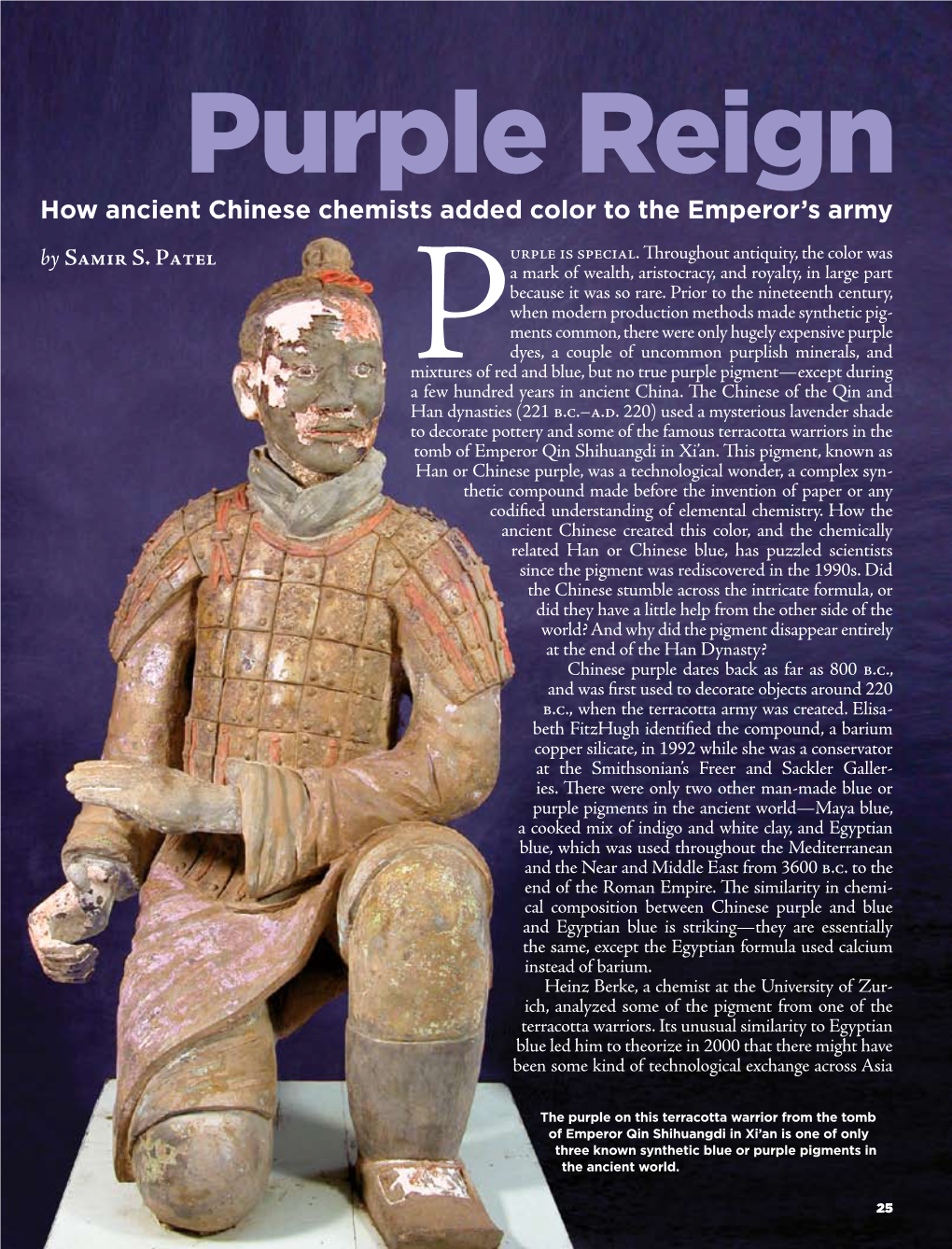

Purple Reign: How Ancient Chinese Chemists Added Color to the Emperor's Army

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pale Intrusions Into Blue: the Development of a Color Hannah Rose Mendoza

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2004 Pale Intrusions into Blue: The Development of a Color Hannah Rose Mendoza Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF VISUAL ARTS AND DANCE PALE INTRUSIONS INTO BLUE: THE DEVELOPMENT OF A COLOR By HANNAH ROSE MENDOZA A Thesis submitted to the Department of Interior Design in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts Degree Awarded: Fall Semester, 2004 The members of the Committee approve the thesis of Hannah Rose Mendoza defended on October 21, 2004. _________________________ Lisa Waxman Professor Directing Thesis _________________________ Peter Munton Committee Member _________________________ Ricardo Navarro Committee Member Approved: ______________________________________ Eric Wiedegreen, Chair, Department of Interior Design ______________________________________ Sally Mcrorie, Dean, School of Visual Arts & Dance The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii To Pepe, te amo y gracias. iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I want to express my gratitude to Lisa Waxman for her unflagging enthusiasm and sharp attention to detail. I also wish to thank the other members of my committee, Peter Munton and Rick Navarro for taking the time to read my thesis and offer a very helpful critique. I want to acknowledge the support received from my Mom and Dad, whose faith in me helped me get through this. Finally, I want to thank my son Jack, who despite being born as my thesis was nearing completion, saw fit to spit up on the manuscript only once. -

Origin of the Exotic Blue Color of Copper-Containing Historical

Article pubs.acs.org/IC Origin of the Exotic Blue Color of Copper-Containing Historical Pigments Pablo García-Fernandez,́ * Miguel Moreno, and JoséAntonio Aramburu Departamento de Ciencias de la Tierra y Física de la Materia Condensada, Universidad de Cantabria, Avenida de los Castros s/n, 39005 Santander, Spain *S Supporting Information ABSTRACT: The study of chemical factors that influence pigment coloring is a field of fundamental interest that is still dominated by many uncertainties. In this Article, we investigate, by means of ab initio calculations, the origin of the unusual bright blue color displayed by historical Egyptian Blue (CaCuSi4O10) and Han Blue (BaCuSi4O10) pigments that is surprisingly not found in other 6− compounds like BaCuSi2O6 or CaCuO2 containing the same CuO4 chromophore. We show that the differences in hue between these systems are controlled by a large red-shift (up to 7100 cm−1) fi 6− produced by an electrostatic eld created by a lattice over the CuO4 chromophore from the energy of the 3z2-r2 → x2-y2 transition, a nonlocal phenomenon widely ignored in the realm of transition metal chemistry and strongly dependent upon the crystal structure. Along 4− this line, we demonstrate that, although SiO4 units are not involved in the chromophore itself, the introduction of sand to create CaCuSi4O10 plays a key role in obtaining the characteristic hue of the Egyptian Blue pigment. The results presented here demonstrate the opportunity for tuning the properties of a given chromophore by modifying the structure of the insulating lattice where it is located. ■ INTRODUCTION even then they remained rare. -

Prolific Pigmentfinal4.19.20 Copy

Proliic pigment Create your own unique color! Summary: Throughout history, people have used pigment to express them- selves. How do you make a pigment and what could you use it for? What kind of paint can you create using pigments found at home? Guiding Questions: What are pigments? Where do pigments come from? What could you use pigments for? Experience Goals: • Explore how pigments are made and used. • Make your own pigment and turn it into paint. Supplies: • Pigment Info Sheet • Fresh or Freeze-dried Blueberries (pigment material) • Water (binding material) • Coloring sheet (page 5) • Paintbrush and paint cup • Mortar and Pestle (or another grinding tool, like a bowl and large spoon) • A space you can get messy in! 1. Steps: 1. Explore Pigments a. Explore the Pigment Info Sheet to learn about pigment and how it is used. b. Think about what could create pigment in your home. Is there anything in your kitchen? How about colorful plants outside? c. We will use blueberries to make our color! You can ind the recipe in Step 3. What other colors could you create? What would you paint with them? 2. Make Your Pigment a. Gather your pigment material. Usually a pigment used in painting will be powdered, but can also be in juice form. Crushed up freeze dried fruits like blueberries make for an excellent pigment powder! b. Grind or mash up your pigment material. If using fresh blueberries, mash them then strain out the juice using a kitchen strainer. With frozen or freeze dried blueberries, use a mortar and pestle (or similar items like a bowl and large spoon) to grind them into a ine powder. -

PAINTING BEYOND the PHOTO (P-16) Laura Spector Intermediate / Advanced Monday Evening, 6:30 - 9:30 PM January 22, 29 and February 5, 12 4-Day Workshop

PAINTING BEYOND THE PHOTO (P-16) Laura Spector Intermediate / Advanced Monday evening, 6:30 - 9:30 PM January 22, 29 and February 5, 12 4-Day Workshop MATERIALS LIST Acrylic Paint: Please use Open Acrylics so they stay workable throughout class. Golden and Liquitex both make "Open" versions of their paint. If you already have heavy-bodied paint, you may want to contact the manufacturer to ask what medium they would recommend to add to their paint to make it "open". You will need a cool and warm of each primary color. 1. Titanium White (PW 6) 2. Zinc White (PW 4) 3. Pyrrole Red Light (PR 255) 4. Quinacridone Crimson (PR 206 / PR 202) 5. C.P. Cadmium Yellow Primrose (PY 35) 6. Hansa Yellow Medium (PY 73) 7. Yellow Ochre (PY 43) 8. Ultramarine Blue (PB 29) 9. Cerulean Blue (PB 36:1) 10. Burnt Sienna (PBr 7) 11. Burnt Umber (PBr 7) 12. Raw Umber (PBr 7) 13. Dioxazine Purple (PV 23) 14. Prussian Blue (PB15:1 / PV23 / Pbk9) 15. Cadmium Orange (PO 20) (This will likely be the most expensive color and used on most dark skin tones) *Optional - You can purchase SATIN Glazing Medium to extend your paints or use OPEN paints. Water Cup (Glass jar is helpful) Spray bottle (the kind for spraying house plants) Bag of WHITE rags (Southland Hardware - or any other hardware store has these) Art League School – Winter 2018 Oil Paint: *I have included the color index code for each pigment. (Ex: PY34). If you choose to use your favorite brand, please go by the color index code instead of the color name. -

George Washington Carver and the Ancient Egyptian Connection

Professional Agricultural Workers Journal Volume 3 Number 1 Professional Agricultural Workers Article 3 Journal (PAWJ) 9-25-2015 George Washington Carver and the Ancient Egyptian Connection Jon Adkins Elements 4 Nature, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://tuspubs.tuskegee.edu/pawj Part of the African Languages and Societies Commons, Agriculture Commons, Plant Sciences Commons, and the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Adkins, Jon (2015) "George Washington Carver and the Ancient Egyptian Connection," Professional Agricultural Workers Journal: Vol. 3: No. 1, 3. Available at: https://tuspubs.tuskegee.edu/pawj/vol3/iss1/3 This Reflections and Commentaries is brought to you for free and open access by Tuskegee Scholarly Publications. It has been accepted for inclusion in Professional Agricultural Workers Journal by an authorized editor of Tuskegee Scholarly Publications. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GEORGE WASHINGTON CARVER LIVES ON: CHANGING THE WORLD IN UNCOMMON WAYS LECTURE PROFESSIONAL AGRICULTURAL WORKERS CONFERENCE, 2014 GEORGE WASHINGTON CARVER AND THE ANCIENT EGYPTIAN CONNECTION *Jon Adkins1 1Elements 4 Nature, Laurel, MD *Email of author: [email protected] Good morning! My name is Jon Adkins, the founder of Elements 4 Nature. We currently sell some of the original George Washington Carver products that he discovered from the peanut. As you know, Carver produced over 300 products from the peanut while teaching at Tuskegee Institute. Hopefully, before my presentation is over, I will have time to tell you how we are able to sell George Washington Carver original products. In the meantime, I will give you a chance to touch and feel the two most popular original products that Carver created. -

Rare Earth Elements in the Periodic Table ? Why ? 1 18 2 13 14 15 16 17

LECTURE SCHEDULE Date Topic 1. Wed 28.10. Course Introduction & Short Review of the Elements 2. Fri 30.10. Periodic Properties & Periodic Table & Main Group Elements (starts) 3. Fri 06.11. Short Survey of the Chemistry of Main Group Elements (continues) 4. Wed 11.11. Ag, Au, Pt, Pd & Catalysis (Antti Karttunen) 5. Fri 13.11. Redox Chemistry 6. Mon 16.11. Transition Metals: General Aspects & Crystal Field Theory 7. Wed 18.11. Zn, Ti, Zr, Hf & Atomic Layer Deposition (ALD) 8. Fri 20.11. V, Nb, Ta & Metal Complexes and MOFs 9. Mon 23.11. Cr, Mo, W & 2D materials 10 Wed 25.11. Mn, Fe, Co, Ni, Cu & Magnetism and Superconductivity 11. Fri 27.11. Resources of Elements & Rare/Critical Elements & Element Substitutions 12. Mon 30.11. Lanthanoids + Actinoids & Pigments & Luminescence & Upconversion 13. Wed 02.12. Inorganic Materials Chemistry Research EXAM: Thu Dec 10, 9:00-12:00 (IN ZOOM) PRESENTATION TOPICS/SCHEDULE Wed 18.11. Ti: Ahonen & Ivanoff Mon 23.11. Mo: Kittilä & Kattelus Wed 25.11. Mn: Wang & Tran Ru: Mäki & Juopperi Fri 27.11. In: Suortti & Räsänen Te: Kuusivaara & Nasim Mon 30.11. Eu: Morina U: Musikka & Seppänen QUESTIONS: Lecture 12 List all the possible lanthanoid ions that have 7 f electrons. List all the possible lanthanoid ions that have 14 f electrons. Why Eu has so low melting point? Which way you prefer to place the rare earth elements in the periodic table ? Why ? 1 18 2 13 14 15 16 17 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 f-BLOCK TRANSITION METALS - lanthanides [elements after La: Ce Lu] - actinides [elements after Ac: Th Lr] - lanthanoids (Ln): La + Lanthanides - rare earth elements (RE): Ln + Y + Sc ABUNDANCES RARE EARTH ELEMENTS (= METALS) Discovery history starts from and ends in Finland: - Johan Gadolin (prof. -

Ancient Egyptian Colours As a Contemporary Fashion

Journal of the International Colour Association (2012): 9, 32-47 El-Mageed & Ibrahim Ancient Egyptian colours as a contemporary fashion Esmat Abd El-Mageed and Sahar Ahmed Ibrahim Faculty of Applied Arts, University of Helwan, Cairo, Egypt Email: [email protected] There have been numerous terms used by historians to indicate how much Western arts and crafts have been influenced by Ancient Egypt over the years. ‘Egyptomania’ is a term that was first used in France in the 1990s, following on from Western fascination with Pharonic ornamental arts. This study initially analyses the colours of a number of jewellery artworks that were discovered in Tutankhamun’s tomb. From this, a contemporary colour palette based on the Ancient Egyptian has been devised and applied in the design of a summer season’s fashion collection. In all, eight designs have been proposed that mix colour symbolism of Ancient Egyptian arts with its significance at the present time. Received 09 February 2010; revised 28 July 2010; accepted 26 August 2010 Published online: 01 November 2012 Introduction In 1922, a wealth of history was also uncovered with the discovery of the tomb of Tutankhamun, an Egyptian pharaoh of the 18th dynasty (ruled ca. 1333 BC–1323 BC in conventional chronology). This discovery sparked a renewed public interest in Ancient Egypt and exhibits of artifacts from his tomb have toured the world. ‘Egyptomania’ is a term that was first used in the 1990s by Christine Ziegler, the manager of the Egyptian Antiquities Department of the Louvre Museum in France, following on from the Western fascination with Pharonic ornamental arts. -

2Bbb2c8a13987b0491d70b96f7

An Atlas of Rare & Familiar Colour THE HARVARD ART MUSEUMS’ FORBES PIGMENT COLLECTION Yoko Ono “If people want to make war they should make a colour war, and paint each others’ cities up in the night in pinks and greens.” Foreword p.6 Introduction p.12 Red p.28 Orange p.54 Yellow p.70 Green p.86 Blue p.108 Purple p.132 Brown p.150 Black p.162 White p.178 Metallic p.190 Appendix p.204 8 AN ATLAS OF RARE & FAMILIAR COLOUR FOREWORD 9 You can see Harvard University’s Forbes Pigment Collection from far below. It shimmers like an art display in its own right, facing in towards Foreword the glass central courtyard in Renzo Piano’s wonderful 2014 extension to the Harvard Art Museums. The collection seems, somehow, suspended within the sky. From the public galleries it is tantalising, almost intoxicating, to see the glass-fronted cases full of their bright bottles up there in the administra- tive area of the museum. The shelves are arranged mostly by hue; the blues are graded in ombre effect from deepest midnight to the fading in- digo of favourite jeans, with startling, pleasing juxtapositions of turquoise (flasks of lightest green malachite; summer sky-coloured copper carbon- ate and swimming pool verdigris) next to navy, next to something that was once blue and is now simply, chalk. A few feet along, the bright alizarin crimsons slake to brownish brazil wood upon one side, and blush to madder pink the other. This curious chromatic ordering makes the whole collection look like an installation exploring the very nature of painting. -

Philip Ball the Invention of Colour

Philip Ball: The Invention of Colour 1 Philip Ball The Invention of Colour The 2011 Van Gogh exhibition at the Royal Academy in London was widely praised for revising our view of the Dutch artist. Its central focus was a selection of Van Gogh’s correspondence with his brother Theo, and these letters show that he did not work in a crazed frenzy, as the romantic legend might have us believe, but was methodical and thoughtful about his technique. The letters, which are of course long familiar to art historians, reveal a man passionate not so much about love and death as about art, and in particular about its techniques and materials. One great source of inspiration for Van Gogh was colours, especially the new colours that during his lifetime had only recently become available to artists. He wrote to Theo that: I have got new ideas and I have new means of expressing what I want, because better brushes will help me, and I am crazy about those two colours, carmine and cobalt. Cobalt is a divine colour, and there is nothing so beautiful for putting atmosphere around things. Carmine is the red of wine, and it is warm and lively like wine. The same with emerald-green. It is bad economy not to use these colours, the same with cadmium.1 This focus on materials is not unusual among artists. Van Gogh’s friend Paul Gauguin was preoccupied on Tahiti not with metaphysical questions – where we are from, where we are going – nor about his sexual relations with the local women, as again legend might encourage us to believe, but about the very prosaic difficulty of getting the pigments he needed. -

Ancient Egyptian Blue (Cacusi4o10) Pigment by Modern Solution Combustion Synthesis Method

Eurasian Chemico-Technological Journal 18 (2016) 31-37 Ancient Egyptian Blue (CaCuSi4O10) Pigment by Modern Solution Combustion Synthesis Method A. Panagopoulou1,2, K. Karanasios1, G. Xanthopoulou1* 1 2Department of Protection and Conservation of Cultural Heritage, Technological Educational Institute of Ionian Institute of Materials ScienceIslands, “Demokritos” School of Technological National Center Applications, for Scientific Zante Research, Island, Aghia29 100 Paraskevi, Athens, Greece Article info Abstract Received: The Egyptian blue pigment, CaCuSi4O10, has been used in ancient Egypt from 3000 5 May 2015 BC. This pigment consists of CaCuSi4O10 with variable amounts of wollastonite (CaSiO ), high amount of Cu oxides, cuprite (Cu O) or tenorite (CuO). It was Received and revised form: 3 2 18 July 2015 prepared by melting the high percentage of copper in association with lime and desert sand in the Ancient time. In this work Egyptian blue was produced Accepted: by solution combustion synthesis (SCS) in homogeneous aqueous solution of 28 October 2015 composition: cupper and calcium nitrates, sodium silicate and urea. This method permits chemically stable Egyptian blue fast and economic production. The Egyptian blue composition and structure obtained after SCS and calcination were studied by XRD, FTIR and SEM/EDX analysis. Crystallite size and crystal lattice parameters were calculated. An increase in combustion temperature during SHS and calcinations temperature influence Egyptian blue yield and crystallite size, slightly influence parameters of crystal lattice. 1. Introduction centuries. It was a very expensive pigment and used sparingly [3]. Recently, Egyptian blue has The painting appears in all civilizations in hu- been detected on Attica Lekythoi of Classical peri- man history and is an important tool of religious, od, on wall paintings such as Macedonian tombs at ceremonial and aesthetic perceptions. -

Product Catalog Product Catalog Product

KREMER /// PRODUCT CATALOG www.kremerpigments.com PRODUCT CATALOG Table of Contents Pigments 01 TABLE OF Dyes & Vegetable Color CONTENTS Paints 02 Fillers & Building Materials 03 Mediums, Binders & Glues 04 Solvents, Chemicals & Additives 05 Ready-made Colors & Gilding Materials 3 01 Pigments 06 31 02 Dyes & Vegetable Color Paints Linen, Paper 35 03 Fillers & Building Materials & Foils 41 04 Mediums, Binders & Glues 53 05 Solvents, Chemicals & Additives 07 56 06 Ready-made Colors & Gilding Brushes Materials 66 07 Linen, Paper & Foils 08 69 08 Brushes Tools, Packaging & 74 09 Tools, Packaging & Supplies Supplies 10 82 Books & Color Charts 09 85 11 General Information Books & Color Charts 10 General Information 11 For further information and prices please visit us at www.kremerpigments.com 1 Icon-Legend ICON-LEGEND The following Icons are used in the brochure: Hazardous Item Read the Material Safety Data sheet carefully – you can find all Disclaimer product sheets under www.kremerpigments.com and consult our safe handling procedures – see Chapter 11. Not for home use! To buy this product you have to be over 21 years old. Please send us a copy of your identity card . These products require a Hazardous Item Disclaimer. Please fill out the form on page 116 or at www. kremerpigments. com and submit with your order. Cautionary Products may contain hazardous substances. Label Read the ACMI cautionary label carefully and consult our safe handling procedures – see Chapter 11. For further product-specific information please visit us at www.kremerpigments.com. Approved Products bearing the AP Product Seal of ACMI are certified in a Product program of toxicological evaluation By a medical expert to con- tain no materials in suMcient quantities to be toxic or injurious to humans or cause acute or chronic health problems. -

Ancient Warriors and the Origin of Chinese Purple

Science Highlight – March 2007 Ancient Warriors and the Origin of Chinese Purple In March 1974 during the sinking of wells for farmland irrigation near Xi'an, China, 9 farmers made one of the world’s most remarkable archaeological finds: the discovery of an army consisting of more than 8000 life-size terra cotta figures of warriors and horses of the First Emperor of Qin. One of the most intriguing puzzles is the purple synthetic pigments (“Chinese Purple” or “Han Purple” [1]) found on the terra cotta soldiers (figure 1). Until the 19th century, most pigments were based on naturally occurring colored minerals and dyes, with three significant exceptions: Egyptian Blue (CaCuSi2O10), Chinese Blue (BaCuSi2O10)/ Purple Figure 1: (a) Warrior # T18G21-08, a kneeling (BaCuSi2O6) and Maya Blue. The former two are alkaline-earth copper silicates, and because of archer. The pigment samples in this study have this similarity it has been proposed that the been taken from this terracotta warrior. (b) Close-up picture of the purple paint on the Chinese pigments were derived from Egyptian terracotta warrior. (c) Images of the purple paint Blue [2]. samples used in this study. This supposition, however, leaves many open questions. First, it is unlikely that the Chinese chemists could have acquired the technology (not just the pigment) from Egypt well before the official “silk road” (125 BC). Some earliest Chinese Purple samples date back to the “Warring States” period (479-221 BC). Considering the time needed to switch a calcium-based technology to a barium-based one, this technology transfer, if there was one, must have happened well before the “Warring States” period.