Sverdrup Balance, Western Boundary Currents) Lynne Talley, Fall, 2008

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fronts in the World Ocean's Large Marine Ecosystems. ICES CM 2007

- 1 - This paper can be freely cited without prior reference to the authors International Council ICES CM 2007/D:21 for the Exploration Theme Session D: Comparative Marine Ecosystem of the Sea (ICES) Structure and Function: Descriptors and Characteristics Fronts in the World Ocean’s Large Marine Ecosystems Igor M. Belkin and Peter C. Cornillon Abstract. Oceanic fronts shape marine ecosystems; therefore front mapping and characterization is one of the most important aspects of physical oceanography. Here we report on the first effort to map and describe all major fronts in the World Ocean’s Large Marine Ecosystems (LMEs). Apart from a geographical review, these fronts are classified according to their origin and physical mechanisms that maintain them. This first-ever zero-order pattern of the LME fronts is based on a unique global frontal data base assembled at the University of Rhode Island. Thermal fronts were automatically derived from 12 years (1985-1996) of twice-daily satellite 9-km resolution global AVHRR SST fields with the Cayula-Cornillon front detection algorithm. These frontal maps serve as guidance in using hydrographic data to explore subsurface thermohaline fronts, whose surface thermal signatures have been mapped from space. Our most recent study of chlorophyll fronts in the Northwest Atlantic from high-resolution 1-km data (Belkin and O’Reilly, 2007) revealed a close spatial association between chlorophyll fronts and SST fronts, suggesting causative links between these two types of fronts. Keywords: Fronts; Large Marine Ecosystems; World Ocean; sea surface temperature. Igor M. Belkin: Graduate School of Oceanography, University of Rhode Island, 215 South Ferry Road, Narragansett, Rhode Island 02882, USA [tel.: +1 401 874 6533, fax: +1 874 6728, email: [email protected]]. -

The Decadal Mean Ocean Circulation and Sverdrup Balance

Journal of Marine Research, 69, 417–434, 2011 The decadal mean ocean circulation and Sverdrup balance by Carl Wunsch1 ABSTRACT Elementary Sverdrup balance is tested in the context of the time-average of a 16-year duration time-varying ocean circulation estimate employing the great majority of global-scale data available between 1992 and 2007. The time-average circulation exhibits all of the conventional major features as depicted both through its absolute surface topography and vertically integrated transport stream function. Important small-scale features of the time average only become apparent, however, in the time-average vertical velocity, whether near the surface or in the abyss. In testing Sverdrup balance, the requirement is made that there should be a mid-water column depth where the magnitude of the vertical velocity is less than 10−8 m/s (about 0.3 m/year displacement). The requirement is not met in the Southern Ocean or high northern latitudes. Over much of the subtropical and lower latitude ocean, Sverdrup balance appears to provide a quantitatively useful estimate of the meridional transport (about 40% of the oceanic area). Application to computing the zonal component, by integration from the eastern boundary is, however, precluded in many places by failure of the local balances close to the coasts. Failure of Sverdrup balance at high northern latitudes is consistent with the expected much longer time to achieve dynamic equilibrium there, and the action of other forces, and has important consequences for ongoing ocean monitoring efforts. 1. Introduction The very elegant and powerful theories of the time-mean ocean circulation, treated as a laminar flow, remain of intense interest, despite the widespread recognition that the oceanic kinetic energy is dominated by the time variability. -

(Potential) Vorticity: the Swirling Motion of Geophysical Fluids

(Potential) vorticity: the swirling motion of geophysical fluids Vortices occur abundantly in both atmosphere and oceans and on all scales. The leaves, chasing each other in autumn, are driven by vortices. The wake of boats and brides form strings of vortices in the water. On the global scale we all know the rotating nature of tropical cyclones and depressions in the atmosphere, and the gyres constituting the large-scale wind driven ocean circulation. To understand the role of vortices in geophysical fluids, vorticity and, in particular, potential vorticity are key quantities of the flow. In a 3D flow, vorticity is a 3D vector field with as complicated dynamics as the flow itself. In this lecture, we focus on 2D flow, so that vorticity reduces to a scalar field. More importantly, after including Earth rotation a fairly simple equation for planar geostrophic fluids arises which can explain many characteristics of the atmosphere and ocean circulation. In the lecture, we first will derive the vorticity equation and discuss the various terms. Next, we define the various vorticity related quantities: relative, planetary, absolute and potential vorticity. Using the shallow water equations, we derive the potential vorticity equation. In the final part of the lecture we discuss several applications of this equation of geophysical vortices and geophysical flow. The preparation material includes - Lecture slides - Chapter 12 of Stewart (http://www.colorado.edu/oclab/sites/default/files/attached- files/stewart_textbook.pdf), of which only sections 12.1-12.3 are discussed today. Willem Jan van de Berg Chapter 12 Vorticity in the Ocean Most of the fluid flows with which we are familiar, from bathtubs to swimming pools, are not rotating, or they are rotating so slowly that rotation is not im- portant except maybe at the drain of a bathtub as water is let out. -

![Arxiv:1809.01376V1 [Astro-Ph.EP] 5 Sep 2018](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1996/arxiv-1809-01376v1-astro-ph-ep-5-sep-2018-591996.webp)

Arxiv:1809.01376V1 [Astro-Ph.EP] 5 Sep 2018

Draft version March 9, 2021 Typeset using LATEX preprint2 style in AASTeX61 IDEALIZED WIND-DRIVEN OCEAN CIRCULATIONS ON EXOPLANETS Weiwen Ji,1 Ru Chen,2 and Jun Yang1 1Department of Atmospheric and Oceanic Sciences, School of Physics, Peking University, 100871, Beijing, China 2University of California, 92521, Los Angeles, USA ABSTRACT Motivated by the important role of the ocean in the Earth climate system, here we investigate possible scenarios of ocean circulations on exoplanets using a one-layer shallow water ocean model. Specifically, we investigate how planetary rotation rate, wind stress, fluid eddy viscosity and land structure (a closed basin vs. a reentrant channel) influence the pattern and strength of wind-driven ocean circulations. The meridional variation of the Coriolis force, arising from planetary rotation and the spheric shape of the planets, induces the western intensification of ocean circulations. Our simulations confirm that in a closed basin, changes of other factors contribute to only enhancing or weakening the ocean circulations (e.g., as wind stress decreases or fluid eddy viscosity increases, the ocean circulations weaken, and vice versa). In a reentrant channel, just as the Southern Ocean region on the Earth, the ocean pattern is characterized by zonal flows. In the quasi-linear case, the sensitivity of ocean circulations characteristics to these parameters is also interpreted using simple analytical models. This study is the preliminary step for exploring the possible ocean circulations on exoplanets, future work with multi-layer ocean models and fully coupled ocean-atmosphere models are required for studying exoplanetary climates. Keywords: astrobiology | planets and satellites: oceans | planets and satellites: terrestrial planets arXiv:1809.01376v1 [astro-ph.EP] 5 Sep 2018 Corresponding author: Jun Yang [email protected] 2 Ji, Chen and Yang 1. -

The Gulf Stream (Western Boundary Current)

Classic CZCS Scenes Chapter 6: The Gulf Stream (Western Boundary Current) The Caribbean Sea and the Gulf of Mexico are the source of what is likely the most well- known current in the oceans—the Gulf Stream. The warm waters of the Gulf Stream can be observed using several different types of remote sensors, including sensors of ocean color (CZCS), sea surface temperature, and altimetry. Images of the Gulf Stream taken by the CZCS, one of which is shown here, are both striking and familiar. CZCS image of the Gulf Stream and northeastern coast of the United States. Several large Gulf Stream warm core rings are visible in this image, as are higher productivity areas near the Chesapeake and Delaware Bays. To the northeast, part of the Grand Banks region near Nova Scotia is visible. Despite the high productivity of this region, overfishing caused the total collapse of the Grand Banks cod fishery in the early 1990s. The Gulf Stream is a western boundary current, indicating that if flows along the west side of a major ocean basin (in this case the North Atlantic Ocean). The corresponding current in the Pacific Ocean is called the Kuroshio, which flows north to about the center of the Japanese archipelago and then turns eastward into the central Pacific basin. In the Southern Hemisphere, the most noteworthy western boundary current is the Agulhas Current in the Indian Ocean. Note that the Agulhas flows southward instead of northward like the Gulf Stream and the Kuroshio. Western boundary currents result from the interaction of ocean basin topography, the general direction of the prevailing winds, and the general motion of oceanic waters induced by Earth's rotation. -

Geophysical Fluid Dynamics, Nonautonomous Dynamical Systems, and the Climate Sciences

Geophysical Fluid Dynamics, Nonautonomous Dynamical Systems, and the Climate Sciences Michael Ghil and Eric Simonnet Abstract This contribution introduces the dynamics of shallow and rotating flows that characterizes large-scale motions of the atmosphere and oceans. It then focuses on an important aspect of climate dynamics on interannual and interdecadal scales, namely the wind-driven ocean circulation. Studying the variability of this circulation and slow changes therein is treated as an application of the theory of nonautonomous dynamical systems. The contribution concludes by discussing the relevance of these mathematical concepts and methods for the highly topical issues of climate change and climate sensitivity. Michael Ghil Ecole Normale Superieure´ and PSL Research University, Paris, FRANCE, and University of California, Los Angeles, USA, e-mail: [email protected] Eric Simonnet Institut de Physique de Nice, CNRS & Universite´ Coteˆ d’Azur, Nice Sophia-Antipolis, FRANCE, e-mail: [email protected] 1 Chapter 1 Effects of Rotation The first two chapters of this contribution are dedicated to an introductory review of the effects of rotation and shallowness om large-scale planetary flows. The theory of such flows is commonly designated as geophysical fluid dynamics (GFD), and it applies to both atmospheric and oceanic flows, on Earth as well as on other planets. GFD is now covered, at various levels and to various extents, by several books [36, 60, 72, 107, 120, 134, 164]. The virtue, if any, of this presentation is its brevity and, hopefully, clarity. It fol- lows most closely, and updates, Chapters 1 and 2 in [60]. The intended audience in- cludes the increasing number of mathematicians, physicists and statisticians that are becoming interested in the climate sciences, as well as climate scientists from less traditional areas — such as ecology, glaciology, hydrology, and remote sensing — who wish to acquaint themselves with the large-scale dynamics of the atmosphere and oceans. -

Physical Oceanography - UNAM, Mexico Lecture 3: the Wind-Driven Oceanic Circulation

Physical Oceanography - UNAM, Mexico Lecture 3: The Wind-Driven Oceanic Circulation Robin Waldman October 17th 2018 A first taste... Many large-scale circulation features are wind-forced ! Outline The Ekman currents and Sverdrup balance The western intensification of gyres The Southern Ocean circulation The Tropical circulation Outline The Ekman currents and Sverdrup balance The western intensification of gyres The Southern Ocean circulation The Tropical circulation Ekman currents Introduction : I First quantitative theory relating the winds and ocean circulation. I Can be deduced by applying a dimensional analysis to the horizontal momentum equations within the surface layer. The resulting balance is geostrophic plus Ekman : I geostrophic : Coriolis and pressure force I Ekman : Coriolis and vertical turbulent momentum fluxes modelled as diffusivities. Ekman currents Ekman’s hypotheses : I The ocean is infinitely large and wide, so that interactions with topography can be neglected ; ¶uh I It has reached a steady state, so that the Eulerian derivative ¶t = 0 ; I It is homogeneous horizontally, so that (uh:r)uh = 0, ¶uh rh:(khurh)uh = 0 and by continuity w = 0 hence w ¶z = 0 ; I Its density is constant, which has the same consequence as the Boussinesq hypotheses for the horizontal momentum equations ; I The vertical eddy diffusivity kzu is constant. ¶ 2u f k × u = k E E zu ¶z2 that is : k ¶ 2v u = zu E E f ¶z2 k ¶ 2u v = − zu E E f ¶z2 Ekman currents Ekman balance : k ¶ 2v u = zu E E f ¶z2 k ¶ 2u v = − zu E E f ¶z2 Ekman currents Ekman balance : ¶ 2u f k × u = k E E zu ¶z2 that is : Ekman currents Ekman balance : ¶ 2u f k × u = k E E zu ¶z2 that is : k ¶ 2v u = zu E E f ¶z2 k ¶ 2u v = − zu E E f ¶z2 ¶uh τ = r0kzu ¶z 0 with τ the surface wind stress. -

Evaluation of Subtropical North Atlantic Ocean Circulation in CMIP5 Models Against the Observational Array at 26.5°N and Its Changes Under Continued Warming

1DECEMBER 2018 B E A D L I N G E T A L . 9697 Evaluation of Subtropical North Atlantic Ocean Circulation in CMIP5 Models against the Observational Array at 26.5°N and Its Changes under Continued Warming R. L. BEADLING,J.L.RUSSELL,R.J.STOUFFER, AND P. J. GOODMAN Department of Geosciences, The University of Arizona, Tucson, Arizona (Manuscript received 12 December 2017, in final form 16 September 2018) ABSTRACT Observationally based metrics derived from the Rapid Climate Change (RAPID) array are used to assess the large-scale ocean circulation in the subtropical North Atlantic simulated in a suite of fully coupled climate models that contributed to phase 5 of the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project (CMIP5). The modeled circulation at 26.58N is decomposed into four components similar to those RAPID observes to estimate the Atlantic meridional overturning circulation (AMOC): the northward-flowing western boundary current (WBC), the southward transport in the upper midocean, the near-surface Ekman transport, and the south- ward deep ocean transport. The decadal-mean AMOC and the transports associated with its flow are captured well by CMIP5 models at the start of the twenty-first century. By the end of the century, under representative concentration pathway 8.5 (RCP8.5), averaged across models, the northward transport of waters in the upper 2 WBC is projected to weaken by 7.6 Sv (1 Sv [ 106 m3 s 1; 221%). This reduced northward flow is a combined result of a reduction in the subtropical gyre return flow in the upper ocean (22.9 Sv; 212%) and a weakened net southward transport in the deep ocean (24.4 Sv; 228%) corresponding to the weakened AMOC. -

CIÊNCIAS DO MAR: Dos Oceanos Do Mundo Ao Nordeste Do Brasil

| 1 CIÊNCIAS DO MAR: dos oceanos do mundo ao Nordeste do Brasil Volume 1 Oceano, Clima, Ambientes e Conservação Danielle de Lima Viana Jorge Eduardo Lins Oliveira Fábio Hissa Vieira Hazin Marco Antonio Carvalho de Souza Recife, 2021 Via Design Publicações 2 | Ciências do Mar: dos oceanos do mundo ao Nordeste do Brasil Editores Parecer e revisão por pares Luis Henrique Poersch Danielle de Lima Viana Os textos que compõem essa obra foram Universidade Federal do Rio Grande Doutora em Oceanografia na submetidos à avaliação de um Conselho Revisor, Marcelo Roberto Souto de Melo Universidade Federal de Pernambuco bem como revisados por pares, sendo indicados Universidade de São Paulo para publicação. Pesquisadora do Departamento de Pesca Paulo Guilherme Vasconcelos de Oliveira e Aquicultura da Universidade Federal Universidade Federal Rural de Pernambuco Rural de Pernambuco Conselho revisor [email protected] Danielle de Lima Viana Pollyana Christine Gomes Roque Universidade Federal Rural de Pernambuco Universidade Federal Rural de Pernambuco Jorge Eduardo Lins Oliveira David Mendes Roberto Fioravanti Carelli Fontes Doutor em Biologia Marinha na Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte Universidade Estadual Paulista Université Marie et Pierre Curie Ronaldo Olivera Cavalli -Paris 6-França Fábio Hissa Vieira Hazin Universidade Federal Rural de Pernambuco Universidade Federal do Rio Grande Professor Titular do Departamento de Oceanografia e Limnologia da Fabrício Berton Zanchi Sérgio de Magalhães Rezende Universidade Federal do Rio Grande Universidade -

Seasonal to Interannual Variations of the Western Boundary Current of The

JOURNAL OF GEOPHYSICAL RESEARCH, VOL. 111, C04013, doi:10.1029/2005JC003080, 2006 Seasonal to interannual variations of the western boundary current of the subarctic North Pacific by a combination of the altimeter and tide gauge sea levels Osamu Isoguchi1 and Hiroshi Kawamura1 Received 31 May 2005; revised 30 November 2005; accepted 20 January 2006; published 28 April 2006. [1] Seasonal to interannual variations of the East Kamchatka Current (EKC) and the Oyashio are examined by focusing on their barotropic response to wind forcing by a combined use of altimeter-derived and tide gauge sea levels. An empirical orthogonal function (EOF) analysis is performed on the 9-year altimeter sea level maps with thermosteric signals removed. A second EOF (EOF2) shows a spin-up and spin-down of the subarctic gyres, and its temporal variation is almost accounted for by the time- dependent Sverdrup balance. Tide gauge sea levels at Petropavlovsk-Kamchatsky (PK) agree with EOF2 and the Sverdrup transports in terms of not only the seasonal variation but also its year-to-year variability in winter when the subarctic gyre is spun up most. We also detect two types of EKC/Oyashio variations from the altimeter data: drifting velocities of sea level disturbances and geostrophic velocity anomalies. These two EKC/ Oyashio temporal variations are also accounted for by the Sverdrup balance and agree with the PK sea levels and EOF2. The results imply that the PK sea levels can be a good representative of the subarctic gyre and EKC/Oyashio variations. On the basis of this relation, interannual variations during winter are discussed. -

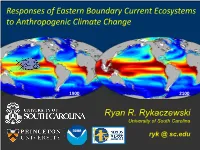

Responses of Eastern Boundary Current Ecosystems to Anthropogenic Climate Change

Responses of Eastern Boundary Current Ecosystems to Anthropogenic Climate Change 1900 2100 Ryan R. Rykaczewski University of South Carolina ryk @ sc.edu We are united by an interest in understanding ecosystem dynamics in the North Pacific Tokyo Columbia ~35,000 students (~300 students in Marine Sciences, with 13 faculty members) John Steven Julia me Riley Viki Connor Sarah Brian Tricia Q: What sorts of scientific topics do we study in my group? A: We want to understand why abundances of fish go up and down. Why is it that fish populations are so abundant (and lucrative to exploit!) during some years and absent during others? How do changes in large-scale physical processes influence… …the structure of the marine ecosystems—species composition and size distribution of the plankton, inter and intra-specific interactions, trophic transfer efficiency… …and affect the world’s marine fish stocks? Variability in eastern boundary current upwelling systems California Canary Current Current Humboldt Benguela Current Current Variability in eastern boundary current upwelling systems oceanic high continental pressure low pressure understand the dynamics of Long-term goal: upwelling ecosystems Upwelling systems: - support highly productive food webs and sustain fisheries critical to the world’s food supply. - may play a role in large-scale climate processes. Major genera include Sardinops and Engraulis inhabiting each of the four major eastern boundary currents. The Kuroshio stands out as the non- eastern boundary current with major stocks of sardine (Sardinops melanostictis) and anchovy (Engraulis japonicas). Many hypotheses relate fisheries fluctuations to physics What drives past changes Landings in the US state of California in fish abundance? Overfishing? Environmental variability? How? Why? Warm Conditions Cold Conditions Soutar and Isaacs (1969); Baumgartner et al. -

Tidally Modified Western Boundary Current Drives Interbasin Exchange

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Tidally modifed western boundary current drives interbasin exchange between the Sea of Okhotsk and the North Pacifc Hung‑Wei Shu1,2*, Humio Mitsudera1, Kaihe Yamazaki2,3, Tomohiro Nakamura1, Takao Kawasaki4, Takuya Nakanowatari5, Hatsumi Nishikawa1,4 & Hideharu Sasaki6 The interbasin exchange between the Sea of Okhotsk and the North Pacifc governs the intermediate water ventilation and fertilization of the nutrient‑rich subpolar Pacifc, and thus has an enormous infuence on the North Pacifc. However, the mechanism of this exchange is puzzling; current studies have not explained how the western boundary current (WBC) of the subarctic North Pacifc intrudes only partially into the Sea of Okhotsk. High‑resolution models often exhibit unrealistically small exchanges, as the WBC overshoots passing by deep straits and does not induce exchange fows. Therefore, partial intrusion cannot be solely explained by large‑scale, wind‑driven circulation. Here, we demonstrate that tidal forcing is the missing mechanism that drives the exchange by steering the WBC pathway. Upstream of the deep straits, tidally‑generated topographically trapped waves over a bank lead to cross‑slope upwelling. This upwelling enhances bottom pressure, thereby steering the WBC pathway toward the deep straits. The upwelling is identifed as the source of joint‑efect‑of‑ baroclinicity‑and‑relief (JEBAR) in the potential vorticity equation, which is caused by tidal oscillation instead of tidally‑enhanced vertical mixing. The WBC then hits the island chain and induces exchange fows. This tidal control of WBC pathways is applicable on subpolar and polar regions globally. Te water exchange between the Sea of Okhotsk and the North Pacifc is an essential component of the over- turning circulation that ventilates the intermediate layer of the North Pacifc 1.