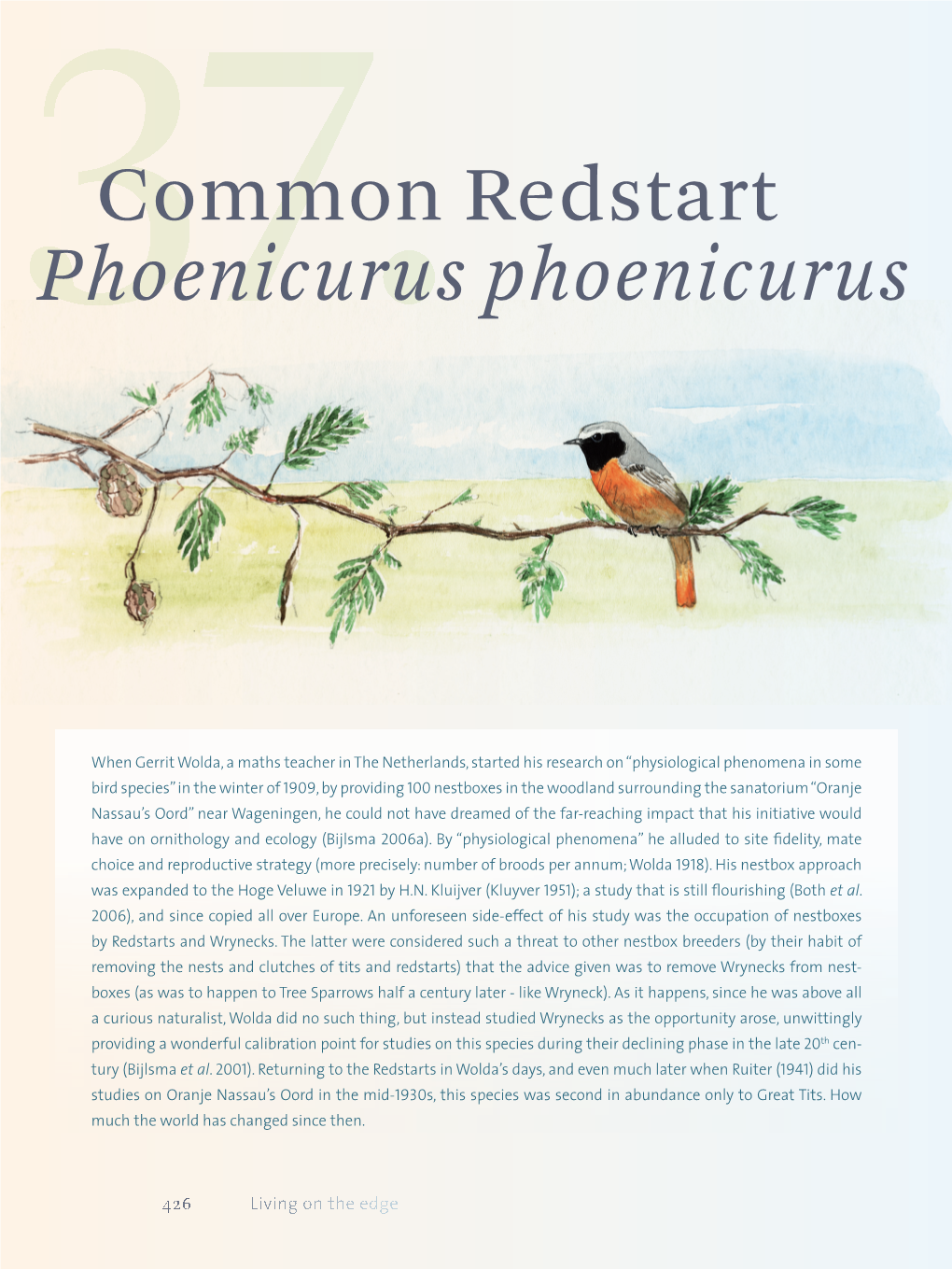

Common Redstart Phoenicurus Phoenicurus 427

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Passerines: Perching Birds

3.9 Orders 9: Passerines – perching birds - Atlas of Birds uncorrected proofs 3.9 Atlas of Birds - Uncorrected proofs Copyrighted Material Passerines: Perching Birds he Passeriformes is by far the largest order of birds, comprising close to 6,000 P Size of order Cardinal virtues Insect-eating voyager Multi-purpose passerine Tspecies. Known loosely as “perching birds”, its members differ from other Number of species in order The Northern or Common Cardinal (Cardinalis cardinalis) The Common Redstart (Phoenicurus phoenicurus) was The Common Magpie (Pica pica) belongs to the crow family orders in various fine anatomical details, and are themselves divided into suborders. Percentage of total bird species belongs to the cardinal family (Cardinalidae) of passerines. once thought to be a member of the thrush family (Corvidae), which includes many of the larger passerines. In simple terms, however, and with a few exceptions, passerines can be described Like the various tanagers, grosbeaks and other members (Turdidae), but is now known to belong to the Old World Like many crows, it is a generalist, with a robust bill adapted of this diverse group, it has a thick, strong bill adapted to flycatchers (Muscicapidae). Its narrow bill is adapted to to feeding on anything from small animals to eggs, carrion, as small birds that sing. feeding on seeds and fruit. Males, from whose vivid red eating insects, and like many insect-eaters that breed in insects, and grain. Crows are among the most intelligent of The word passerine derives from the Latin passer, for sparrow, and indeed a sparrow plumage the family is named, are much more colourful northern Europe and Asia, this species migrates to Sub- birds, and this species is the only non-mammal ever to have is a typical passerine. -

The Importance of Sparse Vegetation for the Common Redstart Phoenicurus Phoenicurus

J Ornithol (2010) 151:297–307 DOI 10.1007/s10336-009-0455-6 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Habitat structure versus food abundance: the importance of sparse vegetation for the common redstart Phoenicurus phoenicurus Nicolas Martinez • Lukas Jenni • Eric Wyss • Niklaus Zbinden Received: 29 October 2008 / Revised: 3 September 2009 / Accepted: 21 September 2009 / Published online: 8 October 2009 Ó Dt. Ornithologen-Gesellschaft e.V. 2009 Abstract As many other birds breeding in agricultural surfaces with sparse vegetation than unoccupied control areas, the common redstart declined strongly in many sites. Redstarts made almost five times more hunting flights Central European countries over the last 60 years. The into experimentally established ruderal vegetation strips destruction of traditionally managed orchards, an important than into adjacent unmown meadows. No difference was breeding habitat in Central Europe, is a relevant cause. An observed when the meadow was freshly mown. Vegetation additional factor for the decline of this species could be the height and the proportion of open ground surface correctly intensified management of the ground vegetation in orch- predicted the vegetation type for hunting in 77% of the ards through reducing food availability and lowering prey cases. Experiments in aviaries offering two types of sparse detectability and accessibility. In this study we examined vegetation and a dense meadow supported the results of the the importance of surfaces with sparse vegetation for the field experiments. Even a four-fold increase of the food location of redstart territories and for foraging. To validate abundance in the meadow did not lead to a noticeable the results of these field studies we made habitat-choice change in preference for the sparse vegetation types. -

AIRONE CENERINO Ardea Cinerea the Grey Heron (Ardea Cinerea

AIRONE CENERINO Ardea cinerea The Grey Heron (Ardea cinerea ) is a wading bird of the heron family Ardeidae . The Grey Heron is a large bird, standing 1 m tall, and it has a 1.5 m wingspan. It is the largest European heron. Its plumage is largely grey above, and off-white below. It has a powerful yellow bill, which is brighter in breeding adults. It has a slow flight, with its long neck retracted (S-shaped). This is characteristic of herons and bitterns, and distinguishes them from storks, cranes and spoonbills, which extend their necks This species breeds in colonies in trees close to lakes or other wetlands, although it will also nest in reed beds. It builds a bulky stick nest. It feeds in shallow water, spearing fish or frogs with its long, sharp bill. Herons will also take small mammals and birds. It will often wait motionless for prey, or slowly stalk its victim. The call is a loud croaking "fraaank". This species is very similar to the American Great Blue Heron. The Australian White-faced Heron is often incorrectly called Grey Heron ALLODOLA Alauda arvensis The Skylark (Alauda arvensis ) is a small passerine bird. It breeds across most of Europe and Asia and in the mountains of north Africa. It is mainly resident in the west of its range, but eastern populations of are more migratory, moving further south in winter. Even in the milder west of its range, many birds move to lowlands and the coast in winter. Asian birds appear as vagrants in Alaska; this bird has also been introduced in Hawaii and western North America. -

Common Redstart

Redstart The Redstart appears very like a Robin in many of its habits and actions. It has the same general carriage, and chat-like behaviour, and is the same length but slightly slimmer and lighter. The orange-red tail, from which it gets its name ("start" is an old word for "tail"), is frequently quivered. Male Female The Redstart is a summer visitor throughout most of Europe and western Asia (east to Lake Baikal), and also in northwest Africa in Morocco. It winters in central Africa and Arabia, south of the Sahara Desert but north of the Equator. It is widespread as a breeding bird in Great Britain, particularly in upland broadleaf woodlands and hedgerow trees, but in Ireland it is very local. The males first arrive in early to mid April, often a few days in advance of the females. Five or six light blue eggs are laid during May, with a second brood in mid summer in the south of the breeding range. It departs for Africa between mid-August and early October. It often feeds like a flycatcher, making aerial sallies after passing insects, and most of its food consists of winged insects. The call is chat-like and the alarm a plaintive single note, wheet, like that of many other chats. Habitat Redstarts prefer open mature birch and oak woodland with a high horizontal visibility and low amounts of shrub and understorey especially where the trees are old enough to have holes suitable for its nest. They prefer to nest on the edge of woodland clearings. -

Madrid Hot Birding, Closer Than Expected

Birding 04-06 Spain2 2/9/06 1:50 PM Page 38 BIRDING IN THE OLD WORLD Madrid Hot Birding, Closer Than Expected adrid is Spain’s capital, and it is also a capital place to find birds. Spanish and British birders certainly know M this, but relatively few American birders travel to Spain Howard Youth for birds. Fewer still linger in Madrid to sample its avian delights. Yet 4514 Gretna Street 1 at only seven hours’ direct flight from Newark or 8 ⁄2 from Miami, Bethesda, Maryland 20814 [email protected] Madrid is not that far off. Friendly people, great food, interesting mu- seums, easy city transit, and great roads make central Spain a great va- cation destination. For a birder, it can border on paradise. Spain holds Europe’s largest populations of many species, including Spanish Imperial Eagle (Aquila heliaca), Great (Otis tarda) and Little (Tetrax tetrax) Bustards, Eurasian Black Vulture (Aegypius monachus), Purple Swamphen (Porphyrio porphyrio), and Black Wheatear (Oenanthe leucura). All of these can be seen within Madrid Province, the fo- cus of this article, all within an hour’s drive of downtown. The area holds birding interest year-round. Many of northern Europe’s birds winter in Spain, including Common Cranes (which pass through Madrid in migration), an increasing number of over-wintering European White Storks (Ciconia ciconia), and a wide variety of wa- terfowl. Spring comes early: Barn Swallows appear by February, and many Africa-wintering water birds arrive en masse in March. Other migrants, such as European Bee-eater (Merops apiaster), Common Nightingale (Luscinia megarhynchos), and Golden Oriole (Oriolus ori- olous), however, rarely arrive before April. -

Common Redstart) Phoenicurus Phoenicurus

374 The Birds of Gloucestershire Species accounts 375 Redstart (Common Redstart) Phoenicurus phoenicurus Atlases, no doubt due at least in part to the 1968 Sahel drought, but 2007–11 Atlas fieldwork Gloucestershire trends UK population trends more recently there has been an erratic recovery and there are now % of tetrads in which UK conservation status: Number of tetrads in which recorded (max 683) Occupied 10 km squares (max 26) estimated to be about 100,000 pairs in the country. recorded (1st hour of TTV) Amber 1 Swaine noted that Redstarts bred ‘throughout the county’ and that the decline recorded in much of southern and eastern England Total Confirmed Probable Possible Present 1968–71 1981–84 1988–91 2007–11 1988–91 2008–11 Long term Short term prior to 1940 had not affected Gloucestershire until much later. Breeding 200 49 25 83 43 26 20 23 10.7 6.3 +27% +7% However there appeared to have been a considerable decline in the Winter 0 0 0 – – Thames Area and possibly the Cotswolds just prior to 1980. The maps show that Redstarts were recorded quite widely in the county during the current atlas fieldwork, although breeding records were concentrated in the three very different areas that have been the SO 6 7 8 9 0 1 2 SP SO 6 7 8 9 0 1 2 SP strongholds here in recent years: the sheep-rearing country of Bird Present 0.01–0.25 4 Possible 4 4 0.26–0.50 4 the high wold east of the Cotswold scarp, with its stone walls and Breeding 0.51–0.75 scattered bushes (2003–07 Cotswolds Atlas); the Forest of Dean with Probable Breeding 0.76–2.00 its mature oaks; and the floodplain of the Severn near Ashleworth Confirmed 3 3 3 3 with its willow pollards, where populations are probably at their Breeding highest density in the county albeit in a small area. -

Competition with a Host Nestling for Parental Provisioning Imposes Recoverable

G Model BEPROC-2481; No. of Pages 6 ARTICLE IN PRESS Behavioural Processes xxx (2012) xxx–xxx Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Behavioural Processes journa l homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/behavproc Competition with a host nestling for parental provisioning imposes recoverable costs on parasitic cuckoo chick’s growth a b c d e,∗ Nikoletta Geltsch , Márk E. Hauber , Michael G. Anderson , Miklós Bán , Csaba Moskát a Department of Ecology, University of Szeged, Közép fasor 52, Szeged, H-6726, Hungary b Department of Psychology, Hunter College and the Graduate Center of the City University of New York, 695 Park Avenue, New York, NY 10065, USA c Ecology and Conservation Group, Institute of Natural Science, Massey University, Albany Campus, Auckland, New Zealand d Behavioural Ecology Research Group, Department of Evolutionary Zoology, University of Debrecen, Egyetem tér 1, H-3010 Debrecen, Hungary e MTA-ELTE-MTM Ecology Research Group, Biological Institute, Eötvös Lóránd University, Pázmány Péter sétány 1/C., H-1117 Budapest, Hungary a r t i c l e i n f o a b s t r a c t Article history: Chicks of the brood parasitic common cuckoo (Cuculus canorus) typically monopolize host parental care Received 19 August 2011 by evicting all eggs and nestmates from the nest. To assess the benefits of parasitic eviction behaviour Received in revised form 28 February 2012 throughout the full nestling period, we generated mixed broods of one cuckoo and one great reed war- Accepted 6 April 2012 bler (Acrocephalus arundinaceus) to study how hosts divide care between own and parasitic young. -

Limited Flexibility in Departure Timing of Migratory Passerines at the East

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Limited fexibility in departure timing of migratory passerines at the East‑Mediterranean fyway Yaara Aharon‑Rotman 1,2*, Gidon Perlman3, Yosef Kiat3,4, Tal Raz1, Amir Balaban3 & Takuya Iwamura1,5* The rapid pace of current global warming lead to the advancement of spring migration in the majority of long‑distance migratory bird species. While data on arrival timing to breeding grounds in Europe is plentiful, information from the African departure sites are scarce. Here we analysed changes in arrival timing at a stopover site in Israel and any links to Enhanced Vegetation Index (EVI) on the species‑ specifc African non‑breeding range in three migratory passerines between 2000–2017. Diferences in wing length between early and late arriving individuals were also examined as a proxy for migration distance. We found that male redstart, but not females, advanced arrival to stopover site, but interestingly, not as a response to EVI phenology. Blackcap and barred warbler did not shift arrival timing signifcantly, although the arrival of blackcap was dependent on EVI. Barred warbler from the early arrival phase had longer wings, suggesting diferent populations. Our study further supports the existence species‑specifc migration decisions and inter‑sexual diferences, which may be triggered by both exogenous (local vegetation condition) and endogenous cues. Given rapid rate of changes in environmental conditions at higher latitudes, some migrants may experience difculty in the race to match global changes to ensure their survival. Current global warming is occurring at an asymmetrical pace, with greater increase in temperatures at higher northern latitudes1,2. -

Scotland in Style

SCOTLAND IN STYLE MAY 1-10, 2020 ©2019 Please note this tour may be taken in connection with Wild & Ancient Britain with Ireland cruise , May 11-26, 2020. Cairngorms National Park © Andrew Whittaker This short, one hotel tour provides an enormously varied and comprehensive taste of all that the bonnie Scottish Highlands have to offer. During our seven full days based around Strathspey and the spectacular Cairngorms National Park, there will be a varied and flexible daily program of events. Although the main focus is on birding excursions, we will be centrally located to visit many fine castles, battlefields, and sites of historical significance, plus we’ll enjoy a guided visit to a famous Scotch single malt whisky distillery. Scotland in Style, Page 2 The Highlands scenery is the most dramatic in the British Isles: the highest peaks in Britain; extensive remote moorlands; large tracts of ancient woodland of Caledonian Pines; stunning coastal scenery of cliffs, inlets, lochs, and offshore islands; and vast tracts of prehistoric peat bog and fast-flowing, crystal clear rivers. We will target localized and rare specialties such as Eurasian Capercaillie (rare), Black Grouse, Rock Ptarmigan, Willow Ptarmigan (the British subspecies known as Red Grouse, an excellent candidate for a future split and another endemic), the gorgeous Mandarin Duck, the endemic Scottish Crossbill, localized Ring Ouzel, Crested Tit, Horned Grebe, Arctic and Red-throated loon, and raptors such as the striking Red Kite, Eurasian Sparrowhawk, Eurasian Buzzard, and Golden and White-tailed eagle (rare). Most of these breed only within the British Isles, exclusively here in this wild region of Scotland, and we have good chances of seeing most of them. -

Impacts of Climate Change on Woodland Birds; from Individual Behaviour to Population

Impacts of Climate Change on Woodland Birds; From Individual Behaviour to Population Change Thesis submitted in part fulfilment of PhD Jeremy Alexander Smith September 2019 Acknowledgements I would first like to thank my family who have not only supported me through the last four years but for my whole journey to get here. This thesis is dedicated to my mum Penny Smith who has been a rock throughout my life and encouraged me with my decisions even when they have seemed completely impossible or down right stupid. Similar thanks must be given for my supervisors. Dr Rob Thomas has known me since 2006 when he introduced me to Pied Flycatchers, ever since then I haven’t been able to leave them alone and nor the dataset from Cwm Clydach. His continuous pastoral, emotional and supervisory care has been essential to me getting here. I would also like to thank Drs Hefin Jones and Ian Vaughan for all of their personal and professional guidance through the years and the many hours they have spent reading and commenting on chapters. Thanks also go to Dr Sean Rands for his input in the creation of the project, grant application and his help during the project. Although not formally a supervisor, Dr Fred Slater’s assistance throughout the field seasons was invaluable and his kind training of me was exceptionally gratefully received. This thesis would not have been possible without the data so graciously provided by the Gower Ornithological Society and all of the field work conducted by the volunteers over many years, thank you! My particular gratitude to Heather Coats who has been a contact and advisor along the way. -

Common Redstart (Phoenicurus Phoenicurus) Potential Habitat

Common Redstart (Phoenicurus phoenicurus) Areas and status: Largest populations in the uplands of north and west Britain. Now more localised in lowlands, with higher densities around the New Forest, North Midlands and South West England. Sharp population decline in 1960s/70s, largely stable since. BoCC amber list. Woodland type: Upland oak woodland, upland mixed ashwoods, upland birch woodland, wood pasture and parkland, lowland broadleaved, coniferous woodland but preference for broadleaf. Preferred habitat niches: Mature, open-spaced woodland, preference for open oak-birch woods Often on woodland edge adjacent to semi-natural habitat; also in mature scrub on bracken slopes Preference for heavily wooded landscapes and larger woodland blocks of >5ha, although scarce in south-east England Nests in tree holes, often forages in sparsely vegetated field layer Potential habitat management issues associated with decline: ©Mike Langman (rspb-images.com) Loss of older trees especially where woodlands are adjacent to open landscapes such as farmland Succession causing infill/crowding of mature trees and loss of open structure in woodland interior Lack of low-intensity grazing to maintain field layer structure Invasion by holly, beech, rhododendron etc. replacing open structure Agricultural improvement of land adjacent to otherwise suitable woodland edges Potential habitat management solutions: Prescription Comment Establish ability to manage Graze to maintain open character of understorey and to create or preserve areas of bare ground and grazing/browsing sparse vegetation (territories focused on these). Aim for a light understory with open space within it Thinning crowded stands to Selectively thin, retaining >75% canopy to limit understorey regeneration through maintaining shade, encourage tree canopy while encouraging bigger trees by providing space for development. -

Birds of High-Mountain Daghestan, a Report Based on Two Decades Bird Survey

Journal of Wildlife and Biodiversity 4(2): 73-84 (2020) (http://jwb.araku.ac.ir/) Scientific Report DOI: 10.22120/jwb.2020.115601.1098 Birds of High-mountain Daghestan, A report based on two decades bird survey that include representatives of not only High- Evgeny Ev Vilkov mountain, Intra-mountain, and Piedmont Caspian Institute of Biological Resources, Daghestan but also of the plains of the republic. Daghestan Scientific Centre RAS, M. Gadzhiev However, the formation principle and St. 45, Makhachkala, Russia composition of these communities still have to *Email: [email protected] be revealed. Received: 11 October 2019 / Revised: 26 March 2020 / Accepted: The purpose and objectives of the research were 26 March 2020 / Published online: 15 April 2020. Ministry of Sciences, Research, and Technology, Arak University, Iran. to describe specific features of bird ecology for each of the 11 bird communities forming the Abstract avifauna ecological structure of High-mountain The paper is based on 19 years (1998-2017) of Daghestan. the avifauna monitoring in High-mountain Daghestan. Each of 11 bird communities of the The paper summarizes the results of 19–year study area is characterized by its whole set of (1998–2017) ornithological counts carried out in birds, including the rarely occurred species since 13 key sites, located within 6 administrative the latter promotes the formation of a unique districts of High-mountain Daghestan. Material pattern not only of an individual faunal and methods are fully represented in Report 1. community but also the entire avifauna of the To characterize ecologically different species of region. It is assumed that a specific avifauna birds, the author's classification was used pattern of High-mountain Daghestan is (Vilkov 2010b), distinguishing the birds by their determined not only by resident communities of occurrence in preferred habitats that allowed the typical mountain birds but also by nesting in the identification of 11 bird communities (Vilkov mountains adapted populations of migratory 2020, Fig.