) of the Local Government Official Information and Meetings Act 1987, the Chairman is to call for late items to be accepted. -

COMMUNITY PLAN a Vision for Coromandel’S Communities 2006 - 2016

COMMUNITY PLAN A Vision for Coromandel’s Communities 2006 - 2016 1 2 Contents The Steering Committee would like to say . 3 How will this Community Vision Plan work? . 4 Our Guiding Principles. 5 Partnership . 6 What our community currently looks like . 7 Ward Map . 9 Coromandel/Colville Ward in 2016 . 10 Key Issues . 14 Arts . 15 Beautifi cation . 16 Buildings (residential/commercial/industrial) . 18 Business (retail/commercial) . 19 Home-based Ventures . 20 Community Assets . 21 Community Well-being . 23 Development and Growth . 25 Education. 27 Employment. 29 Funding Opportunities . 30 Harbour and Sea . 31 Heritage & Culture . 33 Industry, Farming and Forestry . 35 Infrastructure - Communication . 37 1 Infrastructure - Power . 38 Infrastructure - Sewerage . 39 Infrastructure - Solid Waste . 40 Infrastructure - Roading and Transport . 41 Infrastructure – Water and storm water . 43 Natural Environment . 45 Parks, Reserves & Open Spaces . 48 Promotion/Tourism. 49 Public Safety . 51 Sport and Recreation. 53 Rural Communities . 54 Colville . 55 Port Jackson . 63 Port Charles. 68 Coromandel Area School Students . 72 2 The steering committee would like to say … It is a statutory requirement (Local Government Act 2002) that all Communities complete a Community Outcomes Plan and for it to be in place by 2004. In 2001 the community was invited to attend a series of community planning workshops that were held to focus on the future direction of sport and the development of the ward. This steering committee was established with volunteers who attended those workshops. This steering committee feels very strongly about developing a community plan that refl ects the beliefs and aspirations that residents and ratepayers have for the future of this ward - the area they live, work and play in, to 2014. -

Thames Coromandel District Sport and Active Recreation Plan

Thames Coromandel District Sport and Active Recreation Plan 2019-2029 Thames Coromandel District Council Private Bag 1001, Thames, 3540 515 Mackay Street, Thames Ph: 07 868 0200 Email: [email protected] Executive summary Sport, recreation, play and physical activity has a crucial role to play in building connected, healthy and vibrant communities. New Zealanders’, individually and collectively, value the role physical activity plays in their lives. More specifically in the Thames Coromandel District 83% of adults (18 years and older) feel that being physically active in the great outdoors is an important part of New Zealanders’ lives. Thames Coromandel District has a strong Sport and Active recreation sector, where opportunities are provided for the resident population of the district and also a large influx of summer visitors into the area. Thames Coromandel has a unique combination of future challenges including rising water levels, significant and increasing proportion of the resident population of retirement age and large fluctuations in seasonal populations. All of these factors contribute towards the need for considered planning to ensure future provision of sport and active recreation opportunities meets the future needs of the community. Thames Coromandel District Council and Sport Waikato work together to support the provision of sport, recreation, play and physical activity opportunities for the Thames Coromandel community. Working together, both organisations recognise a need to deliver a coordinated, collaborative and clear plan to lead, enable and guide future provision of sport, recreation and physical activity opportunities for the people of the Thames Coromandel District. The Thames Coromandel District Sport and Active Recreation Plan (The Plan) is designed to provide direction for future investment and focus for both the Thames Coromandel District Council, Sport Waikato and providers of sport in the district. -

TVRU 2021 HANDBOOK Final 1

HANDBOOK 2021 Your Host Terry & Rhonda Williams 2a Arney Street Paeroa New Zealand T: 07 862 8788 F: 07 862 8789 E: [email protected] Reservations Freephone 0800 579 645 www.pedlarsmotel.nz 502 Pollen Street, Thames 37 Orchard West Road, Ngatea 601 Port Road, Whangamata 25 Seddon Street, Waihi ! SPONSOR OF THAMES VALLEY RUGBY Contents Message from the Union ................................................................................... 2 Executive Officers / Life Members / Board of Management ................................ 3 Union Staff / Youth Management Board ............................................................. 4 Board of Management Sub Committees ............................................................ 5 Heartland Management Team ........................................................................... 6 Honorary Professionals / Disciplinary Committee ............................................... 8 Appeals Committee / Referee’s Advisory Committee .......................................... 9 Secondary Schools ......................................................................................... 10 Te Aroha Sub-Union ........................................................................................ 11 Club Directory ........................................................................................... 12-25 Disciplinary Procedures ............................................................................... 26-27 HG Leach Senior A Draw ........................................................................... -

'Overwhelming' Road Costs Cancel Charity Market

Celebrity chef Simon Gault names Miranda blue cod meal ‘best in North Is’, P4 Ngatea to go up in smoke, P7 ISSN 2703-5700 NOW PUBLISHED EVERY SECOND WEDNESDAY Issue 011 January 20, 2021 ‘Overwhelming’ Fun and games at show The 121st Paeroa & Plains Show C 100 C 0 went off without a hitch at roadM 25 M 0 costs cancel Y 0 Y 0 Kerepēhi Domain on January K 0 K 100 9, with equestrian events, lawn mower racing and charity market great food and Thames-Coromandel Mayor entertainment. ByFont KELLEY :: TANTAUTimes (modified) Sandra Goudie said road closure More photos: xorbitant compliance costs costs were not dictated by council, page 19. Ehave brought to a halt a and were something organisers long-running community event had “to take into account”. that raised money for youth pro- “The decisions they make are grammes in the area. entirely over to them. We do what The Thames Rotary Gold Rush we can to help, but we’re not going Market was set to be held on Jan- to carry the burden of these things uary 9 but according to organis- cost-wise, because it would fall on ers, costs “overwhelmed” them the ratepayers,” she said. and they were forced to cancel. “It is a shame, because these Shutting the main street for one things are always good. If they day would have set the service or- plan ahead, they might be able to ganisation back $7000. fi nd a way to meet those costs, but It’s a cost the district mayor if they don’t, that’s a choice they says is a common problem for have to make.” event organisers - but one they Council roading manager Ed should take into account. -

Track and Field Results

NZSS Track and Field & Road Championships Tauranga Domain - 11/12/2020 to 13/12/2020 Results Event 35 Boys Javelin Throw 700g Junior 1 Stiaan Botes Mt Maunganui College 62.57m 2 Bradley Bidois Cambridge High School 51.67m 3 Andre Gundersen Paraparaumu College 46.17m 4 Finn Burridge Kristin School 46.14m 5 Daniel Shaw YC Westlake Boys High School 42.89m 6 Tyler Farquhar Papamoa College 38.25m 7 Harrison McGregor Aquinas College 36.83m 8 Sonny Reynolds Thames High School 36.71m 9 Tai Rhodes Westlake Boys High School 35.92m 10 MacLean Forbes St Patrick’s College Silverstream 35.80m 11 Antonie Smal Sancta Maria College 35.10m 12 Chace Large Rototuna High School 34.77m 13 Dian Jacobs Hamilton Boys High School 32.65m 14 Blaine Knapman St Patrick’s College Silverstream 31.51m 15 William Kirk Green Bay High School 31.22m 16 Aphichat Khothisen Green Bay High School 27.17m 17 Nikora Bright Edgecumbe College 24.73m -- Dustin Miller St Patrick’s College Silverstream NM Event 36 Girls Javelin Throw 500g Junior 1 Ruby Donnelly Motueka High School 33.60m 2 Kirsty McCarthy-Dempsey Darfield High School 33.07m 3 Leala Willman Napier Girls High School 32.79m 4 Khushi Kansara Motueka High School 32.03m 5 Mia Bartlett Wairarapa College 29.77m 6 Ariana Mudgway Motueka High School 29.74m 7 Isla Feek Wellington Diocesan School for Girls 26.02m 8 Bridget Trott Whanganui Collegiate 25.08m 9 Jessica Lake Waitaki Girls High School 24.41m 10 Awatea Carswell Wairarapa College 24.18m 11 Chelsey Moananu Wellington East Girls College 24.01m 12 Ashleigh Devine Rototuna -

TCDC Community Study Report Thames 11-6-10

TCDC Heritage Review Project Coromandel Peninsula Community Board Heritage Study - Thames - Dr Ann McEwan Heritage Consultancy Services Hamilton 11 June 2010 Executive Summary This study is intended to assist the Thames-Coromandel District Council in its forthcoming review of the District Plan. Historic heritage recommendations specific to the Thames Community Board area are provided here for consideration by the Council and discussion by local iwi and other members of the community. This report should be read in conjunction with the Coromandel Peninsula Thematic History and Consultant’s Summary Recommendation Report (2010), also prepared by Heritage Consultancy Services. In them a thematic approach has been taken to compiling historical information in a format that is best suited to identifying and interpreting historic heritage resources in the district. The principal recommendation made within this report is that the historic heritage resources of Thames and surrounding areas should be protected, actively managed and interpreted by the council on behalf of the community. Whilst scheduling of some historic buildings, sites and places on the District Plan is desirable, heritage values can also be conserved on council reserves and the DoC estate. The history of the locality may also be recorded and disseminated by the Thames Library, in partnership with The Treasury and The Coromandel Heritage Trust. Historic heritage resources in the area can be enhanced or undermined by new development, whether undertaken by the council or private landowners. It is therefore desirable that the history of the area is promoted within council and throughout the wider community in order that the future of local area settlements and their environs is based on an understanding of the past. -

Thames Kauaeranga Kāhui Ako AC

Te Kāhui Ako o Te Kauaeranga Thames Community of Learning Achievement Challenges 2020-2023 Introduction Our Whakatauki E hora waikohu āroto, E maupaki ā waho, Our Vision Tēnā mē piki atu, piki ai, ki te pikinga ora mōu Climb, Ascend, Persevere While a mistiness lurks within, without are clear skies, Therefore strive Tēnā mē piki atu, piki ai, ki te pikinga ora mōu and climb to discover your true potential and thus attain the zenith of your well being. Our Purpose This Taimoana Turoa Whakataukī was gifted to the Thames Kauaeranga Kāhui Ako by Ngāti Maru Iwi in 2017 to affirm the vision for our journey Our Kāhui Ako will reflect our unique and diverse community* ahead. ECE and give our students consistent, high quality education at all levels. Our Values Through Conscious Collaboration, Connection and Inclusion Whakawhanaungatanga we will strive to achieve equity and excellence for all ākonga/ learners. We will enhance the connections to strengthen relationships Primary between and within our Kāhui Ako community. Our Kāhui Ako will give effect to Te Tiriti o Waitangi by Manaakitanga working to ensure that our strategic direction, vision and values reflect local tikanga Māori, mātauranga Māori and te We will be respectful, encouraging and supportive of all in our ao Māori, and by supporting the teaching and learning of te Kāhui Ako community. reo Māori and tikanga Māori. Secondary Kotahitanga Our students will experience a seamless transition from Early Childhood Education through Primary, Secondary School and We are committed to achieving our shared vision through beyond. working together with a unity of purpose. -

Education Region (Total Allocation) Cluster

Additional Contribution to Base LSC FTTE Whole Remaining FTTE Total LSC for Education Region Resource (Travel Cluster Name School Name School Roll cluster FTTE based generated by FTTE by to be allocated the Cluster (Total Allocation) Time/Rural etc) on school roll cluster (A) school across cluster (A + B) (B) Colville School 37 0.07 Coroglen School 31 0.06 Coromandel Area School 197 0.39 Hikuai School 54 0.11 Coromandel Community of Learning Opoutere School 96 0.19 2 1 1 3 Tairua School 138 0.28 Te Rerenga School 71 0.14 Whangamata Area School 492 0.98 1 Whenuakite School 123 0.25 Hauraki Plains College 782 1.56 1 Kaiaua School 17 0.03 Kaihere School 37 0.07 Kerepehi School 65 0.13 Kopuarahi School 17 0.03 Mangatangi School 104 0.21 Hauraki Community of Learning 4 3 0 4 Mangatawhiri School 187 0.37 Maramarua School 57 0.11 Ngatea School 336 0.67 Orere School 28 0.06 Turua Primary School 95 0.19 Waitakaruru School 73 0.15 Aberdeen School 637 1.27 1 Crawshaw School 308 0.62 Forest Lake School 348 0.70 Frankton School 656 1.31 1 Fraser High School 1,460 2.92 2 Waikato Horotiu School 239 0.48 He Waka Eke Noa (NW Hamilton) Community of Learning Maeroa Intermediate 781 1.56 12 1 6 0 12 Nawton School 485 0.97 1 Rhode Street School 210 0.42 Te Kowhai School 280 0.56 Vardon School 310 0.62 Whatawhata School 273 0.55 Whitiora School 235 0.47 Huntly College 212 0.42 Huntly School (Waikato) 207 0.41 Huntly District Community of Learning 1 1 0 1 Ruawaro Combined School 58 0.12 Taupiri School 73 0.15 Kio Kio School 111 0.22 Maihiihi School 96 0.19 -

Thames Ward Sport and Recreation Facilities Review and Future Directions

THAMES WARD SPORT AND RECREATION FACILITIES REVIEW AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS Prepared for Thames Coromandel District Council December 2013 © SGL Funding Ltd 2013 – Thames Ward Sport and Recreation Facilities Review and Future Directions 1 CONTENTS: 1 Review of Thames Ward Community Sport and Recreation .................................................... 6 1.1 Study Objectives and Key Areas of Work .................................................................................. 6 1.2 Methodology ................................................................................................................................... 7 1.2.1 Base Information .................................................................................................................... 7 2 About Thames Town ...................................................................................................................... 8 2.1 Introduction and Location ............................................................................................................ 8 2.1.1 Council Direction ................................................................................................................... 8 2.1.2 Population ............................................................................................................................... 9 2.2 Key Strategic Directions and Community Initiatives .............................................................. 12 2.2.1 Thames Urban Development Strategy ...........................................................................