Acevo Briefing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DWP Work Programme PDF 108 KB

WIRRAL Council REGENERATION & ENVIRONMENT POLICY & PERFORMANCE COMMITTEE 3RD DECEMBER 2014 SUBJECT: DWP WORK PROGRAMME WARDS AFFECTED: ALL REPORT OF: STRATEGIC DIRECTOR OF REGENERATION & ENVIRONMENT RESPONSIBLE PORTFOLIO COUNCILLOR PAT HACKETT HOLDER 1.0 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1.1 This report provides Members with information on the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) Work Programme launched throughout Great Britain in June 2011. Locally DWP has contracted with two ‘prime’ contractors (A4E and Ingeus) to deliver this provision which aims to support local people in receipt of DWP benefits into sustainable employment. The report will provide the latest performance data for delivery in Wirral as published by DWP and will seek to provide comparators where available. 2.0 BACKGROUND 2.1 The DWP Work Programme introduced in June 2011 is a nationally contracted programme which has rolled out a payment by results model on a large scale, where Prime Contractors are paid on sustainable job outcomes. The payments are designed to incentivise the contractors to work with the full range of benefit claimants with larger payments on securing job outcomes and ongoing payments for up to two years for those furthest from the labour market. All referrals to the Work Programme are through Jobcentre Plus. There are different thresholds for referrals to the Work Programme depending on age and benefit type. 2.2 DWP contract with providers over large geographical areas known as Contract Package Areas (CPA) with Wirral being part of the Merseyside, Halton, Cumbria & Lancashire CPA. The payment group for a claimant is the group that Jobcentre Plus assigns the claimant to, on the basis of the benefit they receive. -

Bridges Into Work Overview

The Bridges into Work project started in January 2009. Its aim is to support local people gain the skills and confidence to help them move towards employment. The project is part funded by the Welsh European Funding Office across 6 local authorities in Convergence areas of South Wales – Merthyr Tydfil , Rhondda Cynon Taf, Torfaen, Blaenau Gwent, Bridgend and Caerphilly. In Merthyr Tydfil the project is managed and implemented by Merthyr Tydfil County Borough Council, which has enjoyed massive success with its recent venture The Neighbourhood Learning Programme. It has helped to engage local people to secure full time employment and to progress onto further learning in recent years. Carrying on from the achievement is the Neighbourhood Learning Centre, Gurnos and the newly established Training Employment Centre in Treharris. Both centres seek to engage with local people from all parts of Merthyr Tydfil and fulfil the Bridges into Work objective of providing encouragement, training, advice and guidance for socially excluded people with the view to get them back into work. The Neighbourhood Learning Centre has a range of training facilities covering a variety of sectors including plumbing, painting and decorating, carpentry, bricklaying, plastering, retail, customer service and computer courses. There are a team of experienced tutors who deliver training for local people within the community. Bridges into Work successfully delivered a Pre-Employment course for Cwm Taf Health Trust to recruit Health Care Assistants. With the help and support of the Neighbourhood Learning Pre-Employment Partnership fronted by the Bridges into Work Programme which includes organisations such as Voluntary Action Merthyr Tydfil, Remploy, Working Links, Shaw Trust, A4E, JobCentre Plus and JobMatch successfully provided and supported participants interested in becoming Health Care Assistants. -

A4e Ltd Independent Learning Provider

Further Education and Skills inspection report Date published: June 2015 Inspection Number: 461179 URN: 50083 A4e Ltd Independent learning provider Inspection dates 18–22 May 2015 This inspection: Good-2 Overall effectiveness Previous inspection: Requires improvement-3 Outcomes for learners Good-2 Quality of teaching, learning and assessment Good-2 Effectiveness of leadership and management Good-2 Summary of key findings for learners This provider is good because: . the majority of learners receive good support to overcome multiple barriers to achieve their qualifications . learners develop good personal, social and employability skills that prepare them well for work . effective initiatives with major employers help learners find employment . senior managers work effectively with Local Enterprise Partnerships to redesign the curriculum to meet regional skills’ shortages . English and mathematical skills are successfully developed through their practical application in realistic vocational settings . pre-course information, advice and guidance are good and, coupled with thorough initial assessment, ensure that learners are placed and retained on the right courses . equality of opportunity is skilfully promoted, and through carefully planned activities, learners develop a good understanding of life in a diverse society . board members and senior managers have worked successfully and quickly to address the majority of the areas for improvement identified at the last inspection . performance management of staff and the use of management information are effective and enable managers to drive improvements in all areas of delivery. This is not yet an outstanding provider because: . not enough apprentices achieve their qualifications on time . written feedback is not sufficiently detailed, and targets are not always specific enough to inform learners what they need to do to progress . -

Econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Maddock, Su Working Paper A MIOIR case study on public procurement and innovation: DWP work programme procurement - Delivering innovation for efficiencies or for claimants? Manchester Business School Working Paper, No. 629 Provided in Cooperation with: Manchester Business School, The University of Manchester Suggested Citation: Maddock, Su (2012) : A MIOIR case study on public procurement and innovation: DWP work programme procurement - Delivering innovation for efficiencies or for claimants?, Manchester Business School Working Paper, No. 629, The University of Manchester, Manchester Business School, Manchester This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/102375 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur -

Adult Training Network

ADULT TRAINING NETWORK ATN REPORT FOR THE PERIOD AUGUST 2013 – JULY 2014 1 | P a g e Adult Training Network Annual Report 2013-2014 Contents Page Organisational Details 3 Mission Statement 3 Aims & Objectives 3 Company Structure 4 Training Centres 5 Business Plan & Aims and Objectives 6 - 7 Company Accounts 7 Staffing Establishment 7-8 Staff Development & Training 8 - 10 Partnership Agreements 10 Accreditation 11 Activities 2013 – 2014 11 -18 Richmond upon Thames College 10 – 14 Waltham Forest College 14 – 15 A4e - JCP Support Contract 16 A4e Professional and Executive and Graduate Programme 16 - 17 Ingeus Work Programme – Routeway Provider 17 Reed in Partnership – Work Programme Pilot 18 G4s – Community Work Placements (CWP) Programme 18 Reed – ESF Families Programme 19 Matrix Accreditation 19 External Verification & Inspection Reports 19-22 Extension Activities 22 -27 Good news stories & Case Studies 27-31 Future Developments & Priorities 31 Conclusion 32 2 | P a g e Adult Training Network Annual Report 2013-2014 ORGANISATIONAL DETAILS The Adult Training Network is a Registered Charity Number 1093609, established in July 1999, and a Company Limited by Guarantee number 42866151. The Head Office is at Unit 18, Arches Business Centre, Merrick Road, Southall, Middlesex, UB2 4AU. The Adult Training Network has a Board of Trustees and a Managing Director, who is the main contact person for the organisation. Further information on the Adult Training Network can be found on the organisation’s website at http://www.adult-training.org.uk. The Chair of the Board of Trustees is Mr Pinder Sagoo and the Managing Director is Mr Sarjeet Singh Gill. -

Work Programme Supply Chains

Work Programme Supply Chains The information contained in the table below reflects updates and changes to the Work Programme supply chains and is correct as at 30 September 2013. It is published in the interests of transparency. It is limited to those in supply chains delivering to prime providers as part of their tier 1 and 2 chains. Definitions of what these tiers incorporate vary from prime provider to prime provider. There are additional suppliers beyond these tiers who are largely to be called on to deliver one off, unique interventions in response to a particular participants needs and circumstances. The Department for Work and Pensions fully anticipate that supply chains will be dynamic, with scope to flex and evolve to reflect change within the labour market and participant needs. The Department intends to update this information at regular intervals (generally every 6 months) dependant on time and resources available. In addition to the Merlin standard, a robust process is in place for the Department to approve any supply chain changes and to ensure that the service on offer is not compromised or reduced. Comparison between the corrected March 2013 stock take and the September 2013 figures shows a net increase in the overall number of organisations in the supply chains across all sectors. The table below illustrates these changes Sector Number of organisations in the supply chain Private At 30 September 2013 - 367 compared to 351 at 31 March 2013 Public At 30 September 2013 - 128 compared to 124 at 30 March 2013 Voluntary or Community (VCS) At 30 September 2013 - 363 compared to 355 at 30 March 2013 Totals At 30 September 2013 - 858 organisations compared to 830 at March 2013. -

Social Mobility Business Compact List of Signatories A4E Aberdeen Asset

This list has been withdrawn and replaced: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/social-mobility-business-compact-list-of-signatories Social Mobility Business Compact List of signatories A4E Aberdeen Asset Management PLC ACCA Accenture Acorn Environment Addleshaw Goddard LLP Adecco Group UK & Ireland AGR Airbus Allen and Overy Alliance Boots Anchor Trust AOL Arriva Asda Ashurst LLP Aspire Group Associated Newspapers Association of Accounting Technicians (AAT) Aston University Atkins Aviva plc AXA BAE Systems Baker & McKenzie LLP Bank of America Merrill Lynch Bank of England Bar Council Barcelo Hotels UK Barclays Bauer Media Group BBC Be Wiser Insurance Ltd BP British Land BSkyB BT Group Cabinet Office Cancer Research UK Capgemini Capita Capp & Co Ltd Carillion This list has been withdrawn and replaced: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/social-mobility-business-compact-list-of-signatories Caterpillar Centrica Channel 4 Charted Institute of Public Relations Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development (CIPD) Chartered Insurance Institute CH2M Hill Citi City and Guilds City of London Corporation Clifford Chance CMS Cameron McKenna LLP Coca Cola Enterprises Coca Cola Great Britain Compass Group Credit Suisse Crown Prosecution Service Dell Deloitte Department for Business, Innovation and Skills Department for Communities and Local Government Department for Education Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs Department for International Development Department for Transport Department for Work and Pensions Department -

The Work Programme: Factors Associated with Differences in the Relative Effectiveness of Prime Providers

The Work Programme: factors associated with differences in the relative effectiveness of prime providers August 2016 The Work Programme: factors associated with differences in the relative effectiveness of prime providers DWP ad hoc research report no. 26 A report of research carried out by NIESR on behalf of the Department for Work and Pensions. © Crown copyright 2016. You may re-use this information (not including logos) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence. To view this licence, visit http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU,or email: [email protected]. This document/publication is also available on our website at: https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/research-reports If you would like to know more about DWP research, please email: [email protected] First published 2016. ISBN 978-1-78425-617-3 Views expressed in this report are not necessarily those of the Department for Work and Pensions or any other Government Department The Work Programme: factors associated with differences in the relative effectiveness of prime providers Summary The Work Programme is delivered by 18 private, public and voluntary sector organisations, working under contract to DWP. These organisations are known as prime providers, or "primes", and operate within a geographical Contract Package Area (CPA). Each CPA has either two or three primes and individuals entering the Work Programme are randomly assigned to one of these. Comparing the outcomes of individuals assigned to each prime within a CPA provides robust estimates of relative effectiveness. -

Prime Provider Contact Details by Contract Package Area – Work Programme (September 2012)

www.dwp.gov.uk/policy/welfare-reform/the-work-programme Prime provider contact details by contract package area – Work Programme (September 2012) Contract Package Contract Package Preferred bidders Contact Contact details Area Number Area 1 East of England Ingeus Deloitte James Weait [email protected] 07917436580 Seetec Chris Shawyer [email protected] 07977 294535 2 East Midlands Ingeus Deloitte Mark Gilbert [email protected] 07769168299 A4e Mandy Cutler [email protected] 077843038506 3 London 1 Ingeus Deloitte Ronan Smyth [email protected] 07812203492 Reed Donna Murrell [email protected] 020 7619 9469 Maximus Athina Ioannidis [email protected] 4 London 2 CDG Renae Lowry [email protected] 07824 642926 Seetec Andrew Emerson [email protected] 07977 002278 A4e Fran Hoey [email protected] 07872423477 5 North East Ingeus Deloitte Allyson Donohoe [email protected] 07557561489 WITHDRAWN Avanta Craig Drummond [email protected] 07500 795018 6 North West 1 Ingeus Deloitte Faith King [email protected] 07557563335 A4e Anthony [email protected] Cavanagh 07717767033 DWP – July 2013 www.dwp.gov.uk/policy/welfare-reform/the-work-programme Contract Package Contract Package Preferred bidders Contact Contact details Area Number Area 7 North West 2 G4S George Selmer [email protected] 0161 618 1792 Avanta Robert Taylor [email protected] 07814491001 Seetec Debra Fullerton [email protected] 0161 236 8964 8 Scotland Working Links Nick Young [email protected] -

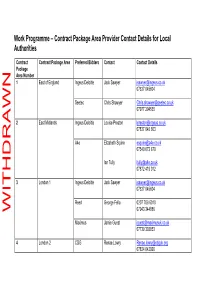

Work Programme – Contract Package Area Provider Contact Details for Local Authorities

Work Programme – Contract Package Area Provider Contact Details for Local Authorities Contract Contract Package Area Preferred Bidders Contact Contact Details Package Area Number 1 East of England Ingeus Deloitte Jack Sawyer [email protected] 07837 045604 Seetec Chris Shawyer [email protected] 07977 294535 2 East Midlands Ingeus Deloitte Louise Preston [email protected] 07837 045 603 A4e Elizabeth Squire [email protected] 07540 673 670 Ian Tully [email protected] 07872 419 012 3 London 1 Ingeus Deloitte Jack Sawyer [email protected] 07837 045604 Reed George Fella 0207 708 6010 07943 344886 WITHDRAWN Maximus Jamie Guest [email protected] 07739 302853 4 London 2 CDG Renae Lowry [email protected] 07824 642926 Seetec Andrew Emerson [email protected] 07977 002278 A4e Jenny Smith [email protected] 07540 673678 Mark Roberts [email protected] 07545 423 778 5 North East Ingeus Deloitte Neil Johnson [email protected] 07557 281648 Avanta Kaye Rideout [email protected] (Regional Director) 07590 418294 6 North West 1 Ingeus Deloitte Barry Fletcher [email protected] 07800 624722 A4e Rhys Harris [email protected] 07872 424 457 Di Ainsworth [email protected] 07880 786707 7 North West 2 G4S George Selmer [email protected] 0161 618 1792 WITHDRAWN Avanta Marie Murray– [email protected] Henderson (Regional 07872 502912 Director) Amanda Stewart [email protected] (Regional Director) 07971 248945 Seetec Debra Fullerton [email protected] 0161 236 8964 8 -

The Introduction of the Work Programme

House of Commons Committee of Public Accounts Department for Work and Pensions: the introduction of the Work Programme Eighty–fifth Report of Session 2010– 12 Report, together with formal minutes, oral and written evidence Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 25 April 2012 HC 1814 Published on 15 May 2012 by authority of the House of Commons London: The Stationery Office Limited £12.00 Committee of Public Accounts The Committee of Public Accounts is appointed by the House of Commons to examine ‘‘the accounts showing the appropriation of the sums granted by Parliament to meet the public expenditure, and of such other accounts laid before Parliament as the committee may think fit’’ (Standing Order No 148). Current membership Rt Hon Margaret Hodge (Labour, Barking) (Chair) Mr Richard Bacon (Conservative, South Norfolk) Mr Stephen Barclay (Conservative, North East Cambridgeshire) Jackie Doyle-Price (Conservative, Thurrock) Matthew Hancock (Conservative, West Suffolk) Chris Heaton-Harris (Conservative, Daventry) Meg Hillier (Labour, Hackney South and Shoreditch) Mr Stewart Jackson (Conservative, Peterborough) Fiona Mactaggart (Labour, Slough) Mr Austin Mitchell (Labour, Great Grimsby) Chloe Smith (Conservative, Norwich North) Nick Smith (Labour, Blaenau Gwent) Ian Swales (Liberal Democrats, Redcar) James Wharton (Conservative, Stockton South) The following Members were also Members of the committee during the parliament: Dr Stella Creasy (Labour/Cooperative, Walthamstow) Justine Greening (Conservative, Putney) Joseph Johnson (Conservative, Orpington) Eric Joyce (Labour, Falkirk) Rt Hon Mrs Anne McGuire (Labour, Stirling) Powers The committee is one of the departmental select committees, the powers of which are set out in House of Commons Standing Orders, principally in SO No 152. -

Pathways to Work for Incapacity Benefit Claimants

New Labour, Welfare Reform and Conditionality: Pathways to Work for Incapacity Benefit Claimants Aimee Grant Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Social Sciences, Cardiff University, 2011 New Labour, Welfare Reform and Conditionality: Pathways to Work for Incapacity Benefit Claimants Aimee Grant Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Social Sciences, Cardiff University, 2011 UMI Number: U5670B7 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U567037 Published by ProQuest LLC 2013. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Abstract This thesis is an exploration of New Labour’s approach to Incapacity Benefit (IB) claimants, and is primarily concerned with ‘Pathways to Work, a policy piloted in 2002 and rolled out nationally in 2007. Pathways, as it is commonly referred to, introduced a requirement for new IB claimants to attend compulsory Work Focused Interviews (WFIs) with a Jobcentre Plus Advisor. Furthermore, the claimants were to be offered support in the form of a range of voluntary work-focused initiatives. The most innovative of these was the Condition Management Programme (CMP), which was funded by the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) but delivered by the NHS, primarily by Occupational Therapists.