Untitled [Matthew Barlow on Sport in Canada: a History]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Continues on Page 4 the Vancouver Stealth Wish All BC Minor Lacrosse Players a Great 2018 Season!

By: LacrosseTalk Staff Fridge was a pioneer who saw that the game offered athletes new experiences in 2018 marked the 18th Annual BC High School Field Lacrosse Championships competitions and travel opportunities. as we know it. “This goes back to the high school exchanges we did with Bay Area schools like The history of BC High School Field Lacrosse dates back to the 1930’s, but the Skyline (CA) and Novato (CA) when we got introduced to Field Lacrosse by these sport didn’t really catch on until the 1960’s and 70’s. schools,” remembered Daren Fridge. “Ted saw the educational aspects and the From 1959 to the mid-1970’s, the Vancouver & District Inter High School great opportunities these programs offered -- it was a novelty.” Association offered a Field Lacrosse league. Schools played the outdoor version In the early 1980’s, schools like Rutgers University toured Western Canada of the game during a time when Box Lacrosse was the more mainstream discipline and played local clubs in Vancouver and Victoria exposing more BC talent to US most enthusiasts recognized. schools. This piqued the interest of other schools to tour BC not only to train, but Schools like Vancouver Tech, Lord Byng, Lester Pearson, Templeton, Burnaby to recruit from a relatively untapped market. North, Burnaby South, Charles Tupper, Gladstone and others competed amongst The doors truly opened for young Canadian Lacrosse players in 1986 when Hall each other. BCLA President, Sohen Gill, remembers those days well. of Famer, Bobby Allen, tipped off Syracuse Head Coach, Roy Simmons, about two “Yes, there were high school teams back then, I played for my school (North incredible lacrosse players from Victoria, brothers named Paul and Gary– and the Burnaby),” remembered Gill. -

Section Header

SECTION HEADER 2009 NLL Media Guide and Record Book 1 SECTION HEADER Follow the Entire 2010 NLL Season Live on the NLL Network at NLL.com 2010 NLL MEDIA GUIDE Table of Contents NLL Introduction Table of Contents/Staff Directory ........................1 Gait Introduction to the NLL.......................................2 2010 Division and Playoff Formats......................3 Lacrosse Talk.......................................................4 Team Information Boston Blazers .................................................5-9 Buffalo Bandits............................................10-16 Calgary Roughnecks ....................................17-22 Colorado Mammoth.....................................23-29 Edmonton Rush ...........................................30-34 Minnesota Swarm........................................35-40 Orlando Titans..............................................41-45 Philadelphia Wings......................................46-52 Rochester Knighthawks ...............................53-59 Toronto Rock................................................60-65 Washington Stealth.....................................66-71 History and Records League Award Winners and Honors .............72-73 League All-Pros............................................74-78 All-Rookie Teams ..............................................79 Individual Records/Coaching Records ...............80 National Lacrosse League All-Time Single-Season Records........................81 Staff Directory Yearly Leaders..............................................82-83 -

Continues on Page 4

By: LacrosseTalk Staff job they do interpreting the rules for athletes who play the greatest game in the If you had yin without the yang, there would be no connection…or imagine the world -- Lacrosse. Yankees without Babe Ruth; there would be no dynasty; or macaroni without the The BC Lacrosse Association is a leader in officials training with BC Lacrosse cheese…it would be just plain old pasta. Now can you imagine sports without Official Association (BCLOA) Chair Doug Wright and his team effecting change, referees? mentorship and growth in the certification programs. Wright, an avid lacrosse fan, This year, Sports Officials Canada is recognizing April 17th as National Officials grew up playing lacrosse in Richmond and began officiating in 1995, and he’s been Day. In Canada, the lacrosse community is privileged to have the best lacrosse involved ever since. His portfolio is full, managing the education and training of officials in the world. Because of that, the Canadian Lacrosse Association (CLA) some 1100 referees in BC. Wright continues his ongoing quest for excellence in has chosen not to simply observe National Officials “Day”, but rather to recognize officiating, and enjoys educating officials of all ages. April as Officials Appreciation “Month” in Lacrosse. “I take great pride in the work so many of our BCLOA volunteers are doing and Throughout April, the CLA will be featuring profiles of some of the many have done over the years,” states Wright. “Becoming a successful referee is a skill referees and umpires from across the country who continue to keep box and field as well as an art. -

Fall 2018 Issue

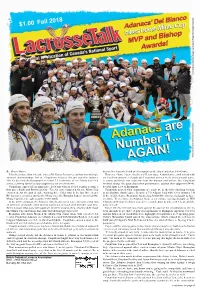

By: Owen Munro themselves from the brink of elimination on the short end of an 8-6 A’s win. It has been more than a decade since a BC Junior Lacrosse team has won multiple However, Game 3 proved to be a different story. A dominant second period with national championships, but the Coquitlam Adanacs did just that this summer. six Excelsior unanswered goals put Coquitlam on their heels in this pivotal game. The A’s defeated the Brampton Excelsiors 3-1 in the best-of-five Minto Cup final A strong pushback was expected from the maroon and yellow, but Coquitlam series, claiming Junior lacrosse supremacy for the third time. finished strong, felt good about their performance, outshot their opponent 54-46, Coquitlam capped off an impressive 2018 run with an 18-2-1 regular season, a but fell short 12-8 to Brampton. first place finish and Provincial title. The A’s have competed for the Minto Cup Coquitlam proved what champions are made of, in the title-clinching victory, every year, for the past decade, winning three titles, two in the last three years. in an absolute classic game. Despite a 7-3 Adanac lead with seven minutes left BC has not seen such a run for the Minto since the Burnaby Lakers’ stretch of five in the middle frame, Brampton stormed back with five third period goals to force Minto Cup titles in eight seasons (1998-2005). overtime. In overtime, theAdanacs broke a ten minute scoring drought as Will In the 2018 campaign, the Adanacs stifled teams on defence and turned that into Clayton and Ethan Ticehurst scored 57 seconds apart to take a 10-8 lead, and the an offensive onslaught, often putting games out of reach with multiple-goal runs. -

Handbook 2018-2019

Handbook 2018-2019 CONSTITUTION, DIRECTORY, BYLAWS, REGULATIONS, AWARDS AND HISTORY As amended to June 9, 2018 BC Hockey Handbook 2018-2019 MESSAGE FROM THE CHAIR OF THE BOARD As we continue the 100th year anniversary celebration of BC Hockey, I would first like to acknowledge the homelands and territories we share with Indigenous peoples across BC and the Yukon. It is also important that we remind ourselves of the incredible contributions of the tireless volunteers and dedicated staff whose efforts make this great game possible. The past 100 years of hockey in BC and the Yukon have left an indelible mark on the lives of all participants. Our past experiences and commitment in keeping hockey the greatest sport in Canada will continue to guide us in the future. Chair of the Board Bill Greene We will celebrate this memorable occasion with many activities planned throughout British Columbia and the Yukon. The 2019 IIHF World Junior Championship being held in Victoria and Vancouver in December 2018 and January 2019 will bring together excited participants, volunteers and hockey fans, and ‘Celly’, our recently unveiled mascot will be on the guest list as an added bonus to many scheduled events. In addition to the Road to World Junior Championship School Tour that kicks off this October and visits many communities across BC. Together there is nothing we cannot accomplish. Our goal will be to continue to implement decisions that ensure our programming is based on current data with a direct connection to the national Long Term Player Development Model. This will improve the athletic skills of our players and provide clear direction for our coaches, bench staff and officials. -

March 2009.Pdf

LacrosseTalk British Columbia Lacrosse Association March 2009 Page 3 NLL All-Star, Toronto Rock 2004 NLL Champions Cup Winner 2006 NLL All-Star Game MVP 2 x Mann Cup Winner 2004 & 2006 WLA League Scoring Title LacrosseTalk British Columbia Lacrosse Association March 2009 Page 3 ’Bellies Brighten Life for Canadian Troops nized until this time, with the aspiring lacrosse players lining up east versus west. They’ve all named themselves KAFcomrades. KAF is the air base’s designated symbol. Warrant Officer Tracy Sprague has been act- ing as the coach. Sprague is a 23-year veteran from Ottawa and this is his fifth posting to Afghanistan. He’s got a 15-year-old lacrosse- playing son who is really excited about having his father coach the team, said Brown. “Just be patient because we’re getting hit hard,” said Sprague in one of his e-mails to Brown. They’ve sent some pictures and intend to shoot some video of their games and post it on the internet. “They look young,” said Richardson. “I was shocked by the age of some of those kids.”To be able to see the game we have so much pas- sion for bringing some enjoyment to these guys that are putting their life on the line was a good way to start the new year for myself when I got that e-mail on New Year’s Day.” Contributed Photo Richardson intends to something, such as an Canadian troops in Kandahar receive lacrosse equipment as an early Christmas present armed forces night, for the troops during the Western Lacrosse Association season. -

2021 BC Lacrosse Association Voting List

2021 BC Lacrosse Association Voting List BCLA EXECUTIVE Votes Reg # Sub-Totals President 1 Past President 1 VP Operations 1 VP Performance Programs 1 VP Development 1 VP Administration and Finance 1 VP Technical Programs 1 Secretary 1 Director at Large 1 TOTAL EXECUTIVE 9 BCLCG Votes Reg # Sub-Totals Chair 1 Vice Chair - Minor 1 Vice Chair - Senior 1 Vice Chair - Field 1 Vice Chair - Women's Field 1 Secretary 1 Zone 1 Rep 1 Zone 2 Rep 1 Zone 3 Rep 1 Zone 4 Rep 1 Zone 5 Rep 1 Zone 6 Rep 1 Zone 7 Rep 1 Zone 8 Rep 1 TOTAL COACHES 14 BCLOG Votes Reg # Sub-Totals Chair 1 Director at Large 1 Vice Chair - Minor 1 Vice Chair - Senior 1 Vice Chair - Field 1 Vice Chair - Women's Field 1 Secretary 1 Zone 1 Minor 1 Zone 2 Minor 1 Zone 3 Minor 1 Zone 4 Minor 1 Zone 5 Minor 1 Zone 6 Minor 1 Zone 7 Minor 1 Zone 8 Minor 1 Lower Mainland Senior 2 Island Senior 1 South Interior Senior 1 North Interior Senior 1 Island Field 1 Lower Mainland Field 1 TOTAL OFFICIALS 22 VOLUNTEER LEADERSHIP Votes Reg # Sub-Totals Chair 1 Vice Chairs 4 Secretary 1 TOTAL VOLUNTEER LEADERSHIP 6 SENIOR BOX LACROSSE Votes Reg # Sub-Totals SENIOR DIRECTORATE Chair 1 Vice Chair 1 Secretary 1 SENIOR BOX LACROSSE Votes Reg # Sub-Totals BOX LEAGUES Western Lacrosse Association 1 West Coast Senior B 1 Prince George Senior C 1 West Central Senior C 1 Okanagan Senior C 1 Vancouver Island Senior C 1 BC Junior A 1 BC Junior B T1 1 Thompson-Okanagan Junior B T1 1 West Coast Junior B T2 1 Pacific Northwest Junior B T2 1 SENIOR BOX LACROSSE TEAMS Votes Reg # Sub-Totals TEAMS - SENIOR A Burnaby -

Continues on Page 4

By: J.P. Donville further down the road, three BC rookies have had a great start, including Canisius’ BC Lacrosse stars Kevin Crowley, Trevor Moore and Jordan McBride have all Brandon Bull (Surrey), who has 26 GB’s in eight games, Denver’s Wes Berg (New graduated from NCAA programs over the past year, but fans of BC Field Lacrosse Westminster) with 14 goals in his first ten NCAA games and Jesse King (Victoria) who might be wondering where the next group of stars will come from need not with 11 goals for Ohio State. You should expect to hear much more about this trio worry. The current crop of BC based lacrosse players in the US collegiate system in the coming years. is the largest in history and has far more depth and breadth than ever before. So Division II lacrosse has more than its fair share of BC stars, but in this division what do these latter comments mean specifically? the defensive and offensive star power is more evenly balanced. For years, BC athletes who have played in US college lacrosse programs have On the defensive side of center, Pfeiffer’s Luke Gillespie (Vancouver) has picked excelled in many facets of the game, especially goal scoring. In a sense this has not up an amazing 58 GB’s and 20 CT’s in thirteen games while Adam Bakular-Evans changed, with a large number of BC players leading their teams or conferences in (Courtenay) has been an important part of the Lake Erie story with 25 GB’s scoring. -

Traction on Demand Chooses Burnaby

2 018 Traction ON DEMAND CHOOSES BURNABY JOIN THE BURNABY’s BUILDING VALUE BBOT TODAY NEW BUSINESSES THROUGH COMMUNITY STRONG OPPORTUNITIES SEE WHY OUR COMMUNITY IS THEIR CHOICE 2018-2019 MEMBERSHIP DIRECTORY 00 | BURNABY BUSINESS DIRECTORY 2018/19 | BURNABY BOARD OF TRADE Vern Milani President Over 100 vehicles serving the milani.ca Lower Mainland Residential and Commercial Plumbing Drainage Heating Systems Air Conditioning ANNUAL BOARD 2 018 PARTNERS BUS INESS PLATINUM 8 SETTING UP CAMP BBOT takes you inside some of the recent businesses that have made Burnaby their home and explains why! GOLD 10 MEMBERSHIP BENEFITS Find out how you can protect your employees with Canada’s #1 benefit plan. The Chamber Plan is Canada’s leading group benefit plan for firms with 1-50 employees. 8 NEW HQ MOVES TO BURNABY - WHO CARES? S ILVER There has been a lot of fuss lately about cities courting big corporate headquarters to set up in their communities. We give you insight into the companies coming to Burnaby and why it matters. 16 SPEAKING OUT FOR BUSINESS Check out how the Burnaby Board of Trade develops various policy positions and advo- cates to governments at all levels on behalf of its members and the broader business community. 2018/19 BOAR D OF DIRECTORS Chair : Andrew Scott, BC International Commercial Arbitration Centre I Vice-Chair: Mike Kaerne, HollyNorth Production Supplies I Treasurer: Dirk Odenwald, ABC Recycling Ltd. Past Chair: Frank Bassett, Electronic Arts Canada Inc. I Chair, Board of Governors: Dr. Catherine Boivie, Strategic Technology Leadership Corp. Directors: Steve Carreiro, KPMG LLP I Joanne Curry, Simon Fraser University I Lee-Ann Garnett, City of Burnaby I Lara Graham, Burnaby Now Jack Kuyer, The Valley Bakery I Oskar Kwieton, Shape Properties Management Corps. -

Handbook 2009-2010

Handbook 2009-2010 CONSTITUTION, DIRECTORY, BY-LAWS, REGULATIONS, POLICIES, AWARDS AND HISTORY As amended to June 21, 2009 BC Hockey Handbook 2009-2010 PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE As we move forward towards the 2009 – 10 hockey season and the 2010 Winter Olympics in Vancouver, our sport will once again take centre stage internationally. There will be many opportunities in all communities across BC to enhance the game of hockey, but there will be many challenges, especially in the lower mainland, that will affect programming in the branch. To this end we will all need to be patient as we try to take advantage of these opportunities, while continuing to deliver quality programming and hosting our provincial championships. We will continue to use our strategic plan as a guide as we develop new Rick Boekestyn programming and introduce new initiatives President that we believe will help us service our membership. One such initiative will be the move to achieve “Speak Out!” Certification on-line. This program will be delivered through the “Respect in Sport” initiative offered through Hockey Canada’s e-learning programming. We are excited by this move and hope that you will help by being patient as we tackle any hurdles that may occur. As an Executive Committee we are in the midst of a governance review, and will continue to look at changes in governance that will help this organization be more efficient, and allow us to get the most out of our volunteers. My thanks to the Executive for their hard work in the past and future. With the help of the best staff in hockey, I look forward to working with this group we continue to work on your behalf. -

2013 SBC Team

TEAM OF THE YEAR NOMINATION Description: This award recognizes an amateur team competing in a Sport BC sanctioned league representing British Columbia Criteria: • The term “team” in this category does not refer to a group of individual competitors (such as a ski team), but rather a team in commonly known team sports (such as hockey, volleyball, lacrosse, etc...) • Nominees will be judged for their performance in 2013 only. • All-Star teams do not qualify • Member organizations may submit only one nominee in this category Submission Requirements: • Only typewritten or word-processed nominations will be accepted • Sport BC reserves the right to seek additional nominations at any time and the right to decline nominations • Fully completed nomination forms and citations must be received at Sport BC by Friday, November 15, 2013 • Please include a head and shoulders or action photo of the nominee in jpg format with a minimum of 300 pixels per inch Previous Award Recipients: 2012- Pentiction Vees Hockey 2011- Surrey United Womens Soccer 1987 - Pat Sanders Rick, Ladies Curling 2010 - UBC Womens Volleyball 1986 - UBC Thunderbirds, Football 2009 - Vernon Vipers, Hockey 1985 - Linda Moore Rink, Ladies Curling 2008 - Canadian Olympic Men’s Rowing 8 1984 - University of Victoria Vikings, Basketball 2007 - Kelly Scott’s Curling Team 1983 - Vancouver Firefighters Soccer Team 2006 - Canadian National Rowing Team Men’s Pair 1982 - UBC Thunderbirds, Football 2005 - Simon Fraser University Women’s Basketball 1981 - Janice Mason / Lisa Roy, Pairs Rowing -

NNII 1110.112 Weiß

NS. DR. iA. to5 North America's #1 Native Weekly Newspaper $1.00 Cana f Cana I n ë . A of rr r r , Library on ..r ' ri olle t rl i National Collection. i Newspaper Wellington ON I 395 ON O arahsonha kenh OnkwehonweneSix Nations of the Grant Ottawa _..ay May 12, 2004 sept 04 . J Former . Indian Affairs :.» Minister looks at Six Nations me water problems r t By Edna Gooder Staff Reporter Former Minister of Indian Affairs, Douglas Firth along with elected band council chief Roberta Jamieson toured local homes and the water treatment plant last Friday in a move to try to find out why Six Nations water is contaminated Firth told Turtle Island News, in a sentative from the Ministry of brief interview at the water treat- Indian Affairs and Northern ment plant, that he came to discuss Affairs Canada (INAC) . the quality of the Six Nations water He toured the Six Nations on with the elected band council. Friday with Roberta Jamieson repre- Douglas Firth is the special (Continued on page 3) r Local woman launches anti - r, ter . .t,a . ` . t,, . .r residency permit petition k dI , .. , y Lynda Powless N ,: 1J ^ U r ,.% 'Of Editor , - ,.i/. ' ,y For Alva Martin, a vote for' the Six Nations Band Council's proposed n , new Residency Permit Bylaw means a change in welcoming signs to Six I \1 i r Nations. 1 C , Instead of the Grand River Territory of Six Nations, she says the signs {` . r, 1- J.1ïi, f.. ' A'f will read, "welcome to the City of Six Nations.