(HSRA) Implementation Progress

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TAMBULI APRIL 2006 Issue 2Nd EDIT

Senator Ralph Recto as Chairperson of the Senate Committee on Ways and Means with Senator Juan Ponce Enrile, held recently a public hearing on the proposed Fiscal Incentives Bill and the Anti- Smuggling Bill, which FPI has been vigorously supporting. FPI on Anti-Smuggling and Fiscal Incentives Bills he Federation of Philippine Industries (FPI) presented its T recommendations to the Senate Ways and Means Committee for possible incorporation on the proposed Anti-Smuggling and Fiscal Incentives Bills. Senator Ralph Recto, with Senators Juan Ponce Enrile and Juan Flavier as members tackling the two essential bills, chairs the Senate Committee on Ways and Means during a well-attended public hearing held recently at the Philippine Senate. FPI Recommendations on the Anti-Smuggling Bill: FPI, through its President, Mr. Jesus L. Arranza, recommended the following for possible incorporation on the proposed Anti- FPI President Jesus L. Arranza joined the round table discussions Smuggling Bill: with President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo on various issues of • All Inward Foreign Manifests (IFMs) should be published in national concerns, which was aired, live via NBN Channel 4. the Bureau of Customs and/or in the Department of Trade and Industry’s web sites. President Gloria Macapagal- FPI Legal Team to assist BOC • All Import Declarations should follow the Harmonized System Arroyo approved in principle the of 8-digit heading to prevent misclassification. issuance of an Executive Order, President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo • Every classification by Tariff Heading should have value range requiring all government welcomed the assistance of the and date, which should be published in the BOC and/or DTI agencies and government Federation of Philippine Industries websites and periodically updated. -

Philippinen: Wahlen in Turbulenter Zeit

Willibold Frehner Philippinen: Wahlen in turbulenter Zeit Am 14. Mai 2001 wurden in den Philippinen Wahlen Die Filipinos haben im Januar 2001 ihren unfähigen durchgeführt, die auch als und korrupten Präsidenten Joseph Estrada aus dem Referendum für oder gegen Amt gejagt. Die neue Variante der People’s Power hat die neue Regierung von den auf sechs Jahre gewählten Präsidenten bereits Präsidentin Arroyo angese- hen wurden. Kandidaten für nach 31 Monaten chaotischer Regierung gezwungen, den Kongress, aber auch den Präsidentenpalast zu verlassen. Gegen den frühe- Gouverneure und Bürger- ren Präsidenten Estrada, gegen eine Reihe seiner Ge- meister wurden gewählt. Mitten im Wahlkampf wur- folgsleute und gegen Begünstigte wurden Anklagen de der frühere Präsident wegen Korruption und Veruntreuung vorbereitet. Estrada verhaftet und es Estrada und sein Sohn Jinggoy wurden verhaftet und kam zu massiven Auseinan- in ein eigens für diese beiden Häftlinge eingerichtetes dersetzungen zwischen Poli- zei, Militär und Demonst- Spezialgefängnis gebracht. ranten. Die Emotionen Die neue Präsidentin Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo schlugen hoch und hundert hat von ihrem Vorgänger ein schweres Erbe über- Tote waren zu beklagen. Die nommen. Insbesondere im wirtschaftlichen und im Wahlen unterstrichen, dass das Land derzeit in zwei politischen Bereich zeigen sich gravierende Pro- Lager gespalten ist. Eine bleme, die sich nicht kurzfristig lösen lassen. Mehrheit der Bevölkerung Am 14. Mai 2001 wurden in den Philippinen unterstützt die Regierung, Wahlen durchgeführt, die auch als Referendum für aber eine – wenn auch be- trächtliche – Minderheit oder gegen die neue Regierung der Präsidentin Ar- votierte für das Lager des royo angesehen wurden. Kandidaten für den Senat gestürzten Estrada. Mit den und den Kongress, aber auch Gouverneure und Bür- Wahlergebnissen kann die Regierung politisch überle- germeister wurden gewählt. -

![THE HUMBLE BEGINNINGS of the INQUIRER LIFESTYLE SERIES: FITNESS FASHION with SAMSUNG July 9, 2014 FASHION SHOW]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7828/the-humble-beginnings-of-the-inquirer-lifestyle-series-fitness-fashion-with-samsung-july-9-2014-fashion-show-667828.webp)

THE HUMBLE BEGINNINGS of the INQUIRER LIFESTYLE SERIES: FITNESS FASHION with SAMSUNG July 9, 2014 FASHION SHOW]

1 The Humble Beginnings of “Inquirer Lifestyle Series: Fitness and Fashion with Samsung Show” Contents Presidents of the Republic of the Philippines ................................................................ 8 Vice-Presidents of the Republic of the Philippines ....................................................... 9 Popes .................................................................................................................................. 9 Board Members .............................................................................................................. 15 Inquirer Fitness and Fashion Board ........................................................................... 15 July 1, 2013 - present ............................................................................................... 15 Philippine Daily Inquirer Executives .......................................................................... 16 Fitness.Fashion Show Project Directors ..................................................................... 16 Metro Manila Council................................................................................................. 16 June 30, 2010 to June 30, 2016 .............................................................................. 16 June 30, 2013 to present ........................................................................................ 17 Days to Remember (January 1, AD 1 to June 30, 2013) ........................................... 17 The Philippines under Spain ...................................................................................... -

Papal Visit Philippines 2014 and 2015 2014

This event is dedicated to the Filipino People on the occasion of the five- day pastoral and state visit of Pope Francis here in the Philippines on October 23 to 27, 2014 part of 22- day Asian and Oceanian tour from October 22 to November 13, 2014. Papal Visit Philippines 2014 and 2015 ―Mercy and Compassion‖ a Papal Visit Philippines 2014 and 2015 2014 Contents About the project ............................................................................................... 2 About the Theme of the Apostolic Visit: ‗Mercy and Compassion‘.................................. 4 History of Jesus is Lord Church Worldwide.............................................................................. 6 Executive Branch of the Philippines ....................................................................... 15 Presidents of the Republic of the Philippines ....................................................................... 15 Vice Presidents of the Republic of the Philippines .............................................................. 16 Speaker of the House of Representatives of the Philippines ............................................ 16 Presidents of the Senate of the Philippines .......................................................................... 17 Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of the Philippines ...................................................... 17 Leaders of the Roman Catholic Church ................................................................ 18 Pope (Roman Catholic Bishop of Rome and Worldwide Leader of Roman -

Aligning Healthcare Facilities with KP

www.doh.gov.ph what’s inside Polio Endgame Conference of the EDITORIAL: We’re Message Parties 6 almost there from the Health Secretary p2 p3 p4 p8 VOL. 1 ISSUE 6 OCTOBER 2014 Statement of Acting Health Secretary Janette Aligning healthcare facilities Loreto Garin in the Passing of Secretary Juan with KP Martin Flavier For 2014, HFEP allocates PhP 13.5 B for construction, upgrading of 448 hospitals, QUALITY HEALTHCARE FACILITIES FOR FILIPINOS The development of quality healthcare 1,028 RHU’s facilities, through the Health Facilities Enhancement Program (HFEP), is a vital step in achieving Kalusugan Pangkalahatan. With Health Secretary Enrique Ona at the helm, a more improved quality and 1,365 of life especially in healthcare, is on its way for every Filipinos We are no longer the once BHSs nation- Moreover, these facilities are under 761 LGU PhilHealth enrolment, there are needs to have super-provider of health services. hospitals and other health facilities and 70 DOH health facilities that can respond to their health We are now a servicer of servicers. wide hospitals, 3,395 rural health units (RHUs), and 2,685 care needs at all levels of care,” Sec. Ona said. -Sec. Juan M. Flavier By Gelyka Ruth R. Dumaraos barangay health stations (BHSs). “Through modernization of DOH hospitals in the HFEP for this year funded an amount of PhP 13.5 regions outside NCR, congestion of DOH specialized Dr. Juan Martin Flavier was among THE ACHIEVEMENT of Kalusugan Pangkalahatan billion for the upgrading, rehabilitation, expansion, hospitals in Metro Manila will be reduced,” he added. -

No Pain, No Gain Juan M

26 World Heolth • 48th Year, No. 1, January-February 1995 No pain, no gain Juan M. Flavier aria, a chubby nation, or in the form of and carefree streamers and snacks for Mtwo-year-old, volunteers, and funds for was eagerly awaiting her syringes and vaccines. turn for her patak, her The most important two drops of oral polio support came from the vaccine. She could still frontline health workers. remember how peculiar The vaccinations took the taste was. This is place where people going to be her fourth would usually congre patak. Her Aunt Loleng gate- in schools, was affected by this dis churches, train and bus ease and she goes around stations, airports, piers, with a heavy limp. The waiting-rooms, day-care Or Juan Flavier (second from the left) plays his part in the polio vaccination thought of last month's campaign. centres, shopping malls, scene when some popular restaurants, mu children cried after getting their but today she was trying to be an nicipal and city halls and the houses measles injections made Maria example. "Come on, mother. of vi ll age captains or councillors. somewhat apprehensive. She could Remember, it's just like an ant's bite. One local city mayor even waylaid remember her mother's encourage Remember, no pain, no gain," Maria all incoming provincial buses in ment: "Come on, children. It's all and Clara both said with a laugh. order to persuade the travellers to be right. It 's just like an ant's bite. It's immunized. nothing really. Remember, no pain, The response was overwhelming. -

Art of Nation Building

SINING-BAYAN: ART OF NATION BUILDING Social Artistry Fieldbook to Promote Good Citizenship Values for Prosperity and Integrity PHILIPPINE COPYRIGHT 2009 by the United Nations Development Programme Philippines, Makati City, Philippines, UP National College of Public Administration and Governance, Quezon City and Bagong Lumad Artists Foundation, Inc. Edited by Vicente D. Mariano Editorial Assistant: Maricel T. Fernandez Border Design by Alma Quinto Project Director: Alex B. Brillantes Jr. Resident Social Artist: Joey Ayala Project Coordinator: Pauline S. Bautista Siningbayan Pilot Team: Joey Ayala, Pauline Bautista, Jaku Ayala Production Team: Joey Ayala Pauline Bautista Maricel Fernandez Jaku Ayala Ma. Cristina Aguinaldo Mercedita Miranda Vincent Silarde ALL RIGHTS RESERVED Apart from fair dealing for the purpose of research or review, as permitted under the copyright, this book is subject to the condition that it should not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, sold, or circulated in any form, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher. The scanning, uploading and distribution of this book via the Internet or via other means without the permission of the publisher is illegal and punishable by applied laws. ALL SONGS COPYRIGHT Joey Ayala PRINTED IN THE PHILIPPINES by JAPI Printzone, Corp. Text Set in Garamond ISBN 978 971 94150 1 5 TABLE OF CONTENTS i MESSAGE Mary Ann Fernandez-Mendoza Commissioner, Civil Service Commission ii FOREWORD Bro. Rolando Dizon, FSC Chair, National Congress on Good Citizenship iv PREFACE: Siningbayan: Art of Nation Building Alex B. Brillantes, Jr. Dean, UP-NCPAG vi ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS vii INTRODUCTION Joey Ayala President, Bagong Lumad Artists Foundation Inc.(BLAFI) 1 Musical Reflection: KUNG KAYA MONG ISIPIN Joey Ayala 2 SININGBAYAN Joey Ayala 5 PART I : PAGSASALOOB (CONTEMPLACY) 9 “BUILDING THE GOOD SOCIETY WE WANT” My Hope as a Teacher in Political and Governance Jose V. -

Governance in Health

3 GOVERNANCE IN HEALTH PEDRITA B. DELA CRUZ I. INTRODUCTION A nation's health does not exist in a vacuum. Today, health is no longer seen from a narrow disease-oriented perspective but recognized as both a means and an end of development. This chapter defines health governance as the ability to harness and mobilize resources to fulfill three fundamental goals: (1) improve the health of the population to help achieve productivity or societal goals; (2) respond to people's expectations; and, (3) provide financial protection against the cost of ill-health. The World Health Organization (WHO) identified these goals as concerns that should drive health systems (World Health Report 2000: 8). The term "resources" covers both material and non-material resources. Material resources include financial, human, facilities, equipment and others. These constitute the "oil" that determines the depth and reach of public health programs or campaigns. Non-material resources, on the other hand, include leadership and management, morale and teamwork, confidence, vision and discipline, creativity and openness, values and culture. They are the "glue" that holds the material resources together, and the "energy" that gives governance ethical direction and momentum. They produce or multiply the material resources. They determine whether these resources are harnessed and maximized or go to waste. Material resources alone are not enough to ensure good health outcomes. Sri Lanka, for example, has a relatively low percentage of GDP devoted to health expenditures but has good health status indicators. India, which has a relatively high percentage of GDP for health expenditures, performs poorly, as measured by health indicators (Figure 1). -

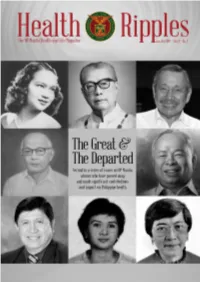

2018 Jan-Jun / Vol. 4 No. 1

The UP Manila Health and Life Magazine i The UP Manila Health Ripples magazine is published bi-annually by the UP Manila Information, Publication, and Public Affairs Office (IPPAO), 8th floor, Philippine General Hospital Central Block, Tel. nos. 554-8400 local 3842. Contributions are welcome. Please email to [email protected] or send to the IPPAO. EDITOR: Cynthia M. Villamor; EDITORIAL CONSULTANT: Dr. Olympia Q. Malanyaon; WRITERS: Cynthia M. Villamor, Fedelynn M. Jemena, January R. Kanindot, Charmaine A. Lingdas; Anne Marie D. Alto LAYOUT ARTIST: Anne Marie D. Alto; PHOTOGRAPHER: Joseph Bautista; CIRCULATION: Sigrid G. Cabiling; Contributing Josephine D. Agapito ii Health Ripples Table of Contents Dr. Florentino B. Herrera, Jr: Humanizing Philippine Medicine 2 Cynthia M. Villamor Dr. Geminiano T. de Ocampo: National Scientist 7 and Father of Modern Philippine Ophthalmology Anne Marie D. Alto Dr. Minda Luz M. Quesada: Passionate Health Champion and Advocate 12 Charmaine A. Lingdas Charlotte A. Floro: Pillar of Rehabilitation Sciences in the Philippines 15 January R. Kanindot Dr. Magdalena C. Cantoria: Advancing Philippine Pharmacy and Botany 19 Fedelynn M. Jemena Dr. Alberto “Quasi” G. Romualdez, Jr.: Crusader for Universal Health Care 22 Charmaine A. Lingdas Dr. Juan M. Flavier: A Doctor for the People 27 Fedelynn M. Jemena Dr. Serafin C. Hilvano: Pillar of Modern Philippine Surgery 32 Cynthia M. Villamor The UP Manila Health and Life Magazine 1 Dr. Florentino B. Herrera, Jr: Humanizing Philippine Medicine By Cynthia M. Villamor “Health must be viewed as both a means to an end and as an end in itself. It is a means insofar as it is a precondition for an individual to harness and maximize his potential as a productive member of the community. -

On Becoming a Medical Road Warrior: a Speech

On Becoming a Medical Road Warrior By Dr. Sibyl Jade Pena Good morning, honorable guests and most especially to the new medical graduates. Thank you 1 for giving me the time and space to share some thoughts with you, and to sum up more than 15 Page years of wandering the world in the spoor of epidemics, disasters and catastrophes, both natural and man-made. First I would like to give homage to a singular doctor who recently passed away. Since I was born and grew up in a family of teachers and writers, the expectation was that I would continue the tradition. While in high school, however, I came upon this singular book, “Doctor to the Barrios,” by Juan Flavier. It was an account of his life as a doctor in the then countryside of Cavite, in the 1950s, at the height of the Huk rebellion. Working with and among peasants, Dr. Flavier found himself hard put upon and compelled to be creative in teaching health concepts to the barrio folks, including family planning. Barrio folks then tended to leave matters of health and children to fate and faith, so Dr. Flavier would run up against peasant wisdom in these matters. Reading Dr. Flavier’s book inspired me to aspire to be a doctor. The stereotype of the urban-based doctor – practicing in sanitized clinics and hospitals, assisted by other medical professionals, dispensing medical wisdom to patients who can pay, earning a ton of money and living a quiet life -- Such a stereotype was the complete anti-thesis of the doctor in Dr. -

Health Devolution, Civil Society Participation and Volunteerism: Political Opportunities and Constraints in the Philippines

Health Devolution, Civil Society Participation and Volunteerism: Political Opportunities and Constraints in the Philippines Maria Ela L. Atienza, Ph.D.1 Paralleling the general decentralization trend in recent decades, health sector decentralization policies have been implemented on a broad scale throughout the developing world since the 1980s. Often in combination with health finance reform, decentralization has been touted as a key means of improving health sector performance and promoting social and economic development. (World Bank 1993) However, some preliminary empirical data indicate that results of health sector decentralization have been mixed, at best (Bossert, Beauvais and Bowser 2000: 1). In the case of the Philippines since 1992, health services began to be devolved under the 1991 Local Government Code (LGC) or Republic Act No. 7160. Some case studies have shown that beyond decentralization reform itself, civil society participation and volunteerism are crucial in improving health service delivery in the Philippines (Atienza 2003 & 2004). Moreover, civil society organizations have been instrumental in enhancing community participation in health service delivery. Non-government organizations (NGOs), people’s organizations (POs) and socio-civic groups have the “capacity to mobilize communities for health-related activities” and social action, “generate resources”, “and organize communities around health and development issues” (Batangan 2006: 105). As shown in several case studies in health service delivery, civil society groups and volunteers in the area of health are in the process of performing some of the democratizing roles mentioned by Diamond (1999: 218-260): effecting transition from clientelism to citizenship at the local level; recruiting and 1 The author is Associate Professor of the Department of Political Science, and Deputy Director of the Third World Studies Center, University of the Philippines, Diliman. -

POPULAR POLITICS of DEMOCRATISATION Philippine Cases in Comparative and Theoretical Perspective

1 Contribution to anthology edited by Mohanty&Murkherji with Törnquist POPULAR POLITICS OF DEMOCRATISATION Philippine Cases in Comparative and Theoretical Perspective Olle Törnquist December 1995* Uppsala University, Dept. of Government-Development Studies Unit; P.O.Box 514, S-751 20 Uppsala, Sweden - Tele +46-(0)18-18 38 04; Fax 18 19 93; e-mail [email protected] _________________________________________________ INTRODUCTION Only a few decades ago, democratisation in South and Southeast Asia was primarily a question of creating the most essential prerequisites in terms of "constituting the demos". Firstly anti-imperialism to establish independent nation states, thus making it possible for people in the former colonies to govern their own countries. Secondly anti-feudalism and basic improvements for the labourers, thus making people autonomous enough to act in accordance with their own interests and ideas. Popular left oriented nationalist and communist movements were in the forefront. By now, however, capitalism is expanding – along with limited forms of democracy – while the predominant political development Project within the Left1 is in shambles. Is a new one emerging? What is the importance of democratisation for renewal- oriented radical movements and organisations? And most important, do they carry the potential of anchoring and broadening democracy in the area – just as popular movements, and especially the more organised labour movement, did during the democratisation of Western Europe? The situation, of course, is very different and varies among the countries. For instance, while the fiscal and institutional base of the state is weakened, surviving rulers and executives re-organise their "fiefdoms" and networks and privatise them further.