Thesis Was Printed with Financial Support from the Amsterdam School for Cultural Analysis (ASCA), University of Amsterdam

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Your Name Here

PHENOMENAL BODIES, PHENOMENAL GIRLS: HOW YOUNG ADOLESCENT GIRLS EXPERIENCE BEING ENOUGH IN THEIR BODIES by HILARY ELIZABETH HUGHES (Under the Direction of Mark D. Vagle) ABSTRACT Drawing on philosophers (Ahmed, 2006; Fanon, 1986; Heidegger, 1927, 1962, 1992; Merleau-Ponty, 1962) and social science scholars (Dahlberg, Dahlberg, & Nystrom, 2008; Vagle, 2009, 2010, 2011; van Manen, 1990, 2000) for this phenomenological study, I asked what it was like for the seventh grade girls who participated with me in a year-long writing group to experience moments where they found themselves in bodily-not-enoughness: moments when someone or something was telling them they were not enough of something in their bodies. Using a multigenre magazine format for the dissertation, I describe how I learned—as an adult, a qualitative researcher, a middle grades teacher, and a teacher educator—from these seventh grade girls how to be-enough in my own body, by illustrating various moments when some of the girls seemed to talk-back-TO those societal messages telling them they were not pretty- enough, thin-enough, English-speaking-enough, white-enough, popular-enough, or smart-enough by embodying some kind of resistance-to those messages. I then suggest that if we as adults, qualitative researchers, middle grades educators, and teacher educators wish to try and understand better how female young adolescents of color experience living in their bodies, we should begin listening differently so that we can begin seeing/knowing/thinking the bodies of young adolescents, -

Gogebic Community College Holds 83Rd Commencement by IAN MINIELLY Tional Students Tend to Not Be Full Time [email protected] Or Between the Ages of 18-24

Partly cloudy High: 63 | Low: 40 | Details, page 2 DAILY GLOBE yourdailyglobe.com Saturday, May 13, 2017 75 cents ‘TONIGHT IS DEDICATED TO YOU’ Gogebic Community College holds 83rd commencement By IAN MINIELLY tional students tend to not be full time [email protected] or between the ages of 18-24. The stu- IRONWOOD — Gogebic Community dent has frequently already held a job College president Jim Lorenson, in his for an extended period of time, poten- welcoming remarks before introducing tially already raised a family or at least John Lupino, chairperson, for the 83rd is well on the way to raising a family. Or commencement in GCC history, said to is an adult just looking for a different the assembled students filling the career path and using an education to lindquist Center, “Tonight is dedicated achieve it. to you.” Seeing the wide variety of graduates The production required to get the Friday night before and during com- right people on stage, the faculty in two mencement, brought back the effort the lines for the graduates to navigate while school’s board and Ryon List, Dean of shuffling students through this same Instruction, are putting forth to make tunnel consisting of faculty, put the GCC available and worthwhile to people emphasis on the graduates and kept the seeking an education that transfers to a procession moving forward. follow on college or into an immediate One cannot say kids graduating when career. discussing college graduation, as many Marcia Long, the guest speaker, non-traditional students return to col- pointed out the rarified air the gradu- leges across the county every year for ates would be breathing at the conclu- additional job training, career advance- sion of the evening, when she pointed ment, or just plain old learning for the out less than 7 percent of the world has sake of learning. -

Fassio Egg Farms Starts to Cleanup After Fire

FRONT PAGE A1FRONT PAGE A1 J&J Jewelry still going strong after 27 years See A10 TOOELETRANSCRIPT SERVING TOOELE COUNTY BULLETIN SINCE 1894 THURSDAY September 7, 2017 www.TooeleOnline.com Vol. 124 No. 29 $1.00 Fassio Egg Farms starts to cleanup after fire STEVE HOWE ly 600,000 remaining chickens STAFF WRITER are unable to get to refrigera- A day after a fire destroyed tion quickly enough without two chicken coops and killed the conveyer system, Larsen as many as 300,000 chickens said. As a result, all of the eggs at Fassio Egg Farms in Erda, produced since the fire must employees were beginning to be disposed of, he said. clear debris. The conveyer system is “We’re cleaning up as best a priority for the farm and as we can,” said Corby Larsen, Larsen said they hope to have vice president of operations at some version of the system in Fassio Egg Farms. place within the next couple of FRANCIE AUFDEMORTE/TTB PHOTOS The two chicken coops days. The farm is also looking destroyed in the fire were con- to replace the chickens killed Ashlyn, KedRick and Melinda Hunsaker (left) listen while Adriana Padillo with The Brothers Restaurant explains about the eatery’s offerings at the Taste of Our County, Business and Career Showcase at the Benson Grist Mill on Wednesday. nected to the additional coops in the fire within the next few and processing plant by a weeks. conveyer system, which trans- Chickens in the adjacent ported the eggs, Larsen said. coops are being monitored Chamber draws big crowd to grist mill The fire used the conveyer sys- for effects from the fire and tem connection to spread from smoke, Larsen said. -

2009-02-20.Pdf2013-02-12 15:4711.9 MB

ISIE: EA & WEESS ATLANTIL\I TV SIGS IAY, EUAY 20, 200 l. . 06 I 24 rntdEWS I Et Kntn I Extr I Grnlnd I ptn I ptn h I ptn! ll Knntn I fld I rth ptn I I h I Sbr I Sth ptn I Strth Cnnll Cntn C I .Atlnt.M I 0 El Strt, Slbr, MA 02 . (60 26 I EE • AKE OE ! \ rr`r v t 4, 4 ,, k 4 .‘ 44.:"‘d !1'.'4Ajr2rvIr—4.".44..444%t:: ?r A 7 6...lp t6. • ...zn s Snn n r‘ltl l Crimestoppers: Putting the puzzle together Y MA CAG f. fnd rdrd n hr Ch t fr t n Ilntn Strt AAAMC EWS SA WIE pl Strt prtnt, lld b h lln 26rld r thr llr ln v tr t th hd. ph ln nd 2r 'Sometimes we're n td, h rn nlvd. ld rr Gl. Al ht Ah hv nvr bn h flln r, 20 n th blz nd l just missing that brht t jt fr thr rld ttl r, h nd t p r? l fnd rdrd, bt ltr bd t vr one last piece to It vr pbl. t rlt f v hd nj brn tnd n th nfr the puzzle.' ld b th n t hlp lv r, n hr Mpld Av n. Whvr trtd th fr th tr. n prtnt. h nvr bn ht. t h Grll On Mnd, Sptbr ht , t, rn tl, t 8 r rtth PD 28, nrl 0 r , 2 nlvd. th vr , hn rld r Krnptn ntthr r , n Mr nd Stll ltn r Otbr , 86, n rnt bth fnd rdrd n thr UE Ct n A• AGE 2A I AnAlsrnc EWS EUAY 20, 2009 I Vot_ 35, No 06 AtthrlCEWS.COM WEAE E WEEKE rd, brr 20 Strd, brr 2 Snd, brr 22 Mnd, brr 2 brr 24 h: ° :° h: 28° : 4° h:0° : ° h: 28° : 6° Mn 1 , . -

Star Channels, June

JUNE 3 - 9, 2018 staradvertiser.com FAMILY FEUD Logan Roy (Brian Cox) controls one of the world’s biggest media and entertainment conglomerates in the new drama Succession. As the aging patriarch approaches his twilight years, his four children consider what the future holds for them. Jeremy Strong, Kieran Culkin, Sarah Snook and Alan Ruck play the Roy siblings. Premiering Sunday, June 3, on HBO. NEW EPISODES! Join host, Lyla Berg, as she invites you to visit some Meet the people of Hawai‘i’s most cherished landmarks and sits down with guests who share their work on moving and places our community forward. Tune in to new episodes that make of Island Focus the first and third Wednesday 1st & 3rd of each month, 6:30pm on Channel 53. Hawai‘i special. Wednesday of the Month Also available on Video On-demand Channel 52, olelo.org | - - 6:30 pm Channel 53 ‘Olelonet and ‘Olelo YouTube. ON THE COVER | SuccessION Father knows best An aging patriarch fights see how massive wealth and power distorts features Hiam Abbass (“Lemon Tree,” 2008) as and twists and wounds this family.” Logan’s third wife, Marcy, a formidable force in for his company in HBO’s Set in New York City, HBO’s newest drama her own right. ‘Succession’ takes a look at politics, money and power The remaining staff includes COO Frank as the characters consider what the future (Peter Friedman, “Safe,” 1995), who acts as a By Kyla Brewer might hold for them when Logan steps down mentor for Kendall. Allesandro (Parker Sawyers, TV Media from Waystar. -

Cassie Helps Her Students Gain a Fresh Perspective

THE MAGIC IS BACK ON SUNDAYS! CASSIE HELPS HER STUDENTS GAIN A FRESH PERSPECTIVE WHILE JOY’S DREAM MAY SHINE A NEW LIGHT ON THE MERRIWICK-DAVENPORT CURSE ON ‘GOOD WITCH’ PREMIERING JUNE 7, ON HALLMARK CHANNEL STUDIO CITY, CA – May 13, 2020 – Cassie’s (Catherine Bell, “Army Wives,” “JAG”) art history lesson has an impact on one student beyond the classroom on “Good Witch,” while Joy (Katherine Barrell, “Wynonna Earp”) has a troubling dream that may not be what it seems in “The Dream,” premiering Sunday, June 7 (9 p.m. ET/PT), on Hallmark Channel. Cassie moves her art history class to the local museum where her lesson on perspective transcends the art world and has an impact on her students beyond the classroom. Sam (James Denton, “Devious Maids, “Desperate Housewives”) performs surgery on Adam (Scott Cavalheiro, “Mary Kills People”) and although all goes well, only time will tell if he makes a full recovery. Joy (Katherine Barrell, “Wynonna Earp”) is upset by her dream about Abigail (Sarah Power, “The Killjoys”) and Donovan (Marc Bendavid, “Murdoch Mysteries”) but what first appears to be a dark cloud over their relationship could give way to a silver lining. Mayor Martha (Catherine Disher, “Abby Hatcher”) is excitedly preparing to host a small delegation from a town in France in hopes of Middleton being named its sister city. But when her overtures with a French flair fall flat, she takes George’s (Peter MacNeill, “This Life”) advice and pivots her plans to throw an all-American party complete with an impromptu musical performance by two of Middleton’s own. -

A TIDAL WAVE. Anyone with a Little Passion Can Start a Movement in Their Community

AUGUST 12 - 18, 2018 staradvertiser.com SOCAL DRAMEDY When former surfer Dud (Wyatt Russell) fi nds a ring on the beach, it leads him to a rundown fraternal lodge in Lodge 49. Middle-aged plumbing salesman Ernie Fontaine (Brent Jennings) takes him under his wing and welcomes him to the club. Sonya Cassidy also stars in the freshman comedy-drama as Dud’s twin sister, Liz. Airing Monday, Aug. 13, on AMC. Even the tiniest voice can start A TIDAL WAVE. Anyone with a little passion can start a movement in their community. Champion an issue. Cheer an event. Support a cause. ¶ũe^ehbla^k^mh^fihp^krhnpbma the training, equipment and airtime you need so your olelo.org voice can be heard. Visit olelo.org. ON THE COVER | LODGE 49 Fresh start Slacker surfer finds new belly up. While she mostly keeps it together, Liz Benjamin,” 1980) and Kurt Russell (“Escape can sometimes lose it under the pressure of from New York,” 1981) worked his way up purpose in ‘Lodge 49’ modern life. through the entertainment industry after an Their tragic loss and precarious financial injury halted his burgeoning hockey career. By Kyla Brewer situation makes the Dudley twins relatable for He appeared in such films as “Escape from TV Media many, and “Lodge 49” executive producer Jeff L.A.” (1996), “This Is 40” (2012) and “22 Jump Freilich (“Halt and Catch Fire”) is confident that Street” (2014). He also co-starred in the indie s television continues to evolve, some viewers will connect with the characters. film “Folk Hero & Funny Guy” (2016), and has series seem to defy and transcend “Each of the characters in this show are so appeared in the acclaimed British anthology Agenres, mixing elements of comedy and well defined and so real that I know all of them,” series “Black Mirror.” drama in the same hour — sometimes even Freilich said in a promo for the new series. -

Catégories En Télévision

CATÉGORIES EN TÉLÉVISION Best TV Movie #Roxy Super Channel (Allarco Entertainment) (Mosaic Entertainment) Camille Beaudoin, Eric Rebalkin Believe Me: The Abduction of Lisa McVey Showcase (Corus Entertainment) (Cineflix (Believe Me) Inc.) Jeff Vanderwal, Charles Tremayne, Sherri Rufh, Kim Bondi Claws of the Red Dragon (China's Truth) NTDTV (New Tang Dynasty Television (Canada)) (2600641 Ontario Inc (New Realm Studios)) Kevin Yang, Sophia Sun, Joe Wang, Joel Etienne Daughter of the Wolf Rogers on Demand (Rogers Media) (Minds Eye Entertainment / Falconer Pictures) Kevin DeWalt, Douglas Falconer, Benjamin DeWalt, Danielle Masters Nowhere To Be Found (Rogers/Telus/Shaw) (Nowhere To Be Found Productions Inc.) Paolo Mancini, Thomas Michael Best Drama Series Anne With An E CBC (CBC) (Northwood Anne Trois Inc) Miranda de Pencier, Moira Walley-Beckett Cardinal CTV (Bell Media) (Sienna Films) Jennifer Kawaja, Julia Sereny, Patrick Tarr, Daniel Grou, Jocelyn Hamilton, Armand Leo Coroner CBC (CBC) (Muse Entertainment, Back Alley Films, Cineflix Studios) Adrienne Mitchell, Morwyn Brebner, Jonas Prupas, Peter Emerson, Brett Burlock Mary Kills People Global (Corus Entertainment) (Cameron Pictures) Jocelyn Hamilton, Amy Cameron, Tassie Cameron, Marsha Greene, Tecca Crosby Vikings History (Corus Entertainment) (Take 5 Productions Inc.) Sheila Hockin, John Weber, Michael Hirst, Morgan O'Sullivan, James Flynn, Alan Gasmer, Sherry Marsh, Bill Goddard Best Comedy Series Jann CTV (Bell Media) (Project 10, Seven24 Films) Jann Arden, Leah Gauthier, Jennica Harper, -

TV Shows (VOD)

TV Shows (VOD) 11.22.63 12 Monkeys 13 Reasons Why 2 Broke Girls 24 24 Legacy 3% 30 Rock 8 Simple Rules 9-1-1 90210 A Discovery of Witches A Million Little Things A Place To Call Home A Series of Unfortunate Events... APB Absentia Adventure Time Africa Eye to Eye with the Unk... Aftermath (2016) Agatha Christies Poirot Alex, Inc. Alexa and Katie Alias Alias Grace All American (2018) All or Nothing: Manchester Cit... Altered Carbon American Crime American Crime Story American Dad! American Gods American Horror Story American Housewife American Playboy The Hugh Hefn...American Vandal Americas Got Talent Americas Next Top Model Anachnu BaMapa Ananda Ancient Aliens And Then There Were None Angels in America Anger Management Animal Kingdom (2016) Anne with an E Anthony Bourdain Parts Unknown...Apple Tree Yard Aquarius (2015) Archer (2009) Arrested Development Arrow Ascension Ash vs Evil Dead Atlanta Atypical Avatar The Last Airbender Awkward. Baby Daddy Babylon Berlin Bad Blood (2017) Bad Education Ballers Band of Brothers Banshee Barbarians Rising Barry Bates Motel Battlestar Galactica (2003) Beauty and the Beast (2012) Being Human Berlin Station Better Call Saul Better Things Beyond Big Brother Big Little Lies Big Love Big Mouth Bill Nye Saves the World Billions Bitten Black Lightning Black Mirror Black Sails Blindspot Blood Drive Bloodline Blue Bloods Blue Mountain State Blue Natalie Blue Planet II BoJack Horseman Boardwalk Empire Bobs Burgers Bodyguard (2018) Bones Borgen Bosch BrainDead Breaking Bad Brickleberry Britannia Broad City Broadchurch Broken (2017) Brooklyn Nine-Nine Bull (2016) Bulletproof Burn Notice CSI Crime Scene Investigation CSI Miami CSI NY Cable Girls Californication Call the Midwife Cardinal Carl Webers The Family Busines.. -

Don't Panic Over Nfl Ratings Decline

www.cablespots.net Published Daily For Subscription call 1-888-884-2630 Fax: 866-870-6989 [email protected] $250 Per Year Monday, October 17, 2016 Copyright 2016. DON’T PANIC OVER NFL RATINGS DECLINE ‘STILL THE ULTIMATE REALITY SHOW’ ADVERTISER NEWS Ratings for NFL games have been down by more The Commerce Department says retail sales rose than 10% this new season—which has the league and 0.6 percent in September, a rebound after sales slipped TV networks scrambling to understand what’s going on. 0.2 percent in August. So far this year, retail sales have But sports management and marketing experts at the increased 2.9 percent compared with 2015. Sales rose 2.4 University of Maryland’s Robert H. Smith School of percent at gas stations, spending at restaurants improved Business say there’s no need to panic—that the NFL TV 0.8 percent, and auto dealers, building materials stores ratings lag is essentially a blip triggered by various factors, and furnishers notched monthly gains of 1 percent or from relative outliers like Clinton-Trump presidential more….Chinese automaker Geely has announced a new election drama and National Anthem demonstrations to auto brand. The company is launching Lynk & Company enduring trends like fantasy sports. to build “mid-market” cars, which will be Former AOL and NFL executive available first in China, then in the U.S. Derrick Heggans, now a professor in and Europe. It’s the first vehicle based UMD’s Department of Logistics, Business on the Complex Modular Architecture and Public Policy, says those eyeballs are (CMA) platform developed by Geely and coming back. -

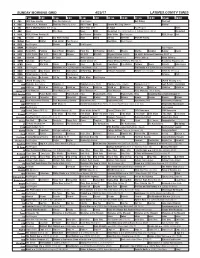

Sunday Morning Grid 4/23/17 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 4/23/17 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program Bull Riding PGA Golf 4 NBC Today in L.A.: Weekend Meet the Press (N) (TVG) NBC4 News Paid Beverly Hills Dog Show Å Hockey 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 In Touch Paid Program News 7 ABC News This Week News NBA Basketball Cleveland Cavaliers at Indiana Pacers. (N) Å Basketball 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Mike Webb Paid Program REAL-Diego Paid 11 FOX In Touch Paid Fox News Sunday News Weird DIY Sci NASCAR NASCAR Racing 13 MyNet Paid Matter Fred Jordan Paid Program Best Buys Paid Program 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 24 KVCR Paint With Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Oil Painting Kitchen Mexico Martha Cooking Baking Sara’s 28 KCET 1001 Nights Bali (TVG) Bali (TVG) Edisons Biz Kid$ Biz Kid$ Migrant Kitchen (10:02) Ed Slott’s Retirement Roadmap 2017 Å 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch White Collar Å White Collar Wanted. White Collar Å White Collar Å 34 KMEX Conexión Paid Program Fútbol Central (N) Fútbol Mexicano Primera División (N) República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN James Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda John Hagee 46 KFTR Paid Program Madeline ››› (1998) Frances McDormand. -

Production Begins on Season 2 of Global's Critically-Acclaimed Mini

PRODUCTION BEGINS ON SEASON 2 OF GLOBAL’S CRITICALLY-ACCLAIMED MINI-SERIES MARY KILLS PEOPLE Canadians Rachelle Lefevre and Ian Lake Join the Cast Alongside Returning Series Stars Caroline Dhavernas, Jay Ryan, and Richard Short The Compelling Drama Joins Global’s Schedule in Winter 2018 “[…] Mary Kills People is a remarkable achievement, balancing so many hues and tones so deftly. It is also very, very entertaining. At times intense and thought-provoking, it is a fascinating excursion to a different realm of comedy/drama.” – The Globe and Mail “Mary Kills People is an energetic, savvy program that combines elements of crime thrillers, medical soaps, and propulsive character drama, employing all those recognizable forms to illuminate the complexity of the knotty issues at its core.” – Variety “But in addition to terrific writing and strong cinematography, the chemistry that [Tassie] Cameron, along with her sister Amy Cameron, brought together with this cast is palpable.” – Sun TV “Mary Kills People is more than its unique premise, with a layered lead performance and consistently entertaining narrative keeping the show's dark comedy grounded in relatable reality.” – Rotten Tomatoes “The writers know that often times you need to laugh to make it through the pain, and they give Mary a wry sense of humor to break up all the death and running from the cops.” – Vulture For photography and press kit materials visit: http://www.corusent.com/ Follow us on Twitter at @GlobalTV_PR To share this release socially: http://bit.ly/2wgRzsj For Immediate Release TORONTO, August 21, 2017 – Canadian broadcast and production partner Corus Entertainment, with Entertainment One (eOne) and Cameron Pictures Inc., are pleased to announce that production has begun on the second cycle of Global’s critically-acclaimed drama Mary Kills People.