The Tuktu and Nogak Project ¥ 381

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EXPERIENCES 2021 Table of Contents

NUNAVUT EXPERIENCES 2021 Table of Contents Arts & Culture Alianait Arts Festival Qaggiavuut! Toonik Tyme Festival Uasau Soap Nunavut Development Corporation Nunatta Sunakkutaangit Museum Malikkaat Carvings Nunavut Aqsarniit Hotel And Conference Centre Adventure Arctic Bay Adventures Adventure Canada Arctic Kingdom Bathurst Inlet Lodge Black Feather Eagle-Eye Tours The Great Canadian Travel Group Igloo Tourism & Outfitting Hakongak Outfitting Inukpak Outfitting North Winds Expeditions Parks Canada Arctic Wilderness Guiding and Outfitting Tikippugut Kool Runnings Quark Expeditions Nunavut Brewing Company Kivalliq Wildlife Adventures Inc. Illu B&B Eyos Expeditions Baffin Safari About Nunavut Airlines Canadian North Calm Air Travel Agents Far Horizons Anderson Vacations Top of the World Travel p uit O erat In ed Iᓇᓄᕗᑦ *denotes an n u q u ju Inuit operated nn tau ut Aula company About Nunavut Nunavut “Our Land” 2021 marks the 22nd anniversary of Nunavut becoming Canada’s newest territory. The word “Nunavut” means “Our Land” in Inuktut, the language of the Inuit, who represent 85 per cent of Nunavut’s resident’s. The creation of Nunavut as Canada’s third territory had its origins in a desire by Inuit got more say in their future. The first formal presentation of the idea – The Nunavut Proposal – was made to Ottawa in 1976. More than two decades later, in February 1999, Nunavut’s first 19 Members of the Legislative Assembly (MLAs) were elected to a five year term. Shortly after, those MLAs chose one of their own, lawyer Paul Okalik, to be the first Premier. The resulting government is a public one; all may vote - Inuit and non-Inuit, but the outcomes reflect Inuit values. -

JWA Single-Sided Report Template

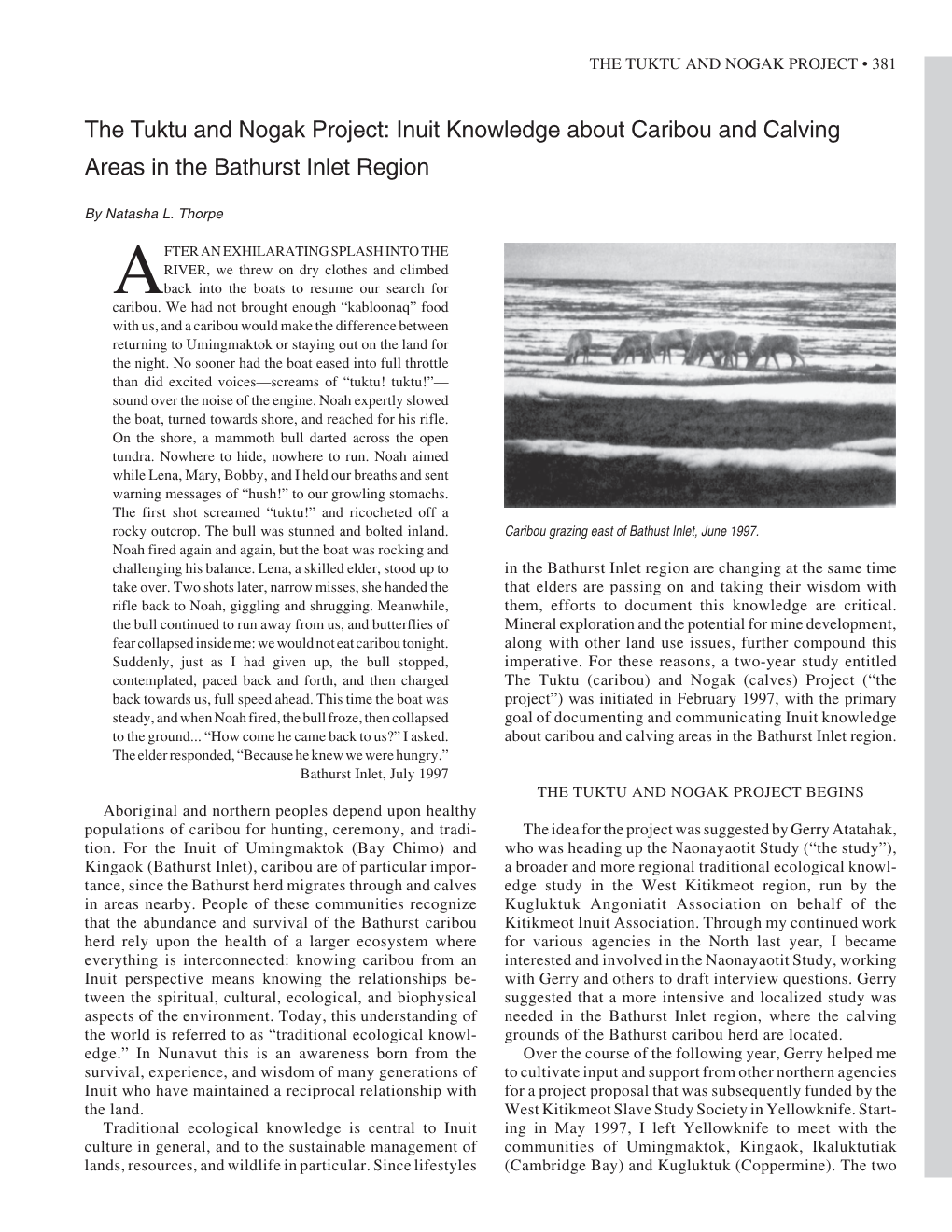

Nunavut Wildlife Resource and Habitat Values Amendment APPENDIX B Figures of Wildlife Habitat 160°0'0"W 150°0'0"W 140°0'0"W 130°0'0"W 120°0'0"W 110°0'0"W 100°0'0"W 90°0'0"W 80°0'0"W 70°0'0"W 60°0'0"W 50°0'0"W 40°0'0"W 30°0'0"W 20°0'0"W GREENLAND Alert ! Hudson U.S.A. Bay Qikiqtani ARCTIC Qu Sanikiluaq Area 1 OCEAN ! Nunavut, Canada NUNAVUT Figure 4.1-1 Ringed Seal Range and CANADA Area 2 70°0'0"N Important Habitat in Nunavut 1 U.S.A. Common in Summer 1 Area of Detail Common in Winter and Pupping Habitat James Base Features Bay Ontario ! Community Road Conservation Area Area 2 Lakes / River Nunavut Regional Boundary National Park !Grise Fiord Migratory Bird Sanctuary M ' C National Wildlife Area l u r e S t Baffin r GREENLAND Beaufort a i t Resolute Bay ! Sea un d So L a n ca st e r 70°0'0"N Arctic Bay ! ! Pond Inlet M ' C D l i ! n Clyde River a 1:11,000,000 t o c Qikiqtani v k 10050 0 100 200 300 400 C i h a Kilometres n s n Gulf e ! Prepared By: l of Qikiqtarjuaq Igloolik Nunami-Stantec ! Tal oyo ak Boothia S ! Hall Beach !Cambridge Bay ! References: ! !Pangnirtung t Gjoa Haven 1 Kugluktuk ! ! Stephenson, S.A. and Hartwig, L (Eds.). 2010. The Arctic Marine Kugaaruk r Workshop. -

Submission to The

SUBMISSION TO THE NUNAVUT WILDLIFE MANAGEMENT BOARD FOR Information: Decision: X Issue: Bathurst Inlet Emerging Char Fishery Application Background: The Burnside Hunters and Trappers Organization (HTO) have requested exploratory licences for Burnside Bay (also known as Swan Lake), Huikitak River, and Burnside River within the Bathurst Inlet area. The HTO has been working closely with Boyd Warner of Bathurst Inlet Lodge Ltd. for the logistical planning associated with the development of these fisheries. Both parties have previously held exploratory licences for the three waterbodies of interest (Table 1). According to the applications and previous correspondence with the applicants there is currently very little subsistence fishing that takes place at the waterbodies of interest. However, past information has indicated that Arctic Char in the Hiukitak River were previously harvested by both Bathurst Inlet and Umingmaktok residents. Previous correspondence with the applicants has also indicated that they are not looking at a “huge scale operation” and that “likely 10,000 lbs [4536 kg] would make things feasible.” Table 1- Burnside Bay, Huikitak River, and Burnside River Licencing History. Maximum Previous Years Licences Were Waterbody Coordinates Exploratory Previously Issued Harvest Level (kg) Burnside Bay/Swan 66°47’N 2000 1989/90-1991/92, Lake (CB 177) 108°10’W 1993/94, 2003/04 Hiukitak River (CB163) 67°08’N 2000 1988/89, 1989/90, 107°10’W 2003/04 Burnside River 66°50’N 2000 1984/85, 1985/86, (CB158) 108°10’W 1988/89-1990/91, 2003/04 Burnside Bay/Swan Lake (66°47’N 108°10’W); Hiukitak River (67°08’N 107°10’W); & Burnside River (66°50’N 108°10’W): Fisheries and Oceans (DFO) - Science advice remains unchanged from 2003/04 for these waterbodies. -

TALOYOAK March 20-21, 2014

Summary of Community Meetings on the Draft Nunavut Land Use Plan TALOYOAK March 20-21, 2014 Revised - May 2014 Contents Introduction ..............................................................................................................................3 Appendix 1: Open House ................................................................................................ 17 1.1 Context ............................................................................................................................ 3 Appendix 2: Elected Officials Meeting...................................................................... 18 1.2 Purpose ............................................................................................................................ 3 Appendix 3: Questions and Answers ........................................................................ 19 1.3 Methodology................................................................................................................. 3 Appendix 4: Community Workshop Scanned Maps .......................................... 20 1.4 Public Awareness ........................................................................................................ 3 Appendix 5: Follow-up Meeting .................................................................................. 31 1.5 Community Population and Participation........................................................ 3 Protecting and Sustaining the Environment ............................................................4 2.1 Areas -

Arctic Science Day

Arctic Science Day An Introduction to Arctic Systems Science Research Conducted at the Centre for Earth Observation Science (U of MB) Produced by: Michelle Watts Schools on Board Program Coordinator Arctic Geography – a brief introduction The Arctic Region is the region around the North Pole, usually understood as the area within the Arctic Circle. It includes parts of Russia, Scandinavia, Greenland, Canada, Alaska and the Arctic Ocean. The Arctic is a single, highly integrated system comprised of a deep, ice covered and nearly isolated ocean surrounded by the land masses of Eurasia and North America. It is made up of a range of land-and seascapes from mountains and glaciers to flat plains, from coastal shallows to deep ocean basins, from polar deserts to sodden wetlands, from large rivers to isolated ponds. Sea ice, permafrost, glaciers, ice sheets, and river and lake ice are all characteristic parts of the Arctic’s physical geography (see circumpolar map) Inuit Regions of Canada (www.itk.ca) Inuit Regions of Canada – See Map Inuit Nuanagat There are four Inuit regions in Canada, collectively known as Inuit Nunangat. The term “Inuit Nunangat” is a Canadian Inuit term that includes land, water, and ice. Inuit consider the land, water, and ice, of our homeland to be integral to our culture and our way of life. Inuvialuit (Northwest Territories) The Inuvialuit region comprises the northwestern part of the Northwest Territories. In 1984, the Inuvialuit, federal and territorial governments settled a comprehensive land claims agreement, giving Inuvialuit surface and subsurface (mining) rights to most of the region. The Agreement ensures environmental protection, harvesting rights and Inuvialuit participation and support in many economic development initiatives. -

Bathurst Inlet Port and Road Project Baseline Marine Mammal Studies

Bathurst Inlet Port and Road Project Baseline Marine Mammal Studies, September 2004 prepared by environmental research associates for Bathurst Inlet Port and Road Joint Venture 340 Park Place, 666 Burrard Street Vancouver, BC V6C 2X8 LGL Report TA4079-1 June 2005 Bathurst Inlet Port and Road Project Baseline Marine Mammal Studies, September 2004 prepared by Ross Harris, Ted Elliott, and William E. Cross LGL Limited, environmental research associates 22 Fisher St., POB 280 King City, ON L7B 1A6 for Bathurst Inlet Port and Road Joint Venture 340 Park Place, 666 Burrard Street Vancouver, BC V6C 2X8 LGL Report TA4079-1 June 2005 Table of Contents Table of Contents Executive Summary......................................................................................................................................v 1. Introduction..............................................................................................................................................1 1.1 Background........................................................................................................................................1 1.2 Objectives ..........................................................................................................................................1 2. Methods ...................................................................................................................................................1 2.1 Survey Design....................................................................................................................................1 -

Natural Resource Development and Infrastructure Projects in the North

NorthernNorthern ProjectsProjects ManagementManagement OfficeOffice CanNor ! !AlertAlert i NaturalNatural Resource Resource Development Development andand Infrastructure Infrastructure Projects Projects ii LegendLegend in thein the Yukon, Yukon, Northwest Northwest Territories and and Nunavut Nunavut i Operating MineMine Natural Resource Project TheThe Northern Northern Projects Projects Management Management OfficeOffice (NPMO),(NPMO), asas partpart of ofthe the Natural Resource Project CanadianCanadian Northern Northern Economic Economic Development Development AgencyAgency (CanNor), (CanNor), advances advances Highway Project northernnorthern resource resource development development by providingproviding issues issues management, management, Capital path-findingpath-finding and and advice advice to to industry industry and communities; coordinates coordinates the the Community northernnorthern regulatory regulatory responsibilities responsibilities ofof federal departments; departments; and an publiclyd publicly trackstracks the the progress progress of of projects projects toto bring transparency,transparency, timeliness timeliness and and ThisThis map map represents represents operatingoperating mines mines effectivenesseffectiveness to to thethe regulatory system. system. andand projects projects that that havehave entered the the environmentalenvironmental assessment assessment phase, phase, as wellas ForFor more more information information please contactcontact us us at at wellas projects as projects that are that expected are -

Meadowbank Gold Project

0 200000 400000 600000 800000 1000000 Taloyoak Cambridge Bay King William Island Kugaaruk Gjoa Haven 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 t 0 0 0 6 Rasmussen 6 7 Queen Maud Adelaide 7 Gulf McLoughlin Peninsula Basin Umingmaktok Bay Chantrey Inlet Bathurst Inlet Naujaat 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 4 4 7 7 Nunavut 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 2 2 7 7 Baker Lake 0 0 0 Northwest 0 0 0 0 0 0 Rankin Inlet 0 0 Territories 0 7 7 H ud so n Bay 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Arviat 0 8 8 6 6 Ar ea of De t a il Saskatchewan 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 6 6 6 Manitoba 6 2019 Satellite-collared Caribou by Season Churchill G Spring G Fall . G Summer G Winter 0 200000 400000 600000 800000 1000000 Legend 0 50 100 150 Figure 6.1: 2019 Government of All-Weather Access Road Kilometres Nunavut and Northwest Territories Whale Tail Haul Road Meadowbank All-Weather Access Road Local Study Area (LSA) Projection: UTM Zone 14 NAD83 Telemetry Programs Collar Locations Meadowbank Local Study Area (LSA) Data Sources: Meadowbank Regional Study Area (RSA) Natural Resources Canada, GeoBase® Meadowbank Gold Project Whale Tail Pit and Haul Road Local Study Area (LSA) National Topographic Database, Prepared for: By: Agnico-Eagle Mines Limited, Whale Tail Pit and Haul Road Regional Study Area (RSA) Department of Environment (Gov't of Nunavut), Gov't of Northwest Territories 600000 650000 t Whale Tail 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 5 5 2 2 7 7 Vault Meadowbank 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 2 Tehek 2 7 Lake 7 Schultz Lake T h e l o n R i v e r Whitehills Lake 0 0 0 Ar ea of D e tai l 0 0 0 0 0 5 5 1 1 7 7 Bak er Lak e 2019 Satellite-collared Caribou by Season -

Publications in Biological Oceanography, No

National Museums National Museum of Canada of Natural Sciences Ottawa 1971 Publications in Biological Oceanography, No. 3 The Marine Molluscs of Arctic Canada Elizabeth Macpherson CALIFORNIA OF SCIK NCCS ACADEMY |] JAH ' 7 1972 LIBRARY Publications en oceanographie biologique, no 3 Musees nationaux Musee national des du Canada Sciences naturelles 1. Belcher Islands 2. Evans Strait 3. Fisher Strait 4. Southampton Island 5. Roes Welcome Sound 6. Repulse Bay 7. Frozen Strait 8. Foxe Channel 9. Melville Peninsula 10. Frobisher Bay 11. Cumberland Sound 12. Fury and Hecia Strait 13. Boothia Peninsula 14. Prince Regent Inlet 15. Admiralty Inlet 16. Eclipse Sound 17. Lancaster Sound 18. Barrow Strait 19. Viscount Melville Sound 20. Wellington Channel 21. Penny Strait 22. Crozier Channel 23. Prince Patrick Island 24. Jones Sound 25. Borden Island 26. Wilkins Strait 27. Prince Gustaf Adolf Sea 28. Ellef Ringnes Island 29. Eureka Sound 30. Nansen Sound 31. Smith Sound 32. Kane Basin 33. Kennedy Channel 34. Hall Basin 35. Lincoln Sea 36. Chantrey Inlet 37. James Ross Strait 38. M'Clure Strait 39. Dease Strait 40. Melville Sound 41. Bathurst Inlet 42. Coronation Gulf 43. Dolphin and Union Strait 44. Darnley Bay 45. Prince of Wales Strait 46. Franklin Bay 47. Liverpool Bay 48. Mackenzie Bay 49. Herschel Island Map 1 Geographical Distribution of Recorded Specimens CANADA DEPARTMENT OF ENERGY, MINES AND RESOURCES CANADASURVEYS AND MAPPING BRANCH A. Southeast region C. North region B. Northeast region D. Northwest region Digitized by tlie Internet Archive in 2011 with funding from California Academy of Sciences Library http://www.archive.org/details/publicationsinbi31nati The Marine Molluscs of Arctic Canada Prosobranch Gastropods, Chitons and Scaphopods National Museum of Natural Sciences Musee national des sciences naturelles Publications in Biological Publications d'oceanographie Oceanography, No. -

Northern Canadian Sealift Delivery Northern Exposure 2 Conference, Transport Institute, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, March 2013

Northern Canadian Sealift Delivery Northern Exposure 2 Conference, Transport Institute, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, March 2013 François Gaudreau Outline - Who are we? - What are we doing? - In what kind of environment? - In what kind of changing environment? Who are we? Nunavut Nunavik -Our main Ports of loading are Ste. Catherine, Bécancour and Churchill; -Our Operations Management Office is located in Ste. Catherine, on the St-Lawrence Seaway; -We have other offices in Iqaluit, Rankin Inlet and Winnipeg; -Our clients are Governments, Government Agencies; General Contractors, Contractors, Mining Companies, Freight Forwarders, Individuals. -NSSI was incorporated in 2000; -Maritime transportation service provider for 25 Nunavut communities and numerous Mining and remote sites; -Government of Nunavut designated Maritime Carrier for 24 communities and 2 summer sites (Umingmaktok and Kingaok); -TTI was incorporated in 2007; -Maritime transportation service provider for all 14 Nunavik communities, Mining and remote sites; What are we exactly doing? What kind of cargo? Our Core Fleet Claude A. Desgagnés -20 000 m3; -2 x 150 MT Cranes; -Built in 2011. Zélada Desgagnés -20 000 m3; -2 x 180 MT Cranes; -Built in 2009. Sedna Desgagnés -20 000 m3; -2 x 180 MT Cranes; -Built in 2009. Rosaire A. Desgagnés -20 000 m3; -2 x 120 MT Cranes; -Built in 2007. Anna Desgagnés -24 000 m3; -7 Cranes-Derrick; -Built in 1986. Camilla Desgagnés -16 000 m3; -1 x 50 MT Crane; -Built in 1982. In what kind of Environment? -Up North, mostly North of the 60 th parallel; -

Data Summary and Analysis of the Wolverine Harvest from Kugluktuk, Umingmaktok and Bathurst Inlet, Northwest Territories 1985/86-1996/97

Database Description, Data Summary and Analysis of the Wolverine Harvest from Kugluktuk, Umingmaktok and Bathurst Inlet, Northwest Territories 1985/86-1996/97 John Lee Environment and Natural Resources, Service Contract 335448 2016 Manuscript Report No. 253 The contents of this report are the sole responsibility of the author. ii ABSTRACT This report describes the data standards and data format for harvest information collected from a wolverine harvest in the Central Arctic from 1985-1997. It comments on the intention behind variables selected and provides a brief summary and analysis of some of the data collected. The harvest ranged from the west shore of Great Bear Lake to the east end of Kent peninsula, and to the south end of Contwoyto Lake. Over the eleven years covered by the collection, 822 wolverines were recorded harvested. Eighty-one percent were hunted, while just 18% were trapped. Sex ratio (M:F) of the overall harvest was 1.87, while the sex ration of the trapped animals was close to 1:1. Younger animals made up a significant part of the harvest with the average age of males and females 1.5 and 1.7 years respectively. The maximum age recorded was an 11 year old female. Counts of corpora lutea from adult females resulted in an in vivo litter size of 3.46. Some options for indexing harvest intensities are considered. iii Table of Contents ABSTRACT ................................................................................................................................... iii LIST OF FIGURES ....................................................................................................................... -

Kugluktuk Bathurst Inlet Kingaok Bay

P.O. Box 360 Kugluktuk, NU X0B 0E0 Telephone: (867) 982-3310 Fax: (867) 982-3311 www.kitia.ca February 3, 2015 Kugluktuk Canadian High Arctic Research Station P.O Box ᖁᕐᓗᖅᑐᖅ Cambridge Bay, NU X0B 0C0 Bathurst Inlet Via Email: Kingaok ᕿᙵᐅᓐ Re: Letter of Support for Drs. Jennifer Galloway and Tim Patterson research project - Geoscience Tools for Supporting Environmental Risk Assessment of Metal Mining Bay Chimo Umingmaktok Dear Proposal Reviewer: ᐅᒥᖕᒪᒃᑑᖅ The mandate of the Kitikmeot Inuit Association (KIA) is “to represent the interests of Kitikmeot Inuit by protecting and promoting our social, cultural, political, environmental and economic well- Cambridge Bay being.” As such, the KIA promotes sustainable development benefiting our people, our region, and our territory. Currently, however, regional geochemical baseline data is very limited in the Ikaluktutiak Arctic, and this restricts the ability to develop the most appropriate monitoring guidelines and ᐃᖃᓗᒃᑑᑦᑎᐊᖅ remediation targets for land development. The KIA supports the proposal submitted by Drs. Jennifer Galloway and Tim Patterson for several Gjoa Haven reasons. Firstly, the proposal addresses critical knowledge gaps regarding climate change and Okhoktok baseline geochemistry in the Slave Geological Province. Secondly, once understood, these gaps have the potential to facilitate the translation of new data and the development of geoscience ᐅᖅᓱᖅᑑᖅ tools to inform and support decision-makers. We are particularly pleased that the proposed research is planned in the vicinity of the Hope Bay project as this will help establish pre- development geochemical baseline for this region of high resource potential. Taloyoak ᑕᓗᕐᔪᐊᕐᒃ The KIA is pleased that the team includes federal, territorial, community, industry, academic, First Nations, and Inuit collaborators.