The Macintyres of Badenoch Are Descended), Under His Protection.” (3)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BCS Paper 2016/13

Boundary Commission for Scotland BCS Paper 2016/13 2018 Review of Westminster Constituencies Considerations for constituency design in Highland and north of Scotland Action required 1. The Commission is invited to consider the issue of constituency size when designing constituencies for Highland and the north of Scotland and whether it wishes to propose a constituency for its public consultation outwith the electorate quota. Background 2. The legislation governing the review states that no constituency is permitted to be larger than 13,000 square kilometres. 3. The legislation also states that any constituency larger than 12,000 square kilometres may have an electorate lower than 95% of the electoral quota (ie less than 71,031), if it is not reasonably possible for it to comply with that requirement. 4. The constituency size rule is probably only relevant in Highland. 5. The Secretariat has considered some alternative constituency designs for Highland and the north of Scotland for discussion. 6. There are currently 3 UK Parliament constituencies wholly with Highland Council area: Caithness, Sutherland and Easter Ross – 45,898 electors Inverness, Nairn, Badenoch and Strathspey – 74,354 electors Ross, Skye and Lochaber – 51,817 electors 7. During the 6th Review of UK Parliament constituencies the Commission developed proposals based on constituencies within the electoral quota and area limit. Option 1 – considers electorate lower than 95% of the electoral quota in Highland 8. Option 1: follows the Scottish Parliament constituency of Caithness, Sutherland and Ross, that includes Highland wards 1 – 5, 7, 8 and part of ward 6. The electorate and area for the proposed Caithness, Sutherland and Ross constituency is 53,264 electors and 12,792 sq km; creates an Inverness constituency that includes Highland wards 9 -11, 13-18, 20 and ward 6 (part) with an electorate of 85,276. -

The Sinclair Macphersons

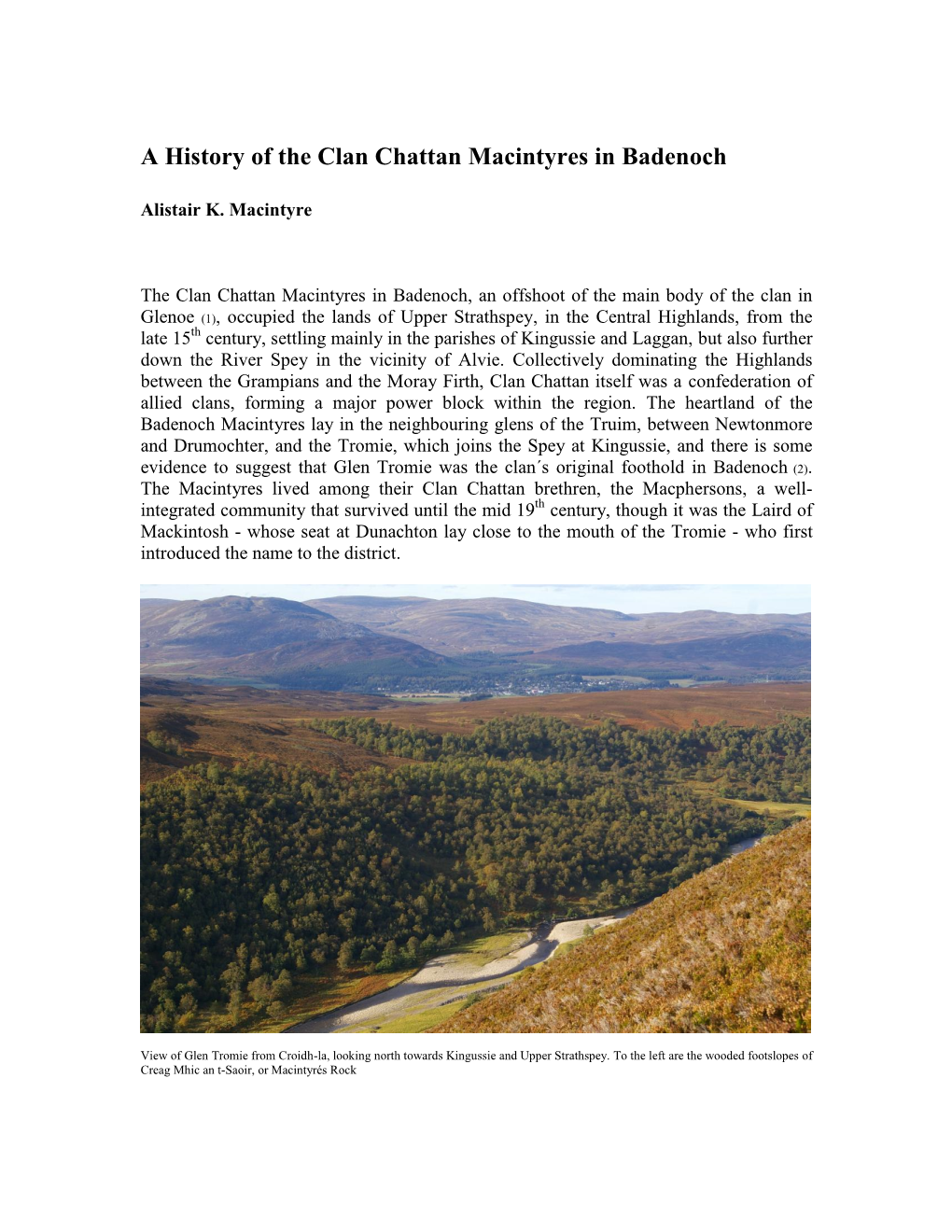

Clan Macpherson, 1215 - 1550 How the Macphersons acquired their Clan Lands and Independence Reynold Macpherson, 20 January 2011 Not for sale, free download available from www.reynoldmacpherson.ac.nz Clan Macpherson, 1215 to 1550 How the Macphersons acquired their traditional Clan Lands and Independence Reynold Macpherson Introduction The Clan Macpherson Museum (see right) is in the village of Newtonmore, near Kingussie, capital of the old Highland district of Badenoch in Scotland. It presents the history of the Clan and houses many precious artifacts. The rebuilt Cluny Castle is nearby (see below), once the home of the chief. The front cover of this chapter is the view up the Spey Valley from the memorial near Newtonmore to the Macpherson‟s greatest chief; Col. Ewan Macpherson of Cluny of the ‟45. Clearly, the district of Badenoch has long been the home of the Macphersons. It was not always so. This chapter will make clear how Clan Macpherson acquired their traditional lands in Badenoch. It means explaining why Clan Macpherson emerged from the Old Clan Chattan, was both a founding member of the Chattan Confederation and yet regularly disputed Clan Macintosh‟s leadership, why the Chattan Confederation expanded and gradually disintegrated and how Clan Macpherson gained its property and governance rights. The next chapter will explain why the two groups played different roles leading up to the Battle of Culloden in 1746. The following chapter will identify the earliest confirmed ancestor in our family who moved to Portsoy on the Banff coast soon after the battle and, over the decades, either prospered or left in search of new opportunities. -

PB/204 1 Local Government and Communities

PB/204 Local Government and Communities Committee Planning (Scotland) Bill Submission from Wildland Limited Established in 2007, Wildland Limited now owns 220,000 acres, spanning three management areas: Badenoch, Sutherland and Lochaber, encompassing some of Highland Scotland’s most rugged and beautiful landscapes. The company has a unique 200 year vision for restoring and transforming the estates in its care by developing a world class portfolio of quality, design-led tourism experiences that allow guests to enjoy the best of Scotland’s hospitality, natural heritage and landscape. Investing £25-30m over the next 3 years, in buildings and property investment alone, its strategy is to build vibrant tourism businesses that support diverse economic opportunities for rural communities, while ensuring that environmental sustainability and conservation lie at the heart of its proposition. With a staff of 59 in Scotland, Wildland Limited will also contribute directly into the communities in which it operates. Wildland Limited has a management board of five who bring a wealth of experience and expertise in the provision of tourism and land resource restoration. Current portfolio Wildland Limited’s three landholdings are; Wildland Cairngorm, Wildland North Coast and Wildland Braeroy and encompass the following estates: Aldourie, Braeroy, Eriboll, Gaick, Glenfeshie, Hope, Killiehuntly, Kinloch, Lynaberack, Loyal and, Strathmore. The company currently operates a diverse range of offerings for visitors to the Highlands looking for extraordinary and unforgettable getaways in scenic locations. These include Kinloch Lodge, Sutherland, Killiehuntly Farmhouse and Cottages, Glenfeshie Estate and Cottages, both within the Cairngorm National Park and Aldourie Castle Estate, Loch Ness. Future growth As a tourism business, Wildland Limited already has a large presence that is growing quickly through targeted investment across its estates. -

Highland Council Area Report

1. 2. NFI Provisional Report NFI 25-year projection of timber availability in the Highland Council Area Issued by: National Forest Inventory, Forestry Commission, 231 Corstorphine Road, Edinburgh, EH12 7AT Date: December 2014 Enquiries: Ben Ditchburn, 0300 067 5064 [email protected] Statistician: Alan Brewer, [email protected] Website: www.forestry.gov.uk/inventory www.forestry.gov.uk/forecast NFI Provisional Report Summary This report provides a detailed picture of the 25-year forecast of timber availability for the Highland Council Area. Although presented for different periods, these estimates are effectively a subset of those published as part of the 50-year forecast estimates presented in the National Forest Inventory (NFI) 50-year forecasts of softwood timber availability (2014) and 50-year forecast of hardwood timber availability (2014) reports. NFI reports are published at www.forestry.gov.uk/inventory. The estimates provided in this report are provisional in nature. 2 NFI 25-year projection of timber availability in the Highland Council Area NFI Provisional Report Contents Approach ............................................................................................................6 25-year forecast of timber availability ..................................................................7 Results ...............................................................................................................8 Results for the Highland Council Area ...................................................................9 -

2019 Scotch Whisky

©2019 scotch whisky association DISCOVER THE WORLD OF SCOTCH WHISKY Many countries produce whisky, but Scotch Whisky can only be made in Scotland and by definition must be distilled and matured in Scotland for a minimum of 3 years. Scotch Whisky has been made for more than 500 years and uses just a few natural raw materials - water, cereals and yeast. Scotland is home to over 130 malt and grain distilleries, making it the greatest MAP OF concentration of whisky producers in the world. Many of the Scotch Whisky distilleries featured on this map bottle some of their production for sale as Single Malt (i.e. the product of one distillery) or Single Grain Whisky. HIGHLAND MALT The Highland region is geographically the largest Scotch Whisky SCOTCH producing region. The rugged landscape, changeable climate and, in The majority of Scotch Whisky is consumed as Blended Scotch Whisky. This means as some cases, coastal locations are reflected in the character of its many as 60 of the different Single Malt and Single Grain Whiskies are blended whiskies, which embrace wide variations. As a group, Highland whiskies are rounded, robust and dry in character together, ensuring that the individual Scotch Whiskies harmonise with one another with a hint of smokiness/peatiness. Those near the sea carry a salty WHISKY and the quality and flavour of each individual blend remains consistent down the tang; in the far north the whiskies are notably heathery and slightly spicy in character; while in the more sheltered east and middle of the DISTILLERIES years. region, the whiskies have a more fruity character. -

Paths with Easy Access Discover Badenoch and Strathspey Welcome to Badenoch and Strathspey! Contents

Badenoch and Strathspey Paths with Easy Access Discover Badenoch and Strathspey Welcome to Badenoch and Strathspey! Contents Badenoch and Strathspey forms an We have added turning points as 1 Grantown-on-Spey P5 important communication corridor options for shorter or alternative Kylintra Meadow Path through the western edge of the routes so look out for the blue Nethy Bridge P7 Cairngorms National Park. The dot on the maps. 2 The Birch Wood Cairngorms is the largest National Park in Britain, a living, working Some of the paths are also 3 Carr-Bridge P9 landscape with a massive core of convenient for train and bus Riverside Path wild land at its heart. services so please check local Carr-Bridge P11 timetables and enjoy the journey 4 Ellan Wood Trail However, not all of us are intrepid to and from your chosen path. mountaineers and many of us 5 Boat of Garten P13 prefer much gentler adventures. Given that we all have different Heron Trail, Milton Loch That’s where this guide will come ideas of what is ‘easy’ please take Aviemore, Craigellachie P15 Easy Access Path, start in very handy. a few minutes to carefully read the 6 Loch Puladdern Trail route descriptions before you set Easy Access Path, The 12 paths in this guide have out, just to make sure that the path turning point been identified as easy access you want to use is suitable for you Central Spread Area Map Road paths in terms of smoothness, and any others in your group. Shows location of the Track gradients and distance. -

The Earldom of Ross, 1215-1517

Cochran-Yu, David Kyle (2016) A keystone of contention: the Earldom of Ross, 1215-1517. PhD thesis. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/7242/ Copyright and moral rights for this thesis are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Glasgow Theses Service http://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] A Keystone of Contention: the Earldom of Ross, 1215-1517 David Kyle Cochran-Yu B.S M.Litt Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Ph.D. School of Humanities College of Arts University of Glasgow September 2015 © David Kyle Cochran-Yu September 2015 2 Abstract The earldom of Ross was a dominant force in medieval Scotland. This was primarily due to its strategic importance as the northern gateway into the Hebrides to the west, and Caithness and Sutherland to the north. The power derived from the earldom’s strategic situation was enhanced by the status of its earls. From 1215 to 1372 the earldom was ruled by an uninterrupted MacTaggart comital dynasty which was able to capitalise on this longevity to establish itself as an indispensable authority in Scotland north of the Forth. -

Housing Application Guide Highland Housing Register

Housing Application Guide Highland Housing Register This guide is to help you fill in your application form for Highland Housing Register. It also gives you some information about social rented housing in Highland, as well as where to find out more information if you need it. This form is available in other formats such as audio tape, CD, Braille, and in large print. It can also be made available in other languages. Contents PAGE 1. About Highland Housing Register .........................................................................................................................................1 2. About Highland House Exchange ..........................................................................................................................................2 3. Contacting the Housing Option Team .................................................................................................................................2 4. About other social, affordable and supported housing providers in Highland .......................................................2 5. Important Information about Welfare Reform and your housing application ..............................................3 6. Proof - what and why • Proof of identity ...............................................................................................................................4 • Pregnancy ...........................................................................................................................................5 • Residential access to children -

Population Change in Caithness and Sutherland 2001 to 2011

THE HIGHLAND COUNCIL Agenda 4. Item CAITHNESS AND SUTHERLAND AREA COMMITTEE Report CS/2/14 No 11TH FEBRUARY 2014 POPULATION CHANGE IN CAITHNESS AND SUTHERLAND 2001 TO 2011 Report by Director of Planning and Development Summary This report looks at the early results from the 2011 Census, giving local information on the number and ages of people living within Highland. It compares these figures with those from 2001 to show that the Highland population has “aged”, and that a large number of people are close to retirement age. The population of Caithness and Sutherland has grown by 3.3% (compared to the Highland average of 11.1%) with an increase in four out of six Wards, and at a local level in 34 out of 58 data zones. Local population growth is strongly linked to the building of new homes. 1. Background 1.1. Publication of the results from the 2011 Census began in December 2012, and the most recent published in November and December 2013 gave the first detailed results for “census output areas”, the smallest areas for which results are published. These detailed results have enabled us to prepare the first 2011 Census profiles and these are available for Wards, Associated School Groups, Community Councils and Settlement Zones on our website at: link to census profiles 1.2. This report returns to some earlier results and looks at how the age profile of the Caithness and Sutherland population and the total numbers have changed at a local level (datazones). These changes are summarised in Briefing Note 57 which is attached at Appendix 1. -

High Points Issue 13 V4.Indd

The Highland Council’s Magazine Spring 2019 Highpoints Issue 13 Sàr Phuingean Performance edition Ambitious, Sustainable, and Connected A vision for Highland www.highland.gov.uk Contents 3 Ambitious for Performance 4 An Ambitious Highland 4 Caol Campus 4 Kingussie Courthouse 5 West Link 5 First Newton Room created Welcome 6 Gaelic Film Awards ‘FilmG’ 7 Housing HUB This edition of Highpoints day cross-party seminar 7 New city homes focuses on performance which considered both the 7 New homes for Ullapool and how we measure up budget and governance of the 7 Iconic mosaic panels return against a range of nationally Council. 8 A Sustainable Highland benchmarked fi gures. 8 Planning Application submitted for MRF There is a positive feeling of 9 Modern Apprentices in the Council The Highland Council is change and members have 10 NW Sutherland School learning together ambitious to be a high really shown the will to work 11 Benefi ts and welfare performing Council and our together with staff to tackle 11 Sustainable ways of working new corporate plan sets out what are huge challenges for 11 Trial air services take off what we want to achieve and the Council. 12 A Connected Highland that we are an ambitious, We identifi ed important key 13 Happy homes for Highland children sustainable and connected themes from our public and 13 Corporate Parenting Board Highland. staff engagement and these 14 Highland Digital connectivity We took a new approach in have helped us develop 14 Your Cash Your Caithness preparing the budget this year. priorities for the Council 15 Invergarry Primary School The Chief Executive, Donna moving forward. -

From the Kingussie Burgh Records

The Railway and the Burgh Building the railway near Kingussie in the early 1860s. At Kingussie there was a small, curious, chattering crowd of people who, however, did not really make us out, but evidently suspected who we were. Grant and Brown kept them off the carriages and gave them evasive answers, directing them to the wrong carriage which was most amusing. Leaves from the Journal of our Life in the Highlands, Queen Victoria, writing about 1861 The remote, and in some respects inaccessible, parts of the Highlands will be opened up to a degree formerly unknown, and will be brought into direct communication with the south. Apart from the immense facilities which the new line will afford to tourists, there can be no doubt that it will have great influence in stimulating industry and trade. Dundee Courier, 11th September 1863 The arrival of the railway to Kingussie in 1863 was a turning point in its history. In only about thirty years it was transformed from a relatively poor and isolated village to a thriving resort town. It was the means by which summer visitors would arrive for their holidays. All manner of goods could now be easily transported in or out. It became the rest stop for trains between Perth and Inverness; a busy refreshments room provided breakfast or dinner baskets, pre-ordered by passengers; local tea ladies kept the troops supplied during the wars. Kingussie station staff circa 1916. A young Duncan MacDonald can be seen in the second row, left. The Badenoch district, being formerly isolated, owes more to the promoters of the railway than any district in the north. -

Meeting with Police 4 November 2003

Scheme THE HIGHLAND COUNCIL Community Services: Highland Area RAUC Local Co-ordination Meeting Job No. File No. No. of Pages SUMMARY NOTES OF MEETING 5 + Appendices Meeting held to Discuss: Various Date/Time of Meeting: 26th April 2018 : 10.00am Issue Date* 11 July 2018 Author Kirsten Donald FINAL REF ACTIONS 1.0 Attending / Contact Details Highland Council Community Services; Area Roads Alistair MacLeod [email protected] Alison MacLeod [email protected] Tom Masterton [email protected] Roddy Davidson [email protected] Kimberley Young [email protected] Mike Cooper [email protected] Highland Council Project Design Unit No attendance British Telecom Duncan MacLennan [email protected] BEAR (Scotland) Ltd Peter McNab [email protected] Scottish & Southern Energy Fiona Geddes [email protected] Scotland Gas Networks No Attendance Scottish Water Darren Pointer [email protected] Apologies / Others Kyle Mackie [email protected] David Johnstone [email protected] Trevor Fraser [email protected] Stuart Bruce [email protected] Ken Hossack – Bear Scotland [email protected] Clare Callaghan – Scottish Water [email protected] 2.0 Minutes of Previous Meetings Discussed works due to be done on Kenneth Street at the end of August. Bear would like copies of traffic management plans and they will send details of their work to Scottish Water. D&E and Stagecoach have been informed of these works and Mike will get in contact with them to discuss in more detail.