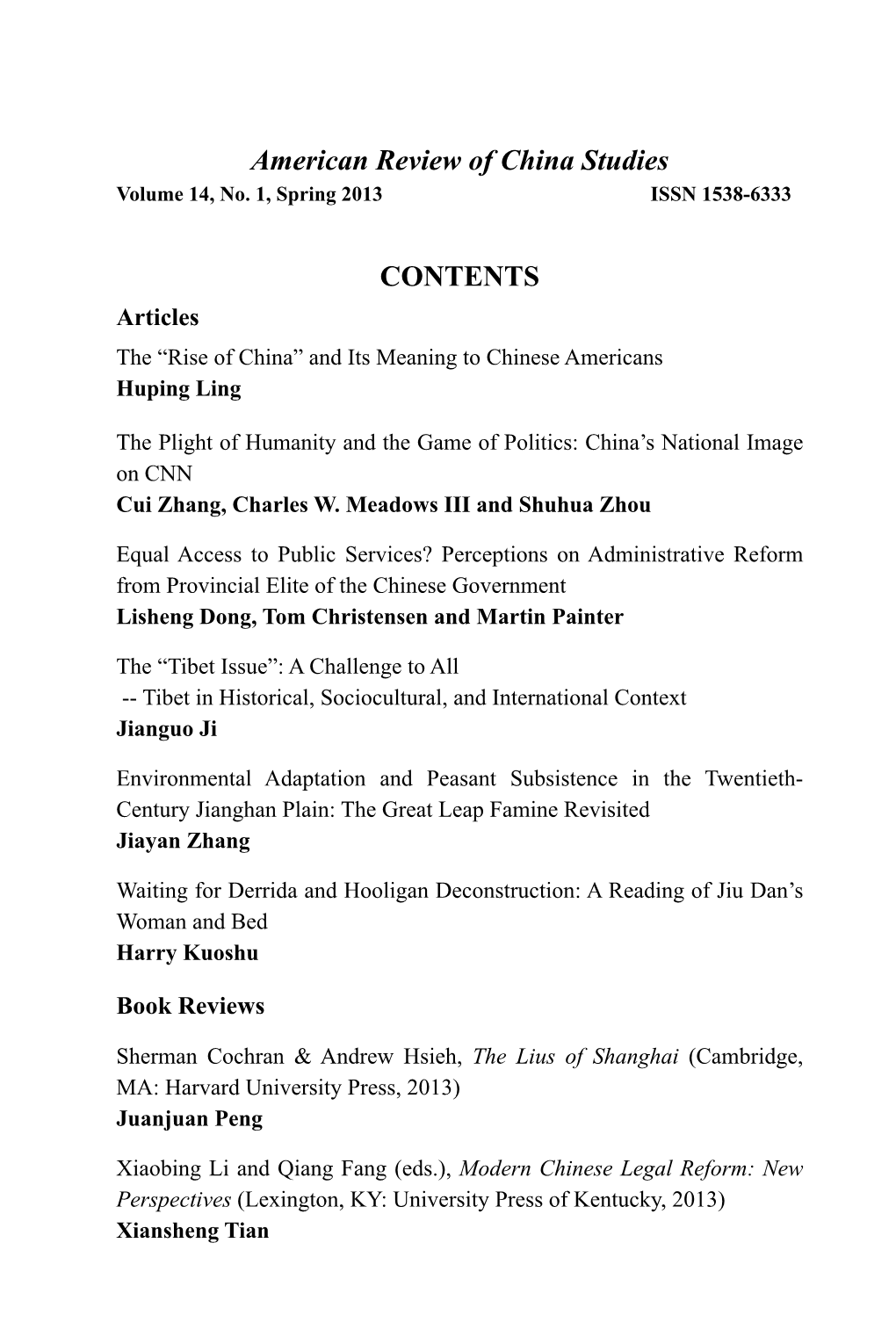

American Review of China Studies CONTENTS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CURRICULUM VITAE Min ZHOU, Ph.D

CURRICULUM VITAE Min ZHOU, Ph.D. ADDRESS Department of Sociology, UCLA 264 Haines Hall, 375 Portola Plaza, Box 951551 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1551 U.S.A. Office Phone: +1 (310) 825-3532 Email: [email protected]; home page: https://soc.ucla.edu/faculty/Zhou-Min EDUCATION May 1989 Doctor of Philosophy in Sociology, State University of New York (SUNY) at Albany May 1988 Certificate of Graduate Study in Urban Policy, SUNY-Albany December 1985 Master of Arts in Sociology, SUNY-Albany January 1982 Bachelor of Arts in English, Sun Yat-sen University (SYSU), China PHD DISSERTATION The Enclave Economy and Immigrant Incorporation in New York City’s Chinatown. UMI Dissertation Information Services, 1989. Advisor: John R. Logan, SUNY-Albany • Winner of the 1989 President’s Distinguished Doctoral Dissertation Award, SUNY-Albany PROFESSIONAL CAREER Current Positions • Distinguished Professor of Sociology and Asian American Studies, UCLA (since July 2021) • Walter and Shirley Wang Endowed Chair in U.S.-China Relations and Communications, UCLA (since 2009) • Director, UCLA Asia Pacific Center (since November 1, 2016) July 2000 to June 2021 • Professor of Sociology and Asian American Studies, UCLA • Founding Chair, Asian American Studies Department, UCLA (2004-2005; Chair of Asian American Studies Interdepartmental Degree Program (2001-2004) July 2013 to June 2016 • Tan Lark Sye Chair Professor of Sociology & Head of Division of Sociology, School of Humanities and Social Sciences, Nanyang Technological University (NTU), Singapore • Director, Chinese Heritage Centre (CHC), NTU, Singapore July 1994 to June 2000 Assistant to Associate Professor with tenure, Department of Sociology & Asian American Studies Interdepartmental Degree Program, UCLA August 1990 to July 1994 Assistant Professor of Sociology, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge M. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Migration, Social Network, and Identity

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Migration, Social Network, and Identity: The Evolution of Chinese Community in East San Gabriel Valley, 1980-2010 A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History by Yu-Ju Hung August 2013 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Clifford Trafzer, Chairperson Dr. Larry Burgess Dr. Rebecca Monte Kugel Copyright by Yu-Ju Hung 2013 The Dissertation of Yu-Ju Hung is approved: ____________________________________________ ___________________________________________ ___________________________________________ Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside Acknowledgements This dissertation would hardly have possible without the help of many friends and people. I would like to express deepest gratitude to my advisor, Professor Clifford Trafzer, who gave me boundless patience and time for my doctoral studies. His guidance and instruction not only inspired me in the dissertation research but also influenced my interests in academic pursuits. I want to thank other committee members: Professor Larry Burgess and Professor Rebecca Monte Kugel. Both of them provided thoughtful comments and valuable ideas for my dissertation. I am also indebted to Tony Yang, for his painstaking editing and proofreading work during my final writing stage. My special thanks go to Professor Chin-Yu Chen, for her constant concern and insightful suggestions for my research. I am also grateful to all people who assisted me in the process of my fieldwork: Cary Chen, Joseph Chang, Norman Hsu, David Fong, Judy Haggerty Chen, Ivy Kuan, Chuching Wang, Charles Liu, Livingstone Liu, Scarlet Treu, Chien-kuo Shieh, Champion Tang, and Sam Lo. They both served as my interviewees and informants, providing me valuable first-hand materials and access to local Chinese community. -

The Transnational World of Chinese Entrepreneurs in Chicago, 1870S to 1940S: New Sources and Perspectives on Southern Chinese Emigration

Front. Hist. China 2011, 6(3): 370–406 DOI 10.1007/s11462-011-0134-z RESEARCH ARTICLE Huping Ling The Transnational World of Chinese Entrepreneurs in Chicago, 1870s to 1940s: New Sources and Perspectives on Southern Chinese Emigration 树挪死,人挪活 A tree would likely die when transplanted; a man will survive and thrive when migrated. —Chinese proverb (author’s translation) © Higher Education Press and Springer-Verlag 2011 Abstract This article contributes to an ongoing dialogue on the causes of migration and emigration and the relationship between migrants/emigrants and their homelands by investigating historical materials dealing with the Chinese in Chicago from 1870s to 1940s. It shows that patterns of Chinese migration/ emigration overseas have endured for a long period, from pre-Qing times to today’s global capitalist expansionism. The key argument is that from the very beginning of these patterns, it has been trans-local and transnational connections that have acted as primary vehicles facilitating survival in the new land. While adjusting their lives in new environments, migrants and emigrants have made conscious efforts to maintain and renew socioeconomic and emotional ties with their homelands, thus creating transnational ethnic experiences. Keywords Chinese migration and emigration, overseas Chinese, Chinese in Chicago, Chinese ethnic businesses Introduction Just as all early civilizations used migration as an important survival strategy, so too Chinese migrated in great numbers. For example, beginning even as early as Huping Ling -

Chinese Chicago from 1893 to 1943

36 |Chinese Chicago From 1893 to 1943 Chinese Chicago from 1893 to 1943: Cultural Assimilation, Social Acceptance, and Chinese-American Identity through the Lens of Interracial Relations and Class Amy Qin With a myriad of transportation and architectural advances, Chicago grew faster than any other city in the United States at the turn of the nineteenth century, jumping to become the nation’s second largest city in 1890. Chicago emerged not only as an industrial powerhouse, but also as a multicultural hub for transplants from rural Midwestern towns, immigrants from Northern and Eastern Europe, and African Americans resettling in northern cities during the Great Migration. Those who came were, in the words of novelist Theodore Dreiser, “life-hungry for the vast energy Chicago could offer to their appetites.”1 It was also in the midst of this exciting backdrop that the frst Chinese migrants came to Chicago in the 1870s. But unlike Chinese migrants in San Francisco who experienced explicit anti-Chinese hostility, the Chinese in Chicago lived largely under the radar of the public eye, as “the average Chicagoan was no more tolerant toward Chinese than anybody else in the nation.”2 Some historians attribute this invisibility to the geographical isolation or to the small size of the Chinese population relative to other minorities, citing Chicago’s “racial diversity” in helping “the Chinese ‘disappear’ in its multiethnic ‘jungle’.”3 Between the 1890s and 1930s, however, the Chinese population in Chicago increased more than ten-fold to roughly 6,000, according to population estimates at the time. Given this rapid change in population, how much did attitudes and perceptions toward the Chinese change? Moreover, how did these new migrants, many of 1 Theodore Dreiser, Dawn: A History of Myself (1931), 159. -

Social Science Are Suitable, As Long As the Student Does Not Specialize Too Narrowly

03-05 Gen SS 221-251 9/30/03 2:04 PM Page 221 (Black plate) 2 0 3 - 5 F A C U L T Y D E G R E E S O F F E R E D DIVISION HEAD Bachelor of Arts, BA Seymour Patterson Bachelor of Science, BS PROFESSORS At Truman State University, the professional teaching C. Ray Barrow, Kathryn A. Blair, Michele Y. Breault, degree is the Masters of Arts in Education (MAE), built Patricia Burton, Robert Cummings, Michael Gary Davis, upon a strong liberal arts and sciences undergraduate Matt E. Eichor, David Gillette, Robert B. Graber, David degree. Students who wish to become teachers should con- Gruber, Randy Hagerty, Jerrold Hirsch, John Ishiyama, sult with their academic advisors as early as possible. The David Murphy, Emmanuel Nnadozie, Terry L. Olson, Paul professional preparation component of the Master’s degree Parker, Seymour Patterson, Stephen R. Pollard, James program is administered in the Division of Education. Przybylski, David Robinson, Mustafa A. Sawani, Frederic Please contact that office for further information (660-785- Shaffer, Werner Johann Sublette, Jane Sung, James L. 4383). Tichenor, Stuart Vorkink, Candy C. Young, Thomas Zoumaras UNDERGRADUATE MAJORS Economics Social ASSOCIATE PROFESSORS History Natalie Alexander, Mark Appold, William Ashcraft, Justice Systems Science Kathryn Brammall, Marijke Breuning, Bruce Coggins, Philosophy and Religion David Conner, Douglas Davenport, Martin Eisenberg, Jeff Political Science Gall, Mark Hanley, Mark Hatala, Teresa Heckert, Wolfgang Psychology Hoeschele, Ding-hwa Hsieh, Huping Ling, Judi Misale, Sociology/Anthropology Sherri Addis Palmer, Terry Palmer, Lloyd Pflueger, John Quinn, Steven Reschly, Martha Rose, Jonathan Smith, PRE-LAW PROGRAMS Robert Tigner, Sally West Preparation for a career as a lawyer really begins in col- lege. -

Asian American Pacific Islander National Historic Landmarks Theme Study National Historic Landmarks Theme Study

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior A National Historic Landmarks Theme Study ASIAN AMERICAN PACIFIC ISLANDER ISLANDER AMERICAN PACIFIC ASIAN Finding a Path Forward ASIAN AMERICAN PACIFIC ISLANDER NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARKS THEME STUDY LANDMARKS HISTORIC NATIONAL NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARKS THEME STUDY Edited by Franklin Odo Use of ISBN This is the official U.S. Government edition of this publication and is herein identified to certify its authenticity. Use of 978-0-692-92584-3 is for the U.S. Government Publishing Office editions only. The Superintendent of Documents of the U.S. Government Publishing Office requests that any reprinted edition clearly be labeled a copy of the authentic work with a new ISBN. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Odo, Franklin, editor. | National Historic Landmarks Program (U.S.), issuing body. | United States. National Park Service. Title: Finding a Path Forward, Asian American and Pacific Islander National Historic Landmarks theme study / edited by Franklin Odo. Other titles: Asian American and Pacific Islander National Historic Landmarks theme study | National historic landmark theme study. Description: Washington, D.C. : National Historic Landmarks Program, National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, 2017. | Series: A National Historic Landmarks theme study | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2017045212| ISBN 9780692925843 | ISBN 0692925848 Subjects: LCSH: National Historic Landmarks Program (U.S.) | Asian Americans--History. | Pacific Islander Americans--History. | United States--History. Classification: LCC E184.A75 F46 2017 | DDC 973/.0495--dc23 | SUDOC I 29.117:AS 4 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017045212 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. -

Curriculum Vitae

CURRICULUM VITAE WEI LI, Ph.D., Professor Asian Pacific American Studies, School of Social Transformation, and School of Geographical Science and Urban Planning; Affiliate Faculty: Center for Asian Research; Senior Sustainability Scientist, Global Institute of Sustainability, Arizona State University, Tempe AZ 85287-6403, USA Phone: (480) 727-6556 Fax: (480) 727-7911 E-mail: [email protected] Website: https://sgsup.asu.edu/wei-li EDUCATION 1991—1997 University of Southern California Doctor of Philosophy—Geography Specialization: Ethnic geography of U.S. cities; Comparative ethnicity 1982—1985 Peking University, Beijing, People’s Republic of China Master of Science—Geography Specialization: World Regional Geography; North America; Agricultural development 1978—1982 Beijing Normal College, Beijing, People’s Republic of China Bachelor of Science—Geography Specialization: Third world development; Agricultural development PROFESSIONAL POSITIONS 2015—2016 Visiting Scholar, Department of Ethnic Studies, University of CA, Berkeley 2013—2014 Faculty Head, Asian Pacific American Studies, School of Social Transformation, Arizona State University 2012 Visiting Professor, Hua Qiao (Chinese Overseas) University, Xiamen, China 2012 Visiting Professor, The International Centre for the Study of East Asian Development, Kitakyushu, Japan 2001—present Professor of Asian Pacific American Studies and Geography (2011- ); Associate Professor (2004-2011); Assistant Professor (2001-2004) Arizona State University 2009 Visiting Professor, Department of Geography, University -

Anna May Wong and Hazel Ying Lee –

ANNA MAY WONG AND HAZEL YING LEE – TWO SECOND-GENERATION CHINESE AMERICAN WOMEN IN WORLD WAR II by QIANYU SUI A THESIS Presented to the Interdisciplinary Studies Program: Asian Studies and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts June 2012 THESIS APPROVAL PAGE Student: Qianyu Sui Title: Anna May Wong and Hazel Ying Lee – Two Second-Generation Chinese American Women in World War II This thesis has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts degree in the Interdisciplinary Studies Program: Asian Studies by: Ina Asim Chair Bryna Goodman Member April Haynes Member and Kimberly Andrews Espy Vice President for Research & Innovation/Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded June 2012 ii © 2012 Qianyu Sui iii THESIS ABSTRACT Qianyu Sui Master of Arts Interdisciplinary Studies Program: Asian Studies June 2012 Title: Anna May Wong and Hazel Ying Lee – Two Second-Generation Chinese American Women in World War II Applying a historical approach which contextualizes ethnic and gender perspectives, this thesis investigates the obstacles that second-generation Chinese American women encountered as they moved into the public sphere. This included sexual restraints at home and racial harassment outside. This study examines, as well, the opportunities that stimulated these women to break from their confinements. Anna May Wong and Hazel Ying Lee will serve as two role models among this second-generation of women who successfully combined their cultural heritage with their education in the U.S. -

Curriculum Vitae

CURRICULUM VITAE WEI LI, Ph.D., Professor Associate Director of Justice, Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion School of Geographical Science and Urban Planning Asian Pacific American Studies, School of Social Transformation Affiliate Faculty: Center for Asian Research; Senior Sustainability Scientist, Julie Ann Wrigley Global Institute of Sustainability, Arizona State University, Tempe AZ 85287-6403, USA Phone: (480) 727-6556 Fax: (480) 727-7911 E-mail: [email protected] Website: https://sgsup.asu.edu/wei-li EDUCATION 1991—1997 University of Southern California Doctor of Philosophy—Geography Specialization: Ethnic geography of U.S. cities; Comparative ethnicity 1982—1985 Peking University, Beijing, People’s Republic of China Master of Science—Geography Specialization: World Regional Geography; North America; Agricultural development 1978—1982 Beijing Normal College, Beijing, People’s Republic of China Bachelor of Science—Geography Specialization: Third world development; Agricultural development PROFESSIONAL POSITIONS 2021 Spring Carroll Visiting Professor, Department of Geography, University of Oregon 2015—2016 Visiting Scholar, Department of Ethnic Studies, University of CA, Berkeley 2013—2014 Faculty Head, Asian Pacific American Studies, School of Social Transformation, Arizona State University 2012 Visiting Professor, Hua Qiao (Chinese Overseas) University, Xiamen, China 2012 Visiting Professor, The International Centre for the Study of East Asian Development, Kitakyushu, Japan 2001—present Professor of Asian Pacific American Studies and -

A History of Chinese Female Students in the United States, 1880S-1990S Author(S): Huping Ling Source: Journal of American Ethnic History, Vol

A History of Chinese Female Students in the United States, 1880s-1990s Author(s): Huping Ling Source: Journal of American Ethnic History, Vol. 16, No. 3 (Spring, 1997), pp. 81-109 Published by: University of Illinois Press on behalf of the Immigration & Ethnic History Society Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/27502196 . Accessed: 01/02/2011 20:15 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at . http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=illinois. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. University of Illinois Press and Immigration & Ethnic History Society are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Journal of American Ethnic History. -

Dear Diane‖ Letters and the Encounter of Chinese Young Women in Contemporary America

THE ―DEAR DIANE‖ LETTERS AND THE ENCOUNTER OF CHINESE YOUNG WOMEN IN CONTEMPORARY AMERICA By Copyright 2012 Hong Cai Submitted to the graduate degree program in American Studies and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ________________________________ Chairperson, David M. Katzman, Ph.D. ________________________________ Co-Chair, Cheryl B. Lester, Ph.D. ________________________________ Norman R. Yetman, Ph.D. ________________________________ William M. Tuttle, Jr., Ph.D. ________________________________ Antha Cotton-Spreckelmeyer, Ph.D. ________________________________ J.Megan Greene, Ph.D. Date Defended: June 12, 2012 The Dissertation Committee for Hong Cai certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: THE ―DEAR DIANE‖ LETTERS AND THE ENCOUNTER OF CHINESE YOUNG WOMEN IN CONTEMPORARY AMERICA ________________________________ Chairperson, David M. Katzman, Ph.D. ________________________________ Co-Chair, Cheryl B. Lester, Ph.D. Date approved: June 12, 2012 ii Abstract Focusing on the ―Dear Diane‖ advice letters, both the English and Chinese texts, this dissertation explores a group of young Chinese immigrant women as they encounter American culture as Chinese Americans were reshaped by new immigration and radical demographic changes in the 1980s. By utilizing assimilation theory as a framework for analyzing Chinese immigration, this work examines several important dimensions and aspects of young Chinese American women‘s adaptation to American life. This study also compares the ―Dear Diane‖ letters with the Jewish ―Bintel Brief‖ letters in order to explore some common characteristics of the female immigrant experience in the United States. The writer identifies a number of issues that young Chinese American women including the intensifying generational conflict and identity dislocation. -

Annualreport-2013-14.Pdf

ANNUAL REPORT July 2013 – June 2014 Prepared by The David C. Lam Institute for East-West Studies Hong Kong Baptist University September 2014 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION TO LEWI P. 3 1.1 RESEARCH FOCI P. 4 1.2 LEWI MANAGEMENT & RESEARCH TEAM P. 5 1.3 LIST OF LEWI FELLOWS P. 12 2. MAJOR ACTIVITIES 2.1 CONFERENCE P. 13 2.2 RESEARCH SEMINARS P. 14 3. PROGRAMMES 3.1 VISITING SCHOLAR PROGRAMME & VISITATIONS P. 16 3.2 RESIDENT GRADUATE SCHOLARSHIP PROGRAMME P. 21 3.3 SUMMER STUDIES PROGRAMME 3.3.1 SUMMER GLOBAL IMMERSION PROGRAMME P. 23 4. FUNDED RESEARCH PROJECTS: ON-GOING AND FUNDED OVER THE PERIOD P. 24 5. RESEARCH OUTPUTS P. 43 6. TEACHING SUPPORT / INITIATIVES P. 58 7. RETROSPECT AND PROSPECT P. 59 8. FINANCIAL REVIEW P. 62 1 Major Achievements, July 2013 - June 2014 1. Summary of major activities held: 1 major conference 15 research seminars 6 visiting scholars A summer immersion programme for Southern Methodist University 2. Grants Secured / Research Outputs by Research Staff: 8 on-going research projects 10 grants secured, 4 external (GRF) and 6 internal (HKBU), totalling HKD2,766,332 3 authored books, 3 edited books, 22 book chapters & 35 journal articles 2 1. Introduction to LEWI David C. Lam Institute for East-West Studies (LEWI or the Institute) is a consortium of 28 universities from North America, Europe and Asia. The Institute, with Hong Kong Baptist University (HKBU or the University) as the host institution, was established in 1993 with the aim to: 1) promote mutual understanding between East and West through research, academic exchange and other scholarly activities; 2) promote inter-disciplinary research in social sciences and humanities from the perspectives of both the East and the West.