Workshop Short Course 6. WHAT WE DO NOT KNOW and PROBABLY

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Protecting & Preserving Apollo Program Lunar Landing Sites

PROTECTING & PRESERVING APOLLO PROGRAM LUNAR LANDING SITES & ARTIFACTS In accordance with the NASA TRANSITION AUTHORIZATION ACT OF 2017 Product of the OFFICE OF SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY POLICY MARCH 2018 PROTECTING & PRESERVING APOLLO PROGRAM LUNAR LANDING SITES & ARTIFACTS Background The Moon continues to hold great significance around the world. The successes of the Apollo missions still represent a profound human technological achievement almost 50 years later and continue to symbolize the pride of the only nation to send humans to an extraterrestrial body. The Apollo missions reflect the depth and scope of human imagination and the desire to push the boundaries of humankind’s existence. The Apollo landing sites and the accomplishments of our early space explorers energized our Nation's technological prowess, inspired generations of students, and greatly contributed to the worldwide scientific understanding of the Moon and our Solar System. Additionally, other countries have placed hardware on the Moon which undoubtedly has similar historic, cultural, and scientific value to their country and to humanity. Three Apollo sites remain scientifically active and all the landing sites provide the opportunity to learn about the changes associated with long-term exposure of human-created systems in the harsh lunar environment. These sites offer rich opportunities for biological, physical, and material sciences. Future visits to the Moon’s surface offer opportunities to study the effects of long-term exposure to the lunar environment on materials and articles, including food left behind, paint, nylon, rubber, and metals. Currently, very little data exist that describe what effect temperature extremes, lunar dust, micrometeoroids, solar radiation, etc. -

Spacecraft Deliberately Crashed on the Lunar Surface

A Summary of Human History on the Moon Only One of These Footprints is Protected The narrative of human history on the Moon represents the dawn of our evolution into a spacefaring species. The landing sites - hard, soft and crewed - are the ultimate example of universal human heritage; a true memorial to human ingenuity and accomplishment. They mark humankind’s greatest technological achievements, and they are the first archaeological sites with human activity that are not on Earth. We believe our cultural heritage in outer space, including our first Moonprints, deserves to be protected the same way we protect our first bipedal footsteps in Laetoli, Tanzania. Credit: John Reader/Science Photo Library Luna 2 is the first human-made object to impact our Moon. 2 September 1959: First Human Object Impacts the Moon On 12 September 1959, a rocket launched from Earth carrying a 390 kg spacecraft headed to the Moon. Luna 2 flew through space for more than 30 hours before releasing a bright orange cloud of sodium gas which both allowed scientists to track the spacecraft and provided data on the behavior of gas in space. On 14 September 1959, Luna 2 crash-landed on the Moon, as did part of the rocket that carried the spacecraft there. These were the first items humans placed on an extraterrestrial surface. Ever. Luna 2 carried a sphere, like the one pictured here, covered with medallions stamped with the emblem of the Soviet Union and the year. When Luna 2 impacted the Moon, the sphere was ejected and the medallions were scattered across the lunar Credit: Patrick Pelletier surface where they remain, undisturbed, to this day. -

Photographs Written Historical and Descriptive

CAPE CANAVERAL AIR FORCE STATION, MISSILE ASSEMBLY HAER FL-8-B BUILDING AE HAER FL-8-B (John F. Kennedy Space Center, Hanger AE) Cape Canaveral Brevard County Florida PHOTOGRAPHS WRITTEN HISTORICAL AND DESCRIPTIVE DATA HISTORIC AMERICAN ENGINEERING RECORD SOUTHEAST REGIONAL OFFICE National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior 100 Alabama St. NW Atlanta, GA 30303 HISTORIC AMERICAN ENGINEERING RECORD CAPE CANAVERAL AIR FORCE STATION, MISSILE ASSEMBLY BUILDING AE (Hangar AE) HAER NO. FL-8-B Location: Hangar Road, Cape Canaveral Air Force Station (CCAFS), Industrial Area, Brevard County, Florida. USGS Cape Canaveral, Florida, Quadrangle. Universal Transverse Mercator Coordinates: E 540610 N 3151547, Zone 17, NAD 1983. Date of Construction: 1959 Present Owner: National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) Present Use: Home to NASA’s Launch Services Program (LSP) and the Launch Vehicle Data Center (LVDC). The LVDC allows engineers to monitor telemetry data during unmanned rocket launches. Significance: Missile Assembly Building AE, commonly called Hangar AE, is nationally significant as the telemetry station for NASA KSC’s unmanned Expendable Launch Vehicle (ELV) program. Since 1961, the building has been the principal facility for monitoring telemetry communications data during ELV launches and until 1995 it processed scientifically significant ELV satellite payloads. Still in operation, Hangar AE is essential to the continuing mission and success of NASA’s unmanned rocket launch program at KSC. It is eligible for listing on the National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) under Criterion A in the area of Space Exploration as Kennedy Space Center’s (KSC) original Mission Control Center for its program of unmanned launch missions and under Criterion C as a contributing resource in the CCAFS Industrial Area Historic District. -

The Lunar Dust-Plasma Environment Is Crucial

TheThe LunarLunar DustDust --PlasmaPlasma EnvironmentEnvironment Timothy J. Stubbs 1,2 , William M. Farrell 2, Jasper S. Halekas 3, Michael R. Collier 2, Richard R. Vondrak 2, & Gregory T. Delory 3 [email protected] Lunar X-ray Observatory(LXO)/ Magnetosheath Explorer (MagEX) meeting, Hilton Garden Inn, October 25, 2007. 1 University of Maryland, Baltimore County 2 NASA Goddard Space Flight Center 3 University of California, Berkeley TheThe ApolloApollo AstronautAstronaut ExperienceExperience ofof thethe LunarLunar DustDust --PlasmaPlasma EnvironmentEnvironment “… one of the most aggravating, restricting facets of lunar surface exploration is the dust and its adherence to everything no matter what kind of material, whether it be skin, suit material, metal, no matter what it be and it’s restrictive friction-like action to everything it gets on. ” Eugene Cernan, Commander Apollo 17. EvidenceEvidence forfor DustDust AboveAbove thethe LunarLunar SurfaceSurface Horizon glow from forward scattered sunlight • Dust grains with radius of 5 – 6 m at about 10 to 30 cm from the surface, where electrostatic and gravitational forces balance. • Horizon glow ~10 7 too bright to be explained by micro-meteoroid- generated ejecta [Zook et al., 1995]. Composite image of morning and evening of local western horizon [Criswell, 1973]. DustDust ObservedObserved atat HighHigh AltitudesAltitudes fromfrom OrbitOrbit Schematic of situation consistent with Apollo 17 observations [McCoy, 1976]. Lunar dust at high altitudes (up to ~100 km). 0.1 m-scale dust present Gene Cernan sketches sporadically (~minutes). [McCoy and Criswell, 1974]. InIn --SituSitu EvidenceEvidence forfor DustDust TransportTransport Terminators Berg et al. [1976] Apollo 17 Lunar Ejecta and Meteorites (LEAM) experiment. PossiblePossible DustyDusty HorizonHorizon GlowGlow seenseen byby ClementineClementine StarStar Tracker?Tracker? Above: image of possible horizon glow above the lunar surface. -

Apollo Space Suit

APOLLO SPACE S UIT 1962–1974 Frederica, Delaware A HISTORIC MECHANICAL ENGINEERING LANDMARK SEPTEMBER 20, 2013 DelMarVa Subsection Histor y of the Apollo Space Suit This model would be used on Apollo 7 through Apollo 14 including the first lunar mission of Neil Armstrong and Buzz International Latex Corporation (ILC) was founded in Aldrin on Apollo 11. Further design improvements were made to Dover, Delaware in 1937 by Abram Nathanial Spanel. Mr. Spanel improve mobility for astronauts on Apollo 15 through 17 who was an inventor who became proficient at dipping latex material needed to sit in the lunar rovers and perform more advanced to form bathing caps and other commercial products. He became mobility exercises on the lunar surface. This suit was known as famous for ladies apparel made under the brand name of Playtex the model A7LB. A slightly modified ILC Apollo suit would also go that today is known worldwide. Throughout WWII, Spanel drove on to support the Skylab program and finally the American-Soyuz the development and manufacture of military rubberized products Test Program (ASTP) which concluded in 1975. During the entire to help our troops. In 1947, Spanel used the small group known time the Apollo suit was produced, manufacturing was performed as the Metals Division to develop military products including at both the ILC plant on Pear Street in Dover, Delaware, as well as several popular pressure helmets for the U.S. Air Force. the ILC facility in Frederica, Delaware. In 1975, the Dover facility Based upon the success of the pressure helmets, the Metals was closed and all operations were moved to the Frederica plant. -

Shoot the Moon – 1967

Video Transcript for Archival Research Catalog (ARC) Identifier 45011 Assignment: Shoot the Moon – 1967 Narrator: The assignment was specific: get photographs of the surface of the Moon that are good enough to determine whether or not it’s safe for a man to land there. But appearances can be deceiving, just as deceiving as trying to get a good picture of, well, a candy apple. Doesn’t seem to be too much of a problem, just set it up, light it, and snap the picture. Easy, quick, simple. But it can be tough. To begin with, the apple is some distance away, so you can’t get to it to just set it up, light it, and so on. To make things even more difficult, it isn’t even holding still; it’s moving around in circles. Now timing is important. You have to take your picture when the apple is nearest to you so you get the most detail and when the light that’s available is at the best angle for the photo. And even that’s not all. You are moving too, in circles. You’re both turning and circling about the apple. Now, about that assignment. As the technology of man in space was developing, it became more and more apparent that our knowledge of the Moon’s surface as a possible landing site was not sufficient. To land man safely on the Moon and get him safely off again, we had to know whether we could set up a precise enough trajectory to reach the Moon. -

NASA Symbols and Flags in the US Manned Space Program

SEPTEMBER-DECEMBER 2007 #230 THE FLAG BULLETIN THE INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF VEXILLOLOGY www.flagresearchcenter.com 225 [email protected] THE FLAG BULLETIN THE INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF VEXILLOLOGY September-December 2007 No. 230 Volume XLVI, Nos. 5-6 FLAGS IN SPACE: NASA SYMBOLS AND FLAGS IN THE U.S. MANNED SPACE PROGRAM Anne M. Platoff 143-221 COVER PICTURES 222 INDEX 223-224 The Flag Bulletin is officially recognized by the International Federation of Vexillological Associations for the publication of scholarly articles relating to vexillology Art layout for this issue by Terri Malgieri Funding for addition of color pages and binding of this combined issue was provided by the University of California, Santa Barbara Library and by the University of California Research Grants for Librarians Program. The Flag Bulletin at the time of publication was behind schedule and therefore the references in the article to dates after December 2007 reflect events that occurred after that date but before the publication of this issue in 2010. © Copyright 2007 by the Flag Research Center; all rights reserved. Postmaster: Send address changes to THE FLAG BULLETIN, 3 Edgehill Rd., Winchester, Mass. 01890 U.S.A. THE FLAG BULLETIN (ISSN 0015-3370) is published bimonthly; the annual subscription rate is $68.00. Periodicals postage paid at Winchester. www.flagresearchcenter.com www.flagresearchcenter.com 141 [email protected] ANNE M. PLATOFF (Annie) is a librarian at the University of Cali- fornia, Santa Barbara Library. From 1989-1996 she was a contrac- tor employee at NASA’s Johnson Space Center. During this time she worked as an Information Specialist for the New Initiatives Of- fice and the Exploration Programs Office, and later as a Policy Ana- lyst for the Public Affairs Office. -

The Impact of Lunar Dust on Human Exploration

The Impact of Lunar Dust on Human Exploration The Impact of Lunar Dust on Human Exploration Edited by Joel S. Levine The Impact of Lunar Dust on Human Exploration Edited by Joel S. Levine This book first published 2021 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2021 by Joel S. Levine and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-6308-1 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-6308-7 TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface ......................................................................................................... x Joel S. Levine Remembrance. Brian J. O’Brien: From the Earth to the Moon ................ xvi Rick Chappell, Jim Burch, Patricia Reiff, and Jackie Reasoner Section One: The Apollo Experience and Preparing for the Artemis Missions Chapter One ................................................................................................. 2 Measurements of Surface Moondust and Its Movement on the Apollo Missions: A Personal Journey Brian J. O’Brien Chapter Two .............................................................................................. 41 Lunar Dust and Its Impact on Human Exploration: Identifying the Problems -

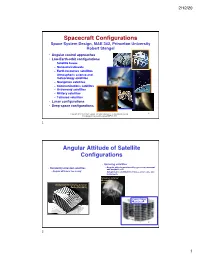

10. Spacecraft Configurations MAE 342 2016

2/12/20 Spacecraft Configurations Space System Design, MAE 342, Princeton University Robert Stengel • Angular control approaches • Low-Earth-orbit configurations – Satellite buses – Nanosats/cubesats – Earth resources satellites – Atmospheric science and meteorology satellites – Navigation satellites – Communications satellites – Astronomy satellites – Military satellites – Tethered satellites • Lunar configurations • Deep-space configurations Copyright 2016 by Robert Stengel. All rights reserved. For educational use only. 1 http://www.princeton.edu/~stengel/MAE342.html 1 Angular Attitude of Satellite Configurations • Spinning satellites – Angular attitude maintained by gyroscopic moment • Randomly oriented satellites and magnetic coil – Angular attitude is free to vary – Axisymmetric distribution of mass, solar cells, and instruments Television Infrared Observation (TIROS-7) Orbital Satellite Carrying Amateur Radio (OSCAR-1) ESSA-2 TIROS “Cartwheel” 2 2 1 2/12/20 Attitude-Controlled Satellite Configurations • Dual-spin satellites • Attitude-controlled satellites – Angular attitude maintained by gyroscopic moment and thrusters – Angular attitude maintained by 3-axis control system – Axisymmetric distribution of mass and solar cells – Non-symmetric distribution of mass, solar cells – Instruments and antennas do not spin and instruments INTELSAT-IVA NOAA-17 3 3 LADEE Bus Modules Satellite Buses Standardization of common components for a variety of missions Modular Common Spacecraft Bus Lander Congiguration 4 4 2 2/12/20 Hine et al 5 5 Evolution -

The Moon As a Laboratory for Biological Contamination Research

The Moon As a Laboratory for Biological Contamina8on Research Jason P. Dworkin1, Daniel P. Glavin1, Mark Lupisella1, David R. Williams1, Gerhard Kminek2, and John D. Rummel3 1NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, MD 20771, USA 2European Space AgenCy, Noordwijk, The Netherlands 3SETI InsQtute, Mountain View, CA 94043, USA Introduction Catalog of Lunar Artifacts Some Apollo Sites Spacecraft Landing Type Landing Date Latitude, Longitude Ref. The Moon provides a high fidelity test-bed to prepare for the Luna 2 Impact 14 September 1959 29.1 N, 0 E a Ranger 4 Impact 26 April 1962 15.5 S, 130.7 W b The microbial analysis of exploration of Mars, Europa, Enceladus, etc. Ranger 6 Impact 2 February 1964 9.39 N, 21.48 E c the Surveyor 3 camera Ranger 7 Impact 31 July 1964 10.63 S, 20.68 W c returned by Apollo 12 is Much of our knowledge of planetary protection and contamination Ranger 8 Impact 20 February 1965 2.64 N, 24.79 E c flawed. We can do better. Ranger 9 Impact 24 March 1965 12.83 S, 2.39 W c science are based on models, brief and small experiments, or Luna 5 Impact 12 May 1965 31 S, 8 W b measurements in low Earth orbit. Luna 7 Impact 7 October 1965 9 N, 49 W b Luna 8 Impact 6 December 1965 9.1 N, 63.3 W b Experiments on the Moon could be piggybacked on human Luna 9 Soft Landing 3 February 1966 7.13 N, 64.37 W b Surveyor 1 Soft Landing 2 June 1966 2.47 S, 43.34 W c exploration or use the debris from past missions to test and Luna 10 Impact Unknown (1966) Unknown d expand our current understanding to reduce the cost and/or risk Luna 11 Impact Unknown (1966) Unknown d Surveyor 2 Impact 23 September 1966 5.5 N, 12.0 W b of future missions to restricted destinations in the solar system. -

Locations of Anthropogenic Sites on the Moon R

Locations of Anthropogenic Sites on the Moon R. V. Wagner1, M. S. Robinson1, E. J. Speyerer1, and J. B. Plescia2 1Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter Camera, School of Earth and Space Exploration, Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ 85287-3603; [email protected] 2The Johns Hopkins University, Applied Physics Laboratory, Laurel, MD 20723 Abstract #2259 Introduction Methods and Accuracy Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter Camera (LROC) Narrow Angle Camera To get the location of each object, we recorded its line and sample in (NAC) images, with resolutions from 0.25-1.5 m/pixel, allow the each image it appears in, and then used USGS ISIS routines to extract identifcation of historical and present-day landers and spacecraft impact latitude and longitude for each point. The true position is calculated to be sites. Repeat observations, along with recent improvements to the the average of the positions from individual images, excluding any extreme spacecraft position model [1] and the camera pointing model [2], allow the outliers. This process used Spacecraft Position Kernels improved by LOLA precise determination of coordinates for those sites. Accurate knowledge of cross-over analysis and the GRAIL gravity model, with an uncertainty of the coordinates of spacecraft and spacecraft impact craters is critical for ±10 meters [1], and a temperature-corrected camera pointing model [2]. placing scientifc and engineering observations into their proper geologic At sites with a retrorefector in the same image as other objects (Apollo and geophysical context as well as completing the historic record of past 11, 14, and 15; Luna 17), we can improve the accuracy signifcantly. Since trips to the Moon. -

NASA's Recommendations to Space-Faring Entities: How To

National Aeronautics and Space Administration NASA’s Recommendations to Space-Faring Entities: How to Protect and Preserve the Historic and Scientific Value of U.S. Government Lunar Artifacts Release: July 20, 2011 1 National Aeronautics and Space Administration Revision and History Page Status Revision No. Description Release Date Release Baseline Initial Release 07/20/2011 Update Rev A Updated with imagery from Apollo 10/28/2011 missions 12, 14-17. Added Appendix D: Available Photo Documentation of Apollo Hardware 2 National Aeronautics and Space Administration HUMAN EXPLORATION & OPERATIONS MISSION DIRECTORATE STRATEGIC ANALYSIS AND INTEGRATION DIVISION NASA HEADQUARTERS NASA’S RECOMMENDATIONS TO SPACE-FARING ENTITIES: HOW TO PROTECT AND PRESERVE HISTORIC AND SCIENTIFIC VALUE OF U.S. GOVERNMENT ARTIFACTS THIS DOCUMENT, DATED JULY 20, 2011, CONTAINS THE NASA RECOMMENDATIONS AND ASSOCIATED RATIONALE FOR SPACECRAFT PLANNING TO VISIT U.S. HERITAGE LUNAR SITES. ORGANIZATIONS WITH COMMENTS, QUESTIONS OR SUGGESTIONS CONCERNING THIS DOCUMENT SHOULD CONTACT NASA’S HUMAN EXPLORATION & OPERATIONS DIRECTORATE, STRATEGIC ANALYSIS & INTEGRATION DIVISION, NASA HEADQUARTERS, 202.358.1570. 3 National Aeronautics and Space Administration Table of Contents REVISION AND HISTORY PAGE 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS 4 SECTION A1 – PREFACE, AUTHORITY, AND DEFINITIONS 5 PREFACE 5 DEFINITIONS 7 A1-1 DISTURBANCE 7 A1-2 APPROACH PATH 7 A1-3 DESCENT/LANDING (D/L) BOUNDARY 7 A1-4 ARTIFACT BOUNDARY (AB) 8 A1-5 VISITING VEHICLE SURFACE MOBILITY BOUNDARY (VVSMB) 8 A1-6 OVERFLIGHT