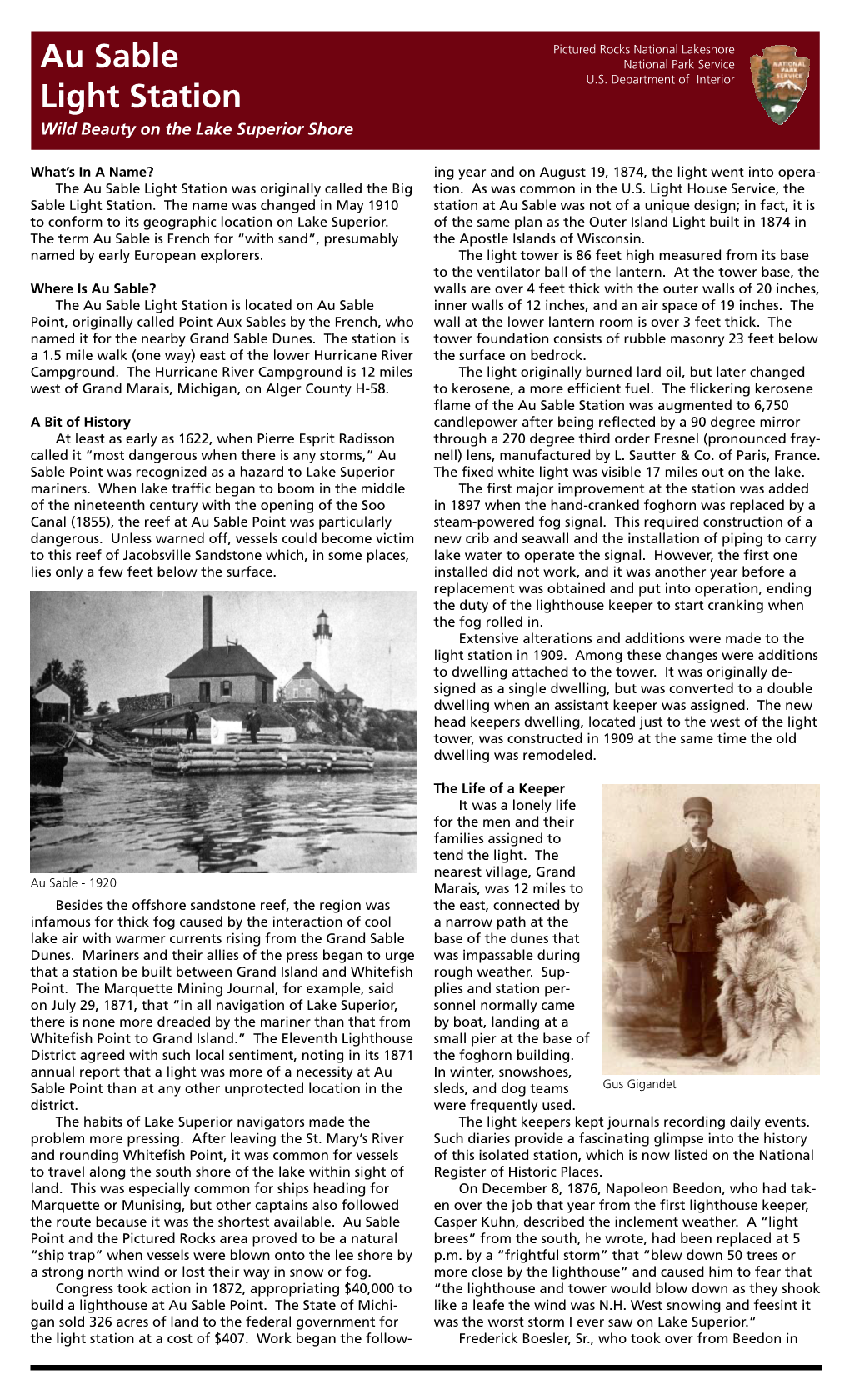

Au Sable Light Station Was Originally Called the Big Tion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Growing up in the Old Point Loma Lighthouse (Teacher Packet)

Growing Up in the Old Point Loma Lighthouse Teacher Packet Program: A second grade program about living in the Old Point Loma Lighthouse during the late 1800s, with emphasis on the lives and activities of children. Capacity: Thirty-five students. One adult per five students. Time: One hour. Park Theme to be Interpreted: The Old Point Loma Lighthouse at Cabrillo National Monument has a unique history related to San Diego History. Objectives: At the completion of this program, students will be able to: 1. List two responsibilities children often perform as a family member today. 2. List two items often found in the homes of yesterday that are not used today. 3. State how the lack of water made the lives of the lighthouse family different from our lives today. 4. Identify two ways lighthouses help ships. History/Social Science Content Standards for California Grades K-12 Grade 2: 2.1 Students differentiate between things that happened long ago and things that happened yesterday. 1. Trace the history of a family through the use of primary and secondary sources, including artifacts, photographs, interviews, and documents. 2. Compare and contrast their daily lives with those of their parents, grandparents, and / or guardians. Meeting Locations and Times: 9:45 a.m. - Meet the ranger at the planter in front of the administration building. 11:00 a.m. - Meet the ranger at the garden area by the lighthouse. Introduction: The Old Point Loma Lighthouse was one of the eight original lighthouses commissioned by Congress for service on the West Coast of the United States. -

Lizard Lighthouse, Lizard Point

U.S. Lighthouse Society ~ Lighthouses of the United Kingdom Lizard Lighthouse (Lizard Point, Cornwall) A NON-PROFIT HISTORICAL & EDUCATIONAL SOCIETY U.S. Lighthouse Society ~ Lighthouses of the United Kingdom History Lizard Lighthouse is a landfall and coastal mark giving a guide to vessels in passage along the English Channel and warning of the hazardous waters off Lizard Point. Many stories are told of the activities of wreckers around our coasts, most of which are grossly exaggerated, but small communities occasionally and sometimes officially benefited from the spoils of shipwrecks, and petitions for lighthouses were, in certain cases, rejected on the strength of local opinion; this was particularly true in the South West of England. The distinctive twin towers of the Lizard Lighthouse mark the most southerly point of mainland Britain. The coastline is particularly hazardous, and from early times the need for a beacon was obvious. Sir John Killigrew, a philanthropic Cornishman, applied for a patent. Apparently, because it was thought that a light on Lizard Point would guide enemy vessels and pirates to a safe landing, the patent was granted with the proviso that the light should be extinguished at the approach of the enemy. Killigrew agreed to erect the lighthouse at his own expense, for a rent of ʺtwenty nobles by the yearʺ, for a term of thirty years. Although he was willing to build the tower, he was too poor to bear the cost of maintenance, and intended to fund the project by collecting from ships that passed the point any voluntary contributions that the owners might offer him. -

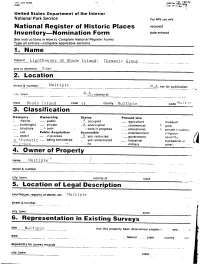

Nayatt Point Lighthouse

- _______ ips ‘orm . - 0MG No Ic 3.12 p It*J.4 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service For NPS use only National Register of Historic Places received Inventory-Nomination Form date entered See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries-complete applicable sections 1. Name - ifistoric Lighthouses_oloesan ILQJiiSIc flrp ana or common Sante - 2. Location - st’eet& number Multiple NA.not for pubncauon c’ty town N vicinity of state Rhode Island code 44 county Multiple code I t I - 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use - district public - occupied agriculture - museum buildings - private ilL unoccupied commercial - park structure - X both - work in progress educational X private r-sdenc, site Public Acquisition Accessible entertainment rn!igious -- object -. -. in process .A yes: restricted government scuentilic x thematic being considered -- yes: unrestricted industrial .. transportator a crott --- no military - other: - 4. Owner of Property - name Multiple street & number city town vicinity of state - - 5. Location of Legal Description - courthouse, registry of deeds. etc. Mu 1 t Ic -- street & number r city, town - state - 6. Representation in Existing Surveys title Multipje has this property been determined eligible? yes date federal -- -- state county "-C - depositorytorsurvey records - -- city, town state - OMO No 1014-0011 I EIP 10-31-54 - NPc Cørm 10900-S - - 3-121 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Inventory_NOminati01 Form - Page Continuation- - sheet 1 Item number 7 TABLE OF CONTENTS Nayatt Point Lighthouse 22 Bristol Ferry Lighthouse -- 27 conanicut Island Lighthouse 31 Jutch Island Lighthouse 34 Ida Lewis Rock Lighthouse 39 ?oplar Point Lighthouse 43 ?ojnt Judith Lighthouse 48 castle Hill Lighthouse 52 Newport Harbor Lighthouse 56 Plum Beach Lighthouse 60 Hog Island Shoal Lighthouse 65 Prudence Island Lighthouse 69 onimicut Lighthouse 73 Warwick Lighthouse 78 I date 7. -

U.S. Coast Guard Historian's Office

U.S. Coast Guard Historian’s Office Preserving Our History For Future Generations Historic Light Station Information MARYLAND BALTIMORE LIGHT Location: South entrance to Baltimore Channel, Chesapeake Bay, off the mouth of the Magothy River Date Built: Commissioned 1908 Type of Structure: Caisson with octagonal brick dwelling / light tower Height: 52 feet above mean high water Characteristics: Flashing white with one red sector Foghorn: Yes (initially bell, replaced with a horn by 1923) Builder: William H. Flaherty / U. S. Fidelity and Guarantee Co. Appropriation: $120,000 + Range: white – 7 miles, red – 5 miles Status: Standing and Active Historical Information: This is one of the last lighthouses built on the Chesapeake Bay. The fact that it was built at all is a testimony to the importance of Baltimore as a commercial port. The original appropriation request to Congress for a light at this location was made in 1890 and $60,000 was approved four years later. However, bottom tests of proposed sites showed a 55 foot layer of semi-fluid mud before a sand bottom was hit. This extreme engineering challenge made construction of a light within the proposed cost impossible. An additional $60,000 was requested and finally appropriated in 1902. Even then, the project had to be re-bid because no contractor came forth within the allotted budget. Finally, the contract was awarded to William H. Flaherty (who had built the Solomon’s Lump and Smith Point lights). The materials were gathered and partially assembled at Lazaretto Point Depot, then towed to the site and lowered to the bottom in September 1902. -

The Historic Point Reyes Lighthouse PRNS Archives a Challenging Place

Point Reyes Department of the Interior National Seashore National Park Service The Historic Point Reyes Lighthouse PRNS Archives A Challenging Place “Better to dwell in the midst of alarms than reign in this horrible place.” ~ attributed to a lighthouse keeper at Point Reyes Virtually overnight, the California Gold Rush transformed the city of San Francisco from a sleepy bayside hamlet of about 1000 citizens to an international destination. The port hummed with activity. Would- be prospectors and ambitious merchants docked alongside cargo ships laden with mining and building materials, farm produce, and other supplies. People from all over the world boarded ships with the dream of striking it rich in the hills of California, and the main point of debarkation was San Francisco. But navigating Golden Gate NRA, Park Archives the ferocious currents, foggy conditions, jagged cliffs, Looking down at the busy wharves along San Francisco Bay from and off-shore rocks of the California coastline was a th the city’s famous hills in the mid-19 Century. daunting proposition. In the newly-established state of California, navigational aids were virtually nonexistent. In 1853 the first California lighthouse was constructed on Alcatraz Island—then an army fort—and lit in 1854. After the gold rush, Point Reyes became San Francisco’s chief supplier of dairy products and hogs, carried by schooners which sailed from Tomales Bay and Drakes Estero to the city. As early as 1849, it was recognized that Point Reyes would play an important role in the protection of coastal traffic and in the economic prosperity of the western United States. -

The Cleveland Naturalists' Report on the Flora of the Coast

A CLEVELAND NATURALISTS' FIELD CLUB BULLETIN 1994 THE CLEVELAND COAST FLORA AND HISTORY 1INTRODUCTION................................................................................................ 1 1.1DETAILS OF THE SURVEY........................................................................ 2 2THE RIVER TEES AND THE SOUTH GARE.................................................... 3 3THE FLORA OF THE COAST............................................................................ 8 3.1SOUTH GARE ............................................................................................ 8 3.2COATHAM DUNES................................................................................... 13 3.3COATHAM AND REDCAR ....................................................................... 14 3.4REDCAR STRAY....................................................................................... 16 3.4.1THE FLORA OF THE STRAY ............................................................ 17 3.5MARSKE.................................................................................................... 18 3.5.1THE FLORA OF THE COAST BETWEEN MARSKE AND SALTBURN. 19 3.6CAT NAB................................................................................................... 21 3.6.1THE FLORA OF CAT NAB................................................................. 21 3.7SALTBURN................................................................................................ 22 3.8SALTBURN TO SKINNINGROVE............................................................ -

The Lizard & the Cloch – Time and Place in 19Th

Invisible Places 7– 9 APRIL 2017 SÃO MIGUEL ISLAND, AZORES, PORTUGAL 278 The Lizard & The Cloch – Time and Place in 19th Century Foghorn Installations JENNIFER LUCY ALLAN [email protected] CRiSAP, London, UK ABSTRACT: This paper will present two previously unknown cases of noise complaints in the UK in the late 19th Century, detailing reactions to new foghorns at The Lizard in Cornwall in the 1870s, and at the Cloch lighthouse at the mouth of the Clyde in 1897. I will address what these two case studies can tell us about the way the sound of the foghorn was received into the coastal environment, how feelings about this sound in the coastal sound- scape change over time, and how foghorns affected a sense of place for the individuals living there. KEYWORDS: foghorns, place, time, sound phobia, sound romance, 19th century. 279 1. Introduction This paper will detail two noise complaints from The Lizard in Cornwall and the Cloch on the Firth of Clyde, regarding the installation of new foghorns at the end of the 19th Century. The former is sourced from the archives of the Board of Trade, an held in the brutalist bul- wark of the National Archives in Kew outside London. The second is sourced from the Clyde Lighthouses Trust, a small lighthouse body that was responsible for a small area of the Firth of Clyde from Greenock to Little Cumbrae, and whose archive is only partially indexed at the Mitchell Library in Glasgow. In existing literature the voices documented from this period are often restricted to in- ternal communications of the lighthouse authorities, but in locations where foghorns were installed they brought about a dramatic shift in the coastal soundscape. -

FOGHORN REQUIEM FOGHORN REQUIEM Foghorn Requiem Is a Performance, Marking the Disappearance of the Sound of the Foghorn from the UK’S Coastal Landscape

FOGHORN REQUIEM FOGHORN REQUIEM Foghorn Requiem is a performance, marking the disappearance of the sound of the foghorn from the UK’s coastal landscape. Seventy-five brass players and more than fifty vessels will gather at Souter lighthouse to perform together with the lighthouse foghorn itself. The sound of a distant foghorn has always connected the land and the sea; a melancholy, friendly call that we remember from childhood - a sound that has always felt like a memory. The sound of the foghorn is uniquely shaped by the landscape through which it travels. Very few sounds are so loud, and heard at such great distances. As a result the actual sound of the horn is almost always heard softened, smeared out and thickened by the innumerable echoes and reverberations of the landscape in which it exists. The characteristically haunting tone of a distant foghorn is the imprint of the land encoded into the sound itself, an embodiment of the landscape and history of a place. We have tried to create an event that incorporates this sense of the landscape and history into a musical performance. New technology will allow ships horns several miles off shore to play together with musicians on shore, a gathering of three of the finest historical brass bands of the North East. In the performance sounds will be affected by distance, weather, and landscape, and so we have avoided using any kind of amplification. There will be extraordinarily loud moments, but there will also be very quiet periods. The performance of Foghorn Requiem is therefore a delicate sound experience that will depend on the silence and quality of attention of the audience. -

Souter Point Lighthouse, Marsden in South Tyneside

U.S. Lighthouse Society ~ Lighthouses of the United Kingdom Souter Point Lighthouse (Marsden in South Tyneside, Tyne and Wear) History The lighthouse is located on Lizard Point at Marsden, but takes its name from Souter Point, which is located a mile to the south. This was the intended site for the lighthouse, but it was felt that Lizard Point offered better visibility, as the cliffs there are higher, so the lighthouse was built there instead. The Souter Lighthouse name was retained in order to avoid confusion with the then recently built Lizard Lighthouse in Cornwall. Designed by James Douglass and opened in 1871, the lighthouse was built due to the dangerous reefs directly under the water in the surrounding area. In one year alone - 1860 - there were 20 shipwrecks. This contributed to making this coastline the most dangerous in the country with an average of around 44 shipwrecks per every mile of coastline. A NON-PROFIT HISTORICAL & EDUCATIONAL SOCIETY U.S. Lighthouse Society ~ Lighthouses of the United Kingdom Souter Lighthouse was the first to use alternating electric current, the most advanced lighthouse technology of its day. Douglass also designed the fourth incarnation of the Eddystone Lighthouse off the coast of Plymouth. The 800,000 candle power light was generated using carbon arcs and not a standard filament bulb and could be seen for up to 26 miles. The electricity was generated using a steam engine located in the engine house. Today owned by the National Trust and open to the public, the lighthouse's engine room, light tower and keeper's living quarters are all on view. -

The Loss of the South Goodwin Lightship LV-90

Home About Me Contact Blog MARITIME ARCHAEOLOGY, MARITIME HISTORY The Loss of The South Goodwin Lightship LV-90 “…The South Goodwin Lightship Search could just be seen, a dim red barque Search … !! married forever to the same compass point and condemned, like a property ship on the stage of Drury Lane, to watch a diorama of waves and clouds sail busily into the wings. Without papers or passengers or cargo, it lay anchored forever to the departure point which was also its destination….anchored to the gates of a graveyard.” Ian Fleming, Moonraker The Danger of Lightship Duty Although life aboard a lightship was routine and monotonous, it was beset with moments that were a true test of courage. The unfortunate story that this blog post is going to relate is a perfect testament to the danger of lightship duty. I wanted to continue the theme of the previous blog posts regarding my research into LV-95 by relating a story of survival that illustrates both the inherent hazard and therefore the importance of lightship duty. Lightships have long since been eclipsed by modern technology with the last American lightship Nantucket being taken off station in 1985 and the LV- 95 being taken off station from the port of Milwaukee by the installation of a radio beacon. It is the feeling of this author that people have forgotten what these ships are and what they did. I have recently obtained the rare model kit of the South Goodwin produced by Revell not knowing the tragic history behind this ship and that is my inspiration for this blog post. -

Environmental Appraisal (EA) for the Argyll Tidal Demonstrator Project

Argyll Tidal Demonstrator Project Argyll Tidal Limited Environmental Appraisal (EA) for the Argyll Tidal Demonstrator Project (December 2013) A single unit demonstration of Nautricity’s CoRMaT tidal stream turbine technology to be deployed in the coastal waters of the Mull of Kintyre, Scotland. CoRMaT at the Port of Montrose Environmental Appraisal Argyll Tidal Demonstrator Project Argyll Tidal Limited 1 INTRODUCTION 1.1 BACKGROUND 1. In October 2011, Argyll Tidal Limited (ATL) (“the Applicant”) entered into an Agreement for Lease with The Crown Estate under Section 3 of the Crown Estate Act 1961. This agreement initiated the investigation of the potential for development of a demonstration tidal energy array of up to 3 MW scale (“the Development”) to be located in the North Channel off the western coast of the Mull of Kintyre, Argyll and Bute, Scotland (“the Development Site”). The Development Site location is shown on Figure 1.1. Figure 1.1 – Development Site location 2. ATL is working with Nautricity Limited (NL), a Scottish developer of tidal generation technology. NL has developed the 500 kW CoRMaT device. It was originally proposed that up to 6 of these devices would be deployed at the Development Site subject to the appropriate consents and licences being granted. Consent to construct and operate the Development would fall under Section 36 of the Electricity Act 1989 and a Marine Licence would also be required under the Marine Scotland Act 2010. 3. Schedule 2 of the Electricity Works (Environmental Impact Assessment) (Scotland) Regulations (2000) requires that all projects falling under S36 of the Electricity Act be screened to determine whether an Environmental Statement will be required to accompany the consent application. -

P a S S a G E S

DeTour Reef Light Preservation Society P A S S A G E S * PO Box 307 * Drummond Island MI 49726 * [email protected] * www.DRLPS.com * 906-493-6609 * 1931 Today! Issue 26 We’ll Keep the Light on for You! Fall 2012 Shedding Some Light on the Lenses of the DeTour Reef Light by David Bardsley The history of the illumination and lenses of DeTour Reef Light begins with a meticulously craft- ed 1908 French Fresnel lens to the current beacon that looks like something from “Star Wars.” A somewhat technical and boring (according to my wife Paula) summary follows. When DeTour Reef Light Station was constructed in 1930-31, the 1861 light- house tower from DeTour Point with its 1908 3½-order Fresnel lens was relo- cated to the reef light station. This lens was configured as a flashing white light with a characteristic of a one-second flash and a nine-second eclipse. The lens was manufactured by Barbier, Benard & Turenne Co. of Paris, France at a cost of $2,940.50 ($73,512 in 2012 dollars). The original shipping weight of the lens and components was 4,480 lbs. In 1936, the color changed from 3 ½ order Fresnel Lens from straight white to white with a red sector to the North West to warn of DeTour Reef Light now on the dangerous reef. This was accomplished using a color plastic inside display in DeTour Passage the lantern (the glass-enclosed room containing the beacon) which is Historical Museum unchanged to this date. In 1978, the Fresnel lens was removed and replaced by a modern bea- con.