Ginkgo, Apricot, and Almond: Change of Chinese Words and Meanings from the Kernel’S Perspective Roland Kirschner and Shelley Ching-Yu Hsieh

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Phosphatidylserine

Cognitive Vitality Reports® are reports written by neuroscientists at the Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation (ADDF). These scientific reports include analysis of drugs, drugs-in- development, drug targets, supplements, nutraceuticals, food/drink, non-pharmacologic interventions, and risk factors. Neuroscientists evaluate the potential benefit (or harm) for brain health, as well as for age-related health concerns that can affect brain health (e.g., cardiovascular diseases, cancers, diabetes/metabolic syndrome). In addition, these reports include evaluation of safety data, from clinical trials if available, and from preclinical models. Phosphatidylserine Evidence Summary May promote cognitive function and protect from decline, especially for DHA-enriched phosphatidylserine. It has a good safety profile but has limited bioavailability. Neuroprotective Benefit: Mixed evidence from clinical trials, and considerable bias in results reporting. Has poor bioavailability and it’s unclear how well it gets into the brain. Aging and related health concerns: No clear rationale or data. One study reported a minor increase in mobility in elderly, but effect can’t be clearly tied to phosphatidylserine. Safety: Well-tolerated with no serious adverse events reported in short trials. May slightly reduce blood pressure. Information on long-term safety is not available. 1 What are they? Phosphatidylserine (PS) is a class of phospholipids that help to make up the plasma membranes in the brain. Varying the levels and the symmetry of PS in cell membranes (i.e. on the inside or outside of a membrane) can affect signaling pathways that are central for cell survival (e.g. Akt, protein kinase C, and Raf-1) and neuronal synaptic communication [1]. -

Neural and Behavioural Effects of the Ginkgo Biloba Leaf Extract Egb 761

Wilfrid Laurier University Scholars Commons @ Laurier Theses and Dissertations (Comprehensive) 2009 Neural and Behavioural Effects of the Ginkgo biloba Leaf Extract Egb 761 Elham Satvat Wilfrid Laurier University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.wlu.ca/etd Part of the Behavior and Behavior Mechanisms Commons Recommended Citation Satvat, Elham, "Neural and Behavioural Effects of the Ginkgo biloba Leaf Extract Egb 761" (2009). Theses and Dissertations (Comprehensive). 1070. https://scholars.wlu.ca/etd/1070 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars Commons @ Laurier. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations (Comprehensive) by an authorized administrator of Scholars Commons @ Laurier. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Neural and Behavioural Effects of the Ginkgo biloba Leaf Extract EGb 761 by Elham Satvat Bachelor of Art in Psychology, Wilfrid Laurier University, 2003 Master of Science in Psychology (Brain & Cognition) Wilfrid Laurier University, 2004 DISSERTATION Submitted to the Department of Psychology in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Doctor of Philosophy in Psychology (Brain & Cognition) Wilfrid Laurier University 2009 © Elham Satvat 2009 Library and Bibliotheque et 1*1 Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-49970-2 Our file Notre reference -

Ventnor Botanic Garden

Dinosaurs and plants DAWN REDWOOD – Metasequoia glyptostroboides The discovery of this conifer in Szechuan in 1947 created a The Isle of Wight is one of the most important dinosaur horticultural sensation. It was recognised as a descendant of discovery and excavation sites in the world. More than trees from the Carboniferous period, which means it dates back twenty types have now been found, all within a few miles to a time before even the dinosaurs had evolved. of Ventnor Botanic Garden. CYCADS – Cycas revolute In early Cretaceous times when dinosaurs ruled, plant Cycads were the most frequent plants in a life was abundant but very different from now. Just a few dinosaur landscape. Fossils of their 'dinosaur plants' have survived. Ventnor Botanic Garden distinctive cones – like pineapples, to Ventnor Botanic Garden is which they are related – are found on the fortunate to house some of the Island. Though no longer most important ‘living fossils’ widespread, many species of Cycad thrive that covered the Earth during in warmer climates. There is a Cycad with- the time of the dinosaurs. The Isle of Wight in the Early in the garden that is flowering—this is the Cretaceous period 125 million first flowering Cycad in 250 MILLION years ago years! Can you find it? MAGNOLIA – Magnolia spp GINKGO TREES – Ginkgo biloba This ancient and beautiful group of plants evolved towards the The Ginkgo tree has remained the same over 240 million end of the dinosaur age, and is one of the very first flowering years and its distinctive leaf shape is instantly recognisable plants. -

Telomere Length and TERT Expression Are Associated with Age in Almond (Prunus Dulcis) 2 Katherine M

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.09.25.294074; this version posted September 27, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. 1 Telomere length and TERT expression are associated with age in almond (Prunus dulcis) 2 Katherine M. D’Amico-Willman1,2,¶, Elizabeth Anderson3,¶, Thomas M. Gradziel4, and Jonathan 3 Fresnedo-Ramírez1,2* 4 1 Department of Horticulture and Crop Science, Ohio Agricultural Research and Development 5 Center, The Ohio State University, Wooster, OH 44691 6 2 Center for Applied Plant Sciences, The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH 43210 7 3 College of Wooster, Wooster, OH 44691 8 4 Department of Plant Sciences, University of California, Davis, CA 95616 9 10 *For correspondence ([email protected]) 11 ¶Authors contributed equally 12 13 Abstract 14 While it is well known that all organisms age, our understanding of how aging occurs varies 15 dramatically among species. The aging process in perennial plants is not well defined, yet can 16 have implications on production and yield of valuable fruit and nut crops. Almond, a relevant nut 17 crop, exhibits an age-related disorder known as non-infectious bud failure (BF) that affects 18 vegetative bud development, indirectly affecting kernel-yield. This species and disorder present 19 an opportunity to address aging in a commercially-relevant and vegetatively-propagated, 20 perennial crop threatened by an aging-related disorder. In this study, we tested the hypothesis 21 that telomere length and/or TERT expression can serve as biomarkers of aging in almond using 22 both whole-genome sequencing data and leaf samples collected from distinct age cohorts over a 23 two-year period. -

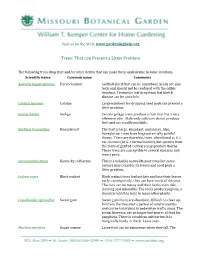

Trees: That Can Present a Litter Problem

Visit us on the Web: www.gardeninghelp.org Trees: That can Present a Litter Problem The following trees drop fruit and/or other debris that can make them undesirable in some locations. Scientific name Common name Comments Aesculus hippocastanum Horsechestnut Golfball-sized fruit can be hazardous. Seeds are also toxic and should not be confused with the edible chestnut. Premature leaf drop from leaf blotch disease can be unsightly. Catalpa speciosa Catalpa Large numbers for dropping seed pods can present a litter problem. Ginkgo biloba Ginkgo Female ginkgo trees produce a fruit that has a very offensive odor. Male-only cultivars do not produce fruit and are readily available. Gleditsia triacanthus Honeylocust The fruit is large, abundant, and messy. Also, honeylocust trees have large potentially painful thorns. There are thornless trees, often listed as G. t. var. inermis (or G. t. forma inermis), but sprouts from the roots of grafted cultivars may produce thorns. These trees are susceptible to several diseases and insect pests. Gymnocladus dioica Kentucky coffeetree This is a valuable native Missouri tree but some owners may consider its leaves and seed pods a litter problem. Juglans nigra Black walnut Black walnut trees leaf out late and lose their leaves early; consequently, they are bare much of the year. The nuts can be messy and their husks stain skin, clothing and sidewalks. The roots produce juglone, a chemical which is toxic to many other plants. Liquidamber styraciflua Sweet gum Sweet gum fruits are abundant, difficult to clean up, fall from the tree over a period of several months and can be hazardous in pedestrian traffic areas. -

Ginkgo Biloba Maidenhair Tree1 Edward F

Fact Sheet ST-273 November 1993 Ginkgo biloba Maidenhair Tree1 Edward F. Gilman and Dennis G. Watson2 INTRODUCTION Ginkgo is practically pest-free, resistant to storm damage, and casts light to moderate shade (Fig. 1). Young trees are often very open but they fill in to form a denser canopy. It makes a durable street tree where there is enough overhead space to accommodate the large size. The shape is often irregular with a large branch or two seemingly forming its own tree on the trunk. But this does not detract from its usefulness as a city tree unless the tree will be growing in a restricted overhead space. If this is the case, select from the narrow upright cultivars such as ‘Princeton Sentry’ and ‘Fairmont’. Ginkgo tolerates most soil, including compacted, and alkaline, and grows slowly to 75 feet or more tall. The tree is easily transplanted and has a vivid yellow fall color which is second to none in brilliance, even in the south. However, leaves fall quickly and the fall color show is short. GENERAL INFORMATION Scientific name: Ginkgo biloba Pronunciation: GINK-go bye-LOE-buh Common name(s): Maidenhair Tree, Ginkgo Family: Ginkgoaceae Figure 1. Middle-aged Maidenhair Tree. USDA hardiness zones: 3 through 8A (Fig. 2) Origin: not native to North America Uses: Bonsai; wide tree lawns (>6 feet wide); drought are common medium-sized tree lawns (4-6 feet wide); Availability: generally available in many areas within recommended for buffer strips around parking lots or its hardiness range for median strip plantings in the highway; specimen; sidewalk cutout (tree pit); residential street tree; tree has been successfully grown in urban areas where air pollution, poor drainage, compacted soil, and/or 1. -

(12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 9,079,047 B2 Kang Et Al

US009079047B2 (12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 9,079,047 B2 Kang et al. (45) Date of Patent: Jul. 14, 2015 (54) COSMETIC COMPOSITION FORSKIN (58) Field of Classification Search WHITENING None See application file for complete search history. (75) Inventors: Hyun Seo Kang, Yongin-si (KR); Seung Hyun Kang, Yongin-si (KR); Ji Hyun Kim, Yongin-si (KR); Yong Joo Na, (56) References Cited Yongin-si (KR); Jun Cheol Cho, U.S. PATENT DOCUMENTS Yongin-si (KR); Byung Guen Chae, Yongin-si (KR) 6,383,525 B1* 5/2002 Hsu et al. ...................... 424,728 2007/0082024 A1* 4/2007 Matsumoto et al. .......... 424/439 (73) Assignee: AMOREPACIFIC CORPORATION 2011/O1893.14 A1* 8/2011 Debaun et al. ................ 424,727 Seoul (KR) FOREIGN PATENT DOCUMENTS (*) Notice: Subject to any disclaimer, the term of this JP 2008081472 A * 4, 2008 patent is extended or adjusted under 35 JP 2010150217 A * 7, 2010 U.S.C. 154(b) by 166 days. KR 2003071893 A * 9, 2003 KR 2004O97764 A * 11, 2004 (21) Appl. No.: 13/398,353 KR 2008044612 A * 5, 2008 (22) Filed: Feb. 16, 2012 * c1tedcited bby examiner (65) Prior Publication Data Primary Examiner — Qiuwen Mi US 2012/O213719 A1 Aug. 23, 2012 (74) Attorney, Agent, or Firm — Nixon & Vanderhye P.C. (30) Foreign Application Priority Data (57) ABSTRACT Feb. 18, 2011 (KR) 10-2011-OO14441 The present invention relates to a cosmetic composition for • Y-s 1- u u wu-a-wy - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - skin whitening containing at least two selected from the group (51) Int. Cl. consisting of a Magnolia -

Recommended Trees to Plant

Recommended Trees to Plant Large Sized Trees (Mature height of more than 45') (* indicates tree form only) Trees in this category require a curb/tree lawn width that measures at least a minimum of 8 feet (area between the stree edge/curb and the sidewalk). Trees should be spaced a minimum of 40 feet apart within the curb/tree lawn. Trees in this category are not compatible with power lines and thus not recommended for planting directly below or near power lines. Norway Maple, Acer platanoides Cleveland Norway Maple, Acer platanoides 'Cleveland' Columnar Norway Maple, Acer Patanoides 'Columnare' Parkway Norway Maple, Acer Platanoides 'Columnarbroad' Superform Norway Maple, Acer platanoides 'Superform' Red Maple, Acer rubrum Bowhall Red Maple, Acer rubrum 'Bowhall' Karpick Red Maple, Acer Rubrum 'Karpick' Northwood Red Maple, Acer rubrum 'Northwood' Red Sunset Red Maple, Acer Rubrum 'Franksred' Sugar Maple, Acer saccharum Commemoration Sugar Maple, Acer saccharum 'Commemoration' Endowment Sugar Maple, Acer saccharum 'Endowment' Green Mountain Sugar Maple, Acer saccharum 'Green Mountain' Majesty Sugar Maple, Acer saccharum 'Majesty' Adirzam Sugar Maple, Acer saccharum 'Adirzam' Armstrong Freeman Maple, Acer x freemanii 'Armstrong' Celzam Freeman Maple, Acer x freemanii 'Celzam' Autumn Blaze Freeman, Acer x freemanii 'Jeffersred' Ruby Red Horsechestnut, Aesculus x carnea 'Briotii' Heritage River Birch, Betula nigra 'Heritage' *Katsura Tree, Cercidiphyllum japonicum *Turkish Filbert/Hazel, Corylus colurna Hardy Rubber Tree, Eucommia ulmoides -

S:\FULLCO~1\HEARIN~1\Committee Print 2018\Henry\Jan. 9 Report

Embargoed for Media Publication / Coverage until 6:00AM EST Wednesday, January 10. 1 115TH CONGRESS " ! S. PRT. 2d Session COMMITTEE PRINT 115–21 PUTIN’S ASYMMETRIC ASSAULT ON DEMOCRACY IN RUSSIA AND EUROPE: IMPLICATIONS FOR U.S. NATIONAL SECURITY A MINORITY STAFF REPORT PREPARED FOR THE USE OF THE COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN RELATIONS UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED FIFTEENTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION JANUARY 10, 2018 Printed for the use of the Committee on Foreign Relations Available via World Wide Web: http://www.gpoaccess.gov/congress/index.html U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 28–110 PDF WASHINGTON : 2018 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Publishing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate Mar 15 2010 04:06 Jan 09, 2018 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5012 Sfmt 5012 S:\FULL COMMITTEE\HEARING FILES\COMMITTEE PRINT 2018\HENRY\JAN. 9 REPORT FOREI-42327 with DISTILLER seneagle Embargoed for Media Publication / Coverage until 6:00AM EST Wednesday, January 10. COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN RELATIONS BOB CORKER, Tennessee, Chairman JAMES E. RISCH, Idaho BENJAMIN L. CARDIN, Maryland MARCO RUBIO, Florida ROBERT MENENDEZ, New Jersey RON JOHNSON, Wisconsin JEANNE SHAHEEN, New Hampshire JEFF FLAKE, Arizona CHRISTOPHER A. COONS, Delaware CORY GARDNER, Colorado TOM UDALL, New Mexico TODD YOUNG, Indiana CHRISTOPHER MURPHY, Connecticut JOHN BARRASSO, Wyoming TIM KAINE, Virginia JOHNNY ISAKSON, Georgia EDWARD J. MARKEY, Massachusetts ROB PORTMAN, Ohio JEFF MERKLEY, Oregon RAND PAUL, Kentucky CORY A. BOOKER, New Jersey TODD WOMACK, Staff Director JESSICA LEWIS, Democratic Staff Director JOHN DUTTON, Chief Clerk (II) VerDate Mar 15 2010 04:06 Jan 09, 2018 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 5904 Sfmt 5904 S:\FULL COMMITTEE\HEARING FILES\COMMITTEE PRINT 2018\HENRY\JAN. -

Russia in the Middle East: a New Front in the Information War?

Russia in the Middle East: A New Front in the Information War? By Donald N. Jensen Summary Russia uses its information warfare capability as a tactic, especially its RT Arabic and Sputnik news services, to advance its foreign policy goals in the Middle East: become a great power in the region; reduce the role of the United States; prop up allies such as Bashir al- Assad in Syria, and fight terrorism. Evidence suggests that while Russian media narratives are disseminated broadly in the region by traditional means and online, outside of Syria its impact has been limited. The ability of regional authoritarian governments to control the information their societies receive, cross cutting political pressures, the lack of longstanding ethnic and cultural ties with Russia, and widespread doubts about Russian intentions will make it difficult for Moscow to use information operations as an effective tool should it decide to maintain an enhanced permanent presence in the region. Introduction Russian assessments of the international system make it clear that the Kremlin considers the country to be engaged in full-scale information warfare. This is reflected in Russia’s latest military doctrine, approved December 2014, comments by public officials, and Moscow’s aggressive use of influence operations.1 The current Russian practice of information warfare combines a number of tried and tested tools of influence with a new embrace of modern technology and capabilities such as the Internet. Some underlying objectives, guiding principles and state activity are broadly recognizable as reinvigorated aspects of subversion campaigns from the Cold War era and earlier. But Russia also has invested hugely in updating the principles of subversion. -

LIVESTREAM: Space.Com

GRACE EXHIBITION SPACE for INTERNATIONAL PERFORMANCE ART 501©3 www.Grace-Exhibition-Space.com SPRING 2021 … a slice of our world March 12 – May 28, 2021 PRESS RELEASE link Travel and meeting in person are at the heart of the international community of performance artists. In this time of the pandemic, the personal sharing of ideas and communication has been impossible. At the suggestion of Belfast performance artist, Sinead O'Donnell, during a panel hosted by Boston-based performance artist Marilyn Arsem, Grace Exhibition Space offered to fill-in this absence with a series of performance art events offered live from around the world LIVESTREAM: www.grace-exhibition- GRACE: space.com/graceStreamingPerformance.php Opened in 2006, Grace Exhibition Space is devoted exclusively to Performance Art. We offer an opportunity to experience visceral and challenging works by the current generation of international performance artists whether emerging, mid-career or established. Our BBEYOND events are presented on the floor, not on a stage, dissolving the [BELFAST, NORTHERN IRELAND] boundary between artist and viewer. This is how performance art is meant to be experienced and our mission is the glorification of Celebrating 20 years! performance art. Grace Exhibition Space presents over 30 curated live performance art exhibitions each year, showcasing new work by more than 400 performance artists from across the United States and the world since 2006. THURSDAY, MARCH 18, 2021 Grace Exhibition Space for International Performance Art Space IRS tax-exempt -

Gymnosperms on the EDGE Félix Forest1, Justin Moat 1,2, Elisabeth Baloch1, Neil A

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Gymnosperms on the EDGE Félix Forest1, Justin Moat 1,2, Elisabeth Baloch1, Neil A. Brummitt3, Steve P. Bachman 1,2, Stef Ickert-Bond 4, Peter M. Hollingsworth5, Aaron Liston6, Damon P. Little7, Sarah Mathews8,9, Hardeep Rai10, Catarina Rydin11, Dennis W. Stevenson7, Philip Thomas5 & Sven Buerki3,12 Driven by limited resources and a sense of urgency, the prioritization of species for conservation has Received: 12 May 2017 been a persistent concern in conservation science. Gymnosperms (comprising ginkgo, conifers, cycads, and gnetophytes) are one of the most threatened groups of living organisms, with 40% of the species Accepted: 28 March 2018 at high risk of extinction, about twice as many as the most recent estimates for all plants (i.e. 21.4%). Published: xx xx xxxx This high proportion of species facing extinction highlights the urgent action required to secure their future through an objective prioritization approach. The Evolutionary Distinct and Globally Endangered (EDGE) method rapidly ranks species based on their evolutionary distinctiveness and the extinction risks they face. EDGE is applied to gymnosperms using a phylogenetic tree comprising DNA sequence data for 85% of gymnosperm species (923 out of 1090 species), to which the 167 missing species were added, and IUCN Red List assessments available for 92% of species. The efect of diferent extinction probability transformations and the handling of IUCN data defcient species on the resulting rankings is investigated. Although top entries in our ranking comprise species that were expected to score well (e.g. Wollemia nobilis, Ginkgo biloba), many were unexpected (e.g.