Why Real Change Is So Difficult in Law Schools

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Endless Summer Cinema Free Outdoor Movies Across the Street from the Site of the New BAM/PFA

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Media Contact: Karen Larsen [email protected] (415) 957-1205 University of California, Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive and the Downtown Berkeley Association present Endless Summer Cinema Free outdoor movies across the street from the site of the new BAM/PFA TWO FREE OUTDOOR FILM SCREENINGS CELEBRATE BAM/PFA’S MOVE TO DOWNTOWN BERKELEY; SCREENINGS OF PEE-WEE’S BIG ADVENTURE (OCT. 3) AND THIS IS SPINAL TAP (OCT. 10) WILL TAKE PLACE ON THE UC BERKELEY CRESCENT LAWN ACROSS THE STREET FROM THE NEW BAM/PFA BUILDING SITE Berkeley, CA, August 22, 2014—The University of California, Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive (BAM/PFA) will host a pair of free outdoor movies across the street from the site of BAM/PFA’s future home in downtown Berkeley on consecutive Fridays in early October 2014. A copresentation with the Downtown Berkeley Association, Endless Summer Cinema will feature two hilarious eighties comedies that became a template for new styles of comedic filmmaking—the strange Technicolor playground of Tim Burton’s first film, Pee-wee’s Big Adventure, and the rockumentary that begat all rockumentaries, Rob Reiner’s This is Spinal Tap. Pee-wee’s Big Adventure (1985) takes audiences on a lovably absurd cross-country journey on October 3 as Paul Ruebens’s Pee-wee Herman character hits the road to recover his most prized possession: a tricked- out forties Schwinn cruiser. Encounters with a fraudulent psychic, a jealous lover, and a biker gang guarantee a memorable trip. The highly stylized film launched the directorial career of Tim Burton, who would continue with a hugely successful run of his quirky and visually distinctive comedies throughout the eighties and nineties. -

Adapting Copyright for the Mashup Generation

ARTICLE ADAPTING COPYRIGHT FOR THE MASHUP GENERATION PETER S. MENELL† Growing out of the rap and hip hop genres as well as advances in digital editing tools, music mashups have emerged as a defining genre for post-Napster generations. Yet the uncertain contours of copyright liability as well as prohibitive transaction costs have pushed this genre underground, stunting its development, limiting remix artists’ commercial channels, depriving sampled artists of fair compensation, and further alienating netizens and new artists from the copyright system. In the real world of transaction costs, subjective legal standards, and market power, no solution to the mashup problem will achieve perfection across all dimensions. The appropriate inquiry is whether an allocation mechanism achieves the best overall resolution of the trade-offs among authors’ rights, cumulative creativity, freedom of expression, and overall functioning of the copyright system. By adapting the long-standing cover license for the mashup genre, Congress can support a charismatic new genre while affording fairer compensation to owners of sampled works, engaging the next generations, and channeling disaffected music fans into authorized markets. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................ 443 I. MUSIC MASHUPS ..................................................................... 446 A. A Personal Journey ..................................................................... 447 † Koret Professor of Law and Director, Berkeley Center for Law & Technology, University of California at Berkeley, School of Law. I thank my sons Dylan and Noah, Peter DiCola, Kembrew McLeod, Gregg Gillis, DJ Guzie, and DJ Solarz for inspiration and background about mashup culture. I also thank Mark Avsec, Jane Ginsburg, Eric Goldman, Molly Van Houweling, David Nimmer, Dotan Oliar, Sean Pager, and participants at the Berkeley Law IP Scholarship Seminar, Berkeley Law Faculty Seminar, and Fifth Annual Internet Law Work-in-Progress Conference for comments. -

TMR Volume 11 15Apr21

TURNING IT UP TO ELEVEN: THE PERILS OF THE LOUDNESS WAR DAN SINGER ocky British rock star Nigel Tufnel (Christopher Guest) and fictitious producer Marty DiBergi (Rob Reiner) are standing in a room filled with C expensive musical equipment. The camera shot switches to a close-up of an amp as the celebrity gloats over its custom volume knob, featuring settings, he emphasizes, that range from one to—not ten, but eleven. The producer is struggling to understand his enthusiasm. “Does that mean it’s…louder? Is it any louder?” he asks. “Well it’s one louder, innit?” declares Tufnel, his British accent dripping with dumb satisfaction. Still not convinced, DiBergi poses the obvious question: “Why don’t you just make ten louder and make ten be the top number?” Tufnel’s smirk evaporates. He pauses, then looks up at the producer: “These go to eleven.” One of the most well-known scenes from the faux-documentary This Is Spinal Tap, this dialogue appeals to us as a classic example of a pop icon so blinded by fame that he is oblivious to his own idiocy. Consumers of pop-culture find it easy to scoff at Tufnel’s enthusiasm and dismiss him as a fame-addled dimwit. But while viewers are busy laughing, what they don’t realize is that they are essentially buying into the same fallacy Tufnel falls victim to through his custom-made amp. Since the decade of the film’s release, the recording industry has been increasingly cranking up its own volume knob on the music it releases. -

These Go to Eleven

These Go to Eleven I have used this quote before but I’m going to recycle it as it is truly one of the all time great movie quotes. The movie, This is Spinal Tap, is a 1984 “rockumentary” (more like a mockumentary) about the world’s loudest band, Spinal Tap. It mocks the intelligence and logic of the stereotypical rock band member. In the scene referenced above, the lead guitar player of the band Spinal Tap, Nigel, shows the interviewer his power amplifier. After showing him the volume goes to eleven, as opposed to the normal maximum ten he says, “if we need that extra push over the cliff, you know what we do?” The answer is obviously “put it up to eleven.” But then the interviewer asks why not just recalibrate ten to make it louder? After a long delay as he thought about the question Nigel answers “These go to eleven.” Clearly, he was totally unable to comprehend the question. This quote is always useful to throw out when somebody says something that makes no sense. While my previous piece, Willful Blindness, focused on narratives that the market gives us that, to be nice, may not be quite right, we will focus here on more broad-based public narratives that are similarly “not quite right,” i.e., they go to eleven. While we at Kopernik always frame discussions around the fact that we are bottom-up stock pickers, I like to look at the big picture (macro) scenario to frame the risk profile. It is from this point of view that I consider the macro picture. -

This Is Spinal Tap Die Jungs Von Spinal Tap Usa 1984

Kieler Beiträge zur Filmmusikforschung, 5.1, 2010 // 95 THIS IS SPINAL TAP DIE JUNGS VON SPINAL TAP USA 1984 R: Rob Reiner. P: Karen Murphy. K: Peter Smokler. S: Kent Beyda, Kim Secrist. T: John Brasher, Beth Bergeron, Douglas B. Arnold, Robert Eber. D: Christopher Guest (Nigel Tufnel), Michael McKean (David St. Hubbins), Harry Shearer (Derek Smalls), David Kaff (Viv Savage), Rob Reiner (Marty DiBergi), Fran Drescher (Bobbi Flekman), Tony Hendra (Ian Faith), June Chadwick (Jeanine Pettibone). DVD-/Video-Vertrieb: MGM Home Entertainment. UA: 2.3.1984 (USA). DVD-Auslieferung: 8.7.1998 (USA), 15.3.1999 (Westeuropa, Japan, Südafrika). 83 min, 1,70:1, Farbe, Dolby. „I wanted to capture the sights, the sounds, the smells, of a hard-working rock band on the road. And I got that. But I got more, a lot more.” Mit diesen Worten leitet Regisseur Rob Reiner, der später für Filme wie HARRY UND SALLY und die oscarprämierte [1] Stephen-King-Verfilmung MISERY verantwortlich war, in seiner Rolle als Dokumentarfilmer Marty DiBergi THIS IS SPINAL TAP ein. Der Film ist eine so genannte Mockumentary, eine komödiantisch-parodistische Pseudo-Dokumentation, über die fiktive Metalband Spinal Tap. Der Plot ist simpel: Eine eher erfolglose britische Band begibt sich auf US-Tour, zerbricht während dieser an diversen selbst- und fremdverschuldeten Problemen und feiert am Ende ihre durch kommerziellen Erfolg in Japan gekrönte Wiedervereinigung. Vor diesem Hintergrund werden die allgegenwärtigen Unannehmlichkeiten im Leben einer Rockband gezeigt: Die Plattenfirma findet das Coverdesign des neuen Albums zu anstößig und veröffentlicht es deshalb mit komplett schwarzem Cover (womit reale Bands wie Metallica und AC/DC durchaus Erfolg hatten), Konzerte werden abgesagt und es kommt zu peinlichem Pannen auf der Bühne. -

A Study of Guitar Hero and Rockband: Why People Play Them and How Marketers Can Use This Information

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 2010-04-21 Turn It Up to Eleven: A Study of Guitar Hero and RockBand: Why People Play Them and How Marketers Can Use This Information Timothy J. Hemingway Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the Communication Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Hemingway, Timothy J., "Turn It Up to Eleven: A Study of Guitar Hero and RockBand: Why People Play Them and How Marketers Can Use This Information" (2010). Theses and Dissertations. 2112. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/2112 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. “Turn It Up to Eleven” A study of Guitar Hero and Rock Band: Why people play, and how marketers can use this information Timothy J. Hemingway A thesis submitted to the faculty of Brigham Young University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts John Davies - Committee Chair Mark Callister - Committee Member Quint Randle - Committee Member Department of Communications Brigham Young University August 2010 Copyright © 2010 Timothy J. Hemingway All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT “Turn It Up to Eleven” A study of Guitar Hero and Rock Band: Why people play, and how marketers can use this information Timothy J. Hemingway Department of Communications Master of Arts This thesis seeks to first understand why individuals play Guitar Hero and Rock Band. -

When Grace Turns Your Heart up to 11” 2 Corinthians 8:1-7 20 June 2021

“When Grace Turns Your Heart Up To 11” 2 Corinthians 8:1-7 20 June 2021 If you know anything about guitar amplifiers, then you know that they only go up to 10. All the knobs only go up to 10. So, the maximum volume level is 10. And, if you know anything about the movie This Is Spinal Tap, then you know that one scene where Nigel, the guitarist, explains that his guitar amplifier actually goes up to 11. * INSERT GUITAR AMP 11 PIC Here’s the dialogue as Nigel explains to Marty, the documentary filmmaker, how the band’s amplifiers all go up to 11: Nigel Tufnel: The numbers all go to eleven. Look, right across the board, eleven, eleven, eleven and... Marty DiBergi: Oh, I see. And most amps go up to ten? Nigel: Exactly. Marty: Does that mean it's louder? Is it any louder? Nigel: Well, it's one louder, isn't it? It's not ten. You see, most, most blokes, you know, will be playing at ten. You're on ten here, all the way up, all the way up, all the way up, you're on ten on your guitar. Where can you go from there? Where? Marty: I don't know. Nigel: Nowhere. Exactly. What we do is, if we need that extra push over the cliff, you know what we do? Marty: Put it up to eleven. Nigel: Eleven. Exactly. One louder. Marty: Why don't you just make ten louder and make ten be the top number and make that a little louder? Nigel: [there’s a long pause] These go to eleven. -

Warner Independent Pictures and Castle Rock Entertainment

WARNER INDEPENDENT PICTURES and CASTLE ROCK ENTERTAINMENT present a SHANGRI-LA ENTERTAINMENT production DIRECTED BY CHRISTOPHER GUEST WRITTEN BY CHRISTOPHER GUEST & EUGENE LEVY RUNNING TIME: 86MIN FOR PHOTOS: FORMAT: 35MM WWW.WARNERINDEPENDENT.COM/PUB ASPECT RATIO: 1:85 USER ID: PRESS SOUND: QUAD PASSWORD: WBPHOTOS RATING: PG-13 LOS ANGELES NEW YORK MICHAEL LAWSON CHRISTINE RICHARDSON MPRM PUBLIC RELATIONS JEREMY WALKER & ASSOCIATES 5670 Wilshire Suite 2500 160 West 71st St, #2-A Los Angeles, CA 90036 New York, NY 10023 323.933.3399 212.595.6161 [email protected] [email protected] SYNOPSIS Christopher Guest turns the camera on Hollywood in For Your Consideration. The film focuses on the making of an independent movie and its cast who become victims of the dreaded awards buzz. Like Guest's previous films, Waiting For Guffman, Best In Show and A Mighty Wind, this latest project features performances from his regular ensemble, including co-writer Eugene Levy. The cast includes Carrie Aizley, Bob Balaban, Ed Begley, Jr., Jennifer Coolidge, Paul Dooley, Ricky Gervais, Christopher Guest, Rachael Harris, John Michael Higgins, Michael Hitchcock, Don Lake, Eugene Levy, Jane Lynch, Michael McKean, Larry Miller, Christopher Moynihan, Catherine O'Hara, Jim Piddock, Parker Posey, Harry Shearer, Deborah Theaker, Fred Willard and Scott Williamson. The film is directed by Christopher Guest, written by Christopher Guest & Eugene Levy and produced by Karen Murphy. For Your Consideration is a Shangri-La Entertainment production presented by Warner Independent Pictures and Castle Rock Entertainment. 2 LONG SYNOPSIS Debut feature director Jay Berman (Christopher Guest), steers cast and crew through a typically tumultuous independent film Home for Purim, an intimate period drama about a Jewish family’s turbulent reunion on the occasion of the dying matriarch’s favorite holiday. -

This Is Spinal Tap Script V

This is Spinal Tap 1 This is Spinal Tap Script v. 4.1 (Nit-picker’s edition :) April 1996 Steve Paget ([email protected]) has done a great job brushing up version 4 of the script, which was originally completed by Svein I. It has been corrected and proof-read (twice!) by Michael Wheeler ([email protected]) and Scott Hagberg ([email protected]), with additional help from the guys at alt.fan.Spinal-Tap. In v 4.1 I’ve corrected some names and added a few lines. If you have any comments, corrections, Tap anecdotes or Close Encounters of the Tap Kind to share, do not hesitate to drop me a line... Svein I. Halvorsen ([email protected]) Keeper of the script to This is Spinal Tap Please keep this header if you are re-distributing the script. This is S P I N A L T A P A Rockumentary by Martin DiBergi <Film Studio> MARTY: Hello. My name is Marty DiBergi. I’m a film maker. I make a lot of commercials. That little dog that chases the covered wagon underneath the sink? That was mine. In 1966, I went down to Greenwich Village, New York City to a rock club called the Electric Banana. Don’t look for it, it’s not there anymore. But that night I heard a band that for me redefined the word “rock and roll”. I remember being knocked out by their, their exuberance…their raw power — and their punctuality. That band was Britain’s now-legendary Spinal Tap. -

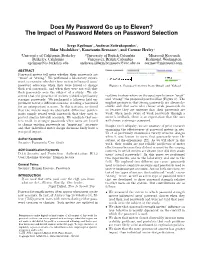

Does My Password Go up to Eleven? the Impact of Password Meters on Password Selection

Does My Password Go up to Eleven? The Impact of Password Meters on Password Selection Serge Egelman1, Andreas Sotirakopoulos2, Ildar Muslukhov2, Konstantin Beznosov2, and Cormac Herley3 1University of California, Berkeley 2University of British Columbia 3Microsoft Research Berkeley, California Vancouver, British Columbia Redmond, Washington [email protected] andreass,ildarm,[email protected] [email protected] ABSTRACT Password meters tell users whether their passwords are \weak" or \strong." We performed a laboratory experi- ment to examine whether these meters influenced users' password selections when they were forced to change Figure 1. Password meters from Gmail and Yahoo! their real passwords, and when they were not told that their passwords were the subject of a study. We ob- served that the presence of meters yielded significantly realtime to show where on the spectrum between \weak" stronger passwords. We performed a followup field ex- and \strong" the proposed password lies (Figure 1). The periment to test a different scenario: creating a password implicit premise is that strong passwords are always de- for an unimportant account. In this scenario, we found sirable and that users who choose weak passwords do that the meters made no observable difference: partici- so because they are unaware that their passwords are pants simply reused weak passwords that they used to weak; when made aware of weak passwords through a protect similar low-risk accounts. We conclude that me- meter's feedback, there is an expectation that the user ters result in stronger passwords when users are forced will choose a stronger password. to change existing passwords on \important" accounts Despite their ubiquity, we are unaware of prior research and that individual meter design decisions likely have a examining the effectiveness of password meters in situ.