NEWSLETTER Winter 2020/21 P.O

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Hyperactive 2020 Hurricane Season

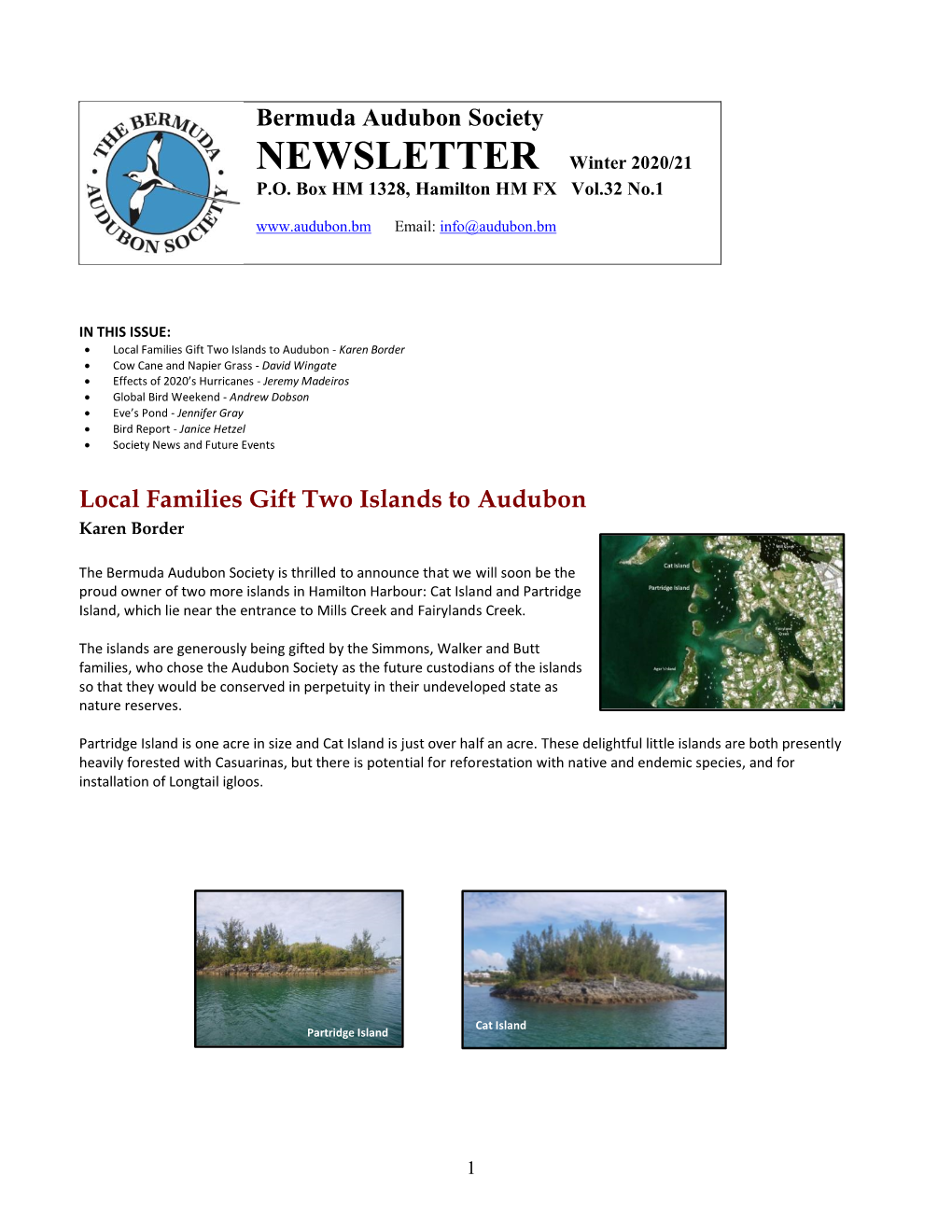

SHORELINES – January 2021 As presented to the Island Review magazine A Hyperactive 2020 Hurricane Season The 2020 Hurricane Season (Figure 1) made history on three noticeable accounts – (1) for the most cyclones (tropical storms and hurricanes) recorded for a single season at 30, (2) for the most cyclones in any month (10 in September), and (3) for the most U.S. Landfalling cyclones in a season at 12. Our closest “near miss” here along the Crystal Coast came when hurricane Isaias made landfall as a Category 1 hurricane south of Cape Fear in Brunswick County during the waning hours of August 3rd. And by virtue of doing so, became the earliest fifth named cyclone to make landfall in the U.S. (another record). In some regards this level of activity was expected – an above average forecast was predicted based predominantly upon the premise that sea surface temperatures were expected to be warmer-than-normal in the Main Development Region (MDR) of the Atlantic and weak tradewinds were also expected in the eastern part of the MDR. Hence the fuel (warm water) was in place for cyclones to develop and little shear was aloft to stymie any cyclones that did begin to form. Also, weak La Niña or “El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO) cool phase” conditions were predicted to be present during the peak of hurricane season, which also can favor, rather than suppress cyclone development. Figure 1 – Graphic prepared by the National Weather Service (NOAA) depicting cyclone tracks and intensities reported for the 2020 hurricane season. - 1 - In reality La Niña conditions were stronger than anticipated and this phenomenon coupled with the warm waters and lack of shear described above proved to be a recipe for a “hyperactive” season as we will detail below, and was notable for a high degree of late season activity in the months of October and November. -

HURRICANE TEDDY (AL202020) 12–23 September 2020

r d NATIONAL HURRICANE CENTER TROPICAL CYCLONE REPORT HURRICANE TEDDY (AL202020) 12–23 September 2020 Eric S. Blake National Hurricane Center 28 April 2021 NASA TERRA MODIS VISIBLE SATELLITE IMAGE OF HURRICANE TEDDY AT 1520 UTC 22 SEPTEMBER 2020. Teddy was a classic, long-lived Cape Verde category 4 hurricane on the Saffir- Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale. It passed northeast of the Leeward Islands and became extremely large over the central Atlantic, eventually making landfall in Nova Scotia as a 55-kt extratropical cyclone. There were 3 direct deaths in the United States due to rip currents. Hurricane Teddy 2 Hurricane Teddy 12–23 SEPTEMBER 2020 SYNOPTIC HISTORY Teddy originated from a strong tropical wave that moved off the west coast of Africa on 10 September, accompanied by a large area of deep convection. The wave was experiencing moderate northeasterly shear, but a broad area of low pressure and banding features still formed on 11 September a few hundred n mi southwest of the Cabo Verde Islands. Convection decreased late that day, as typically happens in the evening diurnal minimum period, but increased early on 12 September. This convection led to the development of a well-defined surface center, confirmed by scatterometer data, and the formation of a tropical depression near 0600 UTC 12 September about 500 n mi southwest of the Cabo Verde Islands. The “best track” chart of the tropical cyclone’s path is given in Fig. 1, with the wind and pressure histories shown in Figs. 2 and 3, respectively. The best track positions and intensities are listed in Table 1.1 After the depression formed, further development was slow during the next couple of days due to a combination of northeasterly shear, dry air in the mid-levels and the large size and radius of maximum winds of the system. -

Storm Watcher Pdf, Epub, Ebook

STORM WATCHER PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Maria V Snyder | 228 pages | 05 May 2013 | Leap Books, LLC | 9781616030339 | English | Powell, WY, United States National Hurricane Center Tropical Storm Wilfred forms over the eastern Atlantic. Tropical Depression 22 forms in the Gulf of Mexico. September 17, September 14, Hurricane Teddy forms over the central Atlantic. September 16, Hurricane Sally has formed over the Gulf of Mexico. September 12, Paulette is now a hurricane over the northwestern Atlantic. September 13, The NHC indicates that Nana has become a hurricane and is expected to make landfall along the coast of Belize tonight. September 02, Tropical Storm Omar forms off the east coast of the United States. September 01, Marco has become a hurricane and could make landfall near the Louisiana coast on Monday. August 23, Tropical Storm Laura becomes a hurricane , forecast to reach category 3 before making landfall on the south coast of the USA. August 25, Tropical Storm Kyle has formed off the east coast of the United States. August 14, August 13, Tropical Depression 10 forms over the eastern Atlantic. J uly 31, Hurricane Isaias moving closer towards southern Florida. August 01, Hanna strengthens and has become the first hurricane of the Atlantic season. July 25, J uly 22, Tropical Storm Fay has formed near the coast of North Carolina. July 09, July 05, Tropical Storm Dolly forms over the north Atlantic. June 23, June 2, Tropical Storm Bertha has formed near the coast of South Carolina this morning. May 27, May 16, Storm Names for the Atlantic Hurricane Season. Tropical Storm Arthur. -

Hurricane Teddy

eVENT Hurricane Tracking Advisory Hurricane Teddy Information from NHC Advisory 40A, 8:00 AM AST Tue Sep 22, 2020 On the forecast track, the center will move over eastern Nova Scotia on Wednesday, and then near or over Newfoundland by Wednesday night. Maximum sustained winds are near 105 mph (165 km/h) with higher gusts. Although some weakening is likely later today and Wednesday, Teddy should be a strong post-tropical cyclone when it moves near and over Nova Scotia. Intensity Measures Position & Heading U.S. Landfall (NHC) Max Sustained Wind 105 mph Position Relative to 365 mi S of Halifax Nova Scotia Speed: (category 2) Land: Est. Time & Region: n/a Min Central Pressure: 950 mb Coordinates: 39.3 N, 63.5 W Trop. Storm Force Est. Max Sustained 400 miles Bearing/Speed: NNW or 335 degrees at 28 mph n/a Winds Extent: Wind Speed: Forecast Summary ■ Tropical storm conditions are expected to begin in the warning area by this afternoon. Tropical storm conditions could begin in the watch areas late today or early Wednesday. ■ Large swells generated by Teddy are affecting Bermuda, the Lesser Antilles, the Greater Antilles, the Bahamas, the east coast of the United States, and Atlantic Canada. These swells are likely to cause life-threatening surf and rip current conditions. A dangerous storm surge is expected to produce significant coastal flooding near and to the east of where the center makes landfall in Nova Scotia. Near the coast, the surge will be accompanied by very large and destructive waves. ■ Through Thursday, Teddy is expected to produce rainfall accumulations of 2 to 4 inches (50 to 100 mm) with isolated totals of 6 inches (150 mm) across sections of Atlantic Canada. -

Alongshore Coupling of Eco-Geomorphological Variables in a Beach-Dune System

University of Windsor Scholarship at UWindsor Electronic Theses and Dissertations Theses, Dissertations, and Major Papers 3-10-2021 Alongshore coupling of eco-geomorphological variables in a beach-dune system Brianna Lunardi University of Windsor Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/etd Recommended Citation Lunardi, Brianna, "Alongshore coupling of eco-geomorphological variables in a beach-dune system" (2021). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 8565. https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/etd/8565 This online database contains the full-text of PhD dissertations and Masters’ theses of University of Windsor students from 1954 forward. These documents are made available for personal study and research purposes only, in accordance with the Canadian Copyright Act and the Creative Commons license—CC BY-NC-ND (Attribution, Non-Commercial, No Derivative Works). Under this license, works must always be attributed to the copyright holder (original author), cannot be used for any commercial purposes, and may not be altered. Any other use would require the permission of the copyright holder. Students may inquire about withdrawing their dissertation and/or thesis from this database. For additional inquiries, please contact the repository administrator via email ([email protected]) or by telephone at 519-253-3000ext. 3208. Alongshore coupling of eco-geomorphological variables in a beach-dune system By Brianna Lunardi A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies through the School of the Environment in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science at the University of Windsor Windsor, Ontario, Canada @2021 Brianna Lunardi Alongshore coupling of eco-geomorphological variables in a beach-dune system By Brianna Lunardi APPROVED BY: S. -

Division 1 Contacts113 Airport Drive Suite 100 Edenton, N.C

DIVISION 1 2019 NCDOTANNUAL Highway REPORT Division 1 | Division 1 Contacts113 Airport Drive Suite 100 Edenton, N.C. 27932 252-482-1850 Division 1 2021 Guide Alleghany Gra C Northampton urr Ashe Vanc Camde n i Person Gates tuck Surry ville Stokes Rockingham Pasquota Caswell Warren e n Hertford Perqui Chowan Watauga Halifax Wilkes Yadkin man nk M Forsyth DIVISION Durha Al s itchell Avery O range a Guilford mance Franklin Yancey Caldwell Davie m Nash 1 Bertie Madison Alexander Iredell Edgecombe n Davidson Martin Tyrrell Burke Dare Randolph Chatham Wake Washingto Haywood Rowan Wilson Buncombe McDowell Catawba Swain Pitt Beaufort Hyde Lincoln Johnston Graham Rutherford Mecklenburg Lee Greene Henderson Cabarrus Stanly Cleveland Harnett Wayne Jackson Polk Gaston Montgomer Moore Cherokee Macon y Lenoir Craven Clay Transylvania Cumberland Pamlico Richmond Hoke Sampson Jones Anson Union d Duplin Carteret Scotlan Onslow Robeson Bladen Pender DIVISION 1 2020 GUIDE | 3 Columbus New Hanover Brunswick NCDOT Highway Division 1 Sterling Baker, PE Allen Moran 113 Airport Drive Division Engineer Board of Transportation Member Suite 100 252-482-1850 252-423-1309 Edenton, N.C. 27932 [email protected] [email protected] 252-482-1850 DIVISION EMPLOYEES 397 1 398 As of July 2020 Permanent Temporary Total DIVISION 1 COUNTIES BERTIE HYDE CAMDEN MARTIN CHOWAN NORTHAMPTON CURRITUCK PASQUOTANK DARE PERQUIMANS GATES TYRRELL HERTFORD WASHINGTON ROAD MILES FERRY ROUTES 5,209 Cedar Island-Ocracoke Currituck-Knotts Island Hatteras-Ocracoke LANE MILES Ocracoke Express -

2021 Pre-Season Brief

Hurricane Preparedness Week 2021 31 May - 4 June 2021 In collaboration with the Government of Bermuda Disaster Risk Reduction Mitigation Team Tropical Cyclone Terminology Tropical Depression Arthur • Tropical Depression* - A tropical cyclone in which the maximum sustained surface wind speed is <34 knots. • Tropical Storm*- A tropical cyclone in which the maximum NASA sustained surface wind speed ranges from 34 to 63 knots. *Also includes Subtropical Cyclones • Hurricane - A tropical cyclone in which the maximum sustained surface wind is 64 knots or higher. • Major Hurricane - A hurricane that is classified as Category 3 or higher, 96 knots and higher BWS Historical Tropical Cyclone Record For Bermuda September and October are the most active months for Bermuda storms Satellite image – Hurricane Fabian, 2003 Notable recent storms: 18 September 2019 Major Hurricane Humberto 12-13 October 2016 Major Hurricane Nicole 17 October 2014 Major Hurricane Gonzalo Storms within 100nm (i.e. meeting BWS Threat criterion) 5 September 2003 Sources: NOAA, BWS, BIOS, University of Reading Major Hurricane Fabian Teddy surge aftermath 2020 Hurricane Season – Impacts • Arthur, Edouard, Paulette, Teddy, & Epsilon threatened Bermuda. • No injuries or fatalities reported through the season. • Hurricane Paulette: • Direct hit, with eye passage right over the island, 6AM ADT Monday 14 Sept 2020. Radar Reflectivity • 25,000 electricity outages (~70% of total) • Estimated >US$50mill in damage. • Hurricane Teddy: • Distant passage, but a surge & wave event Wind Gusts rainfall Surge Waves Storm Site Elev. Spd(kts) (kts) (mm) (m) (m) Pearl Paulette Island 8m ASL 69 82 74 0.73 9 to 10 The Teddy Crescent 6m ASL 53 71 36 0.89 7 to 8 Hurr. -

October 2020

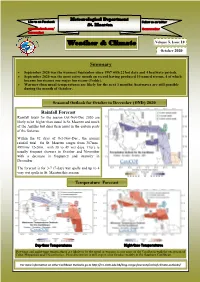

Meteorological Department Like us on Facebook: Follow us on twitter: St. Maarten www.facebook.com/ @sxmweather sxmweather Weather & Climate Volume 5, Issue 10 October 2020 Summary September 2020 was the warmest September since 1987 with 22 hot days and 4 heatwave periods. September 2020 was the most active month on record having produced 10 named storms, 4 of which became hurricanes one major hurricane (Teddy). Warmer than usual temperatures are likely for the next 3 months; heatwaves are still possible during the month of October. Seasonal Outlook for October to December (OND) 2020 Rainfall Forecast Rainfall totals for the season Oct-Nov-Dec 2020 are likely to be higher than usual in St. Maarten and much of the Antilles but drier than usual in the eastern parts of the Guianas. Within the 92 days of Oct-Nov-Dec., the normal rainfall total for St. Maarten ranges from 307mm– 499mm/ 12-20in. with 38 to 49 wet days. There is usually frequent showers in October and November with a decrease in frequency and intensity in December. The forecast is for 3-7 (7-day) wet spells and up to 4 very wet spells in St. Maarten this season. Temperature Forecast Day-time Temperatures Night-time Temperatures Day-time and night-time temperatures are likely to be the usual or warmer across most of the Caribbean with the exception of Cuba, Hispaniola and US territories. Heat discomfort is still expected in October mainly in the Southern Caribbean. For more information on other Caribbean Outlooks go to http://rcc.cimh.edu.bb/long-range-forecasts/caricof-climate-outlooks/ Page 2 WHAT INFLUENCES THIS SEASON’S CLIMATE? In mid September, Sea surface temperatures (SST) in the east-central Pacific were below average and Atmospheric variables were consistent with La Nina conditions. -

Download Press Release

FEMA Response Update: Hurricane Teddy, Tropical Storm Beta, Hurricane Sally and Western Wildfires Release Date: September 22, 2020 WASHINGTON - FEMA continues to support our federal, state, local, tribal and territorial partners by mobilizing teams and supplies to support a state-managed, locally executed response to Tropical Storm Beta in the Gulf of Mexico, impacts from Hurricane Teddy as it moves north along the East Coast, response efforts to Hurricane Sally in the Gulf Coast and the wildfires in the West. Tropical Storm Beta made landfall last night just north of Port O’Connor, Texas, and is expected to stall inland today then begin to move slowly along the coast of Texas through Wednesday with expected isolated storm totals up to 20 inches. Meanwhile, Hurricane Teddy is centered off the northeastern U.S. coast, and is expected to transition to a powerful post-tropical cyclone as it moves near or over portions of Atlantic Canada late today through Thursday. FEMA urges anyone in the forecast path of the storms to monitor their local news for updates and directions provided by their local officials and heed local evacuation orders. Tropical Storm Beta is forecast to bring additional rainfall of 6 to 12 inches with isolated storm totals up to 20 inches expected. Significant flash and urban flooding is occurring and will continue today, we urge everyone to stay focused on safety and encourage to practice the following: Do not return until local officials tell you it is safe to do so. If you have been ordered to shelter in place, please do so until advised it is safe. -

Winter Preview 2020-21

National Weather Service, Newport/Morehead City, NC http://weather.gov/Newport —> Bookmark it!! Winter 2020-21 Edition Winter Preview 2020 -21 By Chris Collins, Meteorologist Despite our location near the ocean and away from the mountains, eastern North Carolina frequently has bouts of severe winter weather and cold. It is actually quite unusual to not have at least some snow or ice during the course of a winter in our area. Annual snowfall typically ranges from 2 inches or less near the coast, with areas around Greenville nor- mally receiving between 4 and 6 inches. Larger storms do occasionally occur. Right be- fore Christmas in 1989, a snowstorm dumped 12 to 18 inches along the coast of eastern North Carolina. These type of winter events produce very hazardous conditions. Before a winter storm, make sure your home, office and vehicles have the supplies you need. Roads often be- come very treacherous and secondary roads are often untreated immediately after a storm. Always carefully plan your travel and check the latest weather reports. CONTENTS Winter Preview 2020- 1 2021 NWS Newport/Morehead 2-3 City now on Instagram Winter Preparedness 4-7 Winter Weather Skywarn 8 New Weather Story Info- 9 graphic Utilizing Dual-Pol Radar for 10- Winter Weather Forecasting 12 Winter Events of 2019- 13- 2020 15 Summary of the Busy 2020 16- Atlantic Hurricane Season 18 Snow in Greene County, February 20-21, 2020 2 NWS Begins Prototype Instagram Social Media Service By Mike Lee, Meteorologist You can now follow us on Instagram! As of November 2 nd , the National Weather Ser- vice launched its Prototype Instagram Social Media Service to determine the potential use of Instagram as a strategic asset for the NWS mission at field offices around the country. -

Forecast for the 2021 Gulf and Atlantic Menhaden Purse-Seine Fisheries and Review of the 2020 Fishing Season March 2021

Forecast for the 2021 Gulf and Atlantic Menhaden Purse-Seine Fisheries and Review of the 2020 Fishing Season March 2021 Southeast Fisheries Science Center, NOAA Beaufort Lab, NC GULF MENHADEN FISHERY INTRODUCTION Gulf Menhaden Landings, Fishing The 2021 fishing year marks the forty-ninth year Conditions, and Vessel Participation in 2020 that the National Marine Fisheries Service has made quantitative forecasts of purse-seine landings of Final purse-seine landings of Gulf Menhaden for menhaden. The forecasts are based on a multiple reduction in 2020 totaled 413,855 metric tons (mt; regression equation that relates landings and 1,361 million standard fish). This is a decrease of fishing effort over the series of years. Landings 15.0% from total landings in 2019 (486,980 mt), forecasts are conditioned on estimates of expected and 17.0% less than the previous 5-year mean fishing effort for the upcoming fishing year. Fishing (498,974 mt; Figure 1). effort estimates are vessel-specific and are derived from 1) industry input regarding the number of Gulf menhaden landings (1,000 metric tons) vessels that companies expect to be active during Nominal fishing effort (1,000 vessel-ton-weeks) the upcoming fishing year, and 2) historical 1,200 700 performance (catch and effort) of the vessels 600 expected to participate in the fishery. In the Atlantic 1,000 Menhaden fishery, actual purse-seine landings have 500 800 Weeks differed an average of 13% from those forecasted - 400 for the forty year period, 1973-2012 (pre-TAC Ton 600 - years; see page 4). Landings in the Gulf Menhaden 300 fishery have differed from those forecasted by an 400 200 average of 13% for the forty-eight year period, 1,000 MetricTons 1973-2020. -

CDRP HRA Atmospheric (Pdf)

Hazard Risk Analysis Atmospheric (related to weather and climate) Blizzards Climate Change Droughts Extreme Cold Fog Frost Hailstorms Heat Waves Hurricanes Ice Fogs, Ice Storms, and Freezing Rain Lake-Effect Storms Lightning and Thunderstorms Microbursts Sea Storms and Sea Surges Seiches Snowstorms Tornadoes and Waterspouts Windstorms Atmospheric Hazards This section introduces a number of atmospheric hazards: Blizzards, Climate Change, Droughts, Extreme Cold, Fog, Frost, Hailstorms, Heat Waves, Hurricanes, Ice Fogs, Ice Storms and Freezing Rain, Lake Effect Storms, Lightning and Thunderstorms, Microbursts (strong wind caused by downdraft), Sea Storms and Storm Surges, Seiche (atmospheric disturbance over water), Snowstorms, Tornadoes and Waterspouts, and Windstorms. As you will see when completing the risk analysis, all are caused by nature but a few are also caused by people (human-caused). The following hazards are weather related. Don’t confuse your community’s ability to cope with the hazard (e.g., a blizzard) with the likelihood of it occurring. For example, you may experience blizzards regularly and thus cope very well – but that doesn’t change the fact that blizzards are very likely to occur. www.cdrp.jibc.ca CDRP: Hazard Risk Analysis Blizzards - Natural Definition Although blizzard is often used to describe any major snow storm with strong winds, a true blizzard lasts at least 3 hours in duration; has low temperatures (usually less than minus 7°Celsius or 20F); strong winds (greater than 55 km/h or 35 mph); and blowing snow which reduces visibility to less that 1 kilometre (0.6 miles). Snow does not need to be falling as long as the amount of snow in the air (falling or blowing) reduces visibility to less than 400m(0.2miles).