The Production of Consonant Harmony in Child Speech

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pg. 5 CHAPTER-2: MECHANISM of SPEECH PRODUCTION AND

Acoustic Analysis for Comparison and Identification of Normal and Disguised Speech of Individuals CHAPTER-2: MECHANISM OF SPEECH PRODUCTION AND LITERATURE REVIEW 2.1. Anatomy of speech production Speech is the vocal aspect of communication made by human beings. Human beings are able to express their ideas, feelings and emotions to the listener through speech generated using vocal articulators (NIDCD, June 2010). Development of speech is a constant process and requires a lot of practice. Communication is a string of events which allows the speaker to express their feelings and emotions and the listener to understand them. Speech communication is considered as a thought that is transformed into language for expression. Phil Rose & James R Robertson (2002) mentioned that voices of individuals are complex in nature. They aid in providing vital information related to sex, emotional state or age of the speaker. Although evidence from DNA always remains headlines, DNA can‟t talk. It can‟t be recorded planning, carrying out or confessing to a crime. It can‟t be so apparently directly incriminating. Perhaps, it is these features that contribute to interest and importance of forensic speaker identification. Speech signal is a multidimensional acoustic wave (as seen in figure 2.1.) which provides information about the words or message being spoken, speaker identity, language spoken, physical and mental health, race, age, sex, education level, religious orientation and background of an individual (Schetelig T. & Rabenstein R., May 1998). pg. 5 Acoustic Analysis for Comparison and Identification of Normal and Disguised Speech of Individuals Figure 2.1.: Representation of properties of sound wave (Courtesy "Waves". -

1 Consonant Harmony in Child Language

1 Consonant Harmony in Child Language: An Optimality-theoretic Account* Heather Goad Department of Linguistics, McGill University [email protected] Ms. dated 1995. Currently in press in S.J. Hannahs & M. Young-Scholten Focus on phonological acquisition. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 113-142. Abstract An analysis is provided of the consonant harmony (CH) patterns exhibited in the speech of one child, Amahl at Stage 1 (data from Smith 1973). It is argued that the standard rule-based analysis which involves Coronal underspecification and planar segregation is not tenable. First, the data reveal an underspecification paradox: coronal consonants are targets for CH and should thus be unspecified for Coronal. However, they also trigger harmony, in words where the targets are liquids. Second, the data are not consistent with planar segregation, as one harmony pattern is productive beyond the point when AmahlÕs grammar satisfies the requirements for planar segregation (set forth in McCarthy 1989). An alternative analysis is proposed within the constraint-based framework of Optimality Theory (Prince & Smolensky 1993). It is argued that CH follows from the relative ranking of constraints which parse place features and those which align features with the edges of the prosodic word. With the constraints responsible for parsing and aligning Labial and Dorsal ranked above those responsible for parsing and aligning Coronal, the dual behaviour of coronals can be captured. The effect of planar segregation follows from other independently motivated constraints which force alignment to be satisfied through copying of segmental material, not through spreading. Keywords: first language acquisition, consonant harmony, underspecification paradox 1. -

Phonological Use of the Larynx: a Tutorial Jacqueline Vaissière

Phonological use of the larynx: a tutorial Jacqueline Vaissière To cite this version: Jacqueline Vaissière. Phonological use of the larynx: a tutorial. Larynx 97, 1994, Marseille, France. pp.115-126. halshs-00703584 HAL Id: halshs-00703584 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00703584 Submitted on 3 Jun 2012 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Vaissière, J., (1997), "Phonological use of the larynx: a tutorial", Larynx 97, Marseille, 115-126. PHONOLOGICAL USE OF THE LARYNX J. Vaissière UPRESA-CNRS 1027, Institut de Phonétique, Paris, France larynx used as a carrier of paralinguistic information . RÉSUMÉ THE PRIMARY FUNCTION OF THE LARYNX Cette communication concerne le rôle du IS PROTECTIVE larynx dans l'acte de communication. Toutes As stated by Sapir, 1923, les langues du monde utilisent des physiologically, "speech is an overlaid configurations caractéristiques du larynx, aux function, or to be more precise, a group of niveaux segmental, lexical, et supralexical. Nous présentons d'abord l'utilisation des différents types de phonation pour distinguer entre les consonnes et les voyelles dans les overlaid functions. It gets what service it can langues du monde, et également du larynx out of organs and functions, nervous and comme lieu d'articulation des glottales, et la muscular, that come into being and are production des éjectives et des implosives. -

5 Phonology Florian Lionnet and Larry M

5 Phonology Florian Lionnet and Larry M. Hyman 5.1. Introduction The historical relation between African and general phonology has been a mutu- ally beneficial one: the languages of the African continent provide some of the most interesting and, at times, unusual phonological phenomena, which have con- tributed to the development of phonology in quite central ways. This has been made possible by the careful descriptive work that has been done on African lan- guages, by linguists and non-linguists, and by Africanists and non-Africanists who have peeked in from time to time. Except for the click consonants of the Khoisan languages (which spill over onto some neighboring Bantu languages that have “borrowed” them), the phonological phenomena found in African languages are usually duplicated elsewhere on the globe, though not always in as concen- trated a fashion. The vast majority of African languages are tonal, and many also have vowel harmony (especially vowel height harmony and advanced tongue root [ATR] harmony). Not surprisingly, then, African languages have figured dispro- portionately in theoretical treatments of these two phenomena. On the other hand, if there is a phonological property where African languages are underrepresented, it would have to be stress systems – which rarely, if ever, achieve the complexity found in other (mostly non-tonal) languages. However, it should be noted that the languages of Africa have contributed significantly to virtually every other aspect of general phonology, and that the various developments of phonological theory have in turn often greatly contributed to a better understanding of the phonologies of African languages. Given the considerable diversity of the properties found in different parts of the continent, as well as in different genetic groups or areas, it will not be possible to provide a complete account of the phonological phenomena typically found in African languages, overviews of which are available in such works as Creissels (1994) and Clements (2000). -

A Typology of Consonant Agreement As Correspondence

A TYPOLOGY OF CONSONANT AGREEMENT AS CORRESPONDENCE SHARON ROSE RACHEL WALKER University of California, San Diego University of Southern California This article presents a typology of consonant harmony or LONG DISTANCE CONSONANT AGREEMENT that is analyzed as arisingthroughcorrespondence relations between consonants rather than feature spreading. The model covers a range of agreement patterns (nasal, laryngeal, liquid, coronal, dorsal) and offers several advantages. Similarity of agreeing consonants is central to the typology and is incorporated directly into the constraints drivingcorrespondence. Agreementby correspon- dence without feature spreadingcaptures the neutrality of interveningsegments,which neither block nor undergo. Case studies of laryngeal agreement and nasal agreement are presented, demon- stratingthe model’s capacity to capture varyingdegreesof similarity crosslinguistically.* 1. INTRODUCTION. The action at a distance that is characteristic of CONSONANT HAR- MONIES stands as a pivotal problem to be addressed by phonological theory. Consider the nasal alternations in the Bantu language, Kikongo (Meinhof 1932, Dereau 1955, Webb 1965, Ao 1991, Odden 1994, Piggott 1996). In this language, the voiced stop in the suffix [-idi] in la is realized as [ini] in 1b when preceded by a nasal consonant at any distance in the stem constituent, consistingof root and suffixes. (1) a. m-[bud-idi]stem ‘I hit’ b. tu-[kun-ini]stem ‘we planted’ n-[suk-idi]stem ‘I washed’ tu-[nik-ini]stem ‘we ground’ In addition to the alternation in 1, there are no Kikongo roots containing a nasal followed by a voiced stop, confirmingthat nasal harmony or AGREEMENT, as we term it, also holds at the root level as a MORPHEME STRUCTURE CONSTRAINT (MSC). -

Relations Between Speech Production and Speech Perception: Some Behavioral and Neurological Observations

14 Relations between Speech Production and Speech Perception: Some Behavioral and Neurological Observations Willem J. M. Levelt One Agent, Two Modalities There is a famous book that never appeared: Bever and Weksel (shelved). It contained chapters by several young Turks in the budding new psycho- linguistics community of the mid-1960s. Jacques Mehler’s chapter (coau- thored with Harris Savin) was entitled “Language Users.” A normal language user “is capable of producing and understanding an infinite number of sentences that he has never heard before. The central problem for the psychologist studying language is to explain this fact—to describe the abilities that underlie this infinity of possible performances and state precisely how these abilities, together with the various details . of a given situation, determine any particular performance.” There is no hesi tation here about the psycholinguist’s core business: it is to explain our abilities to produce and to understand language. Indeed, the chapter’s purpose was to review the available research findings on these abilities and it contains, correspondingly, a section on the listener and another section on the speaker. This balance was quickly lost in the further history of psycholinguistics. With the happy and important exceptions of speech error and speech pausing research, the study of language use was factually reduced to studying language understanding. For example, Philip Johnson-Laird opened his review of experimental psycholinguistics in the 1974 Annual Review of Psychology with the statement: “The fundamental problem of psycholinguistics is simple to formulate: what happens if we understand sentences?” And he added, “Most of the other problems would be half way solved if only we had the answer to this question.” One major other 242 W. -

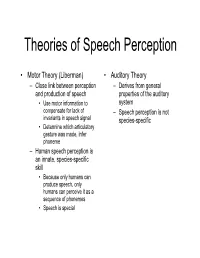

Theories of Speech Perception

Theories of Speech Perception • Motor Theory (Liberman) • Auditory Theory – Close link between perception – Derives from general and production of speech properties of the auditory • Use motor information to system compensate for lack of – Speech perception is not invariants in speech signal species-specific • Determine which articulatory gesture was made, infer phoneme – Human speech perception is an innate, species-specific skill • Because only humans can produce speech, only humans can perceive it as a sequence of phonemes • Speech is special Wilson & friends, 2004 • Perception • Production • /pa/ • /pa/ •/gi/ •/gi/ •Bell • Tap alternate thumbs • Burst of white noise Wilson et al., 2004 • Black areas are premotor and primary motor cortex activated when subjects produced the syllables • White arrows indicate central sulcus • Orange represents areas activated by listening to speech • Extensive activation in superior temporal gyrus • Activation in motor areas involved in speech production (!) Wilson and colleagues, 2004 Is categorical perception innate? Manipulate VOT, Monitor Sucking 4-month-old infants: Eimas et al. (1971) 20 ms 20 ms 0 ms (Different Sides) (Same Side) (Control) Is categorical perception species specific? • Chinchillas exhibit categorical perception as well Chinchilla experiment (Kuhl & Miller experiment) “ba…ba…ba…ba…”“pa…pa…pa…pa…” • Train on end-point “ba” (good), “pa” (bad) • Test on intermediate stimuli • Results: – Chinchillas switched over from staying to running at about the same location as the English b/p -

Appendix B: Muscles of the Speech Production Mechanism

Appendix B: Muscles of the Speech Production Mechanism I. MUSCLES OF RESPIRATION A. MUSCLES OF INHALATION (muscles that enlarge the thoracic cavity) 1. Diaphragm Attachments: The diaphragm originates in a number of places: the lower tip of the sternum; the first 3 or 4 lumbar vertebrae and the lower borders and inner surfaces of the cartilages of ribs 7 - 12. All fibers insert into a central tendon (aponeurosis of the diaphragm). Function: Contraction of the diaphragm draws the central tendon down and forward, which enlarges the thoracic cavity vertically. It can also elevate to some extent the lower ribs. The diaphragm separates the thoracic and the abdominal cavities. 2. External Intercostals Attachments: The external intercostals run from the lip on the lower border of each rib inferiorly and medially to the upper border of the rib immediately below. Function: These muscles may have several functions. They serve to strengthen the thoracic wall so that it doesn't bulge between the ribs. They provide a checking action to counteract relaxation pressure. Because of the direction of attachment of their fibers, the external intercostals can raise the thoracic cage for inhalation. 3. Pectoralis Major Attachments: This muscle attaches on the anterior surface of the medial half of the clavicle, the sternum and costal cartilages 1-6 or 7. All fibers come together and insert at the greater tubercle of the humerus. Function: Pectoralis major is primarily an abductor of the arm. It can, however, serve as a supplemental (or compensatory) muscle of inhalation, raising the rib cage and sternum. (In other words, breathing by raising and lowering the arms!) It is mentioned here chiefly because it is encountered in the dissection. -

Illustrating the Production of the International Phonetic Alphabet

INTERSPEECH 2016 September 8–12, 2016, San Francisco, USA Illustrating the Production of the International Phonetic Alphabet Sounds using Fast Real-Time Magnetic Resonance Imaging Asterios Toutios1, Sajan Goud Lingala1, Colin Vaz1, Jangwon Kim1, John Esling2, Patricia Keating3, Matthew Gordon4, Dani Byrd1, Louis Goldstein1, Krishna Nayak1, Shrikanth Narayanan1 1University of Southern California 2University of Victoria 3University of California, Los Angeles 4University of California, Santa Barbara ftoutios,[email protected] Abstract earlier rtMRI data, such as those in the publicly released USC- TIMIT [5] and USC-EMO-MRI [6] databases. Recent advances in real-time magnetic resonance imaging This paper presents a new rtMRI resource that showcases (rtMRI) of the upper airway for acquiring speech production these technological advances by illustrating the production of a data provide unparalleled views of the dynamics of a speaker’s comprehensive set of speech sounds present across the world’s vocal tract at very high frame rates (83 frames per second and languages, i.e. not restricted to English, encoded as conso- even higher). This paper introduces an effort to collect and nant and vowel symbols in the International Phonetic Alphabet make available on-line rtMRI data corresponding to a large sub- (IPA), which was devised by the International Phonetic Asso- set of the sounds of the world’s languages as encoded in the ciation as a standardized representation of the sounds of spo- International Phonetic Alphabet, with supplementary English ken language [7]. These symbols are meant to represent unique words and phonetically-balanced texts, produced by four promi- speech sounds, and do not correspond to the orthography of any nent phoneticians, using the latest rtMRI technology. -

The Effects of Phonological Processes on the Speech Intelligibility of Young Children

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 10-20-1994 The Effects of Phonological Processes on the Speech Intelligibility of Young Children Susanne Shotola-Hardt Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the Speech and Rhetorical Studies Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Shotola-Hardt, Susanne, "The Effects of Phonological Processes on the Speech Intelligibility of Young Children" (1994). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 4780. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.6664 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. THESIS APPROVAL The abstract and thesis of Susanne Shotola-Hardt for the Master of Science in Speech Communication: Speech and Hearing Sciences were presented October 20, 1994, and accepted by the thesis committee and the department. COMMITTEE APPROVALS: .. \\ ....___ ____ ; --J6~n McMahon Sheldon Maron Representative, Office of Graduate Studies DEPARTMENT APPROVAL: ""' A * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * ACCEPTED FOR PORTLAND STATE UNIVERSITY BY THE LIBRARY b on £!luve-4* ~ /99</: . ABSTRACT An abstract of the thesis of Susanne Shotola-Hardt for the Master of Science in Speech Communication: Speech and Hearing Sciences presented October 20, 1994. Title: The Effects of Phonological Processes on the Speech Intelligibility of Young Children. The purpose of this study was to explore the relationship between occurrence of 10 phonological processes, singly and in groups, with mean percentage of intelligibility of connected speech samples. -

Articulatory Phonetics

Articulatory Phonetics Lecturer: Dr Anna Sfakianaki HY578 Digital Speech Signal Processing Spring Term 2016-17 CSD University of Crete What is Phonetics? n Phonetics is a branch of Linguistics that systematically studies the sounds of human speech. 1. How speech sounds are produced Production (Articulation) 2. How speech sounds are transmitted Acoustics 3. How speech sounds are received Perception It is an interdisciplinary subject, theoretical as much as experimental. Why do speech engineers need phonetics? n An engineer working on speech signal processing usually ignores the linguistic background of the speech he/she analyzes. (Olaszy, 2005) ¡ How was the utterance planned in the speaker’s brain? ¡ How was it produced by the speaker’s articulation organs? ¡ What sort of contextual influences did it receive? ¡ How will the listener decode the message? Phonetics in Speech Engineering Combined knowledge of articulatory gestures and acoustic properties of speech sounds Categorization of speech sounds Segmentation Speech Database Annotation Algorithms Speech Recognition Speech Synthesis Phonetics in Speech Engineering Speech • diagnosis Disorders • treatment Pronunciation • L2 Teaching Tools • Foreign languages Speech • Hearing aids Intelligibility Enhancement • Other tools A week with a phonetician… n Tuesday n Thursday Articulatory Phonetics Acoustic Phonetics ¡ Speech production ¡ Formants ¡ Sound waves ¡ Fundamental Frequency ¡ Places and manners of articulation ¡ Acoustics of Vowels n Consonants & Vowels n Articulatory vs Acoustic charts ¡ Waveforms of consonants - VOT ¡ Acoustics of Consonants n Formant Transitions ¡ Suprasegmentals n Friday More Acoustic Phonetics… ¡ Interpreting spectrograms ¡ The guessing game… ¡ Individual Differences Peter Ladefoged Home Page: n Professor UCLA (1962-1991) http://www.linguistics.ucla.edu/people/ladefoge/ n Travelled in Europe, Africa, India, China, Australia, etc. -

78. 78. Nasal Harmony Nasal Harmony

Bibliographic Details The Blackwell Companion to Phonology Edited by: Marc van Oostendorp, Colin J. Ewen, Elizabeth Hume and Keren Rice eISBN: 9781405184236 Print publication date: 2011 78. Nasal Harmony RACHEL WWALKER Subject Theoretical Linguistics » Phonology DOI: 10.1111/b.9781405184236.2011.00080.x Sections 1 Nasal vowel–consonant harmony with opaque segments 2 Nasal vowel–consonant harmony with transparent segments 3 Nasal consonant harmony 4 Directionality 5 Conclusion ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Notes REFERENCES Nasal harmony refers to phonological patterns where nasalization is transmitted in long-distance fashion. The long-distance nature of nasal harmony can be met by the transmission of nasalization either to a series of segments or to a non-adjacent segment. Nasal harmony usually occurs within words or a smaller domain, either morphologically or prosodically defined. This chapter introduces the chief characteristics of nasal harmony patterns with exemplification, and highlights related theoretical themes. It focuses primarily on the different roles that segments can play in nasal harmony, and the typological properties to which they give rise. The following terminological conventions will be assumed. A trigger is a segment that initiates nasal harmony. A target is a segment that undergoes harmony. An opaque segment or blocker halts nasal harmony. A transparent segment is one that does not display nasalization within a span of nasal harmony, but does not halt harmony from transmitting beyond it. Three broad categories of nasal harmony are considered in this chapter. They are (i) nasal vowel–consonant harmony with opaque segments, (ii) nasal vowel– consonant harmony with transparent segments, and (iii) nasal consonant harmony. Each of these groups of systems show characteristic hallmarks.