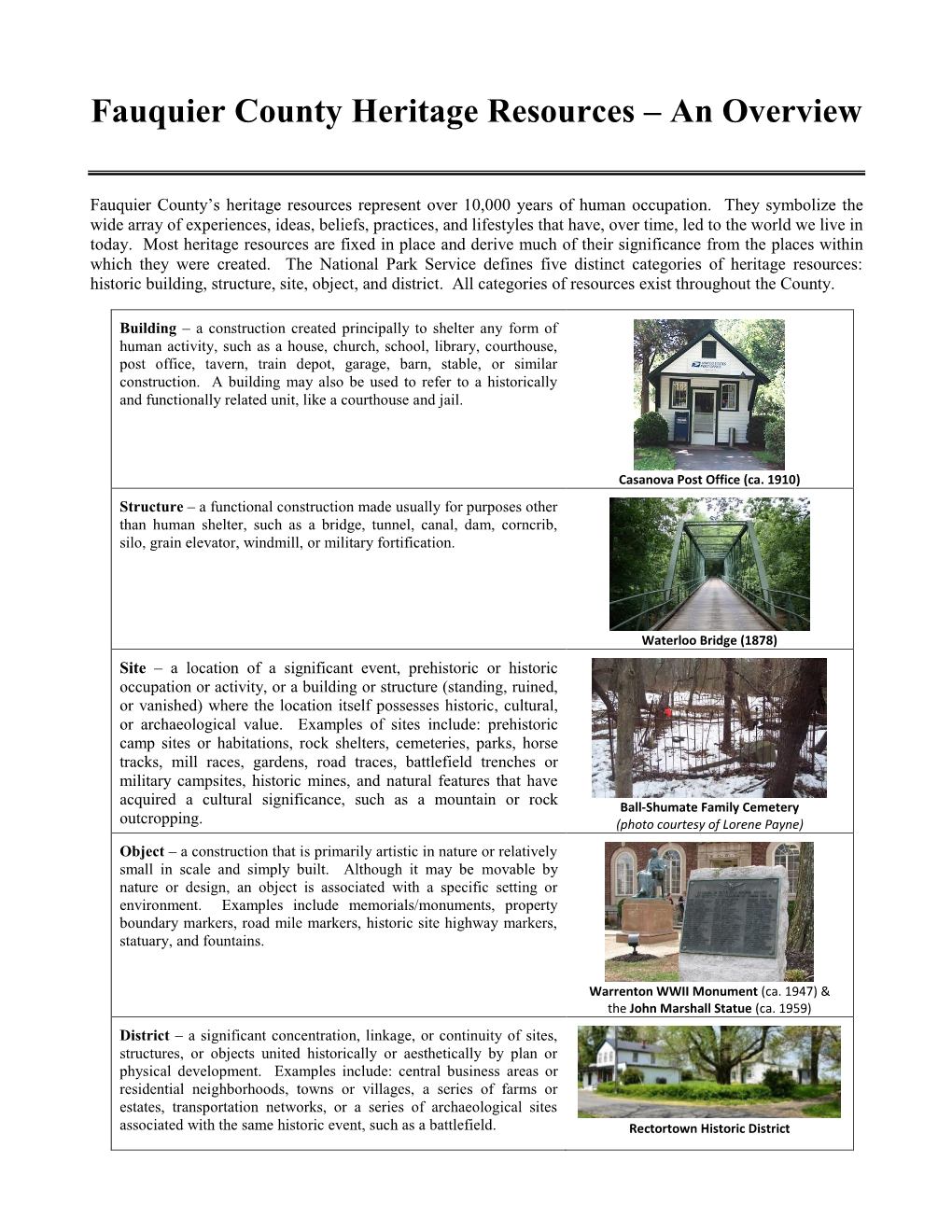

Fauquier County Heritage Resources – an Overview

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

11. Historic Preservation A

Cottonwood General Plan 2025 11. HISTORIC PRESERVATION A. INTRODUCTION Historic preservation is an optimistic and inspiring field of interest intent on improving present and future quality of life awareness through the appreciation of our built and cultural heritage. Historic preservation is architectural history, community planning, historical research and surveys, oral history, archaeology, economic revitalization, and more. It relates directly to quality of life, sense of place and cultural identity. Historic preservation is about preserving, documenting, and incorporating the significant elements of the past into the present and future life of the community. The General Plan’s Historic Preservation Element examines historic preservation issues in the city and establishes goals and objectives intended to help accomplish these goals. Related goals and objectives act as guidelines for property owners, developers, and businesses, as well as City Staff, the Historic Preservation Commission, the Planning and Zoning Commission and City Council when considering historic preservation issues within the city. Preservation of buildings and structures in their original condition with the original intended use can be seen as the ideal expression of historic preservation. However, uses change over time so how a building is used may need to adapt to these changing circumstances to be viable. When there is pressure for change, an analysis of alternative treatments should be considered to determine the appropriate approach to allow alterations without losing the essential historic character of the structure. Repair, reuse or relocation of structures should be considered instead of demolition. Rehabilitation, which includes alterations to a structure, may also be considered where necessary to allow a building use to meet contemporary needs and interests. -

Sun, Sea, Sex, Sand and Conservatism in the Australian Television Soap Opera

This may be the author’s version of a work that was submitted/accepted for publication in the following source: Dee, Mike (1996) Sun, sea, sex, sand and conservatism in the Australian television soap opera. Young People Now, March, pp. 1-5. This file was downloaded from: https://eprints.qut.edu.au/62594/ c Copyright 1996 [please consult the author] This work is covered by copyright. Unless the document is being made available under a Creative Commons Licence, you must assume that re-use is limited to personal use and that permission from the copyright owner must be obtained for all other uses. If the docu- ment is available under a Creative Commons License (or other specified license) then refer to the Licence for details of permitted re-use. It is a condition of access that users recog- nise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. If you believe that this work infringes copyright please provide details by email to [email protected] Notice: Please note that this document may not be the Version of Record (i.e. published version) of the work. Author manuscript versions (as Sub- mitted for peer review or as Accepted for publication after peer review) can be identified by an absence of publisher branding and/or typeset appear- ance. If there is any doubt, please refer to the published source. Author’s final version of article for Young People Now (published March 1996) Sun, Sea, Sex, Sand and Conservatism in the Australian Television Soap Opera In this issue, Mike Dee expands on his earlier piece about soap operas. -

Northern Virginia

NORTHERN VIRGINIA SALAMANDER RESORT & SPA Middleburg WHAT’S NEW American soldiers in the U.S. Army helped create our nation and maintain its freedom, so it’s only fitting that a museum near the U.S. capital should showcase their history. The National Museum of the United States Army, the only museum to cover the entire history of the Army, opened on Veterans Day 2020. Exhibits include hundreds of artifacts, life-sized scenes re- creating historic battles, stories of individual soldiers, a 300-degree theater with sensory elements, and an experiential learning center. Learn and honor. ASK A LOCAL SPITE HOUSE Alexandria “Small downtown charm with all the activities of a larger city: Manassas DID YOU KNOW? is steeped in history and We’ve all wanted to do it – something spiteful that didn’t make sense but, adventure for travelers. DOWNTOWN by golly, it proved a point! In 1830, Alexandria row-house owner John MANASSAS With an active railway Hollensbury built a seven-foot-wide house in an alley next to his home just system, it’s easy for to spite the horse-drawn wagons and loiterers who kept invading the alley. visitors to enjoy the historic area while also One brick wall in the living room even has marks from wagon-wheel hubs. traveling to Washington, D.C., or Richmond The two-story Spite House is only 25 feet deep and 325 square feet, but on an Amtrak train or daily commuter rail.” NORTHERN — Debbie Haight, Historic Manassas, Inc. VIRGINIA delightfully spiteful! INSTAGRAM- HIDDEN GEM PET- WORTHY The menu at Sperryville FRIENDLY You’ll start snapping Trading Company With a name pictures the moment features favorite like Beer Hound you arrive at the breakfast and lunch Brewery, you know classic hunt-country comfort foods: sausage it must be dog exterior of the gravy and biscuits, steak friendly. -

Historic Preservation Commission

HISTORIC PRESERVATION COMMISSION REPORT TO HISTORIC PRESERVATION COMMISSION PREPARED BY: Taylor Long, Associate Planner REVIEWED BY: Mercy Davison, Town Planner DATE: February 9, 2018 SUBJECT: CA-18-01-01: Window Replacement, 603 Normal Ave A. Summary: Replacement of 5 first floor windows at 603 Normal Ave B. Recommended Action: Approval as proposed by applicant C. Background: 1. Property Information: Applicant(s): Tom and Claire Lamonica Owner(s): Tom and Claire Lamonica Location: 603 Normal Ave 2. Property Description: 603 Normal Ave was designated a contributing property to the Old North Normal Historic District by the Town Council in September of 2003 (Ordinance No. 4887). This two-story, side gable Craftsman home was built in 1925 and features a modern rear addition (approved by the HPC in May of 2007) and a detached garage. 1 3. Description of Proposed Alteration: The applicant proposes to install 5 wood, double-hung insert windows externally clad in aluminum in place of 5 original windows on the home. The windows being eyed for replacement are on the north, east, and west facades and are shown circled on the photos above. These original windows are currently covered with aluminum storms, which would be removed as part of this project. The insert windows being proposed have been previously approved by the commission for placement on the home’s modern addition (CA-07-05-09), as replacements for 6 basement windows (CA-12-11-21), and as a suitable replacement for one first-floor window on the south side of the home (CA-17-03-06). The windows proposed by the homeowners and their contractor feature raised, exterior mullions and simulated divided lites. -

Overdeveloped Westchester? Aid in Dying Bill Fails to Pass in Albany

WESTCHESTER’S OLDEST AND MOST RESPECTED NEWSPAPERS Vol 125 Number 26 www.RisingMediaGroup.com Friday, June 24, 2016 Teens Earn Scholarships Look Out, Westchester – To Travel to Israel Project Veritas is Here Yonkers Federation of Teachers President Pat Puleo, on video footage at union offces captured by ProjectVeritas. By Dan Murphy is printed at the end of this story and has been Project Veritas, a website aimed at investi- widely reported on by News 12.) Some of the 20 students heading to Israel this summer, thanks to the UJA-Federation of New gating and exposing corruption across the coun- O’Keefe now has another undercover video York and Singer Scholarship Awards. try, has recently relocated to Westchester, and has that he is about to release featuring another West- Twenty Westchester teens were recently seph Block, Ayelet Marder and Alyssa Schwartz two exposes coming out about the doings – or chester teachers union. The second tape under- awarded Singer Scholarship Awards for summer of White Plains; Joshua Bloom, Doreen Blum, wrongdoings – in the county. scores O’Keefe’s early interest in improper ac- programs in Israel by UJA-Federation of New Sara Butman, Hadas Krasner and Sophia Peister Two weeks ago Project Veritas founder tivities in the county. York. The merit awards, funded by Fran and Saul of New Rochelle; Emily Goldberg of Amawalk; James O’Keefe released an undercover video O’Keefe recently appeared on the blog radio Singer of White Plains, help offset the cost of Is- Sydney Goodman and David Rosenberg of Rye that was taped at the headquarters of the Yon- show for the Yonkers Tribune and explained he rael programs for high school teens. -

Field Trips Guide Book for Photographers Revised 2008 a Publication of the Northern Virginia Alliance of Camera Clubs

Field Trips Guide Book for Photographers Revised 2008 A publication of the Northern Virginia Alliance of Camera Clubs Copyright 2008. All rights reserved. May not be reproduced or copied in any manner whatsoever. 1 Preface This field trips guide book has been written by Dave Carter and Ed Funk of the Northern Virginia Photographic Society, NVPS. Both are experienced and successful field trip organizers. Joseph Miller, NVPS, coordinated the printing and production of this guide book. In our view, field trips can provide an excellent opportunity for camera club members to find new subject matter to photograph, and perhaps even more important, to share with others the love of making pictures. Photography, after all, should be enjoyable. The pleasant experience of an outing together with other photographers in a picturesque setting can be stimulating as well as educational. It is difficullt to consistently arrange successful field trips, particularly if the club's membership is small. We hope this guide book will allow camera club members to become more active and involved in field trip activities. There are four camera clubs that make up the Northern Virginia Alliance of Camera Clubs McLean, Manassas-Warrenton, Northern Virginia and Vienna. All of these clubs are located within 45 minutes or less from each other. It is hoped that each club will be receptive to working together to plan and conduct field trip activities. There is an enormous amount of work to properly arrange and organize many field trips, and we encourage the field trips coordinator at each club to maintain close contact with the coordinators at the other clubs in the Alliance and to invite members of other clubs to join in the field trip. -

Let's Go Camping Guide

Let’s Go Camping Guide compiled by Amangamek-Wipit Lodge 470 Order of the Arrow National Capital Area Council May 2002 To: All NCAC Unit Leaders From: Amangamek-Wipit Camping Committee Subject: LET'S GO CAMPING GUIDE Date: May 2002 Greetings! This is your copy of the annual Let's Go Camping Guide. The National Capital Area Council Order of the Arrow Amangamek-Wipit Lodge updates this guide annually. This guide is intended to support the unit camping program by providing leaders with a directory of nearby campgrounds. The guide is organized into three sections. Section I lists public campgrounds in Delaware, Maryland, Pennsylvania, and Virginia. Section II covers campgrounds administered by the Boy Scouts of America in Maryland, North Carolina, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, Virginia, and West Virginia. Section III provides a place for leaders to record their favorite campgrounds for future reference. Many people have provided listings to this year's edition of the guide and we are grateful to all who have contributed. However, this guide is far from a complete listing of the camping resources available to NCAC units. If you would like to add a listing or if you discover a listing in need of correction please contact Philip Caridi at your convenience at [email protected]. Together we can make next year's guide even more useful. Yours in Scouting and Cheerful Service, Chuck Reynolds Lodge Chief Section I: Public Sites Section II: Boys Scouts of America Campgrounds Section III: Personal Favorites Section IV: Baloo Sites Section I: Public Campgrounds National Capital Area Council Let's Go Camping Guide Order of the Arrow May 2002 Amangamek-Wipit, Lodge 470 ST Camp Season Type Capacity Restricts Fires Toilets/Showers Activities/Features Reservations Directions DE Assawoman Wildlife Area flies/mosquitos 20 Take I 495 to Rte 50; 50 E to very bad in late Ocean City; take Rte 1 N to spring, summer, Fenwick Island; DE Rte 54 W early fall year to county Road 381; turn right and follow signs. -

Recreation Component Plan for Clarke County, Virginia

Recreation Component Plan For Clarke County, Virginia An Implementing Component of the 2013 Comprehensive Plan Adopted by the Board of Supervisors on August 18, 2015 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS CLARKE COUNTY PLANNING COMMISSION George L. Ohrstrom, II, Chair (Russell Election District) Anne Caldwell, Vice Chair (Millwood Election District) Frank Lee (Berryville Election District) Gwendolyn C. Malone (Berryville Election District) Scott Kreider (Buckmarsh Election District) Douglas Kruhm (Buckmarsh Election District) Jon Turkel (Millwood Election District) Cliff Nelson (Russell Election District) Robina Bouffault (White Post Election District) Randy Buckley (White Post Election District) John Staelin (Board of Supervisors representative) CLARKE COUNTY BOARD OF SUPERVISORS David Weiss, Chair (Buckmarsh Election District) Beverly B. McKay, Vice Chair (White Post Election District) J. Michael Hobert, Chair (Berryville Election District) John Staelin (Millwood Election District) Barbara Byrd (Russell Election District) RECREATION PLAN SUBCOMMITEE Daniel Sheetz, Chair Parks and Recreation Advisory Board Lee Sheaffer, Potomac Appalachian Trail Club Pete Engel, Conservation Easement Authority Tom McFillen, Citizen Jon Turkel, Planning Commission Lisa Cooke, Director, Clarke County Parks & Recreation Christy Dunkle, Town of Berryville Staff CLARKE COUNTY PLANNING DEPARTMENT Brandon Stidham, Planning Director Ryan Fincham, Zoning Administrator Alison Teetor, Natural Resource Planner Debbie Bean, Administrative Assistant Clarke County Planning Department 101 -

Of Peotone Township Will County, Illinois

Rural Historic Structural Survey of Peotone Township Will County, Illinois Rural Historic Structural Survey of Peotone Township Will County, Illinois October 2014 for Will County Land Use Department and Will County Historic Preservation Commission Wiss, Janney, Elstner Associates, Inc. Wiss, Janney, Elstner Associates, Inc. 330 Pfingsten Road Northbrook, Illinois 60062 (847) 272-7400 www.wje.com Wiss, Janney, Elstner Associates, Inc. Rural Historic Structural Survey Peotone Township Will County, Illinois TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary vii Federal Assistance Acknowledgement viii Chapter 1 – Background and Methodology Background 1 Survey Methodology 1 Survey Gaps and Future Research 2 Chapter 2 – Context History of the Rural Survey Area Geologic and Topographic Background to the Illinois Region 5 First Nations in the Illinois Region 6 The Arrival of European Settlers 8 Settlement and Development of Northeast Illinois 13 Peotone Township Developmental History 21 Andres 30 Schools 32 Churches 36 Cemeteries 40 Will County Fairgrounds 41 Chapter 3 – American Rural Architecture Farmstead Planning 51 Development of Balloon Framing 51 Masonry Construction 55 Classification of Farmhouses 60 Development of the Barn 73 Barn Types 77 Chapter 4 – Survey Summary and Recommendations Period of Significance 95 Significance 96 Potential Historic Districts, Thematic Designations, and Landmarks 100 Survey Summary 102 Table 1. Surveyed Farmsteads and Related Sites in Peotone Township Table 2. Farmhouses in Peotone Township Table 3. Barns in Peotone Township -

Cultural Resource Surveys

Guidelines For Conducting Cultural Resource Surveys Table of Contents When the NRCS is conducting cultural resource surveys or archaeological field inventories this guidebook will give you a general step by step process to help in completing your field inventory. Prior to field work: Define the project area. 1 Request an ARMS records check. 2 Survey Design: Where are we surveying. 3 What are we looking for? 4 How are we going to survey the project area. 5 In the field survey: What are we going to need to take into the field. 9 Getting started. 10 Findings. 14 Site Boundaries 17 Sketch Maps 18 Writing a site description 21 Appendix A: New Mexico Standards for Survey and Inventory. 22 Appendix B: Example Laboratory of Anthropology Site Record. 39 Archaeological field survey is the methodological process by which archaeologists collect information about the location, distribution and organization of past human cultures across a large area. Why we care. Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act (NHPA). The head of any Federal agency having direct or indirect jurisdiction over a proposed Federal or federally assisted undertaking in any State and the head of any Federal department of independent agency having authority to license any undertaking shall, prior to the approval of the expenditure of any Federal funds on the undertaking or prior to the issuance of any license, as the case may be, take into account the effect of the undertaking on any district, site, building, structure or object that is included in or eligible for inclusion in the National Register. -

An Architectural and Historical Analysis of the Caretaker's House at the Winneshiek County Poor Farm, Decorah Township, Winneshiek County, Iowa

AN ARCHITECTURAL AND HISTORICAL ANALYSIS OF THE CARETAKER’S HOUSE AT THE WINNESHIEK COUNTY POOR FARM, DECORAH TOWNSHIP, WINNESHIEK COUNTY, IOWA Section 14, T98N, R8W Special Report 1 Prepared for Winneshiek County Historic Preservation Commission Courthouse Annex 204 West Broadway Decorah, Iowa 52101 Prepared by Branden K. Scott With contributions by Lloyd Bolz, Derek V. Lee, and David G. Stanley Bear Creek Archeology, Inc. P.O. Box 347 Cresco, Iowa 52136 David G. Stanley, Director February 2012 MANAGEMENT SUMMARY This report presents the findings of an investigation concerning the Winneshiek County Poor Farm (96-00658), and more specifically the Caretaker’s House (96-00644) within the county farm district. This investigation was prepared for the Winneshiek County Historic Preservation Commission because the Caretaker’s House, a structure potentially eligible for the National Register of Historic Places under Criterion A is to be dismantled. This investigation seeks to document the architectural aspects of the property with emphasis on the Caretaker’s House, create a historical and cultural context of the farm, determine the potential significance of the property and each of its contributing/non- contributing features, and provide data necessary for future considerations of the property. This document was prepared by Bear Creek Archeology, Inc. of Cresco, Iowa, and any opinions expressed herein represent the views of the primary author. This report documents the Winneshiek County Poor Farm (96-00658) as a historic district containing three distinct buildings and three associated structures. The district consists of the newly constructed (relatively speaking) Wellington Place care facility (96-00660), the Winneshiek County Poor House (96-00659), the Caretaker’s House (96-00644), two sheds, and a picnic shelter, all of which are settled upon 2.7 ha (6.6 ac) on the west side of Freeport, Iowa. -

Pennsylvania Avenue Cultural Landscape Inventory

National Park Service Cultural Landscapes Inventory Pennsylvania Avenue, NW-White House to the Capitol National Mall and Memorial Parks-L’Enfant Plan Reservations May 10, 2016 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW-White House to the Capitol National Mall and Memorial Parks-L’Enfant Plan Reservations Table of Contents Inventory Unit Summary & Site Plan ............................................................................................ Page 3 Concurrence Status ...................................................................................................................... Page 10 Geographic Information & Location Map ................................................................................... Page 11 Management Information ............................................................................................................. Page 12 National Register Information ..................................................................................................... Page 13 Chronology & Physical History ................................................................................................... Page 24 Analysis & Evaluation of Integrity .............................................................................................. Page 67 Condition Assessment .................................................................................................................. Page 92 Treatment ....................................................................................................................................