The Influence of Lucretius on Dryden

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Unit-22 the Age of Dryden Unit-23 John Dryden Unit-24 Mac Flecknoe Unit-25 Pope: a Background to an Epistle to Dr

This course material is designed and developed by Indira Gandhi National Open University (IGNOU), New Delhi. OSOU has been permitted to use the material. Master of Arts ENGLISH (MAEG) MEG-01 BRITISH POETRY Block – 5 The Neoclassical poets : Dryden and Pope UNIT-22 THE AGE OF DRYDEN UNIT-23 JOHN DRYDEN UNIT-24 MAC FLECKNOE UNIT-25 POPE: A BACKGROUND TO AN EPISTLE TO DR. ARBUTHNOT UNIT-26 POPE: THE STUDY OF AN EPISTLE TO DR. ARBUTHNOT The Neoclassical Poets UNIT 22 THE AGE OF DRYDEN Structure 22.0 Objectives 22.1 Introduction 22.2 The Social Background of Restoration and Early 18thcentury England 22.2.1 The Court 22.2.2 The Theatre 22.2.3 The Coffee House and the Periodicals 22.2.4 Natural Calamities 22.2.5 Social Change 22.2.6 Learning and Education 22.3 The Intellectual Milieu 22.3.1 Science and Scepticism 22.3.2 Science and Poetry in the Augustan Age 22.4 The Literary Context 22.4.1 The Neo-classical Age 22.4.2 Language 22.4.3 Poetic Diction 22.4.4 Poetry-verse-prose-prose Fiction 22.4.5 The Heroic Couplet 22.4.6 Prose and Prose Fiction 22.4. 7 Literary Criticism 22.5 Religion, Philosophy and Morality 22.5.l Religion and Science 22.5.2 Quakerism 22.5.3 Deism 22.5.4 Mysticism, Methodism, Evangelicalism 22.6 Let Us Sum Up 22.7 Questions 22.8 Important Dates 22.9 Suggested Readings 22.0 OBJECTIVES The objective of these units is to introduce you to the age of John Dryden (1631- 1700) the most important man of letters of Restoration England (1660-1700), and Alexander Pope (1688-17 44). -

As Guest, Some Pages Are Restricted

RELIG IONS ' ANCIENT AND MODERN B EDWARD GLODD au h o The Stor o Crea t o i n . Animism . y , t r of y f P B 'AMES ALLANSON PI CTON au h o f The li ion o the anth eism. y , t or Re g f Th li fAn en China . B P s G ILES LL . D . P s e Re g ions o ci t y rofes or , rofe sor f h e iv am d o Ch inese in t U n ersit o f C bri ge. B ' E H R R ISO u at Th e l i n f An i n . L Re ig o o c e t reece y AN A N , ect rer Ne vnha m C ll Camb d a u h o of Prole omm a. t o Stud o Greek v o ege, ri ge, t r g y f Rel igion . h e R H on. AMBER AL I SYED f h ud l m f His I B t t . o t e ' a C m e o slam. y , ici o itt e ’ s C un l au h o of The S it o slam and E hics o Isla m. Maje ty s Privy o ci , t r pir f I t f M i and Fe i hism . B Dr. A. C . H ADDON L u o n ag e t s y , ect rer hnolo a Ca m d e n s gt gy t bri g U iver ity . -

POPES HORATIAN POEMS.Pdf (10.50Mb)

THOMAS E. MARESCA OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY PRESS $5.00 POEMS BY THOMAS E. MARESCA Recent critical studies of Alexander Pope have sought to define his poetic accom plishment in terms of a broadened aware ness of what the eighteenth century called wit. That Pope's achievement can be lo cated in wit is still generally agreed; but it now seems clear that the fullest signifi cance of his poetry can be found in the more serious meaning the Augustans at tached to that word: the ability to discern and articulate—to "invent," in the classical sense—the fundamental order of the world, of society, and of man, and to express that order fittingly in poetry. Mr. Maresca maintains that it is Pope's success in this sort of invention that is the manifest accomplishment of his Imitations of Horace. And Mr. Maresca finds that, for these purposes, the Renaissance vision of Horace served Pope well by providing a concordant mixture of rational knowledge and supernatural revelation, reason and faith in harmonious balance, and by offer ing as well all the advantages of applying ancient rules to modern actions. Within the expansive bounds of such traditions Pope succeeded in building the various yet one universe of great poetry. Thomas E. Maresca is assistant professor of English at the Ohio State University, POPE'S POEMS For his epistles, say they, are weighty and powerful; hut his bodily presence is weak, and his speech contemptible. H COR. io: 10 POPE'S HORATIAN POEMS BY THOMAS E. MARESCA OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY PRESS Copyright © 1966 by the Ohio State University Press All Rights Reserved Library of Congress Catalogue Card Number: 66-23259 MEIS DEBETUR Preface THIS BOOK is an attempt to read some eighteenth-century poems; it is much more a learning experiment on my part than any sort of finished criticism. -

Epicuro Y Su Escuela

EPICURO Y SU ESCUELA MARCELINO RODRÍGUEZ DüNÍS I. SITUACIÓN HISTÓRICA En el período helenístico surgen con gran fuerza tres escuelas de filosofía: la epicúrea, la estoica y la escéptica. Entre ellas hay más coincidencias de lo que en general se cree, aunque, ciertamente, el hilo conductor que las une radica en el afán por asegurar al hombre la serenidad y tranquilidad de ánimo, difíciles de conseguir en un mundo tan sumamente complejo y turbulento como el que sigue a la conquista del Oriente por parte de Alejandro. Sería un error sostener que la filosofía helenística en conjunto ocupa una si tuación secundaria respecto de los grandes sistemas de Platón y Aristóteles, aun que es cierto que el pensamiento espiritualista sufre un duro golpe con los epicúreos y los escépticos. En el estoicismo, por el contrario, hay, a pesar de su materialis mo corporealista, mayor afinidad con el platonismo. Los factores que explican la escasa atención que Epicuro presta a las tesis fundamentales de Platón y Aristóteles son de muy diversa índole. Las circunstancias históricas han cambiado. Alejandro, el discípulo de Aristóteles y el conquistador del mundo conocido, había demostra do que el orgullo y la autocomplacencia de los griegos se basaban al fin y al cabo en un vergonzante provincianismo. Otros mundos más exuberantes se habían abierto ante las mentes atónitas e incrédulas de los nuevos conquistadores, otros dioses, otras costumbres, otros hombres. Ya nada podía ser como antes. Los moldes den tro de los que se había desarrollado la vida de los griegos hasta entonces ya no servían; hasta los mismos dioses de la ciudad habían dejado de existir o estaban alejados de los intereses patrios, sordos a las súplicas de los hombres que, a pesar de rendirles el culto debido, no encontraban en ellos las fuerzas necesarias para seguir ostentando la merecida supremacía personal y colectiva sobre los otros pue blos. -

The Polemical Practice in Ancient Epicureanism* M

UDK 101.1;141.5 Вестник СПбГУ. Философия и конфликтология. 2019. Т. 35. Вып. 3 The polemical practice in ancient Epicureanism* M. M. Shakhnovich St. Petersburg State University, 7–9, Universitetskaya nab., St. Petersburg, 199034, Russian Federation For citation: Shakhnovich M. M. The polemical practice in ancient Epicureanism. Vestnik of Saint Petersburg University. Philosophy and Conflict Studies, 2019, vol. 35, issue 3, pp. 461–471. https://doi.org/10.21638/spbu17.2019.306 The article explores the presentation methods of a philosophical doctrine in Greek and Ro- man Epicureanism; it is shown that for the ancient, middle, and Roman Epicureans a con- troversy with representatives of other philosophical schools was a typical way of present- ing their own views. The polemical practice, in which the basic principles of Epicureanism were expounded through the criticism of other philosophical systems, first of all, Academics and Stoics, was considered not only as the preferred way of presenting the own doctrine, but also as the most convenient rhetorical device, which had, among other things, didac- tic significance. The founder of the school, Epicurus, often included in his texts the terms used in other philosophical schools, giving them a different, often opposite, content. While presenting his teaching in the treatise “On Nature” or in letters to his followers, Epicurus pushed off the opinions of Democritus, Plato, and the Stoics, but resorted mainly to implicit criticism of his opponents, often without naming them by name. His closest students and later followers — Metrodorus, Hermarchus, Colotes, Philodemus, Lucretius, Diogenes of Oenoanda — continuing the controversy with the Academics and the Stoics, more frank- ly expressed their indignation about the “falsely understood Epicureanism” or erroneous opinions. -

Reading of “De Rerum Natura” in the Light of Modern Physics

Open Journal of Philosophy 2012. Vol.2, No.4, 268-271 Published Online November 2012 in SciRes (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/ojpp) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ojpp.2012.24039 Reading of “De Rerum Natura” in the Light of Modern Physics Gualtiero Pisent Istituto Nazionale di Fisica Nucleare, Sezione di Padova, Padova, Italy Email: [email protected] Received April 28th, 2012; revised May 30th, 2012; accepted June 10th, 2012 An analysis of the Lucretius atomism is given, that makes particular reference to the naturalistic argu- ments and contents of the poem. A possible comparison with the atomism of nowadays, based on quite new, both theoretical (quantum mechanics) and experimental (particle accelerators) grounds, must be treated with much care. But it seems possible and interesting to compare at least the world outlined by Lucretius, with the new world, derived by familiarity with modern theories of matter. This is the point I have tried to stress. Keywords: Science; Nature; Atomism; Vacuum; Swerve Introduction gust of wind, which lashes the sea, strikes the ships and drag- sthe clouds [I-265].” Although Lucretius theories are not fully original (being de- We shall see later on, the reasons that suggest the atomistic rived in particular from Epicurus), the poem “De rerum natura” idea, but first of all we must be aware that the assumption, al- is so wide, self consistent and miraculously integral in the form though not trivial, is nevertheless realistic. arrived up to our days, that it is worthwhile to be studied and “The clothes, left on the seaside, become wet. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses Studies in the heroic drama of John Dryden Blyth, Michael Graham How to cite: Blyth, Michael Graham (1978) Studies in the heroic drama of John Dryden, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/8000/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk Studies in the Heroic Drama of John Dryden Thesis submitted to the University of Durham for the degree of Ph.D. by Michael Graham Blyth The copyright of this thesis rests with the author No quotation from it should be published without his prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged 2rsity of Durham Tiber 1978 Acknowledgements My sincere thanks go to the following for their invaluable assistance: Dr. Ray Selden, Durham University English Department, who has given a great deal of his time and critical energy to supervising my work in all stages of its development; Mr. -

The Cambridge Companion to John Dryden - Edited by Steven N

Cambridge University Press 0521824273 - The Cambridge Companion to John Dryden - Edited by Steven N. Zwicker Frontmatter More information The Cambridge Companion to John Dryden John Dryden, Poet Laureate to Charles II and James II, was one of the great literary figures of the late seventeenth century. This Companion provides a fresh look at Dryden’s tactics and triumphs in negotiating the extraordinary political and cultural revolutions of his time. The newly commissioned essays introduce readers to the full range of his work as a poet, as a writer of innovative plays and operas, as a purveyor of contemporary notions of empire, and most of all as a man intimate with the opportunities of aristocratic patronage as well as the emerging market for literary gossip, slander and polemic. Dryden’s works are examined in the context of seventeenth-century politics, publishing and ideas of authorship. A valuable resource for students and scholars, the Companion includes a full chronology of Dryden’s life and works and a detailed guide to further reading. steven n. zwicker is Stanley Elkin Professor of Humanities at Washington University, St. Louis and Professor of English. He is the editor of The Cambridge Companion to English Literature, 1650–1740 (Cambridge, 1998), Reading, Society, and Politics in Early Modern England, ed. with Kevin Sharpe (Cambridge, 2003), John Dryden: Selected Poems (2001), Refiguring Revolu- tions, ed. with Kevin Sharpe (1998), Lines of Authority (1993), Politics of Dis- course, ed. with Kevin Sharpe (1987) and Politics and Language in Dryden’s Poetry (1984). © Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 0521824273 - The Cambridge Companion to John Dryden - Edited by Steven N. -

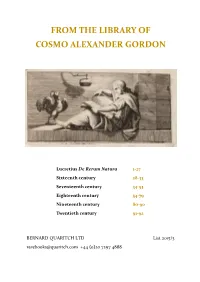

From the Library of Cosmo Alexander Gordon

FROM THE LIBRARY OF COSMO ALEXANDER GORDON Lucretius De Rerum Natura 1-27 Sixteenth century 28-33 Seventeenth century 34-53 Eighteenth century 54-79 Nineteenth century 80-90 Twentieth century 91-92 BERNARD QUARITCH LTD List 2015/3 [email protected] +44 (0)20 7297 4888 Introduction by Nicolas Barker ‘Cosmo and I found our tastes and interests were always in harmony and I came to love his particular sense of humour and gentle goodness, as well as to respect his unusual style of scholarship and general culture.’ So wrote his life-long friend, Geoffrey Keynes in The Gates of Memory. All those who knew him shared the same feeling of calm and contentment, leavened by humour, in his company. Something of this radiates from this residue of a collection of books, never large but put together with a discrimination, a sense of the sum of all the properties of any book, that give it a special quality. Cosmo Alexander Gordon was born on 23 June 1886, the son of Arthur and Caroline Gordon of Ellon, Aberdeen. Ellon Castle was a modest late medieval building, with eighteenth-century additions and yew avenue, the river Ythan running by, where Cosmo fished for salmon and sea-trout. Dr Johnson stayed there in 1773 and admired the local antiquities. So did Cosmo; his taste had extended to medieval manuscripts before he left Rugby for King’s in 1904, where it was nurtured by M. R. James. Although Keynes had also been at Rugby, they did not meet until both were at Cambridge, where Gordon introduced his new friend to David’s book-stall and seventeenth-century literature; they shared a passion for Browne and Fuller. -

The Theory of Pleasure According to Epicurus 4 7

The Theory of Pleasure According to Epicurus 4 7 The Theory of Pleasure According to Epicurus Victor Brochard Translated and edited by Eve Grace Colorado College [email protected] Note: Victor Brochard (1848-1907) was a French scholar whose work was praised very highly by, among others, Friedrich Nietzsche and Leo Strauss. In Ecce Homo, Nietzsche described Brochard’s The Greek Skeptics as a “superb study” (1967, 243). During a course on Cicero given in the spring quarter at the University of Chicago in 1959, Strauss praised Brochard as among the greatest students of Greek philosophy prior to the First World War, and described this article as one of the rare cases in which, in his view, a problem has been properly solved. “La théorie du plaisir d’après Épicure” was first published in Journal des Savants (1904, 156-70, 205-13, 284-90), then reprinted in a collection of Brochard’s articles entitled Études de Philosophie Ancienne et de Philosophie Moderne (Paris: Vrin, 1954). It is here translated into English for the first time and reprinted by kind permission of Librairie Philosophique J. Vrin. I All those who have studied the moral philosophy of Epicu- rus with some care know that while the philosopher defines the sovereign good as pleasure, he gives to this word a very particular meaning which is not that of ordinary speech or of common opinion (Schiller 1902; cf. Guyau 1878; Usener 1887; Natorp 1893).1 But what exactly is this meaning? How did Epicurus conceive of pleasure? Here the difficulty begins. Most historians, perhaps excepting only Guyau, accept that according to Epicurus pleasure © 2009 Interpretation, Inc. -

Eliopoulos Panos. Epicurus and Lucretius on the Creation of The

Eliopoulos Panos . Epicurus and Lucretius on the Creation of the Cosmos РАЗДЕЛIV COSMOLOGYINPERSONS КОСМОЛОГИЯВЛИЦАХ EPICURUS AND LUCRETIUS ON THE CREATION OF THE COSMOS PANOS ELIOPOULOS – Ph.D., University of Peloponnese, (Tripoli, Greece) E-mail:[email protected] Abstract: Although in the extants of Epicurus there is not a direct mention to the atomic swerve, other sources, among them Lucretius, confirm that the Athenian philosopher foresaw in the presence of this unpredictable atomic movement the solution for the cosmological problem. In the epicurean system, as presented through the writings of Epicurus and Lucretius, the creation of the cosmos is owed to the presence of atoms, which form compound bodies, and the void, which allows unimpeded movement. Keywords: Epicurus, Lucretius, Cosmos, Creation, Atom, Atomic Motion, Swerve. ЭПИКУР И ЛУКРЕЦИЙ О СОЗДАНИИ КОСМОСА ПАНОС ЭЛИОПУЛОС – доктор философии, Пелопонесский университет (г. Триполи, Греция) Статья посвящена компаративному анализу космологических концепций древнегрече- ского философа Эпикура и его последователя и доксографа, римского поэта и философа Лукреция. Сделан вывод о том, что и Эпикур, и Лукреций не представляют Вселенную хаосом, полагая, что сотворение и функционирование космоса подчинено законам природы и определенному порядку, наиболее значительная и исключительную роль в котором от- ведена атомам. Ключевые слова: Эпикур, Лукреций, космос, создание, атом, движение атомов. The aim of the epicurean reports on Physics is, according to Epicurus himself, to become acquainted with the celestial phenomena so as not to attribute to them characteristics that are shared only in the lives of men, such as will, deliberate action, or even causality (Epicurus, Letter to Herodotus , 80–82). Knowing science, discover- © EliopoulosPanos, 2015 ISSN 2307-3705. -

Lucretius Carus, Titus

Lucretius Carus, Titus. Addenda et Corrigenda* ADA PALMER (University of Chicago) The Addenda follow the order of the original article (CTC 2.349–65) and consist of a) additional material for the Fortuna, Bibliography and commen- taries, b) vernacular translations of the seventeenth century. New information on copyists, owners and annotators is included within the Fortuna, following the original structure. Fortuna p. 349a4. Add: A theory, now discredited, was much discussed in the fifteenth century that the surviving six-book poem was actually the middle or end of a twenty-one- book work. This confusion arose from a passage in M.T. Varro De( Lingua Latina * The author is grateful for the support and assistance of David Butterfield, Alison Brown, James Hankins and Michael Reeve. She owes much to the support given to her by the Villa I Tatti Harvard University Center for Italian Renaissance Studies, and the Mel- bern G. Glasscock Humanities Center at Texas A&M University. Gracious help was also provided by librarians at many institutions, including the Biblioteca Medicea Lauren- ziana, Biblioteca Nazionale and Biblioteca Berenson, Florence; Biblioteca Nazionale, Rome; Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Vatican City; Biblioteca Marciana, Venice; Biblioteca Ambrosiana, Milan; Biblioteca Comunale A. Mai, Bergamo; Biblioteca Estense, Modena; Biblioteca Malatestiana, Cesena; Biblioteca Comunale Passerini- Landi, Piacenza; Biblioteca Capitolare, Padua; Biblioteca dell’Accademia Rubiconia dei Filopatridi, Savignano sul Rubicone; Biblioteca Nazionale, Naples; Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève and Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris; Öffentliche Bibliothek der Uni- versität, Basel; Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Vienna; Cambridge University Library; Bodleian Library, Oxford; Harvard University’s Widener and Houghton Libraries, Cambridge, Mass.; Cushing Memorial Library & Archives, College Station, Tex.; and especially the British Library, London.