John Bradburne(1921-1979)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 August 2021

Catholic Parish of St. Catherine, Penrith, with St. Wulstan’s Chapel, Alston Parish Priest: Fr. John B. Winstanley, St. Catherine’s Rectory, Drovers Lane, Penrith, Cumbria. CA11 9EL T: 01768 862273 E: [email protected] W: www.stcatherinepenrith.org.uk St. Wulstan’s Church, Kings Arms Lane, Alston, Cumbria, CA9 3JF The Haydock Community Centre (restricted bookings only): via parish website, T: 07976 255145, E: [email protected] 1 August 2021 – The 18th Sunday in Ordinary Time, Year B ‘The Lord gave them bread from heaven.’ MASS TIMES & INTENTIONS KEEPING EACH OTHER SAFE: Throughout the Sat 31 9am St. Ignatius of Loyola Mervyn Yamey pandemic it has been made clear that if anyone has any 9.30am - 10am Adoration of the Blessed Sacrament symptoms of Coronavirus they don’t come to church, but & Confessions seek the appropriate medical help. This, of course, remains 5.30pm Confessions at Alston paramount and essential. As we know, cases continue to rise. 6pm at St. Wulstan’s, Alston Infirm Clergy UPDATED GUIDANCE: All parishes have updated their Sun 1 The 18th Sunday in Ordinary Time daily procedures following the government’s entry into Step 8.30am People of the Parish 4 and the guidance received from Bishop Paul and the 10.30am Jim Corcoran Bishops’ Conference. In St. Catherine’s and St. Wulstan’s, Mon 2 St. Peter Julian Eymard No Mass face masks, sanitising hands and air flow are all required. Tue 3 12 noon Sheila Wheaton Signing-in still required on entry. On Sundays at St. Wed 4 Privately St John Vianney Janet Pearson Catherine’s, please fill in the slip on your bench and leave for Thur 5 Dedication of the Basilica of St. -

John Bradburne Prayers

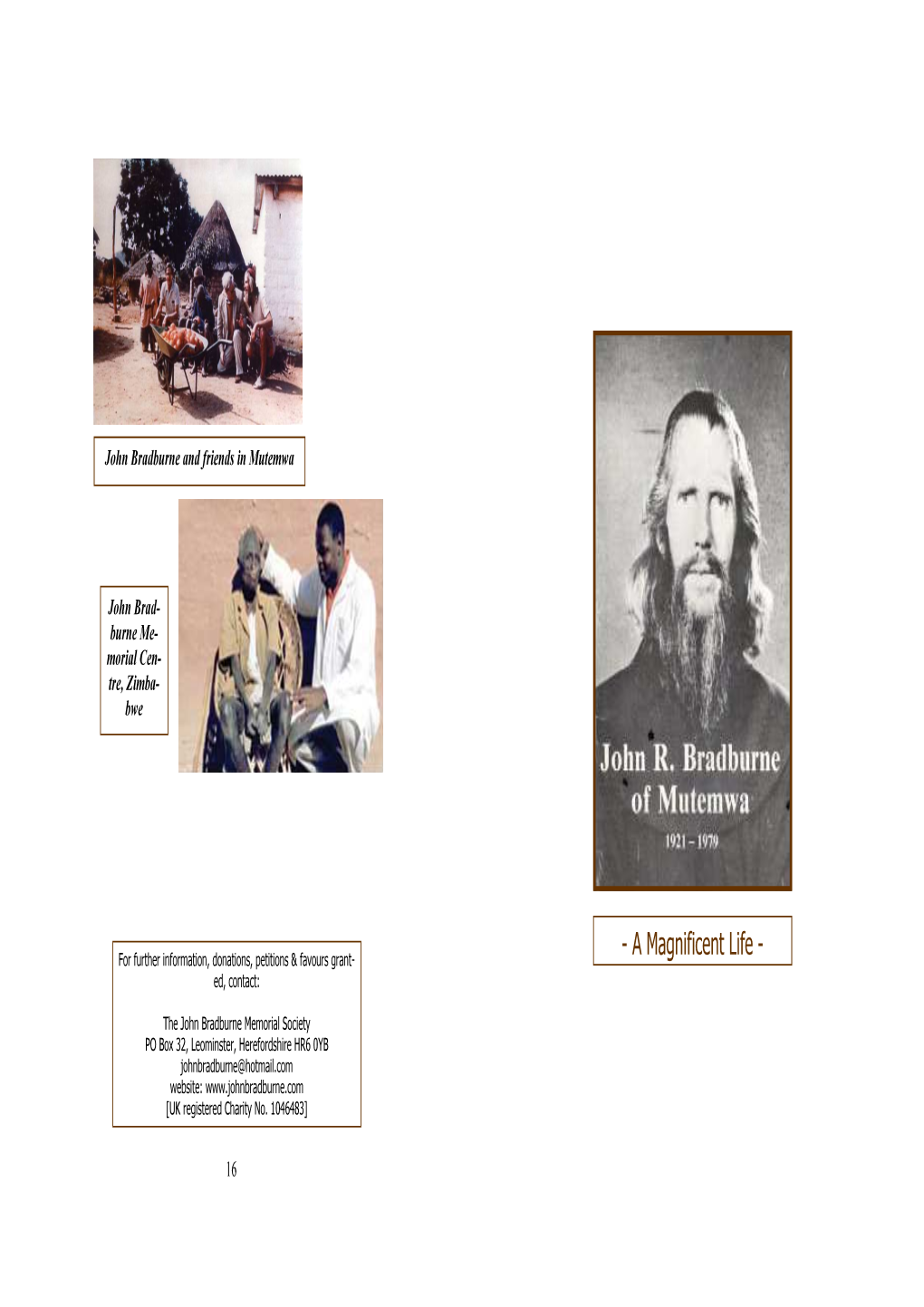

90308 Prayers to John Bradburne A6_Nre John Bradburne Leaflet 30/01/2014 12:25 Page 1 JOHN BRADBURNE John Bradburne Third Order Franciscan, mystic, poet and friend of lepers. Born in England in 1921, he served with the Gurkhas in Malaya and Burma Prayers during World War II. A Pauline-like conversion led him to become a pilgrim seeker, first with the Benedictines, then the Carthusians, but remained a layman to the end. His search for God’s will led him through England, Europe and the Holy Land, mostly on foot. In 1962 he went to “seek a cave” in Zimbabwe. Instead he found Mutemwa Leprosy Settlement. There he tended a flock of 80 leprosy patients with loving care, laying down his life for them on September 5th, 1979. At his funeral, a pool of blood was seen beneath his coffin. On opening it, there was no evidence where the blood had come from. However, an oversight was revealed: John had not been clothed in th e habit of St. Francis, as is the privilege of members of the Third Order, and had been John’s wish. The habit was found and John was clothed in it. Since his death there have been many signs of his sanctity: reports of miracles, claims of cures, as well as many answers to prayer. More important, many have turned to God through John’s extraordinary example. Strange Vagabond “God’s love within you is your native land. So search none other, never more depart. For you are homeless save God keeps your heart.” (JRB) For further information, donations, petitions and favours granted, contact: THE JOHN BRADBURNE MEMORIAL SOCIETY. -

JOHN BRADBURNE – ‘God’S Vagabond’

FREE www.catholicvoiceoflancaster.co.uk The Official Newspaper to INSIDE: p05 Part of History the Diocese of Lancaster p10 Finding Time to Pray Issue 261 + July 2014 p12 A Forgotten Cumbrian Hero he eyes of the world were for three days in May focused on Tthe Holy Land as Pope Francis travelled to area for the first time some 50 years after the Papal visit of Pope Paul VI. Over his three day visit, Pope Francis visited key religious sites and made numerous speeches stressing the need for a lasting peace in lands that have suffered many conflicts throughout Pope Francis history and where divisions still exist today. He said: “I wish to invite you, President Mahmoud Abbas, together with President Shimon Peres, to join me in heartfelt prayer to God for the gift of peace”. “I offer my home in the Vatican as a place for this encounter of prayer”. “All of us want peace. Many people build it day by day through small gestures and acts; many of them are suffering, yet patiently persevere in their efforts to be peacemakers. All of Urges Peace us – especially those placed at the service of their respective peoples – have the duty to become instruments and artisans of peace, especially by our prayers. Building peace is difficult, but living without peace is a constant torment. The men and women of these lands, and of the entire world, all of them, ask us to bring before God their fervent hopes for peace”. President Mahmoud Abbas and President Shimon Peres both accepted the Pope’s invitation and met in the Vatican earlier in June. -

Religious Education Congress Offers

US Bishops Make Virginia Catholics El Papa Inaugura Real Presence The are Helping the en el Vaticano una Focus Homeless Gran Escultura Page 5 Page 14 Page 19 NORTH COAST CATHOLIC The Newspaper of the Diocese of Santa Rosa • www.srdiocese.org • OCTOBER 2019 Noticias en español, pgs. 18-20 Cardinal Levada, former CDF prefect, dies aged 83 Vatican City, Sep 26 (CNA) - Cardinal William Levada, the former prefect of the Congregation for The Annual 2019 Diocesan Religious Education Congress, brings together religion teachers from around the Diocese to the Doctrine of the Faith, died Wednesday, Sept. 25 encourage and equip them for the work of evangelization, and faith formation. at the age of 83. He was the first American to lead the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith (CDF), one of the most senior positions in the Curia. Religious Education Congress Offers Levada was appointed to the position by Pope Bene- dict XVI, who, as Cardinal Ratzinger, had led the Encouragement, Encounter With Jesus congregation until his election as pope. He served in the role from May 13, 2005, until July, 2012. NCC Staff The 2019 Diocese of Santa Rosa Religious Education afraid, this doesn’t end badly, Jesus triumphs in the Congress on September 28th entitled “Encountering end” said Bishop Vasa, as he offered words of strength Jesus in the Liturgy” brought together Religious Edu- to those gathered to reflect on how to reach out to cation leaders and teachers from around the entire our ‘disaffiliated” fellow Catholics who have turned Diocese. Always a big success, this year was especially away from the church for various reasons. -

MISSIONS and MISSIONARY SOCIETIES Biographies 57

3 MISSIONS AND MISSIONARY SOCIETIES Biographies 57 3.1 GENERAL 3.1.2 BIOGRAPHIES, AUTOBIOGRAPHIES, DIARIES, LETTERS, MISSIONARY TRAVELS 3.1.2.1 Collected 374. TANGHE, O. Ons vir jou my swart broer. Brieven, ver- halen en getuigenissen over Vlaamse missionarissen in Zuid- Afrika. Maarkedal: Ceres, 1977. 184p. 375. WILLIAMS, W.L. Black Americans and the evangelization of Africa, 1877-1900. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1982. 259p. Includes Southern Africa. 3.1.2. 2 Individual (arranged alphabetically by biographee) Arnot, F.S. 376. TATFORD, F.A. Frederick Stanley Arnot. /'Bath: Echoes ofServiceJ, 1981. fl8Jp. 3.1.3 GENERAL HISTORIES. ATLASES 377. CHOULES, J.O. & SMITH, T. The origin and history of missions ... Boston: Walker and Lincoln & Edmands, 1830. 2v. Includes missions in South Africa. 378. ENKLAAR, I.H. Korn over en help ons! Twaalf opstellen over der Nederlandse zending in de negentiende eeuw. 's-Gravenhage: Uitgeverij Boekencentrum, 1981. 173p. Includes Van der Kemp's work in South Africa. 58 Missions: General 379. FRESCURA, F. Index of the names of mission stations esta blished in the southern African region during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Johannesburg: Transvaal Vernacular Architecture Society in conjunction with Dept, of Architecture, University of the Witwatersrand, 1982. 97p. 380. HELLBERG, C.-J. A voice of the voiceless: the involvement of the Lutheran World Federation in Southern Africa 1947- 1977. Uppsala: Swedish Institute of Missionary Research, 1979. 236p. (Studia missionalia upsaliensis; 34) 381. JOHANSON, B.A. Ukuqhubeka kweVangeli. 2nd. ed. Sweetwaters, Natal: Union Bible Institute, 1952. 120p. 382. KEYES, L.E. The last age of missions: a study of Third World missionary societies. -

Secular Franciscan Order South East Region

Secular Franciscan Order South East Region ISSUE 23 – ADVENT 2016 Building the Kingdom of God with Living Stones HAVE A BEAUTIFUL, PEACEFUL AND HAPPY CHRISTMAS and 2017!! A PRAYER OF ST FRANCIS A prayer for Assisi - MERCY When Francis felt his death was approaching, he had himself carried on a litter to the church of St Mary of the Angels, wishing to die there where his new life had begun. On the way he asked the bearers to make a short halt and, having himself turned towards the town of Assisi, which on account of his blindness he could no longer descry, he uttered the following prayer: Lord, As in days gone by many evil-doers lived in this city, so now I see it has pleased your abundant mercy to show this city the fullness of your grace. May it become a dwelling and a home for all who acknowledge you and seek to glorify your name forever and ever; For all who give an example of virtuous life and witness of true doctrine to all Christendom. I therefore beg you, Lord Jesus Christ, Father of mercies, not to consider our ingratitude but ever to be mindful of your abundant mercy which you have displayed here. (Mirror of Perfection 124) 1 Dear brothers and sisters Recently, at the start of October, we had a wonderful day together at Erith, and something that struck me very much that day was the great value in meeting together as a region and what a wonderful group of people we have in our region. -

17Th Sunday of Ordinary Time 30Th

PARISH OF OUR LADY IMMACULATE, WESTBOURNE Roman Catholic Diocese of Portsmouth: registered charity 246871 visit us at catholicwestbourne.org RECOMMISSIONING ORGANIST: Do you know anyone who on Saturday 12th August at noon and OF EXTRAORDINARY would be interested in being our church at 3pm, and Sunday 13th August at MINISTERS OF HOLY organist? An understanding and love of 3pm. COMMUNION: Will take place today the liturgy essential. Please contact the during 9am and 11am Masses. parish office for further information. ROSARIES FOR PRISONERS: The Catenians are currently FR. TONY PENNICOTT: Today is Fr. SECOND COLLECTION: None today, collecting white plastic rosaries Tony’s last Sunday with us for a while. nor next week. to meet demand for them However, he will continue to offer among Catholic prisoners. If you can Mass on Fridays up until September, CHURCH CLEANING: 2pm on August help, please send rosaries to: Michael and also stand in whenever Fr. An- 14th and September 4th. New volun- Blackburn, 164 Green Park Road, drew is away. We are so very grateful teers always welcome. Halifax HX3 0SP. For further infor- to him for his continued stable influ- mation, call 01422 352559 or email ence on the parish during this year of [email protected] transition. PASTORAL AREA AND BEYOND JOHN BRADBURNE AND THE SUNDAYS IN AUGUST: Fr. Peter MUTEMWA LEPER COLONY, Edwards and Fr. Dominic Jacob from FATIMA RELICS TO VISIT ZIMBABWE: A talk by Reverend Ben the Oratorian community at the Sacred PORTSMOUTH CATHEDRAL: Bradshaw about John Bradburne who Heart, Bournemouth, will be celebrat- During this Centenary Year, the spent many years in total dedication to ing Masses here at OLI during the World Apostolate of Fatima statue of Our a leprosy colony. -

Jbms Newsletter

Text Winter2013_Layout 1 07/11/2013 14:22 Page 1 JBMS NEWSLETTER Published by The John Bradburne Memorial Society PO Box 32, Leominster, Herefordshire HR6 0YB, UK Tel: 01568 760632 e-mail: [email protected] website www.johnbradburne.com UK Registered Charity No. 1046483 WINTER 2013 BIG THANK YOU TO FRIENDS AND BENEFACTORS Huge gratitude goes to extend the existing one, the manpower and the skills out to all those who have which will mean a larger pro- are all there. So I think these continued their support to duction of eggs and poultry projects will be a blessing for help keep our work going this meat to provide home grown them. Since there are thou- year at Mutemwa. food with the excess sold at sands of people who visit markets nearby. It has greatly Mutemwa every year, the We would especially like helped to provide the resi- news will soon get round. to thank The Leper League in dents with new incentives, Here is a place that can run Birmingham for their wonder- and pride in what they can itself. ful support for projects at achieve at the Centre. Mutemwa, and also to the It is obvious that Africa Australian ‘Zimbabwe Chal- Tim and Jean Dufton sent must go solar. We have bright lenge’ team. The sustainable these photographs recently of sunshine more than 300 days way forward for Mutemwa is their visit to Mutemwa to see of the year. The problem has to strive to develop self-sus- the work in progress. been how to harness the taining and income generat- A new solar installation power. -

4 October 2020

Registered Charity no. 1131090 4 October Listening to Fr Nicolas CR (when he 2020 was visiting us last month), talk about Dedication John Bradburne (1921–1979), who Festival / cared for lepers in Zimbabwe and who Trinity 17 was martyred there, ‘He had few possessions, only love’, reminded me of Welcome to the saint, whose day it is today; Francis St Barnabas’ in Pound Hill and of Assisi (1182–1226). St Nicholas’ in Worth Bradburne, known as a pilgrim, hermit, This sheet details the readings in today’s poet, musician, joker, mystic, and services as well as notices for everyone. theologian, dedicated his life to follow Please do take it home and share it. the way of St Francis. Like him, he If you are here for the first time, please enriched the church by his poverty and introduce yourselves. was generally thought to be crazy. Almost everything Francis did was There are soft toys and books available for interpreted by someone as a sign that children. he had lost his mind. Francis didn’t argue with them. He openly admitted SERVICES TODAY that he was a fool, but not just any kind of fool. He was fool enough to believe 08:00 Holy Communion (BCP) St Nicholas’ that Jesus actually meant his disciples to Celebrant & Preacher Revd Gordon Parry live as he had instructed. ‘Sell what you 10:00 Said Eucharist St Barnabas’ own, and give the money to the poor, Celebrant & Preacher Revd Francis Pole and you will have treasure in heaven; then come, follow me.’ Francis heard 10:15 Said Eucharist & Blessing St Nicholas’ and followed the call of Jesus to seek Celebrant & Preacher Bishop Martin first God’s Kingdom and God’s righteousness, God's justice. -

Stratton St Margarets Abstracts of Inclosure Awards and Agreements Award 19 Sept

Stratton St Margarets Abstracts of Inclosure Awards and Agreements Award 19 Sept. 1796, enrolled 19 June 1798 Wiltshire Records Society Edited by (formerly the Records Branch of the Wiltshire Archaeological and R. E. Sandall Natural History Society) Devizes 1971 Volume XXV © Wiltshire Record Society 1971 for the year 1969 SBN: 901333 02 6 Abstracts of Wiltshire Inclosure Awards and Agreements Commissioners Richard Richardson of Bath, Francis Webb of Salisbury, Richard Davis of Lewknor, Oxon. Surveyor William Tubb of Fisherton Anger. Lord of Manor Of Stratton. Ambrose Goddard of Corsham, Paul Cobb Methuen. Rector Warden and scholars of Merton College, Oxford. Vicar James Hare. Area [1.836 a.] Upper, Middle and Long Field, Redlands Field, Ryall Farm; Stratton Marsh, Cow Common, Flaxlands, Hatmoor Pond, Clay Field, Stanhill Field, The Barrow, Blindmore Field, Great and Little Sturry Field, Shiplands Field, Little Peaks, Hay Field, Catsbrain, Dunge Furlong. © Wiltshire OPC Project / 2015 / John Pope Page 1 of 3 Allotments 64. Public: 6 allotments for roads. Warden and Scholars of Merton 482 a. including lease William Croome 482 a. for glebe and College, Oxford tithes Paul Cobb Methuen 180 a. including copy. Edward Byrchell 24 a. Lucy Gray 42 a. William Croome 77 a. Other names mentioned in this part of the document. John Kempster, Richard Kempster, Thomas North, Richard Looker, Richard Read, Benjamin Richardson, James White John Blandy 53 a. Sarah Haggard 136 a. William Tomkins 42 a. John Bradburne 97 a. John Herring 26 a. James White 26 a. Edward Byrchall 40 a. John Hitchman 50 a. Jane Carpenter 29 a. Philip and Robert Hyatt 17 a. -

John Bradburne

John Bradburne John Bradburne: Mystic, Poet and Martyr (1921-1979) Edited by Renato Tomei John Bradburne: Mystic, Poet and Martyr (1921-1979) Edited by Renato Tomei This book first published 2018 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2018 by Renato Tomei and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-0778-5 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-0778-4 I love this inability to end Ever without just adding one more verse, It seems to me a sempiternal trend For blending with The One is none the worse Even for endless aeons unbegun, To wit: God - Holy Spirit, Father, Son. (From ‘L’ensuite’, 1974) CONTENTS Preface ........................................................................................................ ix Chapter One ................................................................................................. 1 John Bradburne: A Life in Words David Crystal Chapter Two .............................................................................................. 14 The Hero of a Mystic Life Didier Rance Chapter Three ............................................................................................ 34 John -

5Th January, 2020 - Year A

Teaching our FAMILIES to teach their families THE FAITH 5th January, 2020 - Year A The EPIPHANY of the LORD ALL HALLOWS’ Dear Parishioners, PARISH CHURCH 1. Parish Hours over January. 2 Halley Street The parish will be closed from 20th December to 2nd January, 2020 at FIVE DOCK 2046 reduced hours. Administrator: The parish will be manned between the hours of 9.30am and 12.30pm Fr Matthew Solomon on the following days Assistant Priest: 7th, 9th, 14th, 16th, 21st and 23rd January. Fr Nicholas Rynne Elsa will return to the office on 29th January, 2020 Deacon: Rev. Mr. Constantine Rodrigues [email protected] God Bless Fr Matthew. Secretary: Elsa Waldie Welcome to the 2020s: What Catholics can expect in the next dec- Presbytery: ade Monday: Closed Tues - Fri: 8.30am - 3.30pm Closed for lunch 12.30-1.30 pm What will happen to the Church in the coming decade? Only God Phone: 9713 7960 knows, but it’s still worth considering what may lie ahead in the 2020s. Fax: 9713 5172 Here are 10 things that might happen in the next 10 years – some more Email: likely than others. [email protected] Web: www.allhallows.org.au Demographic change If current trends continue, the Church will grow by roughly 15 million All Hallows’ Parish School souls a year, taking the total number of Catholics beyond the 1.4 billion mark by the end of the 2020s (the highest figure in history). Most of the Principal: Mrs Helen Elliott growth will be in Africa and Latin America, with some two million more Phone: 9713 4469 Fax: 9712 5184 Catholics each year in Asia.