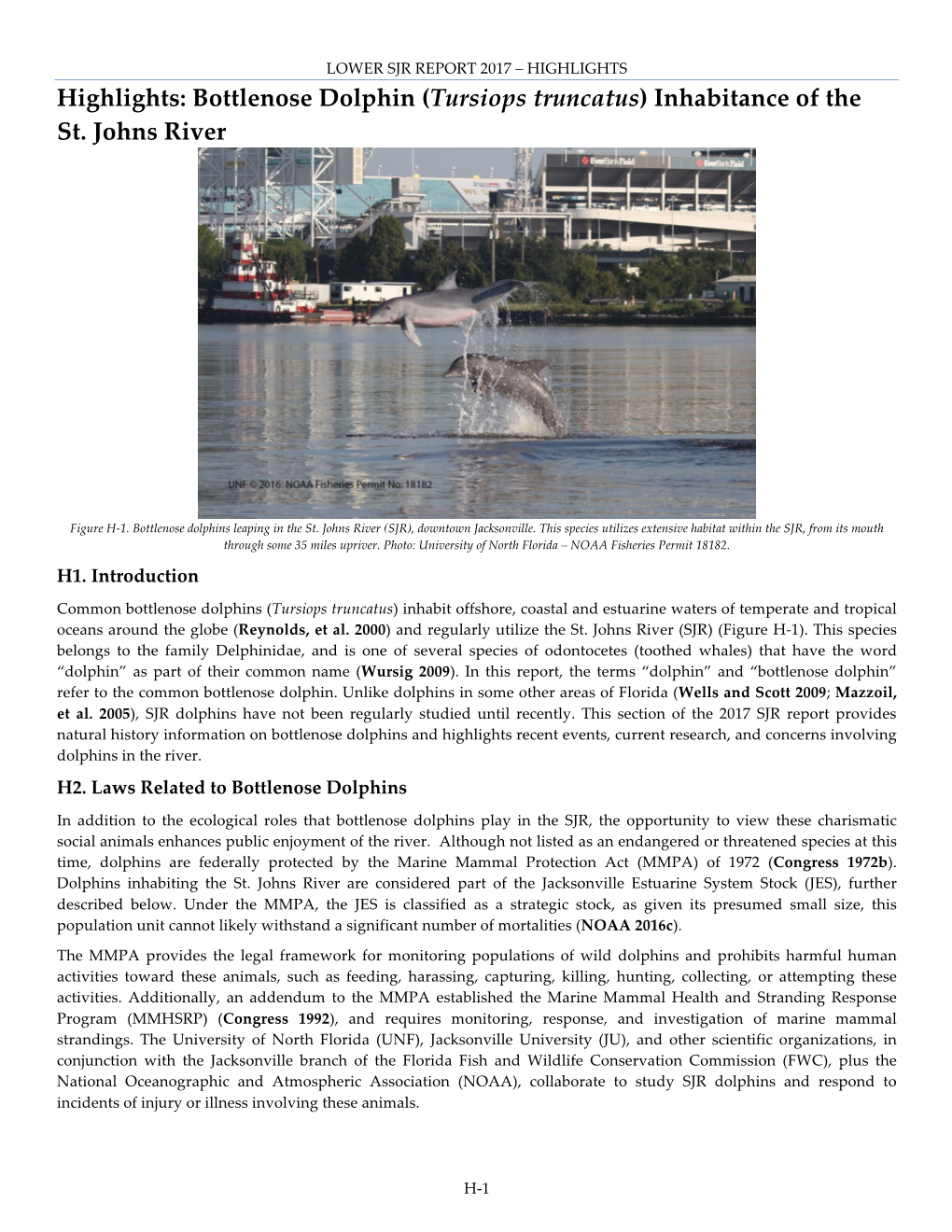

Highlights: Bottlenose Dolphin (Tursiops Truncatus) Inhabitance of the St. Johns River

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Blue-Green Algal Bloom Weekly Update Reporting March 26 - April 1, 2021

BLUE-GREEN ALGAL BLOOM WEEKLY UPDATE REPORTING MARCH 26 - APRIL 1, 2021 SUMMARY There were 12 reported site visits in the past seven days (3/26 – 4/1), with 12 samples collected. Algal bloom conditions were observed by the samplers at seven of the sites. The satellite imagery for Lake Okeechobee and the Caloosahatchee and St. Lucie estuaries from 3/30 showed low bloom potential on visible portions of Lake Okeechobee or either estuary. The best available satellite imagery for the St. Johns River from 3/26 showed no bloom potential on Lake George or visible portions of the St. Johns River; however, satellite imagery from 3/26 was heavily obscured by cloud cover. Please keep in mind that bloom potential is subject to change due to rapidly changing environmental conditions or satellite inconsistencies (i.e., wind, rain, temperature or stage). On 3/29, South Florida Water Management District staff collected a sample from the C43 Canal – S77 (Upstream). The sample was dominated by Microcystis aeruginosa and had a trace level [0.42 parts per billion (ppb)] of microcystins detected. On 3/29, Florida Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) staff collected a sample from Lake Okeechobee – S308 (Lakeside) and at the C44 Canal – S80. The Lake Okeechobee – S308 (Lakeside) sample was dominated by Microcystis aeruginosa and had a trace level (0.79 ppb) of microcystins detected. The C44 Canal – S80 sample had no dominant algal taxon and had a trace level (0.34 ppb) of microcystins detected. On 3/29, Highlands County staff collected a sample from Huckleberry Lake – Canal Entrance. -

U N S U U S E U R a C S

Ocklawaha River 301 y 316 441 CoRd E 316 E Hw Reddick CoHwy 316 PUTNAM 1 NE Jacksonville Rd Graveyard Lake Lake Kerr 95 Grass Lake Oklawaha R 108th CongressLake Healy of theCowpond Lake United States Big Lake Louise StHwy 19 VOLUSIA Eaton Cr 5 1 3 y w FLAGLER H o Mud Lake C ) Indian Lake Prarie wy s H ing pr lt S Sa 4 ( 31 wy Salt Springs Hwy StH Lake Disston Eaton Cr N Hwy 314A 0 y 4 Ormond Beach Hw Lake St Eaton Wire Rd 0 Pierson StHwy 11 4 ) 75 N F 96 Rd y d StH w R Nfs 79 C rd e (Dan F o n t Lake e r Charles S t Lake George Lake Shaw Lake Pierson Lake Jumper St Hwy 40 ( F t Brooks Rd) Cain Lake NW 22nd St ) e NW 4th Ave v A NE 17th Rd h d 40) t R 27 S (St 8 t 40 NW 20th St NE 14th R 5 wy ( wy Redwater Lake d tH StH 4 S Daytona Beach 10th St 1 NE 14th St St 0 9 P NE 25th Ave ( Little Lake Jumper S i NE 11th St StHwy 40 (Silver n Springs Blvd) t DISTRICT e 4 H Payne Creek 1 A w StHwy 40 StHwy 40 (Silver StHwy 35 3 Ch Lake Prarie v y y e SE 25th SE Springs Blvd) w Rd Ter 196 NE tH 1 7 S 9 Mill Dam ) Ocala Ave Lake Lake Winona SE 14th St StHwy 40 (Ft Brooks Rd) SE 17th St StHwy 464 Caraway Lake 40 (17th St) StHwy SE 30th SE 17th St Bear Hole Ave Wildcat Lake Astor Lake Clifton Lake Dias StHwy St Johns River 40 Halfmoon Lake Schimmerhorne Lake Little Lake Bryant Lake Bryant North Grasshopper Lake VOLUSIA MARION NF Road 599-1 DISTRICT 24 StHwy 464 (Maricamp Rd) StHwy 35 Rd)(Baseline StHwy 200 South Grasshopper Lake Wells Pond 17 441 Halford Lake De Leon Springs Marshall Chain O Swamp Lake Lake Bessiola StHwy 35 (58th Ave) Silver Farles -

St. Johns River Water Supply Impact Study (WSIS)

St. Johns River Water Supply Impact Study (WSIS) Michael G. Cullum, P.E. Chief, Bureau of Engineering & Hydro Science St. Johns River Water Management District The Water Supply Impact study is the most comprehensive and rigorous investigation of the St. Johns River ever conducted. Major Conclusions • The St. Johns River can be used as an alternative water supply source with no more than negligible or minor effects. • Future land use changes, completion of the Upper St. Johns River Basin Project, and sea level rise reduce the effects of water withdrawals. • Potential for environmental effects varies along the river’s length. • The study provides peer-reviewed tools for use by the District and others. National Academy of Sciences National Research Council (NRC) Peer Review • Three-year process working with the NRC peer review committee. • Committee consisted of nine experts. • Six multi-day meetings, field trips and numerous teleconferences. • NRC ̶ 105 page report, December 2011 NRC Concluding Comment “The overall strategy of the study and the way it was implemented were appropriate and adequate to address the goals that the District established for the WSIS.” The first step: - Understand hydrology and hydraulics and predict the changes - Resulting from potential water withdrawals. • Watershed hydrology models predict inflows into the river. • River hydrodynamic model predicts river flow, level, and salinity. Baseline Scenario • 1995 Landuse • Water Supply Planning Base Year • Good Data set 1995-2006 • Stable USJ Project Conditions • Use for Calibration of Models Forecast Scenarios • 2030 Land-Use • Complete Upper SJR Projects • Fellsmere, • C1- Sawgrass Lakes • Three Forks Marsh • Conservative Sea Level Rise (14 cm) • Withdrawal Scenarios - 77.5 mgd, 155 mgd, & 262 mgd Watershed Models • Hydrologic Simulation Program – Fortran (HSPF) – 90 separate models – 11 in-house modelers – External Peer Review • Model for Upper SJR Basin • 55 mgd - near Lake Poinsett HSPF Modeling LULCDEMSoils D.E.M.Land CoverSoils Land-use, reaches, and rainfall gauges Uppert1 St. -

U N S U U S E U R a C S

PUTNAM Legend (Ocean Shore Blvd) Halifax StHwy A1A 109th Congress of the United States River DISTRICT Lake Healy Cowpond Lake 24 Ormond-By-The-Sea Big Lake Louise DISTRICT 2 KANSAS OKLAHOMA Ormond ERIE 1 Beach Lake Disston Yonge St FLAGLER Turley C StHwy A1A (Atlantic Ave) e Holly n t e Hill r StHwy 11 40 ) S d y R t St H w d or StRd 19 Pierson (Dan F P o w Lake George e r L in Lake Shaw Lake e Pierson Justice Cain Lake S Tymber Creek Rd StHwy 430 (Mason Ave) Lpga Blvd Rd 40) Indigo Dr N (St Bill France Blvd Fort Belvoir 40 S Ridgewood Ave wy t StH H w y Ave B 5 95 A Midway Ave ( Payne Creek N Industrial Coral Sea Ave o Daytona Pkwy v Catalina Dr a Yosemite NP Lake Winona Terminal Dr R Beach d ) Midway Ave tHwy 40 Caraway Daytona Beach S Lake Williamson Blvd Shores Wildcat Lake Astor Big Tree Rd Interstate Hwy Other Major Road Lake Dias Slayton Ave Water Body 44 StHwy Lake Clifton 40 St Johns River Pine St South Other Road Schimmerhorne Lake StHwy 400 (Beville Rd) Daytona U.S. Hwy R Stream 56 Railroad i North Grasshopper Lake d g ) e e w v A o o South Grasshopper Lake n d o 92 t A 17 Rd Bay Clark w v Jolly Ford Rd la e un (D 1 Orange Rd 42 y De Leon Springs w H Chain O t 4 S Lake L i tt International Speedway Blvd Port Orange Lake Dexter le Farles Lake H T o a m Lake Daugharty w o C k r a Ponce F Lake Woodruff a r Buck Lake m Inlet s Stagger Mud Lake R d 0 2 4 6 Kilometers MARION Billies StHwy 421 (Taylor Rd) W Bay o o 0 2 4 6 Miles Tick Island d la Mud Lake nd A B l l ex v a d StHwy 19 nd e r Springs Coast Guard Station Cre Ponce de -

Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission Statewide Alligator Harvest Data Summary

FWC Home : Wildlife & Habitats : Managed Species : Alligator Management Program FLORIDA FISH AND WILDLIFE CONSERVATION COMMISSION STATEWIDE ALLIGATOR HARVEST DATA SUMMARY YEAR AVERAGE LENGTH TOTAL HARVEST FEET INCHES 2000 8 8 2,552 2001 8 8.2 2,268 2002 8 3.7 2,164 2003 8 4.6 2,830 2004 8 5.8 3,237 2005 8 4.9 3,436 2006 8 4.8 6,430 2007 8 6.7 5,942 2008 8 5.1 6,204 2009 8 0 7,844 2010 7 10.9 7,654 2011 8 1.2 8,103 Provisional data 2000 STATEWIDE ALLIGATOR HARVEST DATA SUMMARY AVERAGE LENGTH TOTAL AREA NO AREA NAME FEET INCHES HARVEST 101 LAKE PIERCE 7 9.8 12 102 LAKE MARIAN 9 9.3 30 104 LAKE HATCHINEHA 8 7.9 36 105 KISSIMMEE RIVER (POOL A) 7 6.7 17 106 KISSIMMEE RIVER (POOL C) 8 8.3 17 109 LAKE ISTOKPOGA 8 0.5 116 110 LAKE KISSIMMEE 7 11.5 172 112 TENEROC FMA 8 6.0 1 402 EVERGLADES WMA (WCAs 2A & 2B) 8 8.2 12 404 EVERGLADES WMA (WCAs 3A & 3B) 8 10.4 63 405 HOLEY LAND WMA 9 11.0 2 500 BLUE CYPRESS LAKE 8 5.6 31 501 ST. JOHNS RIVER 1 8 2.2 69 502 ST. JOHNS RIVER 2 8 0.7 152 504 ST. JOHNS RIVER 4 8 3.6 83 505 LAKE HARNEY 7 8.7 65 506 ST. JOHNS RIVER 5 9 2.2 38 508 CRESCENT LAKE 8 9.9 23 510 LAKE JESUP 9 9.5 28 518 LAKE ROUSSEAU 7 9.3 32 520 LAKE TOHOPEKALIGA 9 7.1 47 547 GUANA RIVER WMA 9 4.6 5 548 OCALA WMA 9 8.7 4 549 THREE LAKES WMA 9 9.3 4 601 LAKE OKEECHOBEE (WEST) 8 11.7 448 602 LAKE OKEECHOBEE (NORTH) 9 1.8 163 603 LAKE OKEECHOBEE (EAST) 8 6.8 38 604 LAKE OKEECHOBEE (SOUTH) 8 5.2 323 711 LAKE HANCOCK 9 3.9 101 721 RODMAN RESERVOIR 8 7.0 118 722 ORANGE LAKE 8 9.3 125 723 LOCHLOOSA LAKE 9 3.4 56 734 LAKE SEMINOLE 9 1.5 16 741 LAKE TRAFFORD -

The Shellcracker

the Shellcracker FLORIDA CHAPTER OF THE AMERICAN FISHERIES SOCIETY http://www.sdafs.org/flafs April, 2011 President’s Message: Greetings from South Florida, folks. For those of you who weren’t able to attend in January, you missed one heck of a Southern Division meeting in Tampa. With 408 attendees and over 200 individual oral and presentations, we’re still getting complements on how well it turned out. I appreciate all of the help that folks around the chapter offered, but special thanks need to be given to Eric Nagid, Linda Lombardi-Carlson, Kerry Flaherty, Andy Strickland, Wes Porak, and the rest of the planning committee for their tireless efforts to make this meeting a success. As many of you know, or perhaps are fast learning, this is a challenging time to be involved in fisheries sci- ence. Federal and state employees are both facing such issues as departmental hiring freezes, field and travel budget reductions, and an increasing individual workload. On the academic side, many colleges and universities are choosing to not back-fill positions upon retirements and are similarly increasing individual workloads on remaining faculty, not to mention the general decrease in external grant and contract funding that served in the past to support many of us and our research in graduate school. We may find our work personally fulfilling, and we often get to see things during our careers that would make many people envious, but I wish sometimes I knew where the public got its perception of the cushy life of the fisheries biologist! Now, it’s one thing to complain and yet another to offer solutions, as many of us likely heard from our parents growing up. -

Orlando New Construction & Proposed Multifamily Projects

Orlando New Construction & Proposed Multifamily Projects 4Q19 ID PROPERTY UNITS 1 Springs at Hibiscus Crossing, The 288 4 Carlton of West Melbourne, The 382 9 Aqua, The 320 Total Lease Up 990 0.0417 in 37 Addison Pointe 370 41 Oasis at West Melbourne Luxury Apartment Homes, The 316 42 Olea at Viera 166 43 Highline 171 Total Under Construction 1,023 0.25 in 161 603 Brevard 100 162 Grand Oaks 100 163 Heritage Lakes of West Melbourne 275 164 Rockledge Flats Apartment Complex 246 165 Shell Harbor 130 166 Atrium, The 149 167 San Filippo 96 168 Space Coast Town Center 600 169 Space Coast Town Center Phase II 800 Total Planned 2,496 235 Suntree 100 236 Cricket Drive 264 Total Prospective 364 2 mi Source: Yardi Matrix LEGEND Lease-Up Under Construction Planned Prospective Orlando New Construction & Proposed Multifamily Projects 4Q19 ID PROPERTY UNITS 226 Brownie Wise Mixed Use 1,700 227 Osceola Village Center 125 5 Hamilton at Lakeside, The 108 228 Parkway Crossings 384 10 Monterosso 216 229 Edgewater, The 5,000 21 San Mateo Crossing 352 Total Prospective 10,304 Total Lease Up 676 0.0417 in 24 Epoch Flora Ridge Phase I & II 448 26 Oasis at Moss Park Phase II, The 300 28 Vesta 315 Total Under Construction 1,063 0.25 in 105 Boggy Creek Crossing 306 106 Wetherbee Road 950 107 East Park Village Center 264 108 Education Village 400 109 Futura At Nona Cove 260 110 Narcoossee Cove 354 111 Weller Boulevard Multi Residential 300 137 Poinciana Estates C 100 139 Shingle Creek 212 141 Loop South 400 142 Magic Place 251 145 Mosaic @ Lake Toho 304 146 Weston -

Flood Safety and Awareness for Seminole County Residents

FLOOD SAFETY AND AWARENESS Presented by: The Seminole County Fl. (Building Division) Your property may be located in a special flood hazard area (SFHA), (incorrectly, but more commonly referred to as the 100 year Flood Plain). Your property may be high enough that it was not flooded in our most recent flood from Tropical Storm Faye. However, it can still be flooded in the future because the next event could be worse. If you are located in the floodplain, someday your property will flood. The following information contains things you should know as a resident of the unincorporated areas of Seminole County to protect yourself from flooding. 1) Seminole County Flood Hazard: Seminole County is a non-coastal community and our primary threat from wide spread flooding is caused by slow moving and/or multiple tropical storm systems occurring over a relatively short period of time. Some of the largest bodies of water that contribute to flooding in Seminole County are Lake Jesup, Lake Harney, Lake Monroe, Lake Brantley, Lake Howell, Bear Lake, Lake Mills, Lake Pickettt, the Wekiva River and the St. Johns River. Localized minor flooding may occur at any time due to our threat from brief torrential downpours in the wet summer months. The greatest threat is in the case of an unusually wet rainy season causing high water tables, saturated soils and then a tropical system in addition to that. HISTORY - Major storms and Hurricanes have caused flooding within Seminole County, most recently tropical storm Faye in 2008, the multiple storms of 2004, (Charlie, Frances and Jeanne) and Hurricane Donna in 1960. -

American Shad Habitat Plan Update

American Shad Habitat Plan Update State of Florida Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission Fish and Wildlife Research Institute Division of Marine Fisheries Management Reid Hyle [email protected] April 2021 Approved May 5, 2021 Introduction Amendment 3 to the Interstate Management Plan for Shad and River Herring cites habitat loss and degradation as major factors in the decline of and continued depression of populations of American Shad along the Atlantic coast and requires member states to develop habitat plans for American Shad in their jurisdiction. This plan is submitted to serve as the required habitat plan for the State of Florida. It outlines historic and current habitats available to American Shad in Florida and identifies known threats to those habitats as well as efforts to mitigate those threats. The primary spawning run of American shad in Florida historically was and currently is in the St. Johns River. The only other river lying within Florida in which spawning has been documented historically (Williams and Bruger 1972) and recently (Holder et al. 2011, Dutterer et al. 2011) is the Econlockhatchee River which is a tributary to the St. Johns River. The St. Marys River is along the eastern border between Georgia and Florida historically supported a population of American Shad. This plan includes these three systems. The Ocklawaha River is the largest tributary of the St. Johns River and is the largest Atlantic drainage river in Florida obstructed by a dam in its lower reaches. There is no record of a spawning run of American Shad in the Ocklawaha River pre-dating construction of the dam in 1968. -

Directions to Florida Lake Ramps

Directions to Florida Lake Ramps Alligator Chain (Alligator Lake) Alligator Chain (Trout Lake) Butler Chain Clermont Chain (Lake Minneola) Conway Chain Crooked Lake (Bob’s Landing) Crystal River (Days Inn) Eagle Lake East Lake Toho (Chisholm Park) East Lake Toho (City Ramp) East Lake Toho (East Lake Fish Camp) Everglades (Holiday Park) Harris Chain (Lake Eustis: Buzzard Beach) Harris Chain (Lake Griffin: Railroad Ramp) Harris Chain (Lake Harris: Hickory Point) Harris Chain (Lake Harris: Venetian Gardens) Harris Chain (Ocklawaha River Bridge) Holly Chain (Umatilla, Fl.) Johns Lake Lake Agnes Lake Ashby (Volusia Co.) Lake Baldwin Lake Crescent Lake Cypress Lake Deaton (Sumter Co.) Lake Diaz Lake Dorr (Follow Dirt Rd.) Lake George (Salt Springs Run) Lake Gibson Lake Istokpoga (Henderson’s Fish Camp) Lake Istokpoga (Istokpoga Park) Lake IvanhoeLake Kennedy (Cape Coral, FL.) Lake Kerr Lake Kissimmee (Camp Mack) Lake Kissimmee (Overstreet) Lake Marian Lake Marion (Bannon Fishcamp) Lake Monroe (Monroe Harbor) Lake Monroe (Wayside Park) Lake Orange/Lochloosa (Cross Creek: Marjorie Kinnan State Park) Lake Orange/Lochloosa (Lochloosa: SE 162nd Ave) Lake Orange/Lochloosa (Orange: Heagy-Burry Park) Lake Panasoffkee (Tracy’s Point F.C.) Lake Sampson/Rowell (Starke, Fl.) Lake Seminole (Wingates Lodge) Lake Stella (Crescent City) Lake Talquin (Ben Stoutamire Landing) Lake Talquin (Coes Landing) Lake Talquin (High Bluff Landing) Lake Talquin (Williams Landing) Lake Tarpon (Anderson Park) Lake Triplet (Casselberry, Fl.) Lake Underhill Lake Woodruff (Highland Park Fishcamp) Lake Yale (Marsh Park) Little Sante Fe Lake (Melrose, FL.) Rodman Reservoir (Kenwood Landing) St. Johns River (River Front Park, Palatka) St. Johns River (Ed Stone Park, Deland) St. -

Physiochemtcal Effects of the Wekiva River On

Phvsiocheniical Ejjee(,l,; oftlu: Wekiva River on the SI. Johns River. Central Florida Keellings I Physiochemtcal Effects ofthe Wekiva River on the St. Johns River, Central Florida David Keellings University (~/'Cent}4(JI Florida Introduction th The St. Johns River is a 6 order river which flows north from I its headwaters in Indian River County a distance of 310 miles to its outlet with the Atlantic Ocean in Duval County. It is a slow moving meandering river which widens into several lakes throughout its flow and has an average elevation change of less than 1 inch per mile. The St. Johns River is considered to be a blackwater river (Clewell, 1991). Blackwater rivers are characterized by tea-colored water caused by high concentrations of Dissolved Organic Matter (Meyer, 1990). The Wekiva River is a calcareous river fed by Wekiwa Spring and Rock Spring. It joins the St. Johns River as a single channel where the boundaries of Seminole, Lake, and Volusia Counties meet (Figure I). The surrounding river bank is forested with wetland species including cypress (TlLYOuiuJ11 sp.) and red maple (Ace}' I'lfhI'1IJ11) transitioning to upland oak communities through cabbage palm tSabul palmetto). This confluence of water provides an opportunity to observe the effect on water chemistry when a spring fed river joins a blackwa ter river. Physiochemical properties of water were measured at eight stations. Six of these stations were located in the St. Johns River up stream from its confluence with the Wekiva River. One station was placed in the Wekiva River upstream from its confluence with the St. -

F L O R I D a Atlantic Ocean

300 ¢ U.S. Coast Pilot 4, Chapter 9 19 SEP 2021 81°30'W 81°W 11491 Jacksonville 11490 DOCTORS LAKE ATL ANTIC OCEAN 11492 30°N Green Cove Springs 11487 Palatka CRESCENT LAKE 29°30'N Welaka Crescent City 11495 LAKE GEORGE FLORIDA LAKE WOODRUFF 29°N LAKE MONROE 11498 Sanford LAKE HARNEY Chart Coverage in Coast Pilot 4—Chapter 9 LAKE JESUP NOAA’s Online Interactive Chart Catalog has complete chart coverage http://www.charts.noaa.gov/InteractiveCatalog/nrnc.shtml 19 SEP 2021 U.S. Coast Pilot 4, Chapter 9 ¢ 301 St. Johns River (1) (8) ENCs - US5FL51M, US5FL57M, US5FL52M, US- Fish havens 5FL53M, US5FL84M, US5FL54M, US5FL56M (9) Numerous fish havens are eastward of the entrance to Charts - 11490, 11491, 11492, 11487, 11495, St. Johns River; the outermost is about 31 miles eastward 11498 of St. Johns Light. (10) (2) St. Johns River, the largest in eastern Florida, is Prominent features about 248 miles long and is an unusual major river in (11) St. Johns Light (30°23'10"N., 81°23'53"W.), 83 that it flows from south to north over most of its length. feet above the water, is shown from a white square tower It rises in the St. Johns Marshes near the Atlantic coast on the beach about 1 mile south of St. Johns River north below latitude 28°00'N., flows in a northerly direction jetty. A tower at Jacksonville Beach is prominent off and empties into the sea north of St. Johns River Light in the entrance, and water tanks are prominent along the latitude 30°24'N.