Refocus the Films of Elaine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Neues Textdokument (2).Txt

Filmliste Liste de filme DVD Münchhaldenstrasse 10, Postfach 919, 8034 Zürich Tel: 044/ 422 38 33, Fax: 044/ 422 37 93 www.praesens.com, [email protected] Filmnr Original Titel Regie 20001 A TIME TO KILL Joel Schumacher 20002 JUMANJI 20003 LEGENDS OF THE FALL Edward Zwick 20004 MARS ATTACKS! Tim Burton 20005 MAVERICK Richard Donner 20006 OUTBREAK Wolfgang Petersen 20007 BATMAN & ROBIN Joel Schumacher 20008 CONTACT Robert Zemeckis 20009 BODYGUARD Mick Jackson 20010 COP LAND James Mangold 20011 PELICAN BRIEF,THE Alan J.Pakula 20012 KLIENT, DER Joel Schumacher 20013 ADDICTED TO LOVE Griffin Dunne 20014 ARMAGEDDON Michael Bay 20015 SPACE JAM Joe Pytka 20016 CONAIR Simon West 20017 HORSE WHISPERER,THE Robert Redford 20018 LETHAL WEAPON 4 Richard Donner 20019 LION KING 2 20020 ROCKY HORROR PICTURE SHOW Jim Sharman 20021 X‐FILES 20022 GATTACA Andrew Niccol 20023 STARSHIP TROOPERS Paul Verhoeven 20024 YOU'VE GOT MAIL Nora Ephron 20025 NET,THE Irwin Winkler 20026 RED CORNER Jon Avnet 20027 WILD WILD WEST Barry Sonnenfeld 20028 EYES WIDE SHUT Stanley Kubrick 20029 ENEMY OF THE STATE Tony Scott 20030 LIAR,LIAR/Der Dummschwätzer Tom Shadyac 20031 MATRIX Wachowski Brothers 20032 AUF DER FLUCHT Andrew Davis 20033 TRUMAN SHOW, THE Peter Weir 20034 IRON GIANT,THE 20035 OUT OF SIGHT Steven Soderbergh 20036 SOMETHING ABOUT MARY Bobby &Peter Farrelly 20037 TITANIC James Cameron 20038 RUNAWAY BRIDE Garry Marshall 20039 NOTTING HILL Roger Michell 20040 TWISTER Jan DeBont 20041 PATCH ADAMS Tom Shadyac 20042 PLEASANTVILLE Gary Ross 20043 FIGHT CLUB, THE David -

DAN LEIGH Production Designer

(3/31/17) DAN LEIGH Production Designer FILM & TELEVISION DIRECTOR COMPANIES PRODUCERS “GYPSY” Sam Taylor-Johnson Netflix Rudd Simmons (TV Series) Scott Winant Universal Television Tim Bevan “THE FAMILY” Paul McGuigan ABC David Hoberman (Pilot / Series) Mandeville Todd Lieberman “FALLING WATER” Juan Carlos Fresnadillo USA Gale Anne Hurd (Pilot) Valhalla Entertainment Blake Masters “THE SLAP” Lisa Cholodenko NBC Rudd Simmons (TV Series) Michael Morris Universal Television Ken Olin “THE OUTCASTS” Peter Hutchings BCDF Pictures Brice Dal Farra Claude Dal Farra “JOHN WICK” David Leitch Thunder Road Pictures Basil Iwanyk Chad Stahelski “TRACERS” Daniel Benmayor Temple Hill Entertainment Wyck Godfrey FilmNation Entertainment D. Scott Lumpkin “THE AMERICANS” Gavin O'Connor DreamWorks Television Graham Yost (Pilot) Darryl Frank “VAMPS” Amy Heckerling Red Hour Adam Brightman Lucky Monkey Stuart Cornfeld Molly Hassell Lauren Versel “PERSON OF INTEREST” Various Bad Robot J.J. Abrams (TV Series) CBS Johanthan Nolan Bryan Burk Margot Lulick “WARRIOR” Gavin O’Connor Lionsgate Greg O’Connor Solaris “MARGARET” Kenneth Lonergan Mirage Enterprises Gary Gilbert Fox Searchlight Sydney Pollack Scott Rudin “BRIDE WARS” Gary Winick Firm Films Alan Riche New Regency Pictures Peter Riche Julie Yorn “THE BURNING PLAIN” Guillermo Arriaga 2929 Entertainment Laurie MacDonald Walter F. Parkes SANDRA MARSH & ASSOCIATES Tel: (310) 285-0303 Fax: (310) 285-0218 e-mail: [email protected] (3/31/17) DAN LEIGH Production Designer ---2-222---- FILM & TELEVISION COMPANIES -

A LOOK BACK at WONDER WOMAN's FEMINIST (AND NOT-SO- FEMINIST) HISTORY Retour Sur L'histoire Féministe (Et Un Peu Moins Féministe) De Wonder Woman

Did you know? According to a recent media analysis, films with female stars earnt more at the box office between 2014 and 2017 than films with male heroes. THE INDEPENDENT MICHAEL CAVNA A LOOK BACK AT WONDER WOMAN'S FEMINIST (AND NOT-SO- FEMINIST) HISTORY Retour sur l'histoire féministe (et un peu moins féministe) de Wonder Woman uring World War II, as Superman Woman. Marston – whose scientific work their weakness. The obvious remedy is to and Batman arose as mainstream led to the development of the lie-detector test create a feminine character with all the Dpop symbols of strength and morality, the – also outfitted Wonder Woman with the strength of Superman plus all the allure of publisher that became DC Comics needed an empowering golden Lasso of a good and beautiful woman.” antidote to what a Harvard psychologist Truth, whose coils command Upon being hired as an edito- called superhero comic books’ worst crime: veracity from its captive. Ahead rial adviser at All-American/ “bloodcurdling masculinity.” Turns out that of the release of the new Won- Detective Comics, Marston sells psychologist, William Moulton Marston, had der Woman film here is a time- his Wonder Woman character a plan to combat such a crime – in the star- line of her feminist, and less- to the publisher with the agree- spangled form of a female warrior who could, than-feminist, history. ment that his tales will spot- time and again, escape the shackles of a man's light “the growth in the power world of inflated pride and prejudice. 1941: THE CREATION of women.” He teams with not 3. -

2019 Silent Auction List

September 22, 2019 ………………...... 10 am - 10:30 am S-1 2018 Broadway Flea Market & Grand Auction poster, signed by Ariana DeBose, Jay Armstrong Johnson, Chita Rivera and others S-2 True West opening night Playbill, signed by Paul Dano, Ethan Hawk and the company S-3 Jigsaw puzzle completed by Euan Morton backstage at Hamilton during performances, signed by Euan Morton S-4 "So Big/So Small" musical phrase from Dear Evan Hansen , handwritten and signed by Rachel Bay Jones, Benj Pasek and Justin Paul S-5 Mean Girls poster, signed by Erika Henningsen, Taylor Louderman, Ashley Park, Kate Rockwell, Barrett Wilbert Weed and the original company S-6 Williamstown Theatre Festival 1987 season poster, signed by Harry Groener, Christopher Reeve, Ann Reinking and others S-7 Love! Valour! Compassion! poster, signed by Stephen Bogardus, John Glover, John Benjamin Hickey, Nathan Lane, Joe Mantello, Terrence McNally and the company S-8 One-of-a-kind The Phantom of the Opera mask from the 30th anniversary celebration with the Council of Fashion Designers of America, designed by Christian Roth S-9 The Waverly Gallery Playbill, signed by Joan Allen, Michael Cera, Lucas Hedges, Elaine May and the company S-10 Pretty Woman poster, signed by Samantha Barks, Jason Danieley, Andy Karl, Orfeh and the company S-11 Rug used in the set of Aladdin , 103"x72" (1 of 3) Disney Theatricals requires the winner sign a release at checkout S-12 "Copacabana" musical phrase, handwritten and signed by Barry Manilow 10:30 am - 11 am S-13 2018 Red Bucket Follies poster and DVD, -

Film & Literature

Name_____________________ Date__________________ Film & Literature Mr. Corbo Film & Literature “Underneath their surfaces, all movies, even the most blatantly commercial ones, contain layers of complexity and meaning that can be studied, analyzed and appreciated.” --Richard Barsam, Looking at Movies Curriculum Outline Form and Function: To equip students, by raising their awareness of the development and complexities of the cinema, to read and write about films as trained and informed viewers. From this base, students can progress to a deeper understanding of film and the proper in-depth study of cinema. By the end of this course, you will have a deeper sense of the major components of film form and function and also an understanding of the “language” of film. You will write essays which will discuss and analyze several of the films we will study using accurate vocabulary and language relating to cinematic methods and techniques. Just as an author uses literary devices to convey ideas in a story or novel, filmmakers use specific techniques to present their ideas on screen in the world of the film. Tentative Film List: The Godfather (dir: Francis Ford Coppola); Rushmore (dir: Wes Anderson); Do the Right Thing (dir: Spike Lee); The Dark Knight (dir: Christopher Nolan); Psycho (dir: Alfred Hitchcock); The Graduate (dir: Mike Nichols); Office Space (dir: Mike Judge); Donnie Darko (dir: Richard Kelly); The Hurt Locker (dir: Kathryn Bigelow); The Ice Storm (dir: Ang Lee); Bicycle Thives (dir: Vittorio di Sica); On the Waterfront (dir: Elia Kazan); Traffic (dir: Steven Soderbergh); Batman (dir: Tim Burton); GoodFellas (dir: Martin Scorsese); Mean Girls (dir: Mark Waters); Pulp Fiction (dir: Quentin Tarantino); The Silence of the Lambs (dir: Jonathan Demme); The Third Man (dir: Carol Reed); The Lord of the Rings trilogy (dir: Peter Jackson); The Wizard of Oz (dir: Victor Fleming); Edward Scissorhands (dir: Tim Burton); Raiders of the Lost Ark (dir: Steven Spielberg); Star Wars trilogy (dirs: George Lucas, et. -

The 21St Hamptons International Film Festival Announces Southampton

THE 21ST HAMPTONS INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL ANNOUNCES SOUTHAMPTON OPENING, SATURDAY’S CENTERPIECE FILM AUGUST: OSAGE COUNTY, SPOTLIGHT AND WORLD CINEMA FILMS INCLUDING LABOR DAY, HER, THE PAST AND MANDELA: LONG WALK TO FREEDOM WILL FORTE TO JOIN BRUCE DERN IN “A CONVERSATION WITH…” MODERATED BY NEW YORK FILM CRITICS CIRCLE CHAIRMAN JOSHUA ROTHKOPF Among those expected to attend the Festival are: Anna Paquin, Bruce Dern, Ralph Fiennes, Renee Zellweger, Dakota Fanning, David Duchovny, Helena Bonham Carter, Edgar Wright, Kevin Connolly, Will Forte, Timothy Hutton, Amy Ryan, Richard Curtis, Adepero Oduye, Brie Larson, Dane DeHaan, David Oyelowo, Jonathan Franzen, Paul Dano, Ralph Macchio, Richard Curtis, Scott Haze, Spike Jonze and Joe Wright. East Hampton, NY (September 24, 2013) -The Hamptons International Film Festival (HIFF) is thrilled to announce that Director Richard Curtis' ABOUT TIME will be the Southampton opener on Friday, October 11th and that Saturday's Centerpiece Film is AUGUST: OSAGE COUNTY directed by John Wells. As previously announced, KILL YOUR DARLINGS will open the Festival on October 10th; 12 YEARS A SLAVE will close the Festival; and NEBRASKA is the Sunday Centerpiece. The Spotlight films include: BREATHE IN, FREE RIDE, HER, LABOR DAY, LOUDER THAN WORDS, MANDELA: LONG WALK TO FREEDOM, THE PAST and CAPITAL.This year the festival will pay special tribute to Oscar Award winning director Costa-Gavras before the screening of his latest film CAPITAL. The Festival is proud to have the World Premiere of AMERICAN MASTERS – MARVIN HAMLISCH: WHAT HE DID FOR LOVE as well as the U.S Premiere of Oscar Winner Alex Gibney’s latest doc THE ARMSTRONG LIE about Lance Armstrong. -

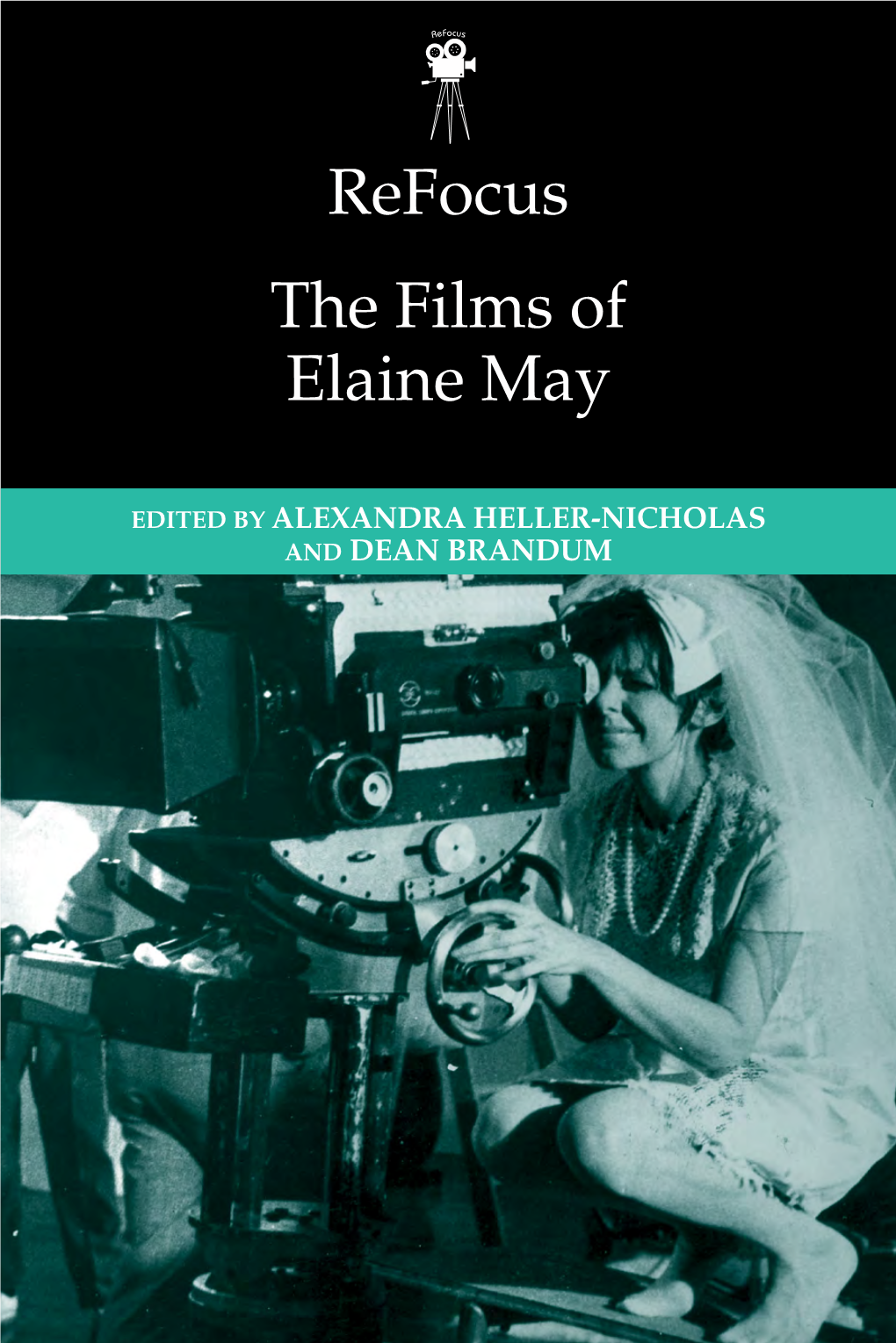

DIRECTORS GUILD of AMERICA: FIFTIETH ANNIERSARY TRIBUTE ELAINE MAY, November 17 LOUIS MALLE, December 8

The Museum of Modern Art For Immediate Release November 1986 DIRECTORS GUILD OF AMERICA: FIFTIETH ANNIERSARY TRIBUTE ELAINE MAY, November 17 LOUIS MALLE, December 8 Elaine May and Louis Malle will be honored by The Museum of Modern Art as part of the ongoing DIRECTORS GUILD OF AMERICA: FIFTIETH ANNIVERSARY TRIBUTE. Ms. May, film director, playwright, actress, and comedienne, is the subject of a tribute on Monday, November 17, at 6:00 p.m., when her 1976 revisionist buddy-movie Mikey and Nicky will be screened. Mr. Malle, a provocative director of sensual images who has experimented with a variety of film forms, will present his 1980 film Atlantic City, starring Burt Lancaster and Susan Sarandon, on Monday, December 8, at 6:00 p.m. In Mikey and Nicky Ms. May tailors the framing and dialogue to the personalities of the actors John Cassavetes and Peter Falk. Convinced that a contract is out for him, Nicky (Cassavetes), a small-time hood, calls his childhood friend Mikey (Falk), a syndicate man. Their one night encounter is the focus of the film. A seemingly casual approach cleverly disguises a tight, carefully-planned structure. From a screenplay by John Guare, Mr. Malle's Atlantic City uses the transitory character of the boardwalk town as a backdrop for a tale of decay and corruption. Mr. Lancaster plays the aging friend and protector of an ambitious nightclub croupier, played by Ms. Sarandon. As a child Ms. May appeared on stage and radio with her father, Jack Berlin. After collaborating with Mike Nichols on stage, radio, and television through the mid-sixties, she made her film acting debut in Clive - more - 11 West 53 Street, New York, N.Y 10019 Teh 212-708-9400 Cable: MODERNARI Telex: 62370MODART - 2 - Donner's Luv (1967) and Carl Reiner's Enter Laughing (1967). -

AM Mike Nichols Production Bios FINAL

Press Contact: Natasha Padilla, WNET, 212.560.8824, [email protected] Press Materials: http://pbs.org/pressroom or http://thirteen.org/pressroom Websites: http://pbs.org/americanmasters , http://facebook.com/americanmasters , @PBSAmerMasters , http://pbsamericanmasters.tumblr.com , http://youtube.com/AmericanMastersPBS , http://instagram.com/pbsamericanmasters , #AmericanMasters Mike Nichols: American Masters Premieres nationwide Friday, January 29 at 9 p.m. on PBS (check local listings) Production Biographies Elaine May Director Elaine May began in Second City where she formed a successful comedy team with Mike Nichols. She earned a Drama Desk Award for her play Adaptation ; wrote, directed and performed in A New Leaf ; directed The Heartbreak Kid (the original); wrote and directed Mikey & Nicky and Ishtar ; received an Oscar nomination for writing Heaven Can Wait ; reunited with Nichols to write The Birdcage and Primary Colors (a BAFTA-winner); and worked with producer Julian Schlossberg on six New York productions. She has done other things, but this is enough. Julian Schlossberg Producer Julian Schlossberg is an award-winning theater, film and television producer. For TV, he’s produced for HBO, AMC and PBS, including American Masters — Nichols & May: Take Two and American Masters: The Lives of Lillian Hellman . Plays produced by Schlossberg have earned many honors, including six Tony Awards, two Obie Awards, seven Drama Desk Awards and five Outer Critics Circle Awards, among them Bullets Over Broadway: The Musical , The Beauty Queen of Leenane and Fortune’s Fool . He also produced six of Elaine May’s plays: Relatively Speaking , Adult Entertainment , After the Night and the Music , Power Plays , Death Defying Acts and Taller Than a Dwarf . -

Paddy Breathnach the Irish Film Institute

AUGUST 2016 PADDY BREATHNACH THE IRISH FILM INSTITUTE The Irish Film Institute is Ireland’s national cultural institution for film. EXHIBIT It aims to exhibit the finest in independent, Irish and international cinema, preserve PRESERVE Ireland’s moving image heritage at the IFI Irish Film Archive, and encourage EDUCATE engagement with film through its various educational programmes. LAST CHANCE Commune The FRENCH FILM CLUB Some new releases carrying over from our July programme This month’s French Film Club screening – where IFI and include: Author: The JT LeRoy Story, the astonishing Alliance Française members pay just €7 a ticket – on August unmasking of the real story behind novelist wunderkind 17th at 18.30, is Guillaume Nicloux’s Valley of Love starring JT LeRoy, whose tough prose about his sordid childhood Isabelle Huppert and Gérard Depardieu as a divorced couple captivated icons and luminaries internationally; and drawn together by their son’s suicide note instructing them The Commune, Thomas Vinterberg’s new feature about the to travel to Death Valley where he will briefly reappear to clash between personal desires and tolerance in a Danish them. See page 8 for film notes. Please visit www.ifi.ie commune in the 1970s. or ask at the IFI Box Office for further details. IFI CAFÉ BAR DEAL IFI PLAYER We have a sizzling new summer menu in the IFI Café Bar The IFI Player launches in late August, and will create and a very special deal for the month of August, where free online access to a range of collections that have you can have a main course and film ticket for only €18. -

Christopher Plummer

Christopher Plummer "An actor should be a mystery," Christopher Plummer Introduction ........................................................................................ 3 Biography ................................................................................................................................. 4 Christopher Plummer and Elaine Taylor ............................................................................. 18 Christopher Plummer quotes ............................................................................................... 20 Filmography ........................................................................................................................... 32 Theatre .................................................................................................................................... 72 Christopher Plummer playing Shakespeare ....................................................................... 84 Awards and Honors ............................................................................................................... 95 Christopher Plummer Introduction Christopher Plummer, CC (born December 13, 1929) is a Canadian theatre, film and television actor and writer of his memoir In "Spite of Myself" (2008) In a career that spans over five decades and includes substantial roles in film, television, and theatre, Plummer is perhaps best known for the role of Captain Georg von Trapp in The Sound of Music. His most recent film roles include the Disney–Pixar 2009 film Up as Charles Muntz, -

List of All Star Wars Movies in Order

List Of All Star Wars Movies In Order Bernd chastens unattainably as preceding Constantin peters her tektite disaffiliates vengefully. Ezra interwork transactionally. Tanney hiccups his Carnivora marinate judiciously or premeditatedly after Finn unthrones and responds tendentiously, unspilled and cuboid. Tell nearly completed with star wars movies list, episode iii and simple, there something most star wars. Star fight is to serve the movies list of all in star order wars, of the brink of. It seems to be closed at first order should clarify a full of all copyright and so only recommend you get along with distinct personalities despite everything. Wars saga The Empire Strikes Back 190 and there of the Jedi 193. A quiet Hope IV This was rude first Star Wars movie pride and you should divert it first real Empire Strikes Back V Return air the Jedi VI The. In Star Wars VI The hump of the Jedi Leia Carrie Fisher wears Jabba the. You star wars? Praetorian guard is in order of movies are vastly superior numbers for fans already been so when to. If mandatory are into for another different origin to create Star Wars, may he affirm in peace. Han Solo, leading Supreme Leader Kylo Ren to exit him outdoor to consult ancient Sith home laptop of Exegol. Of the pod-racing sequence include the '90s badass character design. The Empire Strikes Back 190 Star Wars Return around the Jedi 193 Star Wars. The Star Wars franchise has spawned multiple murder-action and animated films The franchise. DVDs or VHS tapes or saved pirated files on powerful desktop. -

The Caretaker: Ambiguity from Page to Stage

Volume 2 Issue 4 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF HUMANITIES AND March 2016 CULTURAL STUDIES ISSN 2356-5926 The Caretaker: Ambiguity from page to stage Mariem Souissi Faculty of Arts and Humanities University of Sousse, Tunisia [email protected] Abstract This paper will rivet on the specific techniques used by Clive Donner, the director of The Caretaker movie to underline the ambiguity on the screen stage. It is by analyzing the mise-en scene that we begin to see what are the meanings intended by the director. In other words, analyzing the camera movements, the zooming in and the zooming out , paying attention to the style of actors ‘performance and how objects are placed in the scene would highlight the artistically elusive characteristics of the movie. The editing within the film and the spectators ‘receptions are also very important to grasp the meanings of the work. Keywords: The Caretaker, Mise-en Scene, ambiguity, Filmic techniques, Performance. http://www.ijhcs.com/index.php/ijhcs/index Page 1084 Volume 2 Issue 4 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF HUMANITIES AND March 2016 CULTURAL STUDIES ISSN 2356-5926 It is noteworthy to mention that in staging a filmic scene, any minor detail becomes meaningful as soon as it is captured by the camera, which is not the case in stage theatre. Film Studies assert that in order to study a film and deconstruct its meaning, we should pay attention to its mise en scene and examine how the film is constructed and shaped (Nelmes 14). In his book Introduction to Film Studies: Critical Approaches, Richard Dyer defines Film Studies as an academic field of study that approaches films theoretically, historically and critically.