2017 European Guideline for the Management of Pelvic Inflammatory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Premature Ovarian Insufficiency

biomedicines Review Premature Ovarian Insufficiency: Procreative Management and Preventive Strategies Jennifer J. Chae-Kim 1 and Larisa Gavrilova-Jordan 2,* 1 Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, East Carolina University, Greenville, NC 27834, USA; [email protected] 2 Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Augusta University, Augusta, GA 30912, USA * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-706-721-3832 Received: 30 November 2018; Accepted: 24 December 2018; Published: 28 December 2018 Abstract: Premature ovarian insufficiency (POI) is the loss of normal hormonal and reproductive function of ovaries in women before age 40 as the result of premature depletion of oocytes. The incidence of POI increases with age in reproductive-aged women, and it is highest in women by the age of 40 years. Reproductive function and the ability to have children is a defining factor in quality of life for many women. There are several methods of fertility preservation available to women with POI. Procreative management and preventive strategies for women with or at risk for POI are reviewed. Keywords: premature ovarian insufficiency; in vitro fertilization; donor oocyte; fertility preservation 1. Introduction Premature ovarian insufficiency (POI) is the loss of normal hormonal and reproductive function of ovaries in women before age 40 as the result of premature depletion of oocytes. POI is characterized by elevated gonadotrophin levels, hypoestrogenism, and amenorrhea, occurring years before the average age of menopause. Previously referred to as ovarian failure or early menopause, POI is now understood to be a condition that encompasses a range of impaired ovarian function, with clinical implications overlapping but not synonymous to that of physiologic menopause. -

The Relations Between Anemia and Female Adolescent's Dysmenorrhea

Universitas Ahmad Dahlan International Conference on Public Health The Relations Between Anemia and Female Adolescent’s Dysmenorrhea Paramitha Amelia Kusumawardani, Cholifah Diploma Program of Midwifery, Health Science Faculty , University of Muhammadiyah Sidoarjo Article Info ABSTRACT Keyword: Dysmenorrhea described as painful cramps in the lower abdomen that Anemia, occur during menstruation and the infection indications, pelvic disease Dysmenorrhea, moreover in the severe cases it caused fainted. The women who Female adolescents. complained dysmenorrhea problems mostly are who experience menstruation at any age. That means there is no limits age and usually dysmenorrhea often occur with dizziness, cold sweating, even fainted. In some countries the dysmenorrhea problem happens quite high as happened in the United States found 60-91% while in Indonesia amounted to 64.25%. as many as 45-75% of female adolescent experienced dysmenorrhea with the chronic or severe pain that effected to their everyday activities The number of teenagers who experience dysmenorrhea is due to high cases of anemia, irregular exercise, and lack of knowledge of nutritional status. In the previous study there are 85% of female adolescent experience dysmenorrhea. The method of this study is a correlational method with cross sectional approach. The data collecting method examining Hb levels. The population and sample of this study was 40 female adolescent The result showed that the female adolescent who had dysmenorrhea with anemia was 26 (92.4%). From the calculation by Exact Fisher the correlation between anemia and dysmenorrhea cases among female adolescent P <0.05 and p = 0.003, there was significant correlation between adolescent’s dysmenorrhea. Based on the result of statistic analysis, it can be concluded that the anemia can be categorized as one of dysmenorrhea causes. -

ICD10 Diagnoses FY2018 AHD.Com

ICD10 Diagnoses FY2018 AHD.com A020 Salmonella enteritis A5217 General paresis B372 Candidiasis of skin and nail A040 Enteropathogenic Escherichia coli A523 Neurosyphilis, unspecified B373 Candidiasis of vulva and vagina infection A528 Late syphilis, latent B3741 Candidal cystitis and urethritis A044 Other intestinal Escherichia coli A530 Latent syphilis, unspecified as early or B3749 Other urogenital candidiasis infections late B376 Candidal endocarditis A045 Campylobacter enteritis A539 Syphilis, unspecified B377 Candidal sepsis A046 Enteritis due to Yersinia enterocolitica A599 Trichomoniasis, unspecified B3781 Candidal esophagitis A047 Enterocolitis due to Clostridium difficile A6000 Herpesviral infection of urogenital B3789 Other sites of candidiasis A048 Other specified bacterial intestinal system, unspecified B379 Candidiasis, unspecified infections A6002 Herpesviral infection of other male B380 Acute pulmonary coccidioidomycosis A049 Bacterial intestinal infection, genital organs B381 Chronic pulmonary coccidioidomycosis unspecified A630 Anogenital (venereal) warts B382 Pulmonary coccidioidomycosis, A059 Bacterial foodborne intoxication, A6920 Lyme disease, unspecified unspecified unspecified A7740 Ehrlichiosis, unspecified B387 Disseminated coccidioidomycosis A080 Rotaviral enteritis A7749 Other ehrlichiosis B389 Coccidioidomycosis, unspecified A0811 Acute gastroenteropathy due to A879 Viral meningitis, unspecified B399 Histoplasmosis, unspecified Norwalk agent A938 Other specified arthropod-borne viral B440 Invasive pulmonary -

Gonorrhea Can Be Easily Cured with Antibiotics from a If You Are Pregnant, It Is Even More Important to Get Health Care Provider

GET YOURSELF TESTED Testing is confidential. If you are under 18 years old, you can consent to be checked and treated for STIs. What if I don’t get treated? What if I am pregnant? Gonorrhea can be easily cured with antibiotics from a If you are pregnant, it is even more important to get health care provider. tested by your health care provider and treated if you have gonorrhea. Left untreated, gonorrhea can be However, if gonorrhea is not treated, it can cause Gonorrhea passed to your baby during vaginal delivery and can permanent damage: cause serious health problems. • Your risk of getting other STIs, like gonorrhea or • Babies are usually treated with an antibiotic HIV increases. shortly after birth. If a baby with gonorrhea isn’t • In females, untreated gonorrhea can increase the treated, they may become blind. chances of getting pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), an infection of the reproductive organs, which can make it hard to get pregnant or carry a To learn more baby full-term. Contact a health care provider or your local STI clinic. • In males, untreated gonorrhea can lead to sterility To learn more about STIs, or to find your local (inability to make sperm and have children). STI clinic, visit www.health.ny.gov/STD. You can find other STI testing locations at What about my sex partner(s)? https://gettested.cdc.gov. Gonorrhea is a sexually transmitted infection. If you have gonorrhea, your sex partner(s) should get tested. If they have gonorrhea, they will need to take medicine to cure it. -

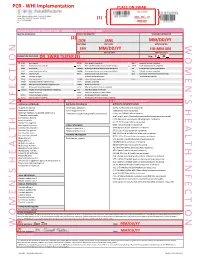

Womens Health Requisition Forms

PCR - WHI Implementation PLACE ON SWAB 10854 Midwest Industrial Blvd. St. Louis, MO 63132 MM DD YY Phone: (314) 200-3040 | Fax (314) 200-3042 (1) CLIA ID #26D0953866 JANE DOE v3 PCR MOLECULAR REQUISITION - WOMEN'S HEALTH INFECTION PRACTICE INFORMATION PATIENT INFORMATION *SPECIMEN INFORMATION (2) DOE JANE MM/DD/YY LAST NAME FIRST NAME DATE COLLECTED W O M E ' N S H E A L T H I F N E C T I O N SSN MM/DD/YY HH:MM AM SSN DATE OF BIRTH TIME COLLECTED REQUESTING PHYSICIAN: DR. SWAB TESTER (3) Sex: F X M (4) Diagnosis Codes X N76.0 Acute vaginitis B37.49 Other urogenital candidiasis A54.9 Gonococcal infection, unspecified N76.1 Subacute and chronic vaginitis N89.8 Other specified noninflammatory disorders of vagina A59.00 Urogenital trichomoniasis, unspecified N76.2 Acute vulvitis O99.820 Streptococcus B carrier state complicating pregnancy A64 Unspecified sexually transmitted disease N76.3 Subacute and chronic vulvitis O99.824 Streptococcus B carrier state complicating childbirth A74.9 Chlamydial infection, unspecified N76.4 Abscess of vulva B95.1 Streptococcus, group B, as the cause Z11.3 Screening for infections with a predmoninantly N76.5 Ulceration of vagina of diseases classified elsewhere sexual mode of trasmission N76.6 Ulceration of vulva Z22.330 Carrier of group B streptococcus Other: N76.81 Mucositis(ulcerative) of vagina and vulva N70.91 Salpingitis, unspecified N76.89 Other specified inflammation of vagina and vulva N70.92 Oophoritis, unspecified N95.2 Post menopausal atrophic vaginitis N71.9 Inflammatory disease of uterus, unspecified -

Get the Facts About Necrotizing Fasciitis: “Flesh-Eating Disease”

Get the facts about necrotizing fasciitis: “Flesh-eating Disease” What is necrotizing fasciitis? There are many strains of bacteria that can cause the flesh-eating disease known as necrotizing fasciitis, but most cases are caused by a bacteria called group A strep, or Streptococcus pyogenes. More common infections with group A strep are not only strep throat, but also a skin infection called impetigo. Flesh-eating strep infections or necrotizing fasciitis is considered rare. Necrotizing fasciitis is a treatable disease. Only certain rare bacterial strains are able to cause necrotizing fasciitis, but these infections progress rapidly so the sooner one seeks medical care, the better the chances of survival. The bacteria actually cause extensive tissue damage because the tissues under the skin and those surrounding muscle and body organs are destroyed; necrotizing fasciitis is extensive and can lead to death. Is this a new disease? No. The flesh-eating infections have been described as early as the fifth century B.C. based on written accounts of necrotizing fasciitis by Hippocrates. More than 2,000 cases of this condition were reported among soldiers during the Civil War. Cases in the U.S. are generally infrequent, although small epidemics have occurred, such as the 1996 outbreak in San Francisco among injection drug abusers using contaminated “black tar” heroin. What are the signs and symptoms? Persons with the flesh-eating infection know something is wrong because of extreme pain in the infected area. Generally, an infection begins at a surgical wound or because of accidental trauma—sometimes without an obvious break in the skin—accompanied by severe pain, followed by swelling, fever, and sometimes confusion. -

What Is Staphylococcus Aureus (Staph)?

What is Staphylococcus aureus (staph)? Staphylococcus aureus, often referred to simply as "staph," are bacteria commonly carried on the skin or in the nose of healthy people. Approximately 25% to 30% of the population is colonized (when bacteria are present, but not causing an infection) in the nose with staph bacteria. Sometimes, staph can cause an infection. Staph bacteria are one of the most common causes of skin infections in the United States. Most of these skin infections are minor (such as pimples and boils) and can be treated without antibiotics (also known as antimicrobials or antibacterials). However, staph bacteria also can cause serious infections (such as surgical wound infections, bloodstream infections, and pneumonia). What is MRSA (methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus)? Some staph bacteria are resistant to antibiotics. MRSA is a type of staph that is resistant to antibiotics called beta-lactams. Beta-lactam antibiotics include methicillin and other more common antibiotics such as oxacillin, penicillin and amoxicillin. While 25% to 30% of the population is colonized with staph, approximately 1% is colonized with MRSA. Who gets staph or MRSA infections? Staph infections, including MRSA, occur most frequently among persons in hospitals and healthcare facilities (such as nursing homes and dialysis centers) who have weakened immune systems. These healthcare-associated staph infections include surgical wound infections, urinary tract infections, bloodstream infections, and pneumonia. Are people who are positive for the human immune deficiency virus (HIV) at increased risk for MRSA? Should they be taking special precautions? People with weakened immune systems, which include some patients with HIV infection, may be at risk for more severe illness if they get infected with MRSA. -

Menstrual Disorders Susan Hayden Gray, MD* Practice Gap 1

Article genital system disorders Menstrual Disorders Susan Hayden Gray, MD* Practice Gap 1. Dysmenorrhea, amenorrhea, and abnormal vaginal bleeding affect the majority of Author Disclosure adolescent females, impacting quality of life and school attendance. Patient-centered Dr Gray has disclosed adolescent care should include searching for, assessing, and managing menstrual concerns. no financial 2. Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is the most common endocrinopathy in young relationships relevant adult women, and pediatricians should recognize, monitor, educate, and manage their to this article. This patients who fit the medical profile for PCOS based on any/all of the three sets of commentary does diagnostic criteria. contain a discussion of an unapproved/ Objectives After reading this article, readers should be able to: investigative use of a commercial product/ 1. Define primary and secondary amenorrhea and list the differential diagnosis for each. device. 2. Recognize the importance of a sensitive urine pregnancy test early in the evaluation of menstrual disorders, regardless of stated sexual history. 3. Know that polycystic ovary syndrome is a common cause of secondary amenorrhea in adolescents and may present with oligomenorrhea or abnormal uterine bleeding. 4. Recognize that eating disordered behaviors are a common cause of secondary amenorrhea and irregular bleeding, and treatment of the eating disordered behavior is the best recommendation to ensure resumption of regular menses and long-term bone health. 5. Know the differential diagnosis of abnormal uterine bleeding and describe the preferred treatment, recognizing the central importance of iron replacement. 6. Understand the prevalence of primary dysmenorrhea and its role in causing recurrent school absence in young women, and describe its evaluation and management. -

Endometritis Caused by Chlamydia Trachomatis

Br J Vener Dis 1981; 57:191-5 Endometritis caused by Chlamydia trachomatis P-A MARDH,* B R M0LLER,t H J INGERSELV,* E NUSSLER,* L WESTROM,§ AND P W0LNER-HANSSEN§ From the *Institute of Medical Microbiology, University of Lund, Sweden; the tlnstitute of Medical Microbiology, University of Aarhus, Denmark; the *Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Municipal Hospital, Aarhus, Denmark; and the §Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, University Hospital, Lund, Sweden SUMMARY Chlamydia trachomatis was found to be the aetiological agent of endometritis in three women with concomitant signs of salpingitis. All patients developed a significant antibody response to the organism. Chlamydia were recovered from aspirated uterine contents of two patients and darkfield examination of histological sections showed chlamydial inclusions in endometrial cells in one patient. Thus, C trachomatis can be recovered from the endometrium of patients in whom the cervical culture result is negative. In one patient curettage showed endometritis with a characteristic plasma-cell infiltration. The occurrence of chlamydial endometritis may explain why irregular bleeding is a common finding in patients with salpingitis. It also suggests a canalicular spread of chlamydia from the cervix to the Fallopian tubes. Introduction hominis and Ureaplasma urealyticum by cotton- tipped wooden sticks. Specimens for the isolation of Chlamydia trachomatis has been associated with N gonorrhoeae from the cervix and rectum were cervicitis' and salpingitis,2 and perihepatitis may collected with cotton-tipped wooden swabs treated occur in women with chlamydial genital infection.3 with charcoal. Salpingitis caused by chlamydia4 and gonococci5 are histologically similar. Gonococcal salpingitis is an Endometrial contents endosalpingitis and the infection spreads to the For the collection of end6metrial contents, a plastic Fallopian tubes from the cervix via the tube (armoured with a mandrin) was introduced endometrium.5 Experimental salpingitis in monkeys through the cervical canal. -

N35.12 Postinfective Urethral Stricture, NEC, Female N35.811 Other

N35.12 Postinfective urethral stricture, NEC, female N35.811 Other urethral stricture, male, meatal N35.812 Other urethral bulbous stricture, male N35.813 Other membranous urethral stricture, male N35.814 Other anterior urethral stricture, male, anterior N35.816 Other urethral stricture, male, overlapping sites N35.819 Other urethral stricture, male, unspecified site N35.82 Other urethral stricture, female N35.911 Unspecified urethral stricture, male, meatal N35.912 Unspecified bulbous urethral stricture, male N35.913 Unspecified membranous urethral stricture, male N35.914 Unspecified anterior urethral stricture, male N35.916 Unspecified urethral stricture, male, overlapping sites N35.919 Unspecified urethral stricture, male, unspecified site N35.92 Unspecified urethral stricture, female N36.0 Urethral fistula N36.1 Urethral diverticulum N36.2 Urethral caruncle N36.41 Hypermobility of urethra N36.42 Intrinsic sphincter deficiency (ISD) N36.43 Combined hypermobility of urethra and intrns sphincter defic N36.44 Muscular disorders of urethra N36.5 Urethral false passage N36.8 Other specified disorders of urethra N36.9 Urethral disorder, unspecified N37 Urethral disorders in diseases classified elsewhere N39.0 Urinary tract infection, site not specified N39.3 Stress incontinence (female) (male) N39.41 Urge incontinence N39.42 Incontinence without sensory awareness N39.43 Post-void dribbling N39.44 Nocturnal enuresis N39.45 Continuous leakage N39.46 Mixed incontinence N39.490 Overflow incontinence N39.491 Coital incontinence N39.492 Postural -

AMENORRHOEA Amenorrhoea Is the Absence of Menses in a Woman of Reproductive Age

AMENORRHOEA Amenorrhoea is the absence of menses in a woman of reproductive age. It can be primary or secondary. Secondary amenorrhoea is absence of periods for at least 3 months if the patient has previously had regular periods, and 6 months if she has previously had oligomenorrhoea. In contrast, oligomenorrhoea describes infrequent periods, with bleeds less than every 6 weeks but at least one bleed in 6 months. Aetiology of amenorrhea in adolescents (from Golden and Carlson) Oestrogen- Oestrogen- Type deficient replete Hypothalamic Eating disorders Immaturity of the HPO axis Exercise-induced amenorrhea Medication-induced amenorrhea Chronic illness Stress-induced amenorrhea Kallmann syndrome Pituitary Hyperprolactinemia Prolactinoma Craniopharyngioma Isolated gonadotropin deficiency Thyroid Hypothyroidism Hyperthyroidism Adrenal Congenital adrenal hyperplasia Cushing syndrome Ovarian Polycystic ovary syndrome Gonadal dysgenesis (Turner syndrome) Premature ovarian failure Ovarian tumour Chemotherapy, irradiation Uterine Pregnancy Androgen insensitivity Uterine adhesions (Asherman syndrome) Mullerian agenesis Cervical agenesis Vaginal Imperforate hymen Transverse vaginal septum Vaginal agenesis The recommendations for those who should be evaluated have recently been changed to those shown below. (adapted from Diaz et al) Indications for evaluation of an adolescent with primary amenorrhea 1. An adolescent who has not had menarche by age 15-16 years 2. An adolescent who has not had menarche and more than three years have elapsed since thelarche 3. An adolescent who has not had a menarche by age 13-14 years and no secondary sexual development 4. An adolescent who has not had menarche by age 14 years and: (i) there is a suspicion of an eating disorder or excessive exercise, or (ii) there are signs of hirsutism, or (iii) there is suspicion of genital outflow obstruction Pregnancy must always be excluded. -

Abscesses Are a Serious Problem for People Who Shoot Drugs

Where to Get Your Abscess Seen Abscesses are a serious problem for people who shoot drugs. But what the hell are they and where can you go for care? What are abscesses? Abscesses are pockets of bacteria and pus underneath you skin and occasionally in your muscle. Your body creates a wall around the bacteria in order to keep the bacteria from infecting your whole body. Another name for an abscess is a “soft tissues infection”. What are bacteria? Bacteria are microscopic organisms. Bacteria are everywhere in our environment and a few kinds cause infections and disease. The main bacteria that cause abscesses are: staphylococcus (staff-lo-coc-us) aureus (or-e-us). How can you tell when you have an abscess? Because they are pockets of infection abscesses cause swollen lumps under the skin which are often red (or in darker skinned people darker than the surrounding skin) warm to the touch and painful (often VERY painful). What is the worst thing that can happen? The worst thing that can happen with abscesses is that they can burst under your skin and cause a general infection of your whole body or blood. An all over bacterial infection can kill you. Another super bad thing that can happen is a endocarditis, which is an infection of the lining of your heart, and “septic embolism”, which means that a lump of the contaminates in your abscess get loose in your body and lodge in your lungs or brain. Why do abscesses happen? Abscesses are caused when bad bacteria come in to contact with healthy flesh.