The Abolishment of the Non-Entertaining Programming Requirement and the State of Radio News: Effects on Tennessee's Major Markets Since 1985

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Promoter and Event Planning Guide

YOUR SEAT IS WAITING. PROMOTER AND EVENT PLANNING GUIDE 500 Howard Baker Jr. Avenue, Knoxville, TN 37915 | Phone: (865) 215-8900 www.knoxvillecoliseum.com Thank you for considering Knoxville as the WELCOME destination for your event or show. The Knoxville Civic Auditorium and Coliseum (KCAC) is a multipurpose event venue owned by the City of Knoxville and managed by SMG, the recognized global industry leader in public assembly facility management. The venue features several options for entertainment. The Coliseum is the largest space and seats more than 6,500 for concerts and public events. The Auditorium’s 2,500 seats allow for a more intimate experience for performances. A 10,000-square-foot exhibit hall, 4,800-square- foot reception hall and outdoor performance lawn with capacity for 10,000 guests also are available at the KCAC. You will receive the highest level of customer service to ensure the event is a success in the space that best suits your needs. This Promoter and Event Planning Guide is designed as a handbook for holding an event at our facility by providing information about services, guidelines and event-related topics. You will be contacted by the event management team member assigned to your event. The event manager will be available throughout the planning process to answer questions and provide assistance. The event manager will provide a cost estimate associated with the event, assist with development of floor plans, provide lists of preferred vendors and personally supervise your event from the first day through its conclusion. Thank you again for considering the KCAC for your event. -

TN-CTSI Research Study Recruitment Resources

RESEARCH STUDY RECRUITMENT RESOURCES UTHSC Electronic Data Warehouse 901.287.5834 | [email protected] | cbmi.lab.uthsc.edu/redw The Center for Biomedical Informatics (CBMI) at UTHSC has developed Research Enterprise Data Warehouse (rEDW) – a standardized aggregated healthcare data warehouse from Methodist Le Bonheur Health System. Our mission is to develop a single, comprehensive and integrated warehouse of all pediatric and adult clinical data sources on the campus to facilitate healthcare research, healthcare operations and medical education. The rEDW is an informatics tool available to researchers at UTHSC and Methodist Health System to assist with generating strong, data-driven hypotheses. Via controlled searches of the rEDW, UTHSC researchers will have the ability to run cohort queries, perform aggregated analyses and develop evidenced preparatory to research study plans. ResearchMatch.org The ResearchMatch website is a web-based tool that was established as a unique collaborative effort with participating sites in the NIH Clinical and Translational Science Awards Consortium and is hosted by Vanderbilt University. UTHSC is a participating ResearchMatch (RM) is a registry allowing anyone residing in the United States to self-register as a potential research participant. Researchers can register their studies on ResearchMatch after IRB approval is granted. The ResearchMatch system employs a ‘matching’ model – Volunteers self-register and Researchers search for Volunteers for their studies. Social Media Facebook — Form and info to advertise -

Emergency Response Plan

EMERGENCY RESPONSE PLAN March 2009 (2018 Revision pending review and approval) ROANE STATE COMMUNITY COLLEGE EMERGENCY RESPONSE PLAN GUIDELINE INDEX Section Page I. Purpose ……………………………………………………………………….. 3 II. Emergency Defined A. Minor Emergency ………………………………………………………... 4 B. Major Emergency ………………………………………………………... C. 4 Building Evacuation……………………………………………………… 4 D. Disaster…………………………………………………………………... 4 III. Procedures of Emergency Response Plan 1. Initial Response Plan ……………………………………………………... 5 2. Declaration of Emergency and Activation of Emergency Response Plan... 5 3. Emergency Operations Center …………………………………………… 4. 6 Command Post …………………………………………………………… 6 5. Emergency Management Response Team (EMRT) ……………………... 7 6. Evacuations ………………………………………………………………. 7 7. Shelters …………………………………………………………………… 8 8. News Media ……………………………………………………………… 9. 8 Volunteer Management ………………………………………………….. 9 10. Purchasing Guidelines 9 …………………………………………………… 9 11. Transportation Services 9 ………………………………………………….. 12. Lines of Communication 10 ………………………………………………… 10 13. Documentation of Activities …………………………………………….. 14. Campus Maps and Building Prints ……………………………………… 10 15. Distressed, Disturbed, Disruptive & Dangerous Students: Student Assistance Coordinating Committee (Threat Assessment Team)……….. 10 16. Distressed, Disturbed, Disruptive & Dangerous Students: Faculty & Staff 11 Training …………………………………………………………………. 11 17. Maintenance of Emergency Response Plan …………………………….. 18. Emergency Response Plan Training ……………………………………. Page 1 APPENDICES Page A EMRT Administrators -

69 Knoxville

GM: Patrick McCurrin GSM: Patrick McCurrin Rep: Katz Net: ABC -E #149 Killeen -Temple TX PD: Patrick McCurrin CE: Steve Sullivan Dick Broadcasting Inc. (grp) 12+ Population: 243,600 Net: Focus, USA 6711 Kingston Pike, Knoxville TN 37919 % Black 19.2 (423) 588 -6511 Fax: (423) 588 -3725 % Hispanic 12.0 KRMY -AM Spanish WIVK -AM News -Talk HH Income $35,095 1050 kHz 250 w -D, ND 990 kHz 10 kw -U, DAN Total Retail (000) $1,633,007 City of license: Killeen TX City of license: Knoxville GM: Eugene Kim GSM: Stephanie Kim GSM: Jim Christenson PD: Mike Hammond PD: Marti Martinez CE: Jerry White Market Revenue (millions) Martin Broadcasting Group 1994: $4.69 314 N. 2nd St., Killeen TX 76541 WJBZ-FM Religion 1995: $4.98 (817) 628-7070 Fax: (817) 628 -7071 96.3 mHz 1.19 kw, 479' 1 996: $5.31 City of license: Seymour TN 1997: $5.56 #69 Knoxville GM: Charlotte Mull GSM: Charlotte Mull 1998: $5.92 12+ PD: Charlotte Mull CE: Milton Jones estimates provided by Radio Population: 547,400 Black 5.9 Seymour Communications Research Development Inc. % Hispanic 0.5 Box 2526, Knoxville TN 37901 HH Income $37,822 7101 Chapman Hwy.; 37920 Station Cross- Reference Total Retail (000) $6,251,017 (423) 577 -4885 Fax: On Request KITZ -FM - KOOV -FM KKIK -FM - KRMY -AM - KLFX-FM KITZ -FM KTEM -AM KKIK -FM Market Revenue (millions) Duopoly KLTX -FM KITZ -FM KTON -AM KOOV -FM 1994: $20.11 KOOC -FM KOOV -FM 1995: $21.72 WJXB -FM AC 1996: $23.46 97.5 mHz 100 kw, 1,295' 1997: $25.06 City of license: Knoxville Duopoly 1998: $27.07 GM: Craig Jacobus GSM: Jim Ridings KIIZ -FM Urban estimates provided by Radio PD: Jeff Jarnigan CE: Bob Glen 92.3 mHz 3 kw, 259' Research Development Inc. -

WDIA from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

WDIA From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia WDIA City of Memphis, Tennessee license Broadcast Memphis, Tennessee area Branding AM 1070 WDIA Slogan The Heart and Soul of Memphis Frequency 1070 kHz KJMS 101.1 FM HD-2 (simulcast) First air date June 7, 1947 Format Urban Oldies/Classic Soul Power 50,000 watts daytime 5,000 watts nighttime Class B Facility ID 69569 Callsign DIAne, name of original owner's daughter meaning We Did It Again (when owners also launched similar station in Jackson, Mississippi, after World War II) Owner iHeartMedia, Inc. Sister KJMS, WEGR, WHAL-FM, WHRK,WREC stations Under LMA: KWAM Webcast Listen Live Website http://www.mywdia.com/main.html WDIA is a radio station based in Memphis, Tennessee. Active since 1947, it soon became the first radio station in America that was programmed entirely for African Americans.[1] It featured black radio personalities; its success in building an audience attracted radio advertisers suddenly aware of a "new" market among black listeners. The station had a strong influence on music, hiring musicians early in their careers, and playing their music to an audience that reached through the Mississippi Delta to the Gulf Coast. The station started the WDIA Goodwill Fund to help and empower black communities. Owned by iHeartMedia, Inc., the station's studios are located in Southeast Memphis, and the transmitter site is in North Memphis. Contents [hide] • 1 History • 2 References • 3 Further reading • 4 External links History[edit] WDIA went on the air June 7, 1947,[2] from studios on Union Avenue. The owners, John Pepper and Dick Ferguson, were both white, and the format was a mix of country and western and light pop. -

Stations Monitored

Stations Monitored 10/01/2019 Format Call Letters Market Station Name Adult Contemporary WHBC-FM AKRON, OH MIX 94.1 Adult Contemporary WKDD-FM AKRON, OH 98.1 WKDD Adult Contemporary WRVE-FM ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY, NY 99.5 THE RIVER Adult Contemporary WYJB-FM ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY, NY B95.5 Adult Contemporary KDRF-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 103.3 eD FM Adult Contemporary KMGA-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 99.5 MAGIC FM Adult Contemporary KPEK-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 100.3 THE PEAK Adult Contemporary WLEV-FM ALLENTOWN-BETHLEHEM, PA 100.7 WLEV Adult Contemporary KMVN-FM ANCHORAGE, AK MOViN 105.7 Adult Contemporary KMXS-FM ANCHORAGE, AK MIX 103.1 Adult Contemporary WOXL-FS ASHEVILLE, NC MIX 96.5 Adult Contemporary WSB-FM ATLANTA, GA B98.5 Adult Contemporary WSTR-FM ATLANTA, GA STAR 94.1 Adult Contemporary WFPG-FM ATLANTIC CITY-CAPE MAY, NJ LITE ROCK 96.9 Adult Contemporary WSJO-FM ATLANTIC CITY-CAPE MAY, NJ SOJO 104.9 Adult Contemporary KAMX-FM AUSTIN, TX MIX 94.7 Adult Contemporary KBPA-FM AUSTIN, TX 103.5 BOB FM Adult Contemporary KKMJ-FM AUSTIN, TX MAJIC 95.5 Adult Contemporary WLIF-FM BALTIMORE, MD TODAY'S 101.9 Adult Contemporary WQSR-FM BALTIMORE, MD 102.7 JACK FM Adult Contemporary WWMX-FM BALTIMORE, MD MIX 106.5 Adult Contemporary KRVE-FM BATON ROUGE, LA 96.1 THE RIVER Adult Contemporary WMJY-FS BILOXI-GULFPORT-PASCAGOULA, MS MAGIC 93.7 Adult Contemporary WMJJ-FM BIRMINGHAM, AL MAGIC 96 Adult Contemporary KCIX-FM BOISE, ID MIX 106 Adult Contemporary KXLT-FM BOISE, ID LITE 107.9 Adult Contemporary WMJX-FM BOSTON, MA MAGIC 106.7 Adult Contemporary WWBX-FM -

Litefin JANUARY 10, 2003 We Listen to Radio VOLUME 11 NO

THIS WEEK IN MONITOR: WLTW, WBLI Tops In Fall Arbitrons p.41,067 Labels Are Hurting, Does Radio Care? p. 28Litefin JANUARY 10, 2003 We Listen To Radio VOLUME 11 NO. 2SB.95 Welcome To The New Airplay Monitor Usually, an Airplay Monitor reader can count on opening our first magazine of the year and find- ing out what stations around the country changed formats during the holiday season. This year, the format change is ours. For the past 10 years, even the most devoted reader of the Airplay Monitor publications proba- bly wasn't seeing all our best stuff. That's because there were four, very specifically targeted editions of this magazine-serving top 40, R&B, country, and rock-that joined forces only for our year- end special edition and our fifth -anniversary issue. This week, there is one Airplay Monitor that gives programmers all the information they need from all 14 formats we cover. It's the same chart info from Nielsen Broadcast Data Systems that you've trusted for more than a decade. It's the same hard-hitting Monitor journalism that ana- lyzes radio programming and trends like no other publication. Just more of it. The new all -format Airplay Monitor is in recog- nition of the changes that have taken place in our industries in recent years. PDs rarely have the lux- ury of work- ing with only WHAT'S CHANGED one station. or format. More Chart Info anymore. Every Format in One Labels, for Magazine theirpart. New Features now think of almost even WHAT HASN'T projectin Country Radio multi -format BDS Chart Reliability terms. -

Memphis Is a Comprehensive Urban University Committed to Scholarly Accomplishments of Our Students and Faculty and to the Enhancement of Our Community

he University of Memphis is a comprehensive urban university committed to scholarly accomplishments of our students and faculty and to the enhancement of our community. The Uni- versity of Memphis offers 15 bachelor's degrees in more than 50 Tmajors and 70 concentrations, master's degrees in 45 subjects and doctoral degrees in 18 disciplines, in addition to the Juris Doctor (law) and a specialist degree in education. The University of Memphis campus is located on 1,160 acres with nearly 200 buildings at more than four sites. During a typical semester, students come from almost every state and many foreign countries. The average age of full-time undergraduates is 23. The average ACT score for entering freshman is 22. ` Memphis he University of Memphis was founded under the auspices of the General Education Bill, enacted by the Tennessee Legislature in 1909. Known origi- nally as West Tennessee Normal School, the institution opened its doors Sept. 10, 1912, with Dr. Seymour A. Mynders as president. TStudents in the first classes selected blue and gray as the school colors and the Tiger as the mascot. (Tradition holds that the colors, those of the opposing armies during the Civil War, were chosen in commemoration of the reuniting of the country after that divisive conflict.) Over the next decade, The Desoto yearbook was created, the first library was opened in the Administration Building, the first dining hall was built and the first men's dorm was built; today that dorm, Scates Hall, houses the academic counseling offices. In 1925 the name of the college changed to West Tennessee State Teachers Col- lege. -

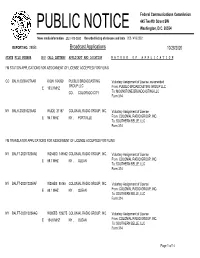

Broadcast Applications 10/28/2020

Federal Communications Commission 445 Twelfth Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media information 202 / 418-0500 Recorded listing of releases and texts 202 / 418-2222 REPORT NO. 29853 Broadcast Applications 10/28/2020 STATE FILE NUMBER E/P CALL LETTERS APPLICANT AND LOCATION N A T U R E O F A P P L I C A T I O N FM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR ASSIGNMENT OF LICENSE ACCEPTED FOR FILING CO BALH-20200427AAR KIQN 164269 PUEBLO BROADCASTING Voluntary Assignment of License, as amended GROUP LLC E 103.3 MHZ From: PUEBLO BROADCASTING GROUP LLC CO , COLORADO CITY To: MOONSTONE BROADCASTING LLC Form 314 NY BALH-20201023AAD WUDE 21197 COLONIAL RADIO GROUP, INC. Voluntary Assignment of License E 96.7 MHZ NY , PORTVILLE From: COLONIAL RADIO GROUP, INC. To: SOUTHERN BELLE, LLC Form 314 FM TRANSLATOR APPLICATIONS FOR ASSIGNMENT OF LICENSE ACCEPTED FOR FILING NY BALFT-20201023AAE W254BQ 146562 COLONIAL RADIO GROUP, INC. Voluntary Assignment of License E 98.7 MHZ NY , OLEAN From: COLONIAL RADIO GROUP, INC. To: SOUTHERN BELLE, LLC Form 314 NY BALFT-20201023AAF W256BS 85145 COLONIAL RADIO GROUP, INC. Voluntary Assignment of License E 99.1 MHZ NY , OLEAN From: COLONIAL RADIO GROUP, INC. To: SOUTHERN BELLE, LLC Form 314 NY BALFT-20201023AAG W285ES 139275 COLONIAL RADIO GROUP, INC. Voluntary Assignment of License E 104.9 MHZ NY , OLEAN From: COLONIAL RADIO GROUP, INC. To: SOUTHERN BELLE, LLC Form 314 Page 1 of 14 Federal Communications Commission 445 Twelfth Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media information 202 / 418-0500 Recorded listing of releases and texts 202 / 418-2222 REPORT NO. -

Public Notice >> Licensing and Management System Admin >>

REPORT NO. PN-2-200720-01 | PUBLISH DATE: 07/20/2020 Federal Communications Commission 445 12th Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media info. (202) 418-0500 ACTIONS File Number Purpose Service Call Sign Facility ID Station Type Channel/Freq. City, State Applicant or Licensee Status Date Status 0000107750 Renewal of FM WAWI 81646 Main 89.7 LAWRENCEBURG, AMERICAN FAMILY 07/16/2020 Granted License TN ASSOCIATION 0000107387 Renewal of FX W250BD 141367 97.9 LOUISVILLE, KY EDUCATIONAL 07/16/2020 Granted License MEDIA FOUNDATION 0000109653 Renewal of FX W270BK 138380 101.9 NASHVILLE, TN WYCQ, INC. 07/16/2020 Granted License 0000107099 Renewal of FM WFWR 90120 Main 91.5 ATTICA, IN FOUNTAIN WARREN 07/16/2020 Granted License COMMUNITY RADIO CORP 0000110354 Renewal of FM WBSH 3648 Main 91.1 HAGERSTOWN, IN BALL STATE 07/16/2020 Granted License UNIVERSITY 0000110769 Renewal of FX W218CR 141101 91.5 CENTRAL CITY, KY WAY MEDIA, INC. 07/16/2020 Granted License 0000109620 Renewal of FL WJJD-LP 123669 101.3 KOKOMO, IN KOKOMO SEVENTH- 07/16/2020 Granted License DAY ADVENTIST BROADCASTING COMPANY 0000107683 Renewal of FM WQSG 89248 Main 90.7 LAFAYETTE, IN AMERICAN FAMILY 07/16/2020 Granted License ASSOCIATION Page 1 of 169 REPORT NO. PN-2-200720-01 | PUBLISH DATE: 07/20/2020 Federal Communications Commission 445 12th Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media info. (202) 418-0500 ACTIONS File Number Purpose Service Call Sign Facility ID Station Type Channel/Freq. City, State Applicant or Licensee Status Date Status 0000108212 Renewal of AM WNQM 73349 Main 1300.0 NASHVILLE, TN WNQM. -

City of Millington Water System

Drought Management Plan For City of Millington Water System PWSID: 0000463 Date: June 30, 2016 Revised: September 29, 2016 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Authority And Status To Plan 3 Purpose Of The Drought Management Plan 3 Drought Management Plan Within The Context Of An EOP 4 The Planning Committee 4 System Characteristics And Risks 4 Goals, Objectives, And Priorities 5 General Water Uses In Order Of Priority 5 Interconnections, Mutual Aid Agreements, And Backup Sources 5 Ordinances, Policies, And Legal Requirements 6 Monitor Supply And Demand 6 Well Static Water Levels 6 Phased Management 6 Public Notification – News Media 7 Drought Alert 7 Voluntary Water Reductions 7 Mandatory Water Restrictions 7 Emergency Water Management 8 Management Team 8 Deactivation 8 Review, Evaluation, And Up-Dating The Management Plan 9 2 Authority and Status to Plan. Under the Authority of the Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation; (TDEC), T.C.A. 68-221-701 Rules of TDEC Division of Water Resources Chapter 0400-45-01-.17, the City of Millington is required to prepare and maintain an Emergency Operations Plan; (EOP), in order to safeguard the water supply and to alert the public of unsafe drinking water in the event of natural or man-made disasters. Emergency Operations Plans shall be consistent with guidelines established, reviewed, and approved by TDEC. The EOP shall include a Drought Management Plan; as part of the EOP. TDEC has granted the City of Millington Board of Mayor and Aldermen the authority to administer and enforce the guidelines set forth in this Drought Management Plan; RESTRICTED USE OF WATER-“in times of emergencies or in times of water shortage, the municipality reserves the right to restrict the purpose for which water may be used by a customer and the amount of water which a customer may use”. -

2021 Iheartradio Music Festival Win Before You Can Buy Flyaway Sweepstakes Appendix a - Participating Stations

2021 iHeartRadio Music Festival Win Before You Can Buy Flyaway Sweepstakes Appendix A - Participating Stations Station Market Station Website Office Phone Mailing Address WHLO-AM Akron, OH 640whlo.iheart.com 330-492-4700 7755 Freedom Avenue, North Canton OH 44720 WHOF-FM Akron, OH sunny1017.iheart.com 330-492-4700 7755 Freedom Avenue, North Canton OH 44720 WHOF-HD2 Akron, OH cantonsnewcountry.iheart.com 330-492-4700 7755 Freedom Avenue, North Canton OH 44720 WKDD-FM Akron, OH wkdd.iheart.com 330-492-4700 7755 Freedom Avenue, North Canton OH 44720 WRQK-FM Akron, OH wrqk.iheart.com 330-492-4700 7755 Freedom Avenue, North Canton OH 44720 WGY-AM Albany, NY wgy.iheart.com 518-452-4800 1203 Troy Schenectady Rd., Latham NY 12110 WGY-FM Albany, NY wgy.iheart.com 518-452-4800 1203 Troy Schenectady Rd., Latham NY 12110 WKKF-FM Albany, NY kiss1023.iheart.com 518-452-4800 1203 Troy Schenectady Rd., Latham NY 12110 WOFX-AM Albany, NY foxsports980.iheart.com 518-452-4800 1203 Troy Schenectady Rd., Latham NY 12110 WPYX-FM Albany, NY pyx106.iheart.com 518-452-4800 1203 Troy Schenectady Rd., Latham NY 12110 WRVE-FM Albany, NY 995theriver.iheart.com 518-452-4800 1203 Troy Schenectady Rd., Latham NY 12110 WRVE-HD2 Albany, NY wildcountry999.iheart.com 518-452-4800 1203 Troy Schenectady Rd., Latham NY 12110 WTRY-FM Albany, NY 983try.iheart.com 518-452-4800 1203 Troy Schenectady Rd., Latham NY 12110 KABQ-AM Albuquerque, NM abqtalk.iheart.com 505-830-6400 5411 Jefferson NE, Ste 100, Albuquerque, NM 87109 KABQ-FM Albuquerque, NM hotabq.iheart.com 505-830-6400