Volume XIV Issue 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Review of Generative Adversarial Networks in Cancer Imaging: New Applications, New Solutions

A Review of Generative Adversarial Networks in Cancer Imaging: New Applications, New Solutions Richard Osualaa,∗, Kaisar Kushibara, Lidia Garruchoa, Akis Linardosa, Zuzanna Szafranowskaa, Stefan Kleinb, Ben Glockerc, Oliver Diaza,∗∗, Karim Lekadira,∗∗ aArtificial Intelligence in Medicine Lab (BCN-AIM), Faculty of Mathematics and Computer Science, University of Barcelona, Spain bBiomedical Imaging Group Rotterdam, Department of Radiology & Nuclear Medicine, Erasmus MC, Rotterdam, The Netherlands cBiomedical Image Analysis Group, Department of Computing, Imperial College London, UK Abstract Despite technological and medical advances, the detection, interpretation, and treatment of cancer based on imaging data continue to pose significant challenges. These include high inter-observer variability, difficulty of small-sized le- sion detection, nodule interpretation and malignancy determination, inter- and intra-tumour heterogeneity, class imbal- ance, segmentation inaccuracies, and treatment effect uncertainty. The recent advancements in Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) in computer vision as well as in medical imaging may provide a basis for enhanced capabilities in cancer detection and analysis. In this review, we assess the potential of GANs to address a number of key challenges of cancer imaging, including data scarcity and imbalance, domain and dataset shifts, data access and privacy, data an- notation and quantification, as well as cancer detection, tumour profiling and treatment planning. We provide a critical appraisal of the existing literature of GANs applied to cancer imagery, together with suggestions on future research directions to address these challenges. We analyse and discuss 163 papers that apply adversarial training techniques in the context of cancer imaging and elaborate their methodologies, advantages and limitations. With this work, we strive to bridge the gap between the needs of the clinical cancer imaging community and the current and prospective research on GANs in the artificial intelligence community. -

CBSPD New Certified Members ‐ May 2015 Expiration Date 5/31/2020

Page 1 CBSPD New Certified Members ‐ May 2015 Expiration Date 5/31/2020 [ CERTIFIED IN STERILE PROCESSING MANAGEMENT ] Total Sat for Exam = 24 Total Passed = 18 ( 75% ) Total Failed = 6 ( 25% ) TEST CODE FIRST NAME LAST NAME CITY STATE COUNTRY MGMT Layla Mohamed Al Dhamen Dammam Saudi Arabia MGMT Sagar Bhosale Mumbai India MGMT Virgilio Casinares Riyadh Saudi Arabia MGMT Tiffany Dailey Cranberry PA MGMT Ashly Grantham Concord NH MGMT Charles Hathcoat Hoover AL MGMT Trina Kline Alanson MI MGMT Latif Loveless Rock Hill SC MGMT Narcissus Archimedes Macalintal Jeddah Saudi Arabia MGMT Vijay Mestri Mumbai India MGMT Linda Mosley Birmingham AL MGMT Ernest Nichols East Stroudsburg PA MGMT Brenda Perez Hidalgo TX MGMT Toni Piper Tallahassee FL MGMT Rajendra Shirvalkar Mumbai India MGMT Krystal Westmoreland Chicago IL MGMT Beverly Wilhelm Cottonwood CA MGMT Sanida Zukic Roseville CA [ CERTIFIED SURGICAL INSTRUMENT SPECIALISTS ] Total Sat for Exam = 17 Total Passed = 17 ( 100% ) Total Failed = 0 TEST CODE FIRST NAME LAST NAME CITY STATE COUNTRY SIS Ramzi Ahmed Al-Sultan Saudi Arabia SIS Nicole Anderson Houston TX SIS Bruce Bidwell Redmond OR SIS Lynn Bratzke Janesville WI SIS Malinda Elammari Raleigh NC Page 2 CBSPD New Certified Members ‐ May 2015 Expiration Date 5/31/2020 TEST CODE FIRST NAME LAST NAME CITY STATE COUNTRY SIS Jerome Fabricante Riyadh Saudi Arabia SIS Christopher Franklin Indianapolis IN SIS LaChandra Howell Bahama NC SIS Jasmin Jenkins Cincinnati OH SIS Rodolfo Jorge Sarasota FL SIS Jennifer Martinez Albuquerque NM SIS Amanda McCord -

The Distillers' Charity Auction

The Distillers’ Charity Auction Tuesday 10th April 2018 Mercers’ Hall, Ironmonger Lane, London EC2V 8HE 003_Info_WCD 06/09/2013 15:18 Page 3 A brief history of theT Companyhe D istillers’ Chinvitear leadingity A membersucti ofo then industry to form a The Worshipful Company of Distillers was founded panel discussion. The Gin Guild is dedicated to in 1638 by Royal Charter of Charles I with powers celebrating the heritage of gin, recognising what to regulate the distillingTh tradeursd withinay 1 721t hmiles Oc ofto thebe r 2makes013 great quality gin and the furtherance of the cities of London and Westminster. Our founder was enjoyment of the spirit. an eminent physician,A Sirpo Theodorethecar idees Mayerne.’ Hall, Black Friars Lane, London EC4V 6EJ Education and Charity It was not until 1672 that the Company acquired Scholarships are offered in conjunction with the its Livery, and in 1774H theo sCourtted of b Commony: Bria n MorrWineison and, T hSpirite M Educationaster o fTrust Th eand W Heriot-Wattorshipfu l Company of Distillers Council passed an Act recognising and reinforcing University, with the awards supporting student fees the monopoly of the Distillers’Sir Jac kCompanyie Stew ina thert, OBE or paying for visits to distilleries to further their City. This dominance was short-lived and the practical education. In 2001 the Company initiated Company’s formal role as regulator of, and the development of a Professional Certificate in Auctioneer: David Elswood, Christie’s International Director of Wine spokesman for, the industry gradually fell away Spirits Course by the Wine and Spirit Education as more workable legislation was put in place Trust. -

Illustrated Flora of East Texas Illustrated Flora of East Texas

ILLUSTRATED FLORA OF EAST TEXAS ILLUSTRATED FLORA OF EAST TEXAS IS PUBLISHED WITH THE SUPPORT OF: MAJOR BENEFACTORS: DAVID GIBSON AND WILL CRENSHAW DISCOVERY FUND U.S. FISH AND WILDLIFE FOUNDATION (NATIONAL PARK SERVICE, USDA FOREST SERVICE) TEXAS PARKS AND WILDLIFE DEPARTMENT SCOTT AND STUART GENTLING BENEFACTORS: NEW DOROTHEA L. LEONHARDT FOUNDATION (ANDREA C. HARKINS) TEMPLE-INLAND FOUNDATION SUMMERLEE FOUNDATION AMON G. CARTER FOUNDATION ROBERT J. O’KENNON PEG & BEN KEITH DORA & GORDON SYLVESTER DAVID & SUE NIVENS NATIVE PLANT SOCIETY OF TEXAS DAVID & MARGARET BAMBERGER GORDON MAY & KAREN WILLIAMSON JACOB & TERESE HERSHEY FOUNDATION INSTITUTIONAL SUPPORT: AUSTIN COLLEGE BOTANICAL RESEARCH INSTITUTE OF TEXAS SID RICHARDSON CAREER DEVELOPMENT FUND OF AUSTIN COLLEGE II OTHER CONTRIBUTORS: ALLDREDGE, LINDA & JACK HOLLEMAN, W.B. PETRUS, ELAINE J. BATTERBAE, SUSAN ROBERTS HOLT, JEAN & DUNCAN PRITCHETT, MARY H. BECK, NELL HUBER, MARY MAUD PRICE, DIANE BECKELMAN, SARA HUDSON, JIM & YONIE PRUESS, WARREN W. BENDER, LYNNE HULTMARK, GORDON & SARAH ROACH, ELIZABETH M. & ALLEN BIBB, NATHAN & BETTIE HUSTON, MELIA ROEBUCK, RICK & VICKI BOSWORTH, TONY JACOBS, BONNIE & LOUIS ROGNLIE, GLORIA & ERIC BOTTONE, LAURA BURKS JAMES, ROI & DEANNA ROUSH, LUCY BROWN, LARRY E. JEFFORDS, RUSSELL M. ROWE, BRIAN BRUSER, III, MR. & MRS. HENRY JOHN, SUE & PHIL ROZELL, JIMMY BURT, HELEN W. JONES, MARY LOU SANDLIN, MIKE CAMPBELL, KATHERINE & CHARLES KAHLE, GAIL SANDLIN, MR. & MRS. WILLIAM CARR, WILLIAM R. KARGES, JOANN SATTERWHITE, BEN CLARY, KAREN KEITH, ELIZABETH & ERIC SCHOENFELD, CARL COCHRAN, JOYCE LANEY, ELEANOR W. SCHULTZE, BETTY DAHLBERG, WALTER G. LAUGHLIN, DR. JAMES E. SCHULZE, PETER & HELEN DALLAS CHAPTER-NPSOT LECHE, BEVERLY SENNHAUSER, KELLY S. DAMEWOOD, LOGAN & ELEANOR LEWIS, PATRICIA SERLING, STEVEN DAMUTH, STEVEN LIGGIO, JOE SHANNON, LEILA HOUSEMAN DAVIS, ELLEN D. -

Masons' Material

! ' P . LOCAL NEWS. Best and Worst, “he Olneyville Times “Is this the best wurst you can send & Miss Annle O'Connel!l has taken & po me?" asked the lady who walked into STANTON FARNUM (8 PUBLISHED Al sition with the Providence Gas Co. the meat store with a package of that ARTISIIC WORKERS IN Oloeywille Olneyville, R. 1.. edible in her hand, Square, Rhode Island pensions: Widows “Madam,” answered the meat man, Mvery Friday “it 1s the best wurst we have.” Cranite and Marble. minors, etc. Mary B. Straght. Riverpolnt, “Well, 1t Is the worst [ ever RST~ TYLMKLN XL D G s ss. wurst A large assortment of Monuments and Tablets constantly en hand, Sulesstption Price §l.OO Por Yoear. saw.® ; Plumbers' Slabs, Decoratlons, am sorry to hear Interier Marble etc Advertiomg Rates Sest on Application. Club s making arrange. “1 that. The best Original deslgns The Falka I can do is te.try and send you some and estimates furnished upon application, Sibley, Publisher. tor a banguet, which will lake Inspection 4. F. Editor and mente better wurst froem today's lot; but, as | sollcited. Telephone connection. place early rext mon'h, =X sald, that Is the best wurst we have SALESROOM, MASONS’ e ELECTRIC MILL AND MATERIAL -red ot s Seconn at present. | am sure, however, that Q.W George Farnell has boen appointed ad. the wurst we are now making will not - . estate of the late Street, Providence, R. ministrator of the be any worse than this, and it ought to 143 Westminster For New FRIDAY, DECEMBER 12, 1002 Edward Jackman, be better. -

VOTED BEST MARINA 2017 Comments from the Commodore

MAY - AUGUST 2019 HOME TO THE TAHOE YACHT CLUB VOTED BEST MARINA 2017 Comments from the Commodore ell, it appears that Winter is not quite Gastelum holds down the bar on Sundays. We Wfinished in Tahoe. Skiing at Easter is are bringing on additional staff for the summer pretty rare, but we had it this year–we even to make sure the Club runs smoothly. Summer had some fresh snow on Easter Sunday. With hours begin Memorial Day weekend and the the record snowfall, it appears that we will still Clubhouse will be open every day. be skiing on the Fourth of July! I just returned Summer brings the Over-the-Bottom series from a day of skiing. Now to finish planning for power boaters. The kick off party is June 14 for the rest of our summer calendar of events. with the first on the water event on Saturday, It looks like we will soon be turning in the June 15. The Trans Tahoe sailing race is June snow shovels and ski boots for paddle boards 21-22. The annual Concours d’Elegance will and flip-flops. be held August 9-10 back again at the Obexer’s Looking back on a fun filled winter at the Marina. Tahoe Yacht Club, I remember just how much The Tahoe Yacht Club is continuing to sup- we enjoyed a wide range of events. Karaoke port the Tahoe City Commons Beach Concert Night was a huge success–our members have Margaret Holiday series. We will have a booth at the June 30 tremendous enthusiasm and matching amounts concert. -

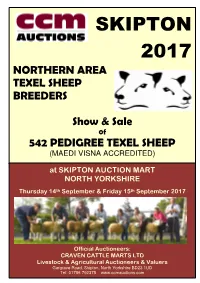

Skipton 2017

SKIPTON 2017 NORTHERN AREA TEXEL SHEEP BREEDERS Show & Sale 0f 542 PEDIGREE TEXEL SHEEP (MAEDI VISNA ACCREDITED) at SKIPTON AUCTION MART NORTH YORKSHIRE th th Thursday 14 September & Friday 15 September 2017 Official Auctioneers: CRAVEN CATTLE MARTS LTD Livestock & Agricultural Auctioneers & Valuers Gargrave Road, Skipton, North Yorkshire BD23 1UD Tel: 01756 792375 www.ccmauctions.com Date received……………………… Number [ ] Northern Area Texel Sheep Breeders’ Club Membership Application Form The Committee of the NATSB has agreed to keep a waiting list of prospective members who reside outside the club area, and therefore are not eligible for automatic membership. If you live OUTSIDE the Club postal code areas, which are: NE/ SR/ DH/ DL/ TS/ BD/ HG/ YO/ LS/ HU/ HD/ HX/ WF/ DN you may apply to be placed onto the waiting list. Please note: 1. No application is guaranteed membership status either now or in the future. 2. Applications will only be accepted on this form. No phone, fax or email applications. 3. Applications will be placed in strict order of receipt onto a waiting list. NAME……………………………………………………………………… ADDRESS………………………………………………………………… ……………………………………………………………………………… ……………………………………………………………………………… POSTCODE………………………….... TEL(inc.STD)………………..………… SIGNED………………………………………………………… Please tear out the form, complete and return by post to the Secretary: c/o Pear Tree Farm, Battersby, Gt. Ayton, North Yorkshire TS9 6LU NORTHERN AREA TEXEL SHEEP BREEDERS TEXEL SALE 2017 PROGRAMME THURSDAY 14th SEPTEMBER INSPECTION (ALL SHEEP) STRICTLY 9.30am – 12.00noon -

Beverage Menu

White Glass Bottle ERNIE ELS BIG EASY WHITE 58 228 Light, semi dry and buttery sensation, great hints of sweet tropical fruit ERNIE ELS SAUVIGNON BLANC 268 Dry, fruit driven white wine with decent layers of acidity Red ERNIE ELS BIG EASY RED 58 228 Light spice, semi dry with a blend of ERNIE ELS MERLOT 388 Dry medium body with hints of plum and dark chocolate ERNIE ELS CABERNET SAUVIGNON 428 Dry minerality with hints of vanilla and great tannins Champagne and Sparkling Wine MOËT & CHANDON BRUT IMPÉRIAL 580 CHEVALIER CHARDONNAY BRUT NV 380 House Pouring Wine JACOB’S CREEK CHARDONNAY 32 168 JACOB’S CREEK MERLOT 32 168 Els Collection from Stellenbosch It all started in 1999 when Ernie Els and the award winning winemaker, Louis Strydom started to develop Ernie Els Wines. With consistent dedication and perseverance, the collection has won numerous awards and has become a wine loved by many. As some say – all dreams man seeks for perfection. We trust that you will enjoy a hint of perfection when sampling from the Els collection. All prices are in Ringgit Malaysia and subject to 6% SST and 10% Service Charge White Wine Glass Bottle SAUVIGNON BLANC, CLOUDY BAY 348 New Zealand VINO CONO SUR TOCORNAL CHARDONNAY 182 Chilean LE CHALLENGE BLANC 182 France TRAPICHE ASTICA TORRONTÉS 182 Argentina Red Wine SHIRAZ, REDVALE 188 Australia FALCONHEAD HAWKERS BAY MERLOT/CABERNET 208 New Zealand MALBEC, TRAPICHE 178 Argentina Spirit All standard Measures are 30 ml APÉRITIF 25 Campari • Martini (Dry, Bianco, Rosso) Bourbon JACK DANIEL’S 28 328 Whisky JOHNNIE -

Interpretations of Fear and Anxiety in Gothic-Postmodern Fiction: an Analysis of the Secret History by Donna Tartt

Cleveland State University EngagedScholarship@CSU ETD Archive 2013 Interpretations of Fear and Anxiety in Gothic-Postmodern Fiction: an Analysis of the Secret History by Donna Tartt Stacey A. Litzler Cleveland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/etdarchive Part of the English Language and Literature Commons How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! Recommended Citation Litzler, Stacey A., "Interpretations of Fear and Anxiety in Gothic-Postmodern Fiction: an Analysis of the Secret History by Donna Tartt" (2013). ETD Archive. 842. https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/etdarchive/842 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by EngagedScholarship@CSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in ETD Archive by an authorized administrator of EngagedScholarship@CSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INTERPRETATIONS OF FEAR AND ANXIETY IN GOTHIC-POSTMODERN FICTION: AN ANALYSIS OF THE SECRET HISTORY BY DONNA TARTT STACEY A. LITZLER Bachelor of Science in Business Indiana University May 1989 Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS IN ENGLISH Cleveland State University December 2013 We hereby approve this thesis of STACEY A. LITZLER Candidate for the Master of Arts in English degree for the Department of ENGLISH and the CLEVELAND STATE UNIVERSITY College of Graduate Studies. _________________________________________________________________ Thesis Chairperson, Dr. Frederick Karem _____________________________________________ -

January 30, 2019 the Honorable Betsy Devos Secretary Department

January 30, 2019 The Honorable Betsy DeVos Secretary Department of Education 400 Maryland Avenue Washington, DC 20202 via electronic submission Re: Docket No. ED-2018-OCR-0064, RIN 1870-AA14, Nondiscrimination on the Basis of Sex in Education Programs or Activities Receiving Federal Financial Assistance Dear Secretary DeVos: Title IX is essential to ensuring that our schools are free from discrimination, including sexual harassment and violence. But the Department of Education’s proposed changes would weaken students’ Title IX protections by narrowing the definition of sexual harassment to potentially exclude much of the abuse students experience and by limiting when schools will respond to reports of sexual harassment and violence. In addition, the rule would put in place school processes that make it harder for students to come forward and receive the support they need when they experience sexual harassment or assault. These changes would ultimately make our schools less safe. As Secretary of Education, you have the power to address this critical civil rights issue and help make schools safer and more equitable for all students. I join with the American Association of University Women (AAUW) in urging you to withdraw the Notice of Proposed Rulemaking on Title IX and to work to ensure schools protect students from sex discrimination by fully enforcing, not rolling back, Title IX’s protections. Signed, Dr. Rachel B. Aarons Las Encinas Road Santa Barbara, CA 93101 Marilyn Abariotes 2222 Jackson St. Blair, NE 68008 Alexandra Abel 17014 Berendo Ave Unit C Gardena, CA 90247 Ms. Olga Abella 12129 N 675th St Robinson, IL 62454 Ms. -

Fire Hits Daphne Recycling Program the Fairhope Police De- Introduces Partment Celebrated Break- Fast with Santa on Dec

BALDWIN LIVING: Fairhope Christmas Parade, PAGE 5 ADCNR Officers help spread Christmas cheer at Academy The Courier PAGE 11 INSIDE DECEMBER 18, 2019 | GulfCoastNewsToday.com | 75¢ Fairhope names public school commissioners Fairhope postpones action on rezoning issues The new Fairhope Public School Commission is in By GUY BUSBY Unit Development. place and ready to take [email protected] That vote was postponed office in January, city of- after Hunter Simmons, city ficials said. The Fairhope FAIRHOPE — Residents planning and zoning manager, City Council voted Dec. 9 to and officials will have to wait said changes to the ordinance name the nine commission until early 2020 for action on a would require new public members. Turn to page 2 to plan to rezone about 38 acres notices be advertised on the read more. as a Planned Unit Develop- proposal. ment at Bay Meadows Avenue “We had some changes on and Alabama 181. that. It's going to have to be The Fairhope City Council readvertised,” Simmons said. had been scheduled to vote “That is current scheduled to GUY BUSBY / STAFF PHOTO Dec. 9 on a proposal to rezone appear back on the agenda on The vote on a Planned Unit Development near Bay Meadows Drive a parcel near the intersec- Jan. 13.” and Alabama 181 has been rescheduled for January. The Fairhope City tion of Alabama 181 and Bay Council had been scheduled to vote Dec. 9 on a proposal to build a Meadows Drive as a Planned SEE REZONING, PAGE 2 development on the site now zoned for agriculture. Fairhope Breakfast with Santa Fire hits Daphne recycling program The Fairhope Police De- introduces partment celebrated Break- fast with Santa on Dec. -

BOCA RATON NEWS Vol

BDI L673 SI AUQ-JZIlaZ FLA 32054 BOCA RATON NEWS Vol. 12, No. 155 Thursday, November 16, 1967 26 Pages Corps pledges water for conservation area Park?Lox' get equal treatment By JIM RIFENBURG BELLE GLADE - Loxahatch- ee, the vast Everglades area west of Boca Raton, will re- ceive as much water as anyone else, including Everglades Na- tional Park, the Corps of En- gineers said here yesterday. More than 250 people attended a public hearing at which the Corps explained plans they hope to put through U.S. Congress for revamping Florida's water- sheds. Preliminary reports had in- dicated Conservation Area number one, known here as.the- Loxahatchee, Area Two and Area Three would be dry 20 times in the next 36 years. Prince Andei Lobanow-Rostovsky, Professor Emeritus, Univer- However, Ted Hauessner, chief of the Corps* Hydrology sity of Michigan and Professor Samua! A. Portnoy, chairman of the Branch, said the preliminary History Department, College of Humanities, Florida Atlantic Uni- reports were not entirely true. versity discuss Russian history prior to lecture by Rostoveky at 'Minimum levels in the Con- FAU this week. The history department was host for the lecture by servation Areas may be low- Prince -- his topic was "50 Years of Soviet Communism: An His- ered from six inches to one torian's Evaluation." Prince Rostovsk is a direct decent of the Florida Atlantic University President Kenneth tion director, and other chamber members after foot, but not more than that," Rurik line, founders of Russia, a former captain of the Russian R. Williams shakes hands with Lester E.