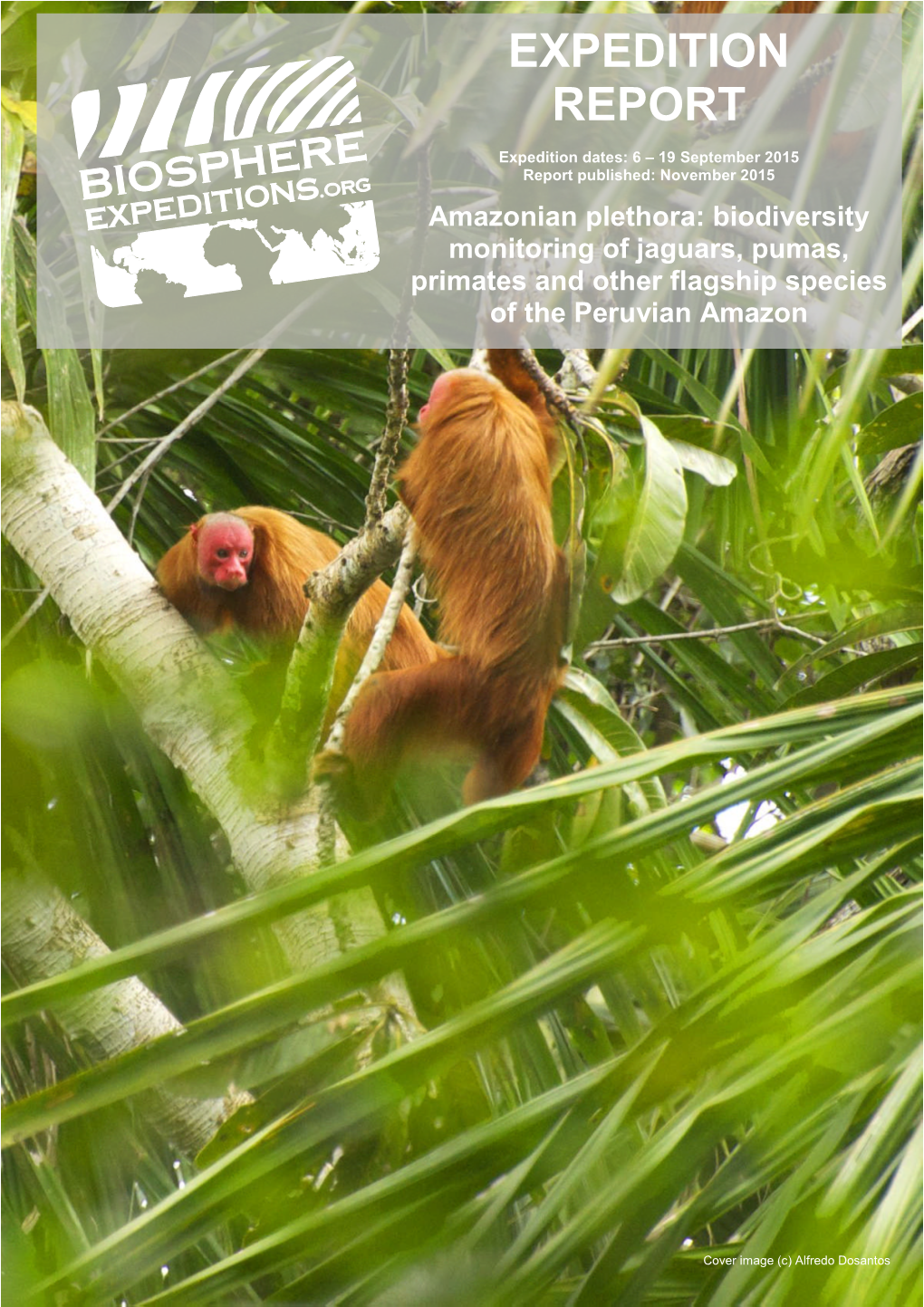

Expedition Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sciurus Ignitus (Rodentia: Sciuridae)

46(915):93–100 Sciurus ignitus (Rodentia: Sciuridae) MELISSA J. MERRICK,SHARI L. KETCHAM, AND JOHN L. KOPROWSKI Wildlife Conservation and Management, School of Natural Resources and the Environment, 1311 E. 4th Street, Biological Sciences East Room 325, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ 85721, USA; [email protected] (MJM); sketcham@email. arizona.edu (SLK); [email protected] (JLK) Abstract: Sciurus ignitus (Gray, 1867) is a Neotropical tree squirrel commonly known as the Bolivian squirrel. It is a small- bodied, understory and mid-canopy dweller that occurs within the evergreen lowland and montane tropical rain forests along Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/mspecies/article/46/915/93/2643022 by guest on 15 June 2021 the eastern slope of the Andes in Peru, Bolivia, and extreme northern Argentina, and the western Amazon Basin in Brazil and Peru between 200 and 2,700 m in elevation. S. ignitus is 1 of 28 species in the genus Sciurus, and 1 of 8 in the subgenus Guerlinguetus. The taxonomic status of this species, as with other small sciurids in Peru and Bolivia, remains ambiguous. S. ignitus is currently listed as ‘‘Data Deficient’’ by the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources. Key words: Andes, Bolivia, Neotropics, Peru, tree squirrel Ó 18 December 2014 American Society of Mammalogists Synonymy completed 1 June 2014 DOI: 10.1644/915.1 www.mammalogy.org Sciurus ignitus (Gray, 1867) Sciurus (Mesociurus) argentinius Thomas, 1921:609. Type Bolivian Squirrel locality ‘‘Higuerilla, 2000 m, in the Department of Valle Grande, about 10 km. east of the Zenta range and 20 Macroxus ignitus Gray, 1867:429. -

The Survival of the Central American Squirrel Monkey

SIT Graduate Institute/SIT Study Abroad SIT Digital Collections Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection SIT Study Abroad Fall 2005 The urS vival of the Central American Squirrel monkey (Saimiri oerstedi): the habitat and behavior of a troop on the Burica Peninsula in a conservation context Liana Burghardt SIT Study Abroad Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection Part of the Animal Sciences Commons, and the Environmental Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Burghardt, Liana, "The urS vival of the Central American Squirrel monkey (Saimiri oerstedi): the habitat and behavior of a troop on the Burica Peninsula in a conservation context" (2005). Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection. 435. https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection/435 This Unpublished Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the SIT Study Abroad at SIT Digital Collections. It has been accepted for inclusion in Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection by an authorized administrator of SIT Digital Collections. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Survival of the Central American Squirrel monkey (Saimiri oerstedi): the habitat and behavior of a troop on the Burica Peninsula in a conservation context Liana Burghardt Carleton College Fall 2005 Burghardt 2 I dedicate this paper which documents my first scientific adventure in the field to my father. “It is often necessary to put aside the objective measurements favored in controlled laboratory environments and to adopt a more subjective naturalistic viewpoint in order to see pattern and consistency in the rich, varied context of the natural environment” (Baldwin and Baldwin 1971: 48). Acknowledgments This paper has truly been an adventure and as is common I have many people I wish to thank. -

Common Squirrel Monkey Scientific Name: Saimiri Sciureus

Common Squirrel Monkey Scientific Name: Saimiri sciureus Class: Mammalia Order: Primates Family: Cebidae The head and body length is 10.4 to 14.4 in.; tail length is 14 to 17 in; and weight is 2.5 to 3.7 lb. The tail is not prehensile. These diurnal monkeys are arboreal and only occasionally descend to the ground. Movement is quadrupedal with relatively little leaping. Ranges are often ill-defined and troops may number into the 40-50 range. During the mating season males establish a dominance hierarchy through fierce fighting with the higher-ranking individuals then interacting with the females. The females establish a dominance hierarchy during pregnancy. After the birth of the young, females exclude the males. The newborn cling to their mothers back for the first few weeks of life. Independence is achieved at 1 year. Range East of the Andes from Colombia and northern Peru to north- eastern Brazil Habitat Primary and secondary forests, cultivated areas, usually along streams Gestation 152-172 days Litter 1 Behavior These diurnal monkeys are arboreal and only occasionally descend to the ground. Movement is quadrupedal with relatively little leaping. Wild troops are most active from early to mid-morning and mid- to late afternoon, usually resting an hour or two at midday. Ranges are often ill-defined, and troops may number into the 40-50 range. Groups are known to split during the day into subgroups of pregnant females, females with young and adult males. Reproduction During the mating season males establish a dominance hierarchy through fierce fighting with the higher-ranking individuals then interacting with the females. -

Saimiri Sciureus) by an Amazon Tree Boa (Corallus Hortulanus

Predation of a squirrel monkey (Saimiri sciureus) by an Amazon tree boa (Corallus hortulanus): even small boids may be a potential threat to small-bodied platyrrhines Marco Antônio Ribeiro-Júnior, Stephen Francis Ferrari, Janaina Reis Ferreira Lima, Claudia Regina da Silva & Jucivaldo Dias Lima Primates ISSN 0032-8332 Primates DOI 10.1007/s10329-016-0545-z 1 23 Your article is protected by copyright and all rights are held exclusively by Japan Monkey Centre and Springer Japan. This e-offprint is for personal use only and shall not be self- archived in electronic repositories. If you wish to self-archive your article, please use the accepted manuscript version for posting on your own website. You may further deposit the accepted manuscript version in any repository, provided it is only made publicly available 12 months after official publication or later and provided acknowledgement is given to the original source of publication and a link is inserted to the published article on Springer's website. The link must be accompanied by the following text: "The final publication is available at link.springer.com”. 1 23 Author's personal copy Primates DOI 10.1007/s10329-016-0545-z NEWS AND PERSPECTIVES Predation of a squirrel monkey (Saimiri sciureus) by an Amazon tree boa (Corallus hortulanus): even small boids may be a potential threat to small-bodied platyrrhines 1 2,3 4,5 Marco Antoˆnio Ribeiro-Ju´nior • Stephen Francis Ferrari • Janaina Reis Ferreira Lima • 5 4,5 Claudia Regina da Silva • Jucivaldo Dias Lima Received: 19 April 2016 / Accepted: 29 April 2016 Ó Japan Monkey Centre and Springer Japan 2016 Abstract Predation has been suggested to play a major capable of capturing an agile monkey like Saimiri, C. -

Squirrel Monkeys and Space Motion Sickness

Japanese Journal of Physiology, 52, 1–20, 2002 REVIEW Squirrel Monkeys and Space Motion Sickness Kenichi MATSUNAMI Science and Technology Promotion Center, Kakamigahara, 509–0108 Japan Abstract: Studies of the vestibular system in system is crucially important in the genesis of squirrel monkeys in consideration of space mo- SMS (SAS). In this connection, the ablation stud- tion sickness (SMS) or space adaptation syn- ies of labyrinth, semicircular canals, and other drome (SAS) were reviewed. First, the phyloge- SAS-related areas were referred to, and consid- netic position of the squirrel monkey was consid- eration was made for experiments about caloric ered. Then the anatomico-physiological studies irrigation of the ear. A hypothetic model was then of both the peripheral and the central vestibular proposed for the genesis of SAS. [Japanese systems were described, because the vestibular Journal of Physiology, 52, 1–20, 2002] Key words: squirrel monkey, vestibular system, cerebral cortex, space motion sickness (SMS), space adaptation syndromes (SAS). The construction of the new space station will be contamination of fatal B virus for human subjects; (4) completed soon, and many experiments will be under- They are relatively free from dysentery or tuberculo- taken. Many Japanese scientists will join in these new sis; (5) They are less dangerous because of their small experiments. Animal experiments are expected to size. On the other hand, (1) They are small and weak, solve problems in space physiology. Several kinds of thus vulnerable to bleeding during surgery; (2) The nonhuman primates such as the chimpanzee (Pan bone of the skull is thin, and it is difficult to perma- troglodytes), common squirrel monkey (Saimiri sci- nently anchor a cylinder to the skull for a continuous urea), rhesus monkey (Macaca mulatta), and stump- recording of neuronal activity; (3) They are expensive, tailed monkey (Macaca speciosa) have already been particularly in Japan, because of their high mortality used. -

Matses Indian Rainforest Habitat Classification and Mammalian Diversity in Amazonian Peru

Journal of Ethnobiology 20(1): 1-36 Summer 2000 MATSES INDIAN RAINFOREST HABITAT CLASSIFICATION AND MAMMALIAN DIVERSITY IN AMAZONIAN PERU DAVID W. FLECK! Department ofEveilltioll, Ecology, alld Organismal Biology Tile Ohio State University Columbus, Ohio 43210-1293 JOHN D. HARDER Oepartmeut ofEvolution, Ecology, and Organismnl Biology Tile Ohio State University Columbus, Ohio 43210-1293 ABSTRACT.- The Matses Indians of northeastern Peru recognize 47 named rainforest habitat types within the G61vez River drainage basin. By combining named vegetative and geomorphological habitat designations, the Matses can distinguish 178 rainforest habitat types. The biological basis of their habitat classification system was evaluated by documenting vegetative ch<lracteristics and mammalian species composition by plot sampling, trapping, and hunting in habitats near the Matses village of Nuevo San Juan. Highly significant (p<:O.OOI) differences in measured vegetation structure parameters were found among 16 sampled Matses-recognized habitat types. Homogeneity of the distribution of palm species (n=20) over the 16 sampled habitat types was rejected. Captures of small mammals in 10 Matses-rc<:ognized habitats revealed a non-random distribution in species of marsupials (n=6) and small rodents (n=13). Mammal sighlings and signs recorded while hunting with the Matses suggest that some species of mammals have a sufficiently strong preference for certain habitat types so as to make hunting more efficient by concentrating search effort for these species in specific habitat types. Differences in vegetation structure, palm species composition, and occurrence of small mammals demonstrate the ecological relevance of Matses-rccognized habitat types. Key words: Amazonia, habitat classification, mammals, Matses, rainforest. RESUMEN.- Los nalivos Matslis del nordeste del Peru reconacen 47 tipos de habitats de bosque lluvioso dentro de la cuenca del rio Galvez. -

Northern Ecuador, 2010

Northern Ecuador, February 13th ʹ March 5h 2010 This was mainly a birding trip made by myself, Steven De Saeger and Filiep T͛Jollyn, but we all have an interest in all kinds of animals. This was also one of my last trips without a decent camera, so the few pictures in this report were all taken with a compact camera. The highlight of the trip in fact was one of the triggers for me to buy a decent camera͙ Most of the report will be some short notes about which species were seen where (I wrote this more than four years later, so I don͛t recall all details about trails etc. ʹ a good lesson to myself: don͛t wait too long to write a report!). Saturday February 13th 2010 Filiep and I flew in via Atlanta, and Steven from Madrid. Upon arriving in Atlanta, we experienced a huge snow storm, with many flights being delayed or even cancelled. Fortunately, after waiting for some hours, our flight left with a delay of about 5 hours. We met Steven and our guide for the first day at the airport well after midnight, and quickly set off towards Pululahua Crater. This night drive resulted in the first mammal of the trip, a Tapiti. The rest of the day I got a first impression of birding in South America, but no more mammals were seen. Sunday February 14th 2010 An early drive to the airport, for a short flight over the Andes, brought us to Coca, from where we would be taken to the Amazon. -

Table 7: Species Changing IUCN Red List Status (2018-2019)

IUCN Red List version 2019-3: Table 7 Last Updated: 10 December 2019 Table 7: Species changing IUCN Red List Status (2018-2019) Published listings of a species' status may change for a variety of reasons (genuine improvement or deterioration in status; new information being available that was not known at the time of the previous assessment; taxonomic changes; corrections to mistakes made in previous assessments, etc. To help Red List users interpret the changes between the Red List updates, a summary of species that have changed category between 2018 (IUCN Red List version 2018-2) and 2019 (IUCN Red List version 2019-3) and the reasons for these changes is provided in the table below. IUCN Red List Categories: EX - Extinct, EW - Extinct in the Wild, CR - Critically Endangered [CR(PE) - Critically Endangered (Possibly Extinct), CR(PEW) - Critically Endangered (Possibly Extinct in the Wild)], EN - Endangered, VU - Vulnerable, LR/cd - Lower Risk/conservation dependent, NT - Near Threatened (includes LR/nt - Lower Risk/near threatened), DD - Data Deficient, LC - Least Concern (includes LR/lc - Lower Risk, least concern). Reasons for change: G - Genuine status change (genuine improvement or deterioration in the species' status); N - Non-genuine status change (i.e., status changes due to new information, improved knowledge of the criteria, incorrect data used previously, taxonomic revision, etc.); E - Previous listing was an Error. IUCN Red List IUCN Red Reason for Red List Scientific name Common name (2018) List (2019) change version Category -

MAMÍFEROS Diversidad Endémica Requiere De Muchos Años De Autor: Mario Escobedo Torres Estudio

.................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... .............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................no. 27 ....................................................................................................................... 27 Perú: Tapiche-Blanco Perú:Tapiche-Blanco Instituciones participantes/ Participating Institutions The Field Museum Centro para el Desarrollo del Indígena Amazónico (CEDIA) Instituto de Investigaciones de la Amazonía Peruana (IIAP) Servicio Nacional de Áreas Naturales Protegidas por el Estado (SERNANP) Servicio Nacional Forestal y de Fauna Silvestre (SERFOR) Herbario Amazonense de la Universidad Nacional de la Amazonía Peruana (AMAZ) Museo de Historia Natural de la Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos Centro de Ornitología y Biodiversidad (CORBIDI) -

A Re-Evaluation of Allometric Relationships for Circulating Concentrations of Glucose in Mammals

Food and Nutrition Sciences, 2016, 7, 240-251 Published Online April 2016 in SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/fns http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/fns.2016.74026 A Re-Evaluation of Allometric Relationships for Circulating Concentrations of Glucose in Mammals Colin G. Scanes Department of Biological Science, University of Wisconsin Milwaukee, Milwaukee, WI, USA Received 10 August 2015; accepted 19 April 2016; published 22 April 2016 Copyright © 2016 by author and Scientific Research Publishing Inc. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY). http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Abstract Purpose: The present study examined the putative relationship between circulating concentra- tions of glucose and log10 body weight in a large sample size (270) of wild species but with domes- ticated animals excluded from the analyses. Methods: A data-set of plasma/serum concentration of glucose and body weight in mammalian species was developed from the literature. Allometric re- lationships were examined. Results: In contrast to previous reports, no overall relationship for circulating concentrations of glucose was observed across 270 species of mammals (for log10 glu- cose concentration adjusted R2 = −0.003; for glucose concentration adjusted R2 = −0.003). In con- trast, a strong allometric relationship was observed for circulating concentrations of glucose in 2 Primates (for log10 glucose concentration adjusted R = 0.511; for glucose concentration adjusted R2 = 0.480). Conclusion: The absence of an allometric relationship for circulating concentrations of glucose was unexpected. A strong allometric relationship was seen in Primates. Keywords Glucose, Allometric, Mammals, Primates 1. Introduction Glucose in the blood is the principal energy source for brain functioning and but glucose can be used as the energy source for multiple other tissues. -

The Historical Ecology of Human and Wild Primate Malarias in the New World

Diversity 2010, 2, 256-280; doi:10.3390/d2020256 OPEN ACCESS diversity ISSN 1424-2818 www.mdpi.com/journal/diversity Article The Historical Ecology of Human and Wild Primate Malarias in the New World Loretta A. Cormier Department of History and Anthropology, University of Alabama at Birmingham, 1401 University Boulevard, Birmingham, AL 35294-115, USA; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-205-975-6526; Fax: +1-205-975-8360 Received: 15 December 2009 / Accepted: 22 February 2010 / Published: 24 February 2010 Abstract: The origin and subsequent proliferation of malarias capable of infecting humans in South America remain unclear, particularly with respect to the role of Neotropical monkeys in the infectious chain. The evidence to date will be reviewed for Pre-Columbian human malaria, introduction with colonization, zoonotic transfer from cebid monkeys, and anthroponotic transfer to monkeys. Cultural behaviors (primate hunting and pet-keeping) and ecological changes favorable to proliferation of mosquito vectors are also addressed. Keywords: Amazonia; malaria; Neotropical monkeys; historical ecology; ethnoprimatology 1. Introduction The importance of human cultural behaviors in the disease ecology of malaria has been clear at least since Livingstone‘s 1958 [1] groundbreaking study describing the interrelationships among iron tools, swidden horticulture, vector proliferation, and sickle cell trait in tropical Africa. In brief, he argued that the development of iron tools led to the widespread adoption of swidden (―slash and burn‖) agriculture. These cleared agricultural fields carved out a new breeding area for mosquito vectors in stagnant pools of water exposed to direct sunlight. The proliferation of mosquito vectors and the subsequent heavier malarial burden in human populations led to the genetic adaptation of increased frequency of sickle cell trait, which confers some resistance to malaria. -

Molecular Evolution and Phylogenetic Importance of a Gamete Recognition Gene Zan Reveals a Unique Contribution to Mammalian Speciation

Molecular evolution and phylogenetic importance of a gamete recognition gene Zan reveals a unique contribution to mammalian speciation. by Emma K. Roberts A Dissertation In Biological Sciences Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Tech University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Approved Robert D. Bradley Chair of Committee Daniel M. Hardy Llewellyn D. Densmore Caleb D. Phillips David A. Ray Mark Sheridan Dean of the Graduate School May, 2020 Copyright 2020, Emma K. Roberts Texas Tech University, Emma K. Roberts, May 2020 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank numerous people for support, both personally and professionally, throughout the course of my degree. First, I thank Dr. Robert D. Bradley for his mentorship, knowledge, and guidance throughout my tenure in in PhD program. His ‘open door policy’ helped me flourish and grow as a scientist. In addition, I thank Dr. Daniel M. Hardy for providing continued support, knowledge, and exciting collaborative efforts. I would also like to thank the remaining members of my advisory committee, Drs. Llewellyn D. Densmore III, Caleb D. Phillips, and David A. Ray for their patience, guidance, and support. The above advisors each helped mold me into a biologist and I am incredibly gracious for this gift. Additionally, I would like to thank numerous mentors, friends and colleagues for their advice, discussions, experience, and friendship. For these reasons, among others, I thank Dr. Faisal Ali Anwarali Khan, Dr. Sergio Balaguera-Reina, Dr. Ashish Bashyal, Joanna Bateman, Karishma Bisht, Kayla Bounds, Sarah Candler, Dr. Juan P. Carrera-Estupiñán, Dr. Megan Keith, Christopher Dunn, Moamen Elmassry, Dr.