NORTHAMPTON MERCURY 1846 to 1864

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BUCKING Hal\T!SHIRE. FAR 259

TRADES DIRECTORY.] BUCKING HAl\t!SHIRE. FAR 259 Tack Thomas, The Firs, Steeple Clay- TownsendJohnEmberton,Newprt. Pagnll Webb Joseph, Mount Pleasant, ~fiddle don, Winslow Townsend J. W. Gayhurst, :Newprt. Pgnll Craydon, Steeple Claydon S.O Talbot William, The Hyde, Olney S.O Treadwell J. Winchendon Up. Aylesbury Webster Samuel, North Crawley, New- Tanner Henry, Twyford, Buckingham Treadwell Samuel, Windmill hill, Wad- port Pagnell Tapping Henry, Wendover dean, Wen- desdon, Aylesbury WeedonThomasBrown,NewHousefarm, dover, Tring Treadwell Tom, Stowe, Buckingham Chalfont St. Giles,Gerrard's Cross R.S.O TappingJ. H. Weston Turville, Aylesbury Treadwell J. jun. Tingewick, Buckingham Welch George, Gold hill, Chalfont St. Tapping John Henry, Manor farm, Stoke Tucker John, Little Totteridge, Hazle- Peter, Gerrard's Cross R.S.O Mandeville, Aylesbury mere, High Wycombe Welch T. Layter's green, Chalfont St. Tarrant J. Eton wick, Eton, Winsdor Turner W. Great Brickhill, Bletchley Peter, Gerrard's Cross R.S.O Tattam John, Deverells, Swanbrne. W nslw Turney C. T. Chicheley, K ewport Pagnell Wells J ames, Ley hill, Chesham R.S.O Tayler G. Kickles frm. Newport Pagnell Turney J. Slapton, Leighton Buzzard West Arthur, Twigside, Ibstone, Tetswrth Taylor David, Haddenham, Thame TurneyJameFJ,Soulbury,LeightonBuzzrd West GBo. Stokenchurch, Wallingford Taylor G. Little Missenden, Amersham Turnham Henry, London road, Wycombe West Geor"e, Hundridae, Chesham R.S.O Taylor Henry, Newton Blossom ville, Twidell W. Dagnall, Great Berkhamstead West Robe~t, Daws hill~Radnage, Stoken- Newport Pagnell Tyler Thomas, Loosely row, Princes church, Wallingford Taylor J. Milton Keynes, Nwprt. Pagnell Risborough S.O West W. Lewkner-up-Hill,High Wycombe Taylor James, Lane farm, Kingswood, Uff Richard, Westcott, Aylesbury Westaway Mark A. -

Premises, Sites Etc Within 30 Miles of Harrington Museum Used for Military Purposes in the 20Th Century

Premises, Sites etc within 30 miles of Harrington Museum used for Military Purposes in the 20th Century The following listing attempts to identify those premises and sites that were used for military purposes during the 20th Century. The listing is very much a works in progress document so if you are aware of any other sites or premises within 30 miles of Harrington, Northamptonshire, then we would very much appreciate receiving details of them. Similarly if you spot any errors, or have further information on those premises/sites that are listed then we would be pleased to hear from you. Please use the reporting sheets at the end of this document and send or email to the Carpetbagger Aviation Museum, Sunnyvale Farm, Harrington, Northampton, NN6 9PF, [email protected] We hope that you find this document of interest. Village/ Town Name of Location / Address Distance to Period used Use Premises Museum Abthorpe SP 646 464 34.8 km World War 2 ANTI AIRCRAFT SEARCHLIGHT BATTERY Northamptonshire The site of a World War II searchlight battery. The site is known to have had a generator and Nissen huts. It was probably constructed between 1939 and 1945 but the site had been destroyed by the time of the Defence of Britain survey. Ailsworth Manor House Cambridgeshire World War 2 HOME GUARD STORE A Company of the 2nd (Peterborough) Battalion Northamptonshire Home Guard used two rooms and a cellar for a company store at the Manor House at Ailsworth Alconbury RAF Alconbury TL 211 767 44.3 km 1938 - 1995 AIRFIELD Huntingdonshire It was previously named 'RAF Abbots Ripton' from 1938 to 9 September 1942 while under RAF Bomber Command control. -

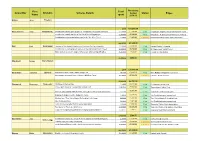

Councillor First Name Division Scheme Details Total Spent Status

First Total Remaining Councillor Division Scheme Details budget Status Payee Name spent 2009-10 Bailey John Finedon £0.00 £10,000.00 Beardsworth Sally Kingsthorpe Contribution towards play equipment - Kingsthorpe Play Builders Project £2,500.00 £7,500.00 Paid Kingsthorpe Neighbourhood Management Board Contribution towards the hire of the YMCA Bus in Kingsthorpe £1,500.00 £6,000.00 Paid Kingsthorpe Neighbourhood Management Board Contribution to design & printing costs for the 'We Were There' £100.00 £5,900.00 In progress Northamptonshire Black History Association £4,100.00 £5,900.00 Bell Paul Swanspool Opening of the Daylight Centre over Christmas for the vulnerable £1,500.00 £8,500.00 Paid Daylight Centre Fellowship Contribution to employing a p/t worker at Wellingborough Youth Project £2,800.00 £5,700.00 Paid Wellingborough Youth Project Motor skills develoment equipment for people with learning difficulties £5,250.00 £450.00 Paid Friends of Friars School £9,550.00 £450.00 Blackwell George Earls Barton £0.00 £10,000.00 Boardman Catherine Uplands New kitchen floor - West Haddon Village Hall £803.85 £9,196.15 Paid West Haddon Village Hall Committee New garage doors and locks - Lilbourne Mini Bus Garage £3,104.65 £6,091.50 In progress Lilbourne Parish Council £3,908.50 £6,091.50 Bromwich Rosemary Towcester A5 Rangers Cycling Club £759.00 £9,241.00 Paid A5 Rangers Cycling Club Cricket pitch cover for Towcestrians Cricket Club £1,845.00 £7,396.00 Paid Towcestrians Cricket Club £6,861.00 Home & away playing shirts for Towcester Ladies Hockey -

A Guide for Hirers of Milton Malsor Village Hall

WELCOME PACK A Guide for Hirers of Milton Malsor Village Hall Page 1 of 4 31/03/2013 Facilities & Utilities Entrance door, security and emergency Exit • A single door key operates all the locks fitted to the main entrance door & the door from the kitchen to the outside lobby. • Outside security lights are in operation in the car park and at the emergency exit door. • Power failure lights are in operation in the main hall, entrance hall and by the emergency exit door and ladies toilet area. Main hall (14.25m x 8.75m approx.) The maximum capacity allowed is 90 people. Sufficient chairs and tables for all to be seated are included in the hire charges. Features of the hall include: A large pull down projection screen. • A table store room to the left contains 20 x 1.52m x .76m tables and 3 smaller tables - if the tables are used please clean them before stacking away neatly. • Chair store room to the right. • On the near side is a hatchway & doorway leading to the kitchen. • Other doorways are for private use. The James meeting room (4.5m x 2.8m approx.) The room can accommodate 15 persons seated around 4 Tables. One wall is coated for use as a projection screen and a projector can be hired at extra cost; please advise the booking officer if you wish to hire the projector. Toilets o Gentlemen’s toilet on the left of the entrance hall. o Disabled toilets which contain a baby changing unit are also on the left of the entrance hall. -

Northamptonshire County Council

Northamptonshire County Council Please ask for: Freedom of Information Tel: 01604 368360 By Email Our ref: FR8787 Evan Howle Your ref: [email protected] Date: 3rd December 2018 Dear Mr Howle, Information Request: FR8787 Thank you for your Freedom of Information request dated 17th November 2018 which was received by us on 19th November 2018. Your request has been dealt with under the Freedom of Information Act and is detailed below in italics with our response in bold. (Please note the extract below has been taken directly from your original information request and is unedited). Our Response The Freedom of Information Team has been provided with the following information in response to your recent request on behalf of Northamptonshire County Council (NCC). I am looking into finding out about the location of pedestrian crossings in Northamptonshire County Council. Please could you provide me with the following: 1) A list of all the different pedestrian crossings within Northamptonshire County Council boundaries. Including the location of all formal crossings: Zebra, Toucan, Pegasus, Staggered Pelican/Puffin and Toucan crossings. Please see below extract from the County Council’s Traffic Signal Inventory (Junctions with pedestrian facilities are coded JC). Grid LOCATION Ref Junctions, Pelicans,etc. N'pton, Billing Road / Rushmere Rd JU 778608 N'pton, Kingsthorpe Hollow JC 752621 N'pton, Horsemarket / Marefair JC 752604 N'pton, Clare Street / Overstone Road JC 760613 Northamptonshire County Council One Angel Square -

Preliminary Report on the Archaeological Investigations at Northampton Road, Brackley, Northamptonshire

Albion Archaeology Preliminary report on the archaeological investigations at Northampton Road, Brackley, Northamptonshire Photo1: Aerial view of the Northampton Road development area from south Introduction Between June and October 2014 Albion Archaeology undertook open-area excavation in advance of mixed-use development by Albion Land plc on land off Northampton Road, Brackley. An area of c. 3ha was excavated divided into two main parts of unequal size, exposing an unenclosed middle Iron Age settlement. The main part of the settlement extended over c. 1.6ha and was in the northern excavation area, possibly continuing beyond the limit of the development area (see figure at the back of this report). It was characterised by roundhouses, ditched enclosures, post-built structures and an abundance of storage pits. Similar features were found to the south and in the southern excavation area, although these were smaller in number and occurred in a much lower density than in the main settlement area. Roundhouses Evidence for c. 20 roundhouses was identified. They were defined by pennanular gullies with E-facing entrances. The area defined by the gullies ranged from 8–15m in diameter, whilst the gullies themselves were generally shallow and only a few had been redug. The majority of the gullies are assumed to have served a drainage function with no structural slots associated with the outer walls being identified. Preliminary report on the archaeological investigations at Northampton Road, Brackley, Northants 1 (Mike Luke, Jo Barker and Iain Leslie. Albion report 2016-66) Albion Archaeology Many contained postholes which may have provided roof support or internal divisions. -

INFRASTRUCTURE SCHEDULE Transport

Schedule of Significant Proposed Changes Section 18.0 / Appendix 4 – West Northamptonshire Infrastructure Delivery Plan – Schedule Extract INFRASTRUCTURE SCHEDULE Transport Ref Growth Infrastructure Requirement Required for Delivery Broad Cost Funding Location Growth at Body Phasing Est. Sources Northampton T1 NRDA A45/M1 Northampton Growth NRDA NCC/HA 2014 £12.24m Developer Management Scheme* (see table below) start T2 Northampton North West Bypass Phase 1 (A428 to Northampton Developer 2014 £11.3m Developer (West) Grange Farm) Kings Heath start T3 Northampton North West Bypass Phase 2 (Grange Northampton NCC/ 2021 £16.3m Developer (West) Farm to A5199) (West) Developer start T4 Northampton Sandy Lane Relief Road Phase 2 Norwood Farm Developer 2016 £5.42m Developer (West) related to Upton Lodge Norwood Farm /Upton Lodge developments T5 NRDA New Bus Interchange at Northampton Wider Area NBC 2013 £10m WNDC/ Town Centre start NBC T6 NRDA New Railway Transport Interchange at Wider Area Network 2014 £30m WNDC/ Northampton Castle Station Rail start NCC T7 Northampton Kingsthorpe Corridor Improvements Northampton NCC 2010 £3.8m NCC/ (West) (West) start Developer T8 NRDA Highway and Junction Improvements to Northampton NCC 2013 £1.2m NCC/NBC/ provide access to developments in the Town Centre - Developer St John’s area. St John’s Area T9 NRDA Plough Junction Improvements Northampton St NCC 2015 £3m Grant John’s Area Funded T10 NRDA Ransome Road Nunn Mills Link Road Avon Nunn Mills NCC/ 2014 £17.6m WNDC/ Developer start Developer T11 NRDA London Road Ransome Road Junction Avon Nunn Mills NCC 2011 £2.3m WNDC/ Schedule of Significant Proposed Changes Section 18.0 / Appendix 4 – West Northamptonshire Infrastructure Delivery Plan – Schedule Extract Ref Growth Infrastructure Requirement Required for Delivery Broad Cost Funding Location Growth at Body Phasing Est. -

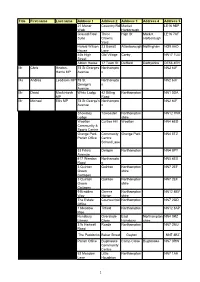

Title First Name Last Name Address 1 Address 2 Address 3 Address 4

Title First name Last name Address 1 Address 2 Address 3 Address 4 Address 5 21 Manor Coventry Rd Market LE16 9BP Walk Harborough Ground Floor Three High St Market LE16 7AF Suite Crowns Harborough Yard Harold Wilson 23 Barratt Attenborough Nottingham NG9 6AD House Lane 44b High Old Village Corby NN17 1UU Street Albion House 17 Town St Duffield Derbyshire DE56 4EH Mr Chris Heaton- 78 St Georges Northampto NN2 6JF Harris MP Avenue n Ms Andrea Leadsom MP 78 St. Northampto NN2 6JF George's n Avenue Mr David Mackintosh White Lodge 42 Billing Northampton NN1 5DA MP Road Mr Michael Ellis MP 78 St George's Northampto NN2 6JF Avenue n Showsley Towcester Northampton NN12 7NR Lodge shire Wootton Curtlee Hill Wootton NN4 6ED Community & Sports Centre Grange Park Community Grange Park NN4 5TZ Parish Office Centre School Lane 33 Friars Delapre Northampton NN4 8PY Avemue 417 Weedon Northampto NN5 4EX Road n 3 Quinton Quinton Northampton NN7 2EF Green shire Cottages 3 Quinton Quinton Northampton NN7 2EF Green shire Cottages 9 Bradden Greens Northampton NN12 8BY Way Norton shire The Estate Courteenhal Northampton NN7 2QD Office l 1 Meadow Tiffield Northampton NN12 8AP Rise Hunsbury Overslade East Northampton NN4 0RZ Library Close Hunsbury shire 31b Hartwell Roade Northampton NN7 2NU Road The Paddocks Baker Street Gayton NN7 3EZ Parish Office Bugbrooke Camp Close Bugbrooke NN7 3RW Community Centre 52 Meadow Little Northampton NN7 1AH Lane Houghton 1 Title First name Last name Address 1 Address 2 Address 3 Address 4 Address 5 Greenglades West Northampton -

South1vimlands Arc'haeology

SOUTH1VIMLANDS ARC'HAEOLOGY The Newsletter of the Council for British Archaeology, South Midlands Group (Bedfordshire, Buckinghamshire, Northamptonshire, Oxfordshire) NUIVIBER 33, 2003 CONTENTS Page Editorial Bedfordshire 1 Buckinghamshire 21 Northamptonshire 37 Oxfordshire 57 Index 113 Notes for Contributors 125 It should be noted that the reports in this volume refer, in the main, to work carried out in 2002. EDITOR: Barry Home CHAIRMAN: Ted Legg 'Beaumont' 17 Napier Street Church End Bletchley Edlesborough Milton Keynes Dunstable, Beds MK2 2NF LU6 2EP HON SEC: Vacant TREASURER: Gerry Mico 6 Rowan Close Brackley NN13 6PB Typeset by Barry Home ISSN 0960-7552 EDITORIAL Welcome to volume 33. The cumulative index to volumes 1-33, is available on the website at WWW.britarch.ac.uk/smaindex If anyone wishes to have a copy for their own PC would they please send me a 3.5" disk and a stamped addressed envelope and I will provide them with a copy. A number of new organisations have provided reports and this is very encouraging. However, some organisations continue to provide no report of their work in the area, in particular I know of one which has done work in it on a gas pipeline and a churchyard near where I live. I'm sure there are others. County archaeologists and peers must apply pressure to these defaulters. Through this editorial could I please request that when contract archaeologists do work in an area they make their presence known to the local archaeological society, because it is that society to which the public will address questions about what is going on; it does help archaeology's image if we all seem to be working together. -

Three Chimneys, 15 Blisworth Road, Gayton, Northamptonshire NN7 3HL

Three Chimneys, 15 Blisworth Road, Gayton, Northamptonshire NN7 3HL Three Chimneys, 15 Blisworth Road, Gayton, Northamptonshire NN7 3HL Guide Price: £675,000 Set in a beautiful position with far reaching views on all sides and being on the outskirts of the village of Gayton, Three Chimneys is a substantial detached period home built circa 1803. Originally two cottages and converted to one in the late 1800’s, the property was once a pub and still retains its cellar. Three Chimneys has been tastefully modernised and retains all of its character and features. Features Detached cottage Three reception rooms Three double bedrooms Fourth bedroom/Study Original features Mature gardens Far reaching views Approximately 0.36 of an acre Energy rating - E Location The pretty village of Gayton is situated about five miles south west of Northampton town centre, about two miles from the A43, Oxford Road (leading to the M40) which can be joined through the village of Blisworth. Amenities in the village include a primary school (Outstanding Ofsted report), parish church, village hall, playing fields, and a public house. The Grand Union Canal passes close by. Road communications are excellent with Junction 15A of the M1 motorway being approximately three miles distance, beyond which is the Sixfields Leisure Centre area where there is a multi-plex cinema, supermarket and restaurants. Junctions 15 & 16 of the M1 are within a ten minute drive of Gayton. Train stations can be found at Northampton (travelling time to London Euston approximately 1 hour) and Milton Keynes (travelling time to London Euston approximately 35 minutes). -

Office Investment with Development Potential

OFFICE INVESTMENT WITH DEVELOPMENT POTENTIAL GENERAL ELECTRIC, BOUGHTON ROAD, RUGBY CV21 1BU OFFICE INVESTMENT WITH DEVELOPMENT POTENTIAL GENERAL ELECTRIC, BOUGHTON ROAD, RUGBY CV21 1BU Investment Summary Opportunity to acquire a single let HQ office building with Let to GE Energy Power Conversion UK Limited, reversionary development potential a subsidiary of General Electric 3 storey office totalling86,983 sq ft sitting on a large site of 6.17 acres Potential redevelopment for residential on expiry of the lease (STP) Low site coverage of 19% Current rent of £462,000 per annum (just £5.31 psf) Excellent location 2 miles north of Rugby town centre in Offers in excess of £4,000,000 (STC) Warwickshire, off junction 1 of the M6 Net Initial Yield of 10.84% Let for a term of 5 years commencing 1st January 2018, expiring Low capital value of just £46 psf 31st December 2022 (1.93 years unexpired), and contracted out of £648,000 per acre the L&T Act 1954 OFFICE INVESTMENT WITH DEVELOPMENT POTENTIAL GENERAL ELECTRIC, BOUGHTON ROAD, RUGBY CV21 1BU Electrical Boughton Road Substation Rugby CV21 1BU TO COVENTRY TO M1 M6 M6 J1 M6 RUGBY GATEWAY CENTRAL PARK SWIFT VALLEY INDUSTRIAL ESTATE A426 GLEBE FARM INDUSTRIAL ESTATE Boughton Rd A426 CALDECOTT MANOR GE MANUFACTURING FACILITY TO RUGBY TOWN CENTRE OFFICE INVESTMENT WITH DEVELOPMENT POTENTIAL GENERAL ELECTRIC, BOUGHTON ROAD, RUGBY CV21 1BU RUGBY TOWN CENTRE GE MANUFACTURING FACILITY RUGBY Electrical Substation A426 A426 TO M6 TO RUGBY GATEWAY CALDECOTT MANOR CALDECOTT MANOR TO SWIFT VALLEY INDUSTRIAL -

Daventry Infrastructure Studies Main Report January 2009

Daventry Infrastructure Studies Main Report January 2009 www.wndc.org.uk Daventry Infrastructure Studies Main Report Limitation Copyright URS Corporation Limited (URS) has prepared this Report for West © This Report is the copyright of URS Corporation Limited. Any Northamptonshire Development Corporation (the “Client”) for unauthorised reproduction or usage by any person other than the originally intended purpose as agreed between URS and the addressee is strictly prohibited. the Client and in accordance with the Agreement under which our services were performed. No other warranty, expressed or implied, is made as to the professional advice included in this Report or any other services provided by us. For the avoidance of doubt, no party other than the Client shall have any rights attaching to, arising out of or inferred from the Report, including, without limitation, the right to rely on the Report and URS shall have no liability in relation to any use of the Report by any third party. Unless otherwise stated in this Report, the assessments made assume that the sites and facilities will continue to be used for their current purpose without significant change. The conclusions and recommendations contained in this Report are based upon information provided by others and upon the assumption that all relevant information has been provided by those parties from whom it has been requested. Information obtained from third parties has not been independently verified by URS, unless other otherwise stated in the Report. Where field investigations have been carried out, these have been restricted to a level of detail required to achieve the stated objectives of the services.