Durham E-Theses

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thoroton Society Publications

THOROTON SOCIETY Record Series Blagg, T.M. ed., Seventeenth Century Parish Register Transcripts belonging to the peculiar of Southwell, Thoroton Society Record Series, 1 (1903) Leadam, I.S. ed., The Domesday of Inclosures for Nottinghamshire. From the Returns to the Inclosure Commissioners of 1517, in the Public Record Office, Thoroton Society Record Series, 2 (1904) Phillimore, W.P.W. ed., Abstracts of the Inquisitiones Post Mortem relating to Nottinghamshire. Vol. I: Henry VII and Henry VIII, 1485 to 1546, Thoroton Society Record Series, 3 (1905) Standish, J. ed., Abstracts of the Inquisitiones Post Mortem relating to Nottinghamshire. Vol. II: Edward I and Edward II, 1279 to 1321, Thoroton Society Record Series, 4 (1914) Tate, W.E., Parliamentary Land Enclosures in the county of Nottingham during the 18th and 19th Centuries (1743-1868), Thoroton Society Record Series, 5 (1935) Blagg, T.M. ed., Abstracts of the Inquisitiones Post Mortem and other Inquisitions relating to Nottinghamshire. Vol. III: Edward II and Edward III, 1321 to 1350, Thoroton Society Record Series, 6 (1939) Hodgkinson, R.F.B., The Account Books of the Gilds of St. George and St. Mary in the church of St. Peter, Nottingham, Thoroton Society Record Series, 7 (1939) Gray, D. ed., Newstead Priory Cartulary, 1344, and other archives, Thoroton Society Record Series, 8 (1940) Young, E.; Blagg, T.M. ed., A History of Colston Bassett, Nottinghamshire, Thoroton Society Record Series, 9 (1942) Blagg, T.M. ed., Abstracts of the Bonds and Allegations for Marriage Licenses in the Archdeaconry Court of Nottingham, 1754-1770, Thoroton Society Record Series, 10 (1947) Blagg, T.M. -

Dark Romanticism in Edgar Allan Poe's the Fall of the House of Usher

KASDI MERBAH UNIVERSITY - OUARGLA Faculty of Letters and Foreign Languages Department of English Language and Literature Dissertation Academic Master Domain: Letters and Foreign Languages Speciality: Anglo-Saxon Literature Submitted by: GABANI Yassine Title: Dark Romanticism in Edgar Allan Poe’s The Fall of The House of Usher Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Master Degree in Anglo-Saxon Literature Publically defended On: 24/05/2017 Before the Jury: Mrs. Hanafi (Tidjani) Hind President KMU-Ouargla Dr. Bousbai Abdelaziz Supervisor KMU-Ouargla Mrs. Bahri Fouzia Examiner KMU-Ouargla Academic year: 2016/2017 Dedication I dedicate this work to my dear parents for their unlimited love, faith and support, I will not get to this point of my life without them. To my beloved brothers and sisters for encouraging and pushing me forward in every obstacle. To all my friends and colleagues who stood beside me in good and hard times. I Acknowledgements First of all, the greatest gratitude goes ahead to Allah who helped me to complete this study. Then, unique recognition should go to my supervisor Dr. Bousbai Abdelaziz for his great guidance, observations, and commentary and for his advice and expertise which he provided; for his generosity and help, especially for being patient with me in preparing the present work. I would like to express my heartfelt thanks to the board of examiners for proofreading and examining my paper. Finally, I would like to express my thanks to all teachers of English Department for their advice and devotion in teaching us. II Abstract The dark romantic movement is a turning point in the American literature with its characteristics that influenced many American writers. -

WORDSWORTH's GOTHIC POETICS by ROBERT J. LANG a Thesis

WORDSWORTH’S GOTHIC POETICS BY ROBERT J. LANG A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of WAKE FOREST UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS English December 2012 Winston-Salem, North Carolina Approved By: Eric Wilson, Ph.D., Advisor Philip Kuberski, Ph.D., Chair Omaar Hena, Ph.D. TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT ....................................................................................................................... iii CHAPTER 1 ........................................................................................................................1 CHAPTER 2 ........................................................................................................................8 CHAPTER 3 ......................................................................................................................27 CHAPTER 4 ......................................................................................................................45 CONCLUSION ..................................................................................................................65 WORKS CITED ................................................................................................................70 VITA ..................................................................................................................................75 ii ABSTRACT Wordsworth’s poetry is typically seen by critics as healthy-minded, rich in themes of transcendence, synthesis, -

Analyse How Frankenstein and Blade Runner Imaginatively Portray Individuals Who Challenge the Established Values of Their Times

Analyse how Frankenstein and Blade Runner imaginatively portray individuals who challenge the established values of their times. Mary Shelley’s epistolary gothic novel Frankenstein and Ridley Scott’s 1994 seminal science fiction film Blade Runner both, despite their vastly contexts imaginatively examine the fundamental nature of what it means to be human as they challenge the established views of their times. These cautionary tales warn us of the dangers of the unethical pursuit power through scientific advancement, man’s fear of mortality and the destruction of the natural world. In Frankenstein, The Modern Prometheus Mary Shelley challenges the 19th Century view that the power of science alone will advance the quality of human existence through the character of Victor. Shelley was a key figure in Romantic literary movement and Frederic Schlegel defined Romanticism as “literature depicting emotional matter in an imaginative form” and dark Romanticism became a sub-genre known as Gothic. Victor, an archetypal Gothic character, is propelled to scientific endeavour to attain personal grandeur through sinister means. He reveals Shelly’s underlying fears as seen when he states with overwrought emotive language and personal pronouns, "I believed myself destined for some great enterprise”. He reinforces his selfish motives through high modality in the lines “Wealth was an inferior object; but what glory would attend the discovery”, emphasising his desire for immortal fame. His egotism is highlighted through verb usage when he claims grandiosely “I will pioneer a new way, explore unknown powers and unfold to the world the deepest mysteries of creation” reflecting the themes of dark Romanticism. -

The Lure of Disillusion

The Lure of Disillusion RELIGION, ROMANTICISM & THE POSTMODERN CONDITION A manuscript submitted to Palgrave Macmillan Publishers, October 2010 © James Mark Shields, 2010 SHIELDS: Lure of Disillusion [DRAFT] i The Lure of Disillusion ii SHIELDS: Lure of Disillusion [DRAFT] [half-title verso: blank page] SHIELDS: Lure of Disillusion [DRAFT] iii The Lure of Disillusion Religion, Romanticism and the Postmodern Condition James Mark Shields iv SHIELDS: Lure of Disillusion [DRAFT] Eheu! paupertina philosophia in paupertinam religionem ducit:—A hunger-bitten and idea- less philosophy naturally produces a starveling and comfortless religion. It is among the miseries of the present age that it recognizes no medium between literal and metaphorical. Faith is either to be buried in the dead letter, or its name and honors usurped by a counterfeit product of the mechanical understanding, which in the blindness of self-complacency confounds symbols with allegories. – Samuel Taylor Coleridge, The Statesman’s Manual, 1839 [R]eligious discourse can be understood in any depth only by understanding the form of life to which it belongs. What characterizes that form of life is not the expressions of belief that accompany it, but a way—a way that includes words and pictures, but is far from consisting in just words and pictures—of living one’s life, of regulating all of one’s decisions. – Hilary Putnam, Renewing Philosophy, 1992 SHIELDS: Lure of Disillusion [DRAFT] v [epigraph verso: blank page] vi SHIELDS: Lure of Disillusion [DRAFT] CONTENTS Acknowledgments ix INTRODUCTION 1 Excursus One: Romanticism—A Sense of Symbol 6 PART ONE: ROMANTICISM AND (POST-)MODERNITY 1. Romancing the Postmodern 16 The Forge and the Flame A “True” Post-Modernism The Two Faces of Romanticism Romanticism as Reality-Inscription Romantic Realism 2. -

The Dark Romanticism of Francisco De Goya

The University of Notre Dame Australia ResearchOnline@ND Theses 2018 The shadow in the light: The dark romanticism of Francisco de Goya Elizabeth Burns-Dans The University of Notre Dame Australia Follow this and additional works at: https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theses Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA Copyright Regulations 1969 WARNING The material in this communication may be subject to copyright under the Act. Any further copying or communication of this material by you may be the subject of copyright protection under the Act. Do not remove this notice. Publication Details Burns-Dans, E. (2018). The shadow in the light: The dark romanticism of Francisco de Goya (Master of Philosophy (School of Arts and Sciences)). University of Notre Dame Australia. https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theses/214 This dissertation/thesis is brought to you by ResearchOnline@ND. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of ResearchOnline@ND. For more information, please contact [email protected]. i DECLARATION I declare that this Research Project is my own account of my research and contains as its main content work which had not previously been submitted for a degree at any tertiary education institution. Elizabeth Burns-Dans 25 June 2018 This work is licenced under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International licence. i ii iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This thesis would not have been possible without the enduring support of those around me. Foremost, I would like to thank my supervisor Professor Deborah Gare for her continuous, invaluable and guiding support. -

K Eeping in T Ouch

Keeping in Touch | November 2019 | November Touch in Keeping THE CENTENARY ARRIVES Celebrating 100 years this November Keeping in Touch Contents Dean Jerry: Centenary Year Top Five 04 Bradford Cathedral Mission 06 1 Stott Hill, Cathedral Services 09 Bradford, Centenary Prayer 10 West Yorkshire, New Readers licensed 11 Mothers’ Union 12 BD1 4EH Keep on Stitching in 2020 13 Diocese of Leeds news 13 (01274) 77 77 20 EcoExtravaganza 14 [email protected] We Are The Future 16 Augustiner-Kantorei Erfurt Tour 17 Church of England News 22 Find us online: Messy Advent | Lantern Parade 23 bradfordcathedral.org Photo Gallery 24 Christmas Cards 28 StPeterBradford Singing School 35 Coffee Concert: Robert Sudall 39 BfdCathedral Bishop Nick Baines Lecture 44 Tree Planting Day 46 Mixcloud mixcloud.com/ In the Media 50 BfdCathedral What’s On: November 2019 51 Regular Events 52 Erlang bradfordcathedral. Who’s Who 54 eventbrite.com Front page photo: Philip Lickley Deadline for the December issue: Wed 27th Nov 2019. Send your content to [email protected] View an online copy at issuu.com/bfdcathedral Autumn: The seasons change here at Bradford Cathedral as Autumn makes itself known in the Close. Front Page: Scraptastic mark our Centenary with a special 100 made from recycled bottle-tops. Dean Jerry: My Top Five Centenary Events What have been your top five Well, of course, there were lots of Centenary events? I was recently other things as well: Rowan Williams, reflecting on this year and there have Bishop Nick, the Archbishop of York, been so many great moments. For Icons, The Sixteen, Bradford On what it’s worth, here are my top five, Film, John Rutter, the Conversation in no particular order. -

Lines Written a Few Miles Above Tintern Abbey, on Revisiting the Banks of the Wye During a Tour, July 13, 1798

Tintern Abbey Lines Written A Few Miles Above Tintern Abbey, On Revisiting The Banks Of The Wye During A Tour, July 13, 1798 FIVE years have passed; five summers, with the length Of five long winters! and again I hear These waters, rolling from their mountain-springs With a sweet inland murmur.1 Once again Do I behold these steep and lofty cliffs, 5 Which on a wild secluded scene impress Thoughts of more deep seclusion; and connect The landscape with the quiet of the sky. The day is come when I again repose Here, under this dark sycamore, and view 10 These plots of cottage-ground, these orchard-tufts, Which, at this season, with their unripe fruits, Among the woods and copses lose themselves, Nor, with their green and simple hue, disturb The wild green landscape. Once again I see 15 These hedge-rows, hardly hedge-rows, little lines Of sportive wood run wild; these pastoral farms Green to the very door; and wreathes of smoke Sent up, in silence, from among the trees, With some uncertain notice, as might seem, 20 Of vagrant dwellers in the houseless woods, Or of some hermit’s cave, where by his fire The hermit sits alone. Though absent long, These forms of beauty have not been to me, As is a landscape to a blind man’s eye: 25 But oft, in lonely rooms, and mid the din Of towns and cities, I have owed to them, In hours of weariness, sensations sweet, Felt in the blood, and felt along the heart, And passing even into my purer mind 30 With tranquil restoration:—feelings too Of unremembered pleasure; such, perhaps, As may have had no trivial influence On that best portion of a good man’s life; His little, nameless, unremembered acts 35 Of kindness and of love. -

RIEVAULX ABBEY and ITS SOCIAL ENVIRONMENT, 1132-1300 Emilia

RIEVAULX ABBEY AND ITS SOCIAL ENVIRONMENT, 1132-1300 Emilia Maria JAMROZIAK Submitted in Accordance with the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds School of History September 2001 The candidate confirms that the work submitted is her own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others i ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I would like to express my gratitude to my supervisor Dr Wendy Childs for her continuous help and encouragement at all stages of my research. I would also like to thank other faculty members in the School of History, in particular Professor David Palliser and Dr Graham Loud for their advice. My thanks go also to Dr Mary Swan and students of the Centre for Medieval Studies who welcomed me to the thriving community of medievalists. I would like to thank the librarians and archivists in the Brotherton Library Leeds, Bodleian Library Oxford, British Library in London and Public Record Office in Kew for their assistance. Many people outside the University of Leeds discussed several aspects of Rievaulx abbey's history with me and I would like to thank particularly Dr Janet Burton, Dr David Crouch, Professor Marsha Dutton, Professor Peter Fergusson, Dr Brian Golding, Professor Nancy Partner, Dr Benjamin Thompson and Dr David Postles as well as numerous participants of the conferences at Leeds, Canterbury, Glasgow, Nottingham and Kalamazoo, who offered their ideas and suggestions. I would like to thank my friends, Gina Hill who kindly helped me with questions about English language, Philip Shaw who helped me to draw the maps and Jacek Wallusch who helped me to create the graphs and tables. -

The Archaeological Record of the Cistercians in Ireland, 1142-1541

THE ARCHAEOLOGICAL RECORD OF THE CISTERCIANS IN IRELAND, 1142-1541 written by SIMON HAYTER October 2013 Abstract In the twelfth century the Christian Church experienced a revolution in its religious organisation and many new monastic Orders were founded. The Cistercian Order spread rapidly throughout Europe and when they arrived in Ireland they brought a new style of monasticism, land management and architecture. The Cistercian abbey had an ordered layout arranged around a cloister and their order and commonality was in sharp contrast to the informal arrangement of the earlier Irish monasteries. The Cistercian Order expected that each abbey must be self-sufficient and, wherever possible, be geographically remote. Their self-sufficiency depended on their land- holdings being divided into monastic farms, known as granges, which were managed by Cisterci and worked by agricultural labourers. This scheme of land management had been pioneered on the Continent but it was new to Ireland and the socio-economic impact on medieval Ireland was significant. Today the surviving Cistercian abbeys are attractive ruins but beyond the abbey complex and within the wider environment they are nearly invisible. Medieval monastic archaeology in Ireland, which in modern terms began in the 1950s, concentrated almost exclusively on the abbey complex. The dispersed monastic land-holdings, grange complexes and settlement patterns have been almost totally ignored. This report discusses the archaeological record produced through excavations of Cistercian sites, combined -

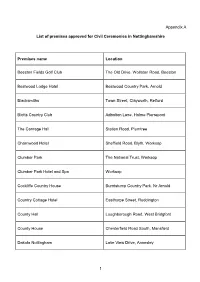

1 Appendix a List of Premises Approved for Civil Ceremonies In

Appendix A List of premises approved for Civil Ceremonies in Nottinghamshire Premises name Location Beeston Fields Golf Club The Old Drive, Wollaton Road, Beeston Bestwood Lodge Hotel Bestwood Country Park, Arnold Blacksmiths Town Street, Clayworth, Retford Blotts Country Club Adbolton Lane, Holme Pierrepont The Carriage Hall Station Road, Plumtree Charnwood Hotel Sheffield Road, Blyth, Worksop Clumber Park The National Trust, Worksop Clumber Park Hotel and Spa Worksop Cockliffe Country House Burntstump Country Park. Nr Arnold Country Cottage Hotel Easthorpe Street, Ruddington County Hall Loughborough Road, West Bridgford County House Chesterfield Road South, Mansfield Dakota Nottingham Lake View Drive, Annesley 1 Premises name Location Deincourt Hotel London Road, Newark DH Lawrence Heritage Centre (closed for bookings) Mansfield Road, Eastwood East Bridgfod Hill Kirk Hill, East Bridgford Eastwood Hall Mansfield Road, Eastwood Forever Green Restaurant Southwell Road, Mansfield The Full Moon Main Street, Morton, Southwell The Gilstrap Castle Gate, Newark Goosedale Goosedale Lane, Bestwood Village Grange Hall Vicarage Lane, Radcliffe on Trent Hodsock Priory Blyth, Nr Worksop Holme Pierrepont Hall Holme Pierrepont, Nottingham Kelham Hall Kelham, Newark Kelham House Country Manor Hotel Main Street, Kelham, Newark Langar Hall Langar, Nottinghamshire Leen Valley Golf Club Wigwam Lane, Hucknall 2 Premises name Location Lion Hotel Bridge Street, Worksop Mansfield Manor Hotel Carr Bank Park, Windmill Lane, Mansfield The Mill, Rufford Country -

Issue Number 456 February 2019 from Revd Barry Overend Valentine– the Bare Bones Valentine Was a Fourth Century Roman Soldier Destined for High Rank

Issue Number 456 February 2019 From Revd Barry Overend Valentine– the Bare Bones Valentine was a fourth century Roman soldier destined for high rank. He gave up worshipping the Roman gods once he had converted to Christianity. It was not a good career move. As soon as the Emperor OUR MISSION got wind of it, Valentine was arrested, imprisoned and subsequently A community seeking to live well with God, martyred for his new faith. That much is probably true. The rest of gathered around Jesus Christ in prayer and fellowship, Valentine’s story is long on legend, short on facts. One legend says and committed to welcome, worship and witness. that whilst in prison Valentine took a shine to the jailer’s daughter, sending her a written message – the first Valentine greeting. The Church Office Bolton Abbey, Skipton BD23 6AL Valentine was buried in Rome, but eventually his bones, or at least 01756 710238 some of them, were dug up and later turned up in France. There they [email protected] were looked after for centuries by a wealthy Roman Catholic family. Over time that family dwindled until the last surviving member no During the interregnum please address all longer wanted the responsibility of caring for ‘dem dry bones’. So enquiries to the Church Office. about 160 years ago he passed the buck, or rather the casket, to some Franciscan friars who were building a church in Glasgow. That is Website where Valentine’s bones rested until 1993. During the upheaval www.boltonpriory.church caused by renovation work on the church, the bones were kept in a cardboard box on top of a wardrobe.