HB 338 - Turnaround Elligible Schools Eleanor F

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GCEP EPIC - October 2020 10/6/20, 4�07 PM

GCEP EPIC - October 2020 10/6/20, 407 PM HOME \ CONTACT October 2020 GCEP EPIC The Magazine of the Georgia College of Emergency Physicians IN THIS ISSUE... President's Message Diversity & Inclusion Committee Government Affairs Financial Market News BOD Spotlight Important Dates/GEMLAC President's Message GCEP Members, Life as we know it is beginning to return to some semblance of normalcy. Many emergency departments are beginning to return to pre-pandemic volumes. There has been minimal activity on Governor Kemp's Covid-19 Task Force, but many entities around the state are beginning to return to full capacity. Schools around our John L. Sy, DO, MS, FACEP state have opened or are about to open. It is more President, GCEP important now than ever before to be vigilant. No one is immune, not even the President of the United States (POTUS). We need to focus on physician wellness for our colleagues and ourselves. Please come support GCEP at our annual Lake Oconee meeting - Georgia Emergency Medicine Leadership and Advocacy Conference on December 3-4, 2020. The GCEP Education planning committee and staff have worked very hard to make it possible to attend in the traditional format at the Ritz on Lake Oconee AND new this year we will be offering a virtual option for those who prefer not to travel. Programming will highlight https://ui.constantcontact.com/rnavmap/email/action/print?agentId=1134836320186 Page 1 of 12 GCEP EPIC - October 2020 10/6/20, 407 PM legislators who have been supportive of our advocacy agenda and lectures to improve leadership skills even for those seasoned physicians. -

David Adelman

CHUCK PAYNE COMMITTEES: District 54 Education and Youth, Chair 320-A Coverdell Legislative Office Building Appropriations – Ex Officio 18 Capitol Square, S.W. Finance – Secretary Atlanta, Georgia 30334 Higher Education – Secretary Tel: (404) 463-5402 Public Safety – Ex-Officio State and Local Government Operations [email protected] Vice-Chairman The State Senate Atlanta, Georgia 30334 TO: Senate Education and Youth Committee Members Senator Jason Anavitarte, 31st, Vice Chair Senator Freddie Powell Sims, 12th, Secretary Senator Matt Brass, 28th, Ex- Officio Senator Lindsey Tippins, 37th, Ex-Officio Senator John Albers, 56th Senator Greg Dolezal, 27th Senator Sonya Halpern, 39th Senator Lester Jackson, 2nd Senator Donzella James, 35th Senator Sheila McNeill, 3rd Senator Elena Parent, 42nd From: Chairman, Senator Chuck Payne, 54th DATE: Monday, February 1st, 2021 TIME: 3:30 P.M. LOCATION: CLOB 307 AGENDA: SB 20 (Sen. Payne, 54th) “Relating to the “Georgia Child Advocate for the Protection of Children Act,” so as to revise the composition of the Child Advocate Advisory Committee” SB 42 (Sen. Mullis, 53rd) “Relating to indicators of quality of learning in individual school systems, comparison to state standards, rating schools and school systems, providing information, and uniform definition of “dropout” and “below grade level,” so as to provide that the school climate rating does not include discipline data” Agenda is subject to change at the discretion of the Chairman. cc: Geoff Duncan, Lt. Governor Michael Walker, Legislative Counsel David Cook, Secretary of the Senate Andrew Allison, Senate Press Office Senator Butch Miller, President Pro Tempore Elizabeth Holcomb, Senate Research Office Senator Mike Dugan, Majority Leader Melody DeBussey, Senate Budget Office Governor’s Office, Miranda Williams . -

A Consumer Health Advocate's Guide to the 2017

A CONSUMER HEALTH ADVOCATE’S GUIDE TO THE 2017 GEORGIA LEGISLATIVE SESSION Information for Action 2017 1 2 Contents About Georgians for a Healthy Future » PAGE 2 Legislative Process Overview » PAGE 3 How a Bill Becomes a Law (Chart) » PAGE 8 Constitutional Officers & Health Policy Staff » PAGE 10 Agency Commissioners & Health Policy Staff » PAGE 11 Georgia House of Representatives » PAGE 12 House Committees » PAGE 22 Georgia State Senate » PAGE 24 Senate Committees » PAGE 28 Health Care Advocacy Organizations & Associations » PAGE 30 Media: Health Care, State Government & Political Reporters » PAGE 33 Advocacy Demystified » PAGE 34 Glossary of Terms » PAGE 36 100 Edgewood Avenue, NE, Suite 1015 Atlanta, Georgia 30303 (404) 567-5016 www.healthyfuturega.org ABOUT GEORGIANS FOR A HEALTHY FUTURE Georgians for a Healthy Future (GHF) is a nonprofit health policy and advocacy organiza- tion that provides a voice for Georgia consumers on vital and timely health care issues. Our mission is to build and mobilize a unified voice, vision and leadership to achieve a healthy future for all Georgians. Georgians for a Healthy Future approaches our vision of ensuring access to quality, afford- able health care for all Georgians in three major ways 1) outreach and public education, 2) building, managing, and mobilizing coalitions, and 3) public policy advocacy. GEORGIANS FOR A HEALTHY FUTURE’S 2017 POLICY PRIORITIES INCLUDE: 1. Ensure access to quality, affordable health coverage and care, and protections for all Georgians. 2. End surprise out-of-network bills. 3. Set and enforce network adequacy standards for all health plans in Georgia. 4. Prevent youth substance use disorders through utilizing Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT) in Medicaid. -

2021 State Legislator Pledge Signers

I pledge that, as a member of the state legislature, I will cosponsor, vote for, and defend the resolution applying for an Article V convention for the sole purpose of enacting term limits on Congress. The U.S. Term Limits Article V Pledge Signers 2021 State Legislators 1250 Connecticut Ave NW Suite 200 ALABAMA S022 David Livingston H073 Karen Mathiak Washington, D.C. 20036 Successfully passed a term S028 Kate Brophy McGee H097 Bonnie Rich (202) 261-3532 limits only resolution. H098 David Clark termlimits.org CALIFORNIA H103 Timothy Barr ALASKA H048 Blanca Rubio H104 Chuck Efstration H030 Ron Gillham H105 Donna McLeod COLORADO H110 Clint Crowe ARKANSAS H016 Andres Pico H119 Marcus Wiedower H024 Bruce Cozart H022 Margo Herzl H131 Beth Camp H042 Mark Perry H039 Mark Baisley H141 Dale Washburn H071 Joe Cloud H048 Tonya Van Beber H147 Heath Clark H049 Michael Lynch H151 Gerald Greene ARIZONA H060 Ron Hanks H157 Bill Werkheiser H001 Noel Campbell H062 Donald Valdez H161 Bill Hitchens H001 Judy Burges H063 Dan Woog H162 Carl Gilliard H001 Quang Nguyen H064 Richard Holtorf H164 Ron Stephens H002 Andrea Dalessandro S001 Jerry Sonnenberg H166 Jesse Petrea H002 Daniel Hernandez S010 Larry Liston H176 James Burchett H003 Alma Hernandez S023 Barbara Kirkmeyer H177 Dexter Sharper H005 Leo Biasiucci H179 Don Hogan H006 Walter Blackman CONNECTICUT S008 Russ Goodman H007 Arlando Teller H132 Brian Farnen S013 Carden Summers H008 David Cook H149 Kimberly Fiorello S017 Brian Strickland H011 Mark Finchem S021 Brandon Beach H012 Travis Grantham FLORIDA S027 Greg Dolezal H014 Gail Griffin Successfully passed a term S030 Mike Dugan H015 Steve Kaiser limits only resolution. -

REPRODUCTIVE RIGHTS Reproductive Rights Scorecard Methodology

LEGISLATIVE SCORECARD 2020 REPRODUCTIVE RIGHTS Reproductive Rights Scorecard Methodology Who are we? The ACLU of Georgia envisions a state that guarantees all persons the civil liberties and rights con- tained in the United States and Georgia Constitutions and Bill of Rights. The ACLU of Georgia en- hances and defends the civil liberties and rights of all Georgians through legal action, legislative and community advocacy and civic education and engagement. We are an inclusive, nonpartisan, state- wide organization powered by our members, donors and active volunteers. How do we select the bills to analyze? Which bills did we choose, and why? Throughout the ACLU’s history, great strides To ensure a thorough review of Georgia’s repro- have been made to protect women’s rights, in- ductive justice and women’s rights bills, we scored cluding women’s suffrage, education, women eight bills dating back to 2012. Each legislator entering the workforce, and most recently, the Me was scored on bills they voted on since being elect- Too Movement. Despite this incredible progress, ed (absences and excuses were not counted to- women still face discrimination and are forced to wards the score). Because the bills we chose were constantly defend challenges to their ability to voted on throughout the years of 2012 to 2020, make private decisions about reproductive health. some legislators are scored on a different num- Overall, women make just 78 cents for every ber of bills because they were not present in the dollar earned by men. Black women earn only legislature when every bill scored was voted on or 64 cents and Latinas earn only 54 cents for each they were absent/excused from the vote — these dollar earned by white men. -

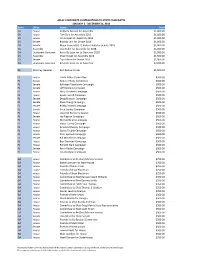

Norfolk Southern Corporation Contributions

NORFOLK SOUTHERN CORPORATION CONTRIBUTIONS TO CANDIDATES AND POLITICAL COMMITTEES JANUARY 1 ‐ DECEMBER 31, 2018* STATE RECIPIENT OF CORPORATE POLITICAL FUNDS AMOUNT DATE ELECTION OFFICE OR COMMITTEE TYPE IN Eric Holcomb $1,000 01/18/2018 Primary 2018 Governor US National Governors Association $30,000 01/31/2018 N/A 2018 Association Conf. Acct. SC South Carolina House Republican Caucus $3,500 02/14/2018 N/A 2018 State Party Cmte SC South Carolina Republican Party (State Acct) $1,000 02/14/2018 N/A 2018 State Party Cmte SC Senate Republican Caucus Admin Fund $3,500 02/14/2018 N/A 2018 State Party Non‐Fed Admin Acct SC Alan Wilson $500 02/14/2018 Primary 2018 State Att. General SC Lawrence K. Grooms $1,000 03/19/2018 Primary 2020 State Senate US Democratic Governors Association (DGA) $10,000 03/19/2018 N/A 2018 Association US Republican Governors Association (RGA) $10,000 03/19/2018 N/A 2018 Association GA Kevin Tanner $1,000 04/16/2018 Primary 2018 State House GA David Ralston $1,000 04/16/2018 Primary 2018 State House IN Ryan Hatfield $750 04/16/2018 Primary 2018 State House IN Gregory Steuerwald $500 04/16/2018 Primary 2018 State House IN Karen Tallian $750 04/16/2018 Primary 2018 State Senate IN Blake Doriot $750 04/16/2018 Primary 2020 State Senate IN Dan Patrick Forestal $750 04/16/2018 Primary 2018 State House GA Bill Werkheiser $400 04/26/2018 Primary 2018 State House GA Deborah Silcox $400 04/26/2018 Primary 2018 State House GA Frank Ginn $500 04/26/2018 Primary 2018 State Senate GA John LaHood $500 04/26/2018 Primary 2018 State -

2021 State Senate Legislative Districts

20212021 GeorgiaGeorgia SenateSenate DistrictsDistricts §¨¦75 Bartow Forsyth Cherokee 575 24 §¨¦ §¨¦ Catoosa Tri State Fannin Dade Blue Ridge Towns Rabun Brandon Beach (R-21) Michelle Au (D-48) EMC John Albers (R-56) Clint Dixon (R-45) Mountain EMC Habersham §¨¦575 §¨¦59 Gwinnett Whitfield Murray Union EMC Lindsey Tippins (R-37) Gilmer Cobb Kay Kirkpatrick (R-32) Habersham Paulding Jeff Mullis (R-53) Chuck Payne (R-54) White Sheikh Rahman (D-05) Walker Steve Gooch (R-51) North Georgia EMC Sally Harrell (D-40) Amicalola EMCLumpkin Nikki Merritt (D-09) Stephens Gordon Michael 'Doc' Rhett (D-33) Jennifer Jordan (D-06) Chattooga Pickens Bo Hatchett (R-50) Dawson §¨¦85 Kim Jackson (D-41) Cherokee Franklin Hart 75 Brandon Beach (R-21) Banks Douglas §¨¦ Elena Parent (D-42) Gloria Butler (D-55) Hall Horacena Tate (D-38) DeKalb Floyd Bruce Thompson (R-14) Greg Dolezal (R-27) Hart EMC 20 Butch Miller (R-49) Jackson Fulton §¨¦ Bartow Forsyth Chuck Hufstetler (R-52) §¨¦575 Sawnee Jackson EMC §¨¦675 §¨¦985 Donzella James (D-35) Nan Orrock (D-36) 85 EMC Frank Ginn (R-47) Tonya Anderson (D-43) Polk Cobb EMC §¨¦ Madison Elbert Sonya Halpern (D-39) Paulding §¨¦85 Rockdale Barrow GreyStone Clarke Clayton Newton 285 Oglethorpe Power §¨¦ Gwinnett Gail Davenport (D-44) Emanual Jones (D-10) Corporation Cobb Bill Cowsert (R-46) 85 Oconee Henry §¨¦ Wilkes Lincoln 20 Walton Jason Anavitarte (R-31) §¨¦ Fayette DeKalb 85 Valencia Seay (D-34) Haralson §¨¦ Brian Strickland (R-17) Douglas Rockdale Walton EMC Rayle EMCLee Anderson (R-24) Coweta Carroll §¨¦675 Snapping Shoals Morgan EMC Fulton EMC Taliaferro Carroll Columbia Clayton Newton McDuffie §¨¦20 Mike Dugan (R-30) Fayette Henry Greene §¨¦520 Coweta-Fayette Warren Spalding Jasper Richmond EMC Butts Brian Strickland (R-17) Heard Burt Jones (R-25) Jefferson Energy Harold V. -

Official Republican Party Primary and Nonpartisan General Election Ballot of the State of Georgia May 22, 2018

PICKENS COUNTY OFFICIAL ABSENTEE/PROVISIONAL/CHALLENGED BALLOT OFFICIAL REPUBLICAN PARTY PRIMARY AND NONPARTISAN GENERAL ELECTION BALLOT OF THE STATE OF GEORGIA MAY 22, 2018 To vote, blacken the Oval ( ) next to the candidate of your choice. To vote for a person whose name is not on the ballot, manually WRITE his or her name in the write-in section and blacken the Oval ( ) next to the write-in section. If you desire to vote YES or NO for a PROPOSED QUESTION, blacken the corresponding Oval ( ). Use only blue or black pen or pencil. Do not vote for more candidates than the number allowed for each specific office. Do not cross out or erase. If you erase or make other marks on the ballot or tear the ballot, your vote may not count. If you change your mind or make a mistake, you may return the ballot by writing “Spoiled” across the face of the ballot and return envelope. You may then mail the spoiled ballot back to your county board of registrars, and you will be issued another official absentee ballot. Alternatively, you may surrender the ballot to the poll manager of an early voting site within your county or the precinct to which you are assigned. You will then be permitted to vote a regular ballot. "I understand that the offer or acceptance of money or any other object of value to vote for any particular candidate, list of candidates, issue, or list of issues included in this election constitutes an act of voter fraud and is a felony under Georgia law." [OCGA 21-2-284(e), 21-2-285(h) and 21-2-383(a)] For Governor For State School Superintendent For County Commissioner (Vote for One) (Vote for One) District 1 (Vote for One) L.S. -

August 23, 2021 VIA EMAIL Matthew Mashburn Georgia State Elections

August 23, 2021 VIA EMAIL Matthew Mashburn Georgia State Elections Board Member PO Box 451 Cartersville, GA 30120 [email protected] Re: Open Records Request Dear State Election Board Member Mashburn: Pursuant to the Georgia Open Records Law (O.C.G.A. §§ 50-18-70 et seq.), American Oversight makes the following request for records. Requested Records American Oversight requests that you produce the following within three business days: 1. All records reflecting communications (including emails, email attachments, text messages, messages on messaging platforms (such as Slack, GChat or Google Hangouts, Lync, Skype, Facebook Messenger, Twitter Direct Messages, or WhatsApp), telephone call logs, calendar invitations, calendar entries, meeting notices, meeting agendas, informational material, draft legislation, talking points, any handwritten or electronic notes taken during any oral communications, summaries of any oral communications, or other materials) between (a) State Election Board member Matthew Mashburn, and (b) any of the Georgia General Assembly members or staff listed below (including, but not limited to, at the listed email addresses). Georgia State Senators: i. John Albers ([email protected]) ii. Matt Brass ([email protected]) iii. Kay Kirkpatrick ([email protected]) iv. Jason Anavitarte ([email protected]) v. Lee Anderson ([email protected]) vi. Dean Burke ([email protected]) vii. Max Burns ([email protected]) viii. Clint Dixon ([email protected]) ix. Greg Dolezal ([email protected]) x. Mike Dugan ([email protected]) xi. Frank Ginn ([email protected]) xii. Steve Gooch ([email protected]) xiii. -

State Office Name Total CA House Anthony Rendon for Assembly

AFLAC CORPORATE CONTRIBUTIONS TO STATE CANDIDATES JANUARY 1 - DECEMBER 31, 2016 State Office Name Total CA House Anthony Rendon for Assembly $1,000.00 CA House Tom Daly for Assembly 2016 $1,000.00 CA House Jim Cooper for Assembly 2016 $1,000.00 CA Senate Ricardo Lara for Senate 2016 $1,000.00 CA Senate Major General (RET) Richard Roth for Senate 2016 $1,000.00 CA Assembly Jean Fuller for Assembly for 2018 $1,000.00 CA Lieutenant Governor Kevin De Leon for Lt. Governor 2018 $1,000.00 CA Assembly Chad Mayes for Assembly 2016 $1,500.00 CA Senate Toni Atkins for Senate 2016 $1,500.00 CA Lieutenant Governor Kevin De Leon for Lt. Governor $2,000.00 DC Attorney General Karl Racine for AG $1,500.00 FL House Frank Artiles Committee $500.00 FL Senate Anitere Flores Committee $500.00 FL Senate Kathleen Passidomo Campaign $500.00 FL Senate Jeff Clemens Campaign $500.00 FL House Holly Raschein Campaign $500.00 FL House Gayle Harrell Campaign $500.00 FL Senate Doug Broxson Campaign $500.00 FL Senate Dana Young Campaign $500.00 FL Senate Bobby Powell Campaign $500.00 FL Senate Greg Steube Campaign $500.00 FL House Jeanette Nunez Campaign $500.00 FL Senate Joe Negron Campaign $500.00 FL House Michael Bileca Campaign $500.00 FL House Victor Torres Campaign $500.00 FL House Amanda Murphy Campaign $500.00 FL House Carols Trujilio Campaign $500.00 FL House Chris Sprowls Campaign $500.00 FL Senate Bill Montford Campaign $500.00 FL House Ben Diamond Campaign $500.00 FL House Richard Stark Campaign $500.00 FL Senate Kevin Rader Campaign $500.00 FL House Jim Waldman Campaign $500.00 GA House Committee to Re-Elect Michele Henson $250.00 GA House Eddie Lumsden for State House $250.00 GA House Friends of David Casas $250.00 GA House Friends of Shaw Blackmon $250.00 GA House Friends of Shaw Blackmon $250.00 GA House Committee to Elect Earnest Coach Williams $350.00 GA House Committee to Elect Earnest Smith $350.00 GA House Committee to Elect Erica Thomas $350.00 GA House Committee to Elect Thomas S. -

2016 Political Corporate Contributions

2016 POLITICAL CORPORATE CONTRIBUTIONS LAST NAME FIRST NAME COMMITTEE NAME STATE OFFICE DISTRICT PARTY 2016 TOTAL ($) BIZ PAC AL Non-Partisan 15,000 Free Enterprise PAC AL Non-Partisan 10,000 Mainstream PAC AL Non-Partisan 15,000 Arizona Republican Party AZ Republican 2,000 Senate Republican Leadership Fund AZ Republican 12,500 Acosta Dante Dante Acosta for Assembly 2016 CA Representative CA038 Republican 2,500 Allen Travis Travis Allen for Assembly 2016 CA Representative CA072 Republican 2,500 Bates Pat Pat Bates for Senate 2018 CA Senator CA036 Republican 1,700 Bigelow Frank Friends of Frank Bigelow for Assembly 2016 CA Representative CA005 Republican 4,200 Bradford Steven Steven Bradford for Senate 2016 CA Senator CA035 Democratic 1,900 Brough William Bill Brough For State Assembly 2016 CA Representative CA073 Republican 5,500 Calderon Ian Ian Calderon For Assembly 2016 CA Representative CA057 Democratic 2,500 Cannella Anthony Cannella for Lt. Governor 2018 CA Lt. Governor Republican 4,200 Chang Ling-Ling Chang for Senate 2016 CA Senator CA029 Republican 7,200 Dahle Brian Brian Dahle for Assembly 2016 CA Representative CA001 Republican 5,500 Daly Tom Tom Daly for Assembly 2016 CA Representative CA069 Democratic 2,500 Fuller Jean Jean Fuller for Assembly 2018 CA Senator CA016 Republican 4,200 Gaines Beth Beth Gaines 2014 Assembly Officeholder Account CA Representative CA006 Republican 2,000 Gallagher James James Gallagher for Assembly 2016 CA Representative CA003 Republican 4,200 Grove Shannon Shannon Grove for Senate 2018 CA Representative -

The Latino Electorate in Georgia Continues to Grow and to Vote Latina Voters Lead the Voter Participation with Record-Breaking Turnout

2016: The Latino Electorate in Georgia Continues To Grow and To Vote Latina voters lead the voter participation with record-breaking turnout July 6, 2017 Authored by: Jerry Gonzalez, M.P.A. Executive Director GALEO & the GALEO Latino Community Development Fund Voter Turn-Out Database Analysis Conducted by: Trey Hood, Ph.D. Department of Political Science, University of Georgia (Athens, GA) & Latino Surname Match Conducted by: Dorian Caal, Director of Civic Engagement Research NALEO Educational Fund (Los Angeles, CA) Editing Contributions by: Harvey Soto Program Coordinator The GALEO Latino Community Development Fund Table of Contents Executive Summary ........................................................................................................... 2 Statewide Latino Electorate .............................................................................................. 4 NALEO Methodology for Identifying Latino Voters ............................................................................................ 4 Limitations of Self-Identification for the Purpose of Tagging Latinos ........................................................ 4 Statewide Results ............................................................................................................................................................... 7 Age of the Georgia Latino Electorate ......................................................................................................................... 9 Dates of Voter Registration ........................................................................................................................................