The First Vision Grew out of the Process of Developing a Plan for Record Keeping in the Early Years of the Church

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Secret Mormon Meetings of 1922

University of Nevada, Reno THE SECRET MORMON MEETINGS OF 1922 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History By Shannon Caldwell Montez C. Elizabeth Raymond, Ph.D. / Thesis Advisor December 2019 Copyright by Shannon Caldwell Montez 2019 All Rights Reserved UNIVERSITY OF NEVADA RENO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL We recommend that the thesis prepared under our supervision by SHANNON CALDWELL MONTEZ entitled The Secret Mormon Meetings of 1922 be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS C. Elizabeth Raymond, Ph.D., Advisor Cameron B. Strang, Ph.D., Committee Member Greta E. de Jong, Ph.D., Committee Member Erin E. Stiles, Ph.D., Graduate School Representative David W. Zeh, Ph.D., Dean, Graduate School December 2019 i Abstract B. H. Roberts presented information to the leadership of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in January of 1922 that fundamentally challenged the entire premise of their religious beliefs. New research shows that in addition to church leadership, this information was also presented during the neXt few months to a select group of highly educated Mormon men and women outside of church hierarchy. This group represented many aspects of Mormon belief, different areas of eXpertise, and varying approaches to dealing with challenging information. Their stories create a beautiful tapestry of Mormon life in the transition years from polygamy, frontier life, and resistance to statehood, assimilation, and respectability. A study of the people involved illuminates an important, overlooked, underappreciated, and eXciting period of Mormon history. -

Ponder the New Proclamation.Pdf

Ponder THE NEWProclamation A 9-WEEK COUNTDOWN TO GENERAL CONFERENCE FIND THE LINKS TO TALKS & VIDEOS AT LDSLIVING.COM/PROCLAMATION AUGUST 2–8 We solemnly proclaim that God loves His children in every nation of the world. God the Father has given us the divine birth, the incomparable life, and the infinite atoning sacrifice of His Beloved Son, Jesus Christ. By the power of the Father, Jesus rose again and gained the victory over death. He is our Savior, our Exemplar, and our Redeemer. SUNDAY SCRIPTURE: Read and ponder John 3:16–17. MONDAY MOVIE: Watch “God Loves His Children | Now You Know.” TUESDAY TALK: :Study Elder Gerrit W. Gong’s talk, “Hosanna and Hallelujah—The Living Jesus Christ The Heart of Restoration and Easter.” WEDNESDAY WORSHIP: Listen to Calee Reed and Stephen Nelson perform “This Is the Christ.” THURSDAY TIME TO MEMORIZE: Take some time to memorize this week’s paragraph. Fill-in-the-blank guides and tips can be found at ldsliving.com/proclamation. FRIDAY FEELINGS: Record what it means to you that Christ is your Savior, Exemplar, and Redeemer. SATURDAY SHARE: Share your testimony of Jesus Christ with a loved one. AUGUST 9–15 Two hundred years ago, on a beautiful spring morning in 1820, young Joseph Smith, seeking to know which church to join, went into the woods to pray near his home in upstate New York, USA. He had questions regarding the salvation of his soul and trusted that God would direct him. SUNDAY SCRIPTURE: Read and ponder Joseph Smith—History 1:5–14. MONDAY MOVIE: Watch “The Hope of God’s Light.” TUESDAY TALK: Study President Henry B. -

Joseph Smith and Diabolism in Early Mormonism 1815-1831

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 5-2021 "He Beheld the Prince of Darkness": Joseph Smith and Diabolism in Early Mormonism 1815-1831 Steven R. Hepworth Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd Part of the History of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Hepworth, Steven R., ""He Beheld the Prince of Darkness": Joseph Smith and Diabolism in Early Mormonism 1815-1831" (2021). All Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 8062. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd/8062 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. "HE BEHELD THE PRINCE OF DARKNESS": JOSEPH SMITH AND DIABOLISM IN EARLY MORMONISM 1815-1831 by Steven R. Hepworth A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in History Approved: Patrick Mason, Ph.D. Kyle Bulthuis, Ph.D. Major Professor Committee Member Harrison Kleiner, Ph.D. D. Richard Cutler, Ph.D. Committee Member Interim Vice Provost of Graduate Studies UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY Logan, Utah 2021 ii Copyright © 2021 Steven R. Hepworth All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT “He Beheld the Prince of Darkness”: Joseph Smith and Diabolism in Early Mormonism 1815-1831 by Steven R. Hepworth, Master of Arts Utah State University, 2021 Major Professor: Dr. Patrick Mason Department: History Joseph Smith published his first known recorded history in the preface to the 1830 edition of the Book of Mormon. -

Hard Questions and Keeping the Faith

HARD QUESTIONS AND KEEPING THE FAITH by Michael R. Ash As Bill prepared an Elder’s Quorum lesson, he vaguely While the foregoing story is fictional, it is nonetheless recalled a quote from a past general conference, which, he similar to the experience of at least a few members of the thought, would enhance his lesson. Not remembering the Church. Since Joseph Smith’s First Vision, there have been exact quote, nor even who said it and when, Bill turned some who have made it their goal to revile his name his to the Internet and entered a search with a couple of key work, and his legacy. And since before the Book of Mor- words and the word “Mormon.” Bill perused the various mon came from the printing press, there have been critics “hits” returned by the search engine and found that some of who have denounced it as fictional, delusional, or blasphe- the Web pages were hostile to the Church. Initially he sim- mous. Why do some people assail the Church? Should we ply ignored these pages and continued searching through respond to critics? How should we deal with hard ques- faithful Web sites. At times, however, he found it diffi- tions and accusations? Were can we find answers? cult—upon an initial glance—to distinguish some hostile Web sites versus faithful Web sites. Some hostile sites ap- peared harmless until he read a little further. One site in WHY DO SOME PEOPLE ASSAIL THE CHURCH? particular caught his attention and he began to read more During Moroni’s initial visit with Joseph, the angel told and more of the claims made by the Web site’s author. -

Joseph Smith's First Vision.Pdf

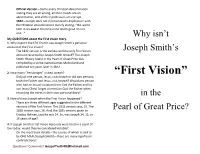

Official Version—Slams every Christian denomination stating they are all wrong, all their creeds are an abomination, and all their professors are corrupt. 1832—Joseph does not mention God’s displeasure with the Christian denominations merely stating, “the world lieth in sin and at this time none doeth good no not one...” Why isn’t My QUESTIONS about the First Vision Story: 1. Why doesn’t the LDS Church use Joseph Smith’s personal account of the First Vision? The 1832 version is the earliest and the only First Vision Joseph Smith’s account recorded by Joseph Smith himself? The Joseph Smith History found in the Pearl of Great Price was compiled by a scribe named James Mulholland and published ten years later in 1842. 2. How many “Personages” visited Joseph? “First Vision” Did just one person, Jesus, visit Joseph or did two persons, both the Father and Jesus, visit Joseph? Would any person who had an actual visitation from God the Father and his son Jesus Christ forget to mention God the Father when recording the event in their own personal diary? in the 3. How old was Joseph when the First Vision happened? There are three different ages suggested in the different versions of the First Vision. The 1832 version says, 15. The 1838 version says, 16. And, the 1835 version, given to Pearl of Great Price? Erastus Holmes, says he was 14. So, was Joseph 14, 15, or 16 years of age? 4. If Joseph Smith’s First Vision Accounts were tried in a court of law today, would they be considered reliable? On the most basic details—the source of which is said -

The Wentworth Letter

BYU Studies Quarterly Volume 9 Issue 3 Article 5 7-1-1969 The Wentworth Letter Joseph Smith Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq Recommended Citation Smith, Joseph (1969) "The Wentworth Letter," BYU Studies Quarterly: Vol. 9 : Iss. 3 , Article 5. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq/vol9/iss3/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in BYU Studies Quarterly by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Smith: The Wentworth Letter THE WENTWORTH LETTER joseph smiths letter to mr john wentworth was published in the march 1 1842 issue of the times and seasons in nauvoo illinois although the whole letter runs about three full pages the rendition of the first vision events is only one half page long the prophet him- self called it a sketch a brief history the conclusion of the letter is joseph smiths statement of belief which has come to be known as the articles of faith ed Published by BYU ScholarsArchive, 1969 1 BYU Studies Quarterly, Vol. 9, Iss. 3 [1969], Art. 5 vision and saw two glorious Zgloraglor3 he b glnginin called on the lord devoutly because we heavenly ZD 1 0 who resembled each in th it b0 v r had already come into the land of this personagest1ta exactly 0 conicconie 223 great na idolatrous nation other in features and likeness surround- ed with a brilliant light which eclipsed the gelgei0 ineasure -

Primary 5 Manual

Lesson Joseph Smith Writes 36 the Articles of Faith Purpose To strengthen the children’s desire to understand and memorize the Articles of Faith. Preparation 1. Prayerfully study the Articles of Faith, located at the end of the Pearl of Great Price, and the historical account given in this lesson. Then study the lesson and decide how you want to teach the children the scriptural and historical accounts. (See “Preparing Your Lessons,” pp. vi–vii, and “Teaching the Scriptural and Historical Accounts,” pp. vii–ix.) 2. Select the discussion questions and enrichment activities that will involve the children and best help them achieve the purpose of the lesson. 3. Materials needed: a. A Pearl of Great Price for each child. b. Articles of Faith charts from the meetinghouse library (65001–65013 or 65014, which contains all thirteen Articles of Faith). Suggested Lesson Development Invite a child to give the opening prayer. Attention Activity • What kind of mathematics are you studying in school? After the children respond, write the following algebra problem on the chalkboard: a2 +b2 = 25 • Why might this problem be difficult for you to solve? • Before you can do algebra problems, what do you first need to learn? Explain that before they learn how to do algebra problems, the children need to learn basic mathematical principles. Similarly, to learn and understand the gospel, we must first learn the basic principles of the gospel. Explain that the Prophet Joseph Smith wrote thirteen statements that briefly summarize some of the basic principles and beliefs of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. -

The First Vision: Key to Truth

By Elder Richard J. Maynes Of the Presidency of the Seventy The First Vision KEY TO TRUTH Let us not forget or take for granted the many precious truths we have learned from Joseph Smith’s First Vision. he Restoration of the fulness began in the United States. These reviv- of the gospel of Jesus Christ als are known by historians as part of in the latter days was foreseen the Second Great Awakening. It was Tand predicted by prophets through- through these revival meetings’ com- out history. The Restoration, therefore, peting notions of salvation that Joseph should not come as a surprise to those Smith and his family navigated their who study the scriptures. Dozens of religious commitment. prophetic statements throughout the Joseph was greatly influenced by Old Testament, the New Testament, and the teachings and discussions of his the Book of Mormon clearly predict father, who searched for but could not and point toward the Restoration of find among the revivalist sects any that the gospel.1 were organized like the ancient order BY WALTER RANE BY WALTER In the late 1790s, approximately of Jesus Christ and His Apostles. Joseph 2,400 years after King Nebuchadnezzar would listen and ponder during family saw in a dream that “the God of heaven Bible study. By the age of 12, he began [shall] set up a kingdom, which shall to worry about his sins and the welfare never be destroyed” (Daniel 2:44), a of his immortal soul, which led him to JOSEPH SMITH WITH FATHER AND SON, JOSEPH SMITH WITH FATHER decades-long series of religious revivals search the scriptures for himself. -

Joseph Smith and the Structure of Mormon Identity

JOSEPH SMITH AND THE STRUCTURE OF MORMON IDENTITY STEVEN L. OLSEN IN 1838, JOSEPH SMITH reduced to written form the sacred experience which led him to establish Mormonism.1 This narrative relates a series of heavenly visitations which Smith said had begun eighteen years earlier and had con- tinued until 1829. Although Smith drafted earlier and later accounts of these events, only the 1838 version has been officially recognized by the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Smith commenced his official History of the Church with this narrative. It also appeared in an 1851 collection of sacred and inspirational writings published by the Church in the British Isles. The permanent status of this text in Mormonism was secured in 1880 by its canonization at the hand of John Taylor who had recently succeeded Brigham Young to the Mormon Presidency. Since its canonization, the "Joseph Smith story," as it is known among Mormons, has become a primary document for the explication of Mormon doctrine and the introduction for many proselytes to the Church. The text has come to demand the loyalty of orthodox Mormons and has become one of Mormonism's most sacred texts. Remarkable is the contrast between the official status of the 1838 version and the general neglect by the Church of the other accounts. This difference in status cannot be explained by the historical accuracy of the respective accounts. Despite some serious challenges to the chronology of the official account, Mormons have firmly defended its historicity, even though several of the non-canonized versions do not suffer from these perceived historical inaccuracies.2 Neither can this distinction be demonstrated by the degree of complementarity of the different versions. -

Doctrine and Covenants Student Manual Religion 324 and 325

Doctrine and Covenants Student Manual Religion 324 and 325 Prepared by the Church Educational System Published by The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints Salt Lake City, Utah Send comments and corrections, including typographic errors, to CES Editing, 50 E. North Temple Street, Floor 8, Salt Lake City, UT 84150-2722 USA. E-mail: <[email protected]> Second edition © 1981, 2001 by Intellectual Reserve, Inc. All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America English approval: 4/02 Table of Contents Preface . vii Section 21 Maps . viii “His Word Ye Shall Receive, As If from Mine Own Mouth” . 43 Introduction The Doctrine and Covenants: Section 22 The Voice of the Lord to All Men . 1 Baptism: A New and Everlasting Covenant . 46 Section 1 The Lord’s Preface: “The Voice Section 23 of Warning”. 3 “Strengthen the Church Continually”. 47 Section 2 Section 24 “The Promises Made to the Fathers” . 6 “Declare My Gospel As with the Voice of a Trump” . 48 Section 3 “The Works and the Designs . of Section 25 God Cannot Be Frustrated” . 9 “An Elect Lady” . 50 Section 4 Section 26 “O Ye That Embark in the Service The Law of Common Consent . 54 of God” . 11 Section 27 Section 5 “When Ye Partake of the Sacrament” . 55 The Testimony of Three Witnesses . 12 Section 28 Section 6 “Thou Shalt Not Command Him Who The Arrival of Oliver Cowdery . 14 Is at Thy Head”. 57 Section 7 Section 29 John the Revelator . 17 Prepare against the Day of Tribulation . 59 Section 8 Section 30 The Spirit of Revelation . -

FAMILY RECORDINGS of NAUVOO 1845 and Before Including Minutes of the First LDS Family Gathering

FAMILY RECORDINGS OF NAUVOO 1845 and Before Including Minutes of the First LDS Family Gathering * Indian Brook near the Howe Plantation Site, Hopkinton, Middx, Mass where all the children of PHINEAS HOWE and SUSANNAH GODDARD HOWE were born. See footnote page 36 and chart page 2. For their descendants: BARLOW, DECKER, ELLSWORTH, GREENE, HAVEN, HYDE, RICHARDS, ROCKWOOD, YOUNG, etc. See pages 24 and 46. This TITLE PAGE is punched to enable you to place the booklet in your lega size BOOK OF REMEMBRANCE. Extend this page and open up the booklet to the middle of the stapled pages to let it lie flat. FAMILY RECORDINGS OF NAUVOO Compiled by a third great-grandson of the Howes Ora Haven Barlow Copyright 1965 0. H. BARLOW 631 South 11th East Salt Lake City, Utah 84102 Price: $1.00 postpaid with special rates to family organizations (Jan. 1965 Printing) Stanway Printing Co. * William Elizabeth Simon Mary Samuel Elizabeth Richard Mary Goddard Miles Stone Whipple -Brigham Howe Moore Collins chr 28 Feb bal631 b a 1630 b a 1634 b 1653/4 b 1665 b 1671 b a 1666 1627 Much of Bocking Cambridge Ma'r!boro Sudbury of Middle- Engles- Bromley Essex Middlesex Middlesex Middlesex town, Mid- ham, Wilts Wilts Essex England Mass Mass Mass dlesex England England England md 1683 Conn d 1691 d 1698 d 1708 d 1720 d 1713 d 1639 d 1767 Watertown, Middx, Mass W aterton, Middx, Mass Marlboro, Middx, Mass Oxford, Worcs, Mass I I I I Edward Goddard Susannah Stone (Capt) Samuel Brigham -Abigail Moore b 24 Mar 1675 b 4 Nov 1675 b 25 Jan 1689 b 6 july 1696 Watertown, Middx, Mass -

Journal of Mormon History Vol. 14, 1988

Journal of Mormon History Volume 14 Issue 1 Article 1 1988 Journal of Mormon History Vol. 14, 1988 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/mormonhistory Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation (1988) "Journal of Mormon History Vol. 14, 1988," Journal of Mormon History: Vol. 14 : Iss. 1 , Article 1. Available at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/mormonhistory/vol14/iss1/1 This Full Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Mormon History by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Journal of Mormon History Vol. 14, 1988 Table of Contents • --The Popular History of Early Victorian Britain: A Mormon Contribution John F. C. Harrison, 3 • --Heber J. Grant's European Mission, 1903-1906 Ronald W. Walker, 17 • --The Office of Presiding Patriarch: The Primacy Problem E. Gary Smith, 35 • --In Praise of Babylon: Church Leadership at the 1851 Great Exhibition in London T. Edgar Lyon Jr., 49 • --The Ecclesiastical Position of Women in Two Mormon Trajectories Ian G Barber, 63 • --Franklin D. Richards and the British Mission Richard W. Sadler, 81 • --Synoptic Minutes of a Quarterly Conference of the Twelve Apostles: The Clawson and Lund Diaries of July 9-11, 1901 Stan Larson, 97 This full issue is available in Journal of Mormon History: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/mormonhistory/vol14/iss1/ 1 Journal of Mormon History , VOLUME 14, 1988 Editorial Staff LOWELL M. DURHAM JR., Editor ELEANOR KNOWLES, Associate Editor MARTHA SONNTAG BRADLEY, Associate Editor KENT WARE, Designer LEONARD J.