Genome Watchhoney, I Shrunk the Mimiviral Genome

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Changes to Virus Taxonomy 2004

Arch Virol (2005) 150: 189–198 DOI 10.1007/s00705-004-0429-1 Changes to virus taxonomy 2004 M. A. Mayo (ICTV Secretary) Scottish Crop Research Institute, Invergowrie, Dundee, U.K. Received July 30, 2004; accepted September 25, 2004 Published online November 10, 2004 c Springer-Verlag 2004 This note presents a compilation of recent changes to virus taxonomy decided by voting by the ICTV membership following recommendations from the ICTV Executive Committee. The changes are presented in the Table as decisions promoted by the Subcommittees of the EC and are grouped according to the major hosts of the viruses involved. These new taxa will be presented in more detail in the 8th ICTV Report scheduled to be published near the end of 2004 (Fauquet et al., 2004). Fauquet, C.M., Mayo, M.A., Maniloff, J., Desselberger, U., and Ball, L.A. (eds) (2004). Virus Taxonomy, VIIIth Report of the ICTV. Elsevier/Academic Press, London, pp. 1258. Recent changes to virus taxonomy Viruses of vertebrates Family Arenaviridae • Designate Cupixi virus as a species in the genus Arenavirus • Designate Bear Canyon virus as a species in the genus Arenavirus • Designate Allpahuayo virus as a species in the genus Arenavirus Family Birnaviridae • Assign Blotched snakehead virus as an unassigned species in family Birnaviridae Family Circoviridae • Create a new genus (Anellovirus) with Torque teno virus as type species Family Coronaviridae • Recognize a new species Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus in the genus Coro- navirus, family Coronaviridae, order Nidovirales -

The Genome of Nanoarchaeum Equitans: Insights Into Early Archaeal Evolution and Derived Parasitism

The genome of Nanoarchaeum equitans: Insights into early archaeal evolution and derived parasitism Elizabeth Waters†‡, Michael J. Hohn§, Ivan Ahel¶, David E. Graham††, Mark D. Adams‡‡, Mary Barnstead‡‡, Karen Y. Beeson‡‡, Lisa Bibbs†, Randall Bolanos‡‡, Martin Keller†, Keith Kretz†, Xiaoying Lin‡‡, Eric Mathur†, Jingwei Ni‡‡, Mircea Podar†, Toby Richardson†, Granger G. Sutton‡‡, Melvin Simon†, Dieter So¨ ll¶§§¶¶, Karl O. Stetter†§¶¶, Jay M. Short†, and Michiel Noordewier†¶¶ †Diversa Corporation, 4955 Directors Place, San Diego, CA 92121; ‡Department of Biology, San Diego State University, 5500 Campanile Drive, San Diego, CA 92182; §Lehrstuhl fu¨r Mikrobiologie und Archaeenzentrum, Universita¨t Regensburg, Universita¨tsstrasse 31, D-93053 Regensburg, Germany; ‡‡Celera Genomics Rockville, 45 West Gude Drive, Rockville, MD 20850; Departments of ¶Molecular Biophysics and Biochemistry and §§Chemistry, Yale University, New Haven, CT 06520-8114; and ʈDepartment of Biochemistry, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, Blacksburg, VA 24061 Communicated by Carl R. Woese, University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign, Urbana, IL, August 21, 2003 (received for review July 22, 2003) The hyperthermophile Nanoarchaeum equitans is an obligate sym- (6–8). Genomic DNA was either digested with restriction en- biont growing in coculture with the crenarchaeon Ignicoccus. zymes or sheared to provide clonable fragments. Two plasmid Ribosomal protein and rRNA-based phylogenies place its branching libraries were made by subcloning randomly sheared fragments point early in the archaeal lineage, representing the new archaeal of this DNA into a high-copy number vector (Ϸ2.8 kbp library) kingdom Nanoarchaeota. The N. equitans genome (490,885 base or low-copy number vector (Ϸ6.3 kbp library). DNA sequence pairs) encodes the machinery for information processing and was obtained from both ends of plasmid inserts to create repair, but lacks genes for lipid, cofactor, amino acid, or nucleotide ‘‘mate-pairs,’’ pairs of reads from single clones that should be biosyntheses. -

A Persistent Giant Algal Virus, with a Unique Morphology, Encodes An

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.07.30.228163; this version posted January 13, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. 1 A persistent giant algal virus, with a unique morphology, encodes an 2 unprecedented number of genes involved in energy metabolism 3 4 Romain Blanc-Mathieu1,2, Håkon Dahle3, Antje Hofgaard4, David Brandt5, Hiroki 5 Ban1, Jörn Kalinowski5, Hiroyuki Ogata1 and Ruth-Anne Sandaa6* 6 7 1: Institute for Chemical Research, Kyoto University, Gokasho, Uji, 611-0011, Japan 8 2: Laboratoire de Physiologie Cellulaire & Végétale, CEA, Univ. Grenoble Alpes, 9 CNRS, INRA, IRIG, Grenoble, France 10 3: Department of Biological Sciences and K.G. Jebsen Center for Deep Sea Research, 11 University of Bergen, Bergen, Norway 12 4: Department of Biosciences, University of Oslo, Norway 13 5: Center for Biotechnology, Universität Bielefeld, Bielefeld, 33615, Germany 14 6: Department of Biological Sciences, University of Bergen, Bergen, Norway 15 *Corresponding author: Ruth-Anne Sandaa, +47 55584646, [email protected] 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.07.30.228163; this version posted January 13, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. 16 Abstract 17 Viruses have long been viewed as entities possessing extremely limited metabolic 18 capacities. -

The Mínimum Cell

The minimum cell GENOMIC – ADVANCED GENETICS AUTHOR: I. ODEI BARREÑADA Overview The Concept Small genomes Minimal gene set Approache theories Minimal genome proyect Future insight The concept “MINIMUN CELL“ The smallest size (of genetic The smallest unit of life that can information) replicate autonomously = minimum genome Small genomes Circovirus (1.800 base pairs / 3 gens) Virus Carsonella ruddi (159 kb /182 genes) Symbiont Nanoarchaeum equitans (490 kb/ 553 genes) Parasite Mycoplasma genitalium (582 kb/ 521 genes ) Parasite Pelagibacter ubique (1,3 Mb/ 1,370 genes) Free-living Smallest genomes Circovirus (1.800 base pairs / 3 gens) Virus Carsonella ruddi (159 kb /182 genes) Symbiont Nanoarchaeum equitans (490 kb/ 553 genes) Parasite Mycoplasma genitalium (582 kb/ 521 genes ) Parasite Pelagibacter ubique (1,3 Mb/ 1,370 genes) Free-living (Giovannoni et al., 2005) “MINIMAL GENE SET” By genome comparison Ubiquitous genes: Translation Transcription Replication of DNA Variable genes: Depends of environment (Koonin, 2003) Theories for reach the minimum cell Two approaches Top – Down knock-down known organism Bottom-up --> build from synthetics DNA Minimal genome project J. Craig Venter Institute Search of essential genes Gene disruption by transposons Seq the survivors organisms Detect the disrupted gene Declare this genes as NON-ESENTIAL In M. genitalium only 382 of 521 genes are essential (Gibson et al., 2011) Build de novo M. genitalium genome Future insight - Cell design Create artificial cells for: Generation of hydrogen for fuel Capturing excess carbon dioxide in the atmosphere Drug delivery directly into the body As Enzyme therapy Artificial blood cells … And all you can think References Koonin E V. -

The Mysterious Orphans of Mycoplasmataceae

The mysterious orphans of Mycoplasmataceae Tatiana V. Tatarinova1,2*, Inna Lysnyansky3, Yuri V. Nikolsky4,5,6, and Alexander Bolshoy7* 1 Children’s Hospital Los Angeles, Keck School of Medicine, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, 90027, California, USA 2 Spatial Science Institute, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, 90089, California, USA 3 Mycoplasma Unit, Division of Avian and Aquatic Diseases, Kimron Veterinary Institute, POB 12, Beit Dagan, 50250, Israel 4 School of Systems Biology, George Mason University, 10900 University Blvd, MSN 5B3, Manassas, VA 20110, USA 5 Biomedical Cluster, Skolkovo Foundation, 4 Lugovaya str., Skolkovo Innovation Centre, Mozhajskij region, Moscow, 143026, Russian Federation 6 Vavilov Institute of General Genetics, Moscow, Russian Federation 7 Department of Evolutionary and Environmental Biology and Institute of Evolution, University of Haifa, Israel 1,2 [email protected] 3 [email protected] 4-6 [email protected] 7 [email protected] 1 Abstract Background: The length of a protein sequence is largely determined by its function, i.e. each functional group is associated with an optimal size. However, comparative genomics revealed that proteins’ length may be affected by additional factors. In 2002 it was shown that in bacterium Escherichia coli and the archaeon Archaeoglobus fulgidus, protein sequences with no homologs are, on average, shorter than those with homologs [1]. Most experts now agree that the length distributions are distinctly different between protein sequences with and without homologs in bacterial and archaeal genomes. In this study, we examine this postulate by a comprehensive analysis of all annotated prokaryotic genomes and focusing on certain exceptions. -

Insights Into Archaeal Evolution and Symbiosis from the Genomes of a Nanoarchaeon and Its Inferred Crenarchaeal Host from Obsidian Pool, Yellowstone National Park

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Microbiology Publications and Other Works Microbiology 4-22-2013 Insights into archaeal evolution and symbiosis from the genomes of a nanoarchaeon and its inferred crenarchaeal host from Obsidian Pool, Yellowstone National Park Mircea Podar University of Tennessee - Knoxville, [email protected] Kira S. Makarova National Institutes of Health David E. Graham University of Tennessee - Knoxville, [email protected] Yuri I. Wolf National Institutes of Health Eugene V. Koonin National Institutes of Health See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_micrpubs Part of the Microbiology Commons Recommended Citation Biology Direct 2013, 8:9 doi:10.1186/1745-6150-8-9 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Microbiology at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Microbiology Publications and Other Works by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Authors Mircea Podar, Kira S. Makarova, David E. Graham, Yuri I. Wolf, Eugene V. Koonin, and Anna-Louise Reysenbach This article is available at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange: https://trace.tennessee.edu/ utk_micrpubs/44 Podar et al. Biology Direct 2013, 8:9 http://www.biology-direct.com/content/8/1/9 RESEARCH Open Access Insights into archaeal evolution and symbiosis from the genomes of a nanoarchaeon and its inferred crenarchaeal host from Obsidian Pool, Yellowstone National Park Mircea Podar1,2*, Kira S Makarova3, David E Graham1,2, Yuri I Wolf3, Eugene V Koonin3 and Anna-Louise Reysenbach4 Abstract Background: A single cultured marine organism, Nanoarchaeum equitans, represents the Nanoarchaeota branch of symbiotic Archaea, with a highly reduced genome and unusual features such as multiple split genes. -

Keizo Nagasaki and Gunnar Bratbak. Isolation of Viruses Infecting

MANUAL of MAVE Chapter 10, 2010, 92–101 AQUATIC VIRAL ECOLOGY © 2010, by the American Society of Limnology and Oceanography, Inc. Isolation of viruses infecting photosynthetic and nonphotosynthetic protists Keizo Nagasaki1* and Gunnar Bratbak2† 1National Research Institute of Fisheries and Environment of Inland Sea, Fisheries Research Agency, 2-17-5 Maruishi, Hatsukaichi, Hiroshima 739-0452, Japan 2University of Bergen, Department of Biology, Box 7800, N-5020 Bergen, Norway Abstract Viruses are the most abundant biological entities in aquatic environments and our understanding of their eco- logical significance has increased tremendously since the first discovery of their high abundance in natural waters. About 40 viruses infecting eukaryotic algae and 4 viruses infecting nonphotosynthetic protists have so far been isolated and characterized to different extents. The isolated viruses infecting phytoplankton (Chlorophyceae, Prasinophyceae, Haptophyceae, Dinophyceae, Pelagophyceae, Raphidophyceae, and Bacillariophyceae) and heterotrophic protists (Bicosoecophyceae, Acanthamoebidae, and Thraustochytriaceae) are all lytic. Some of the brown algal phaeoviruses, which infect host spores or gametes, have also been found in a latent form (lysogeny) in vegetative cells. Viruses infecting eukaryotic photosynthetic and nonphotosynthetic protists are highly diverse both in size (ca. 20–220 nm in diameter), genome type (double-strand deoxyribonu- cleic acid [dsDNA], single-strand [ss]DNA, ds–ribonucleic acid [dsRNA], ssRNA), and genome size [4.4–560 kb]). Availability of host–virus laboratory cultures is a necessary prerequisite for characterization of the viruses and for investigation of host–virus interactions. In this report we summarize and comment on the techniques used for preparation of host cultures and for screening, cloning, culturing, and maintaining viruses in the laboratory. -

<I>AUREOCOCCUS ANOPHAGEFFERENS</I>

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 12-2016 MOLECULAR AND ECOLOGICAL ASPECTS OF THE INTERACTIONS BETWEEN AUREOCOCCUS ANOPHAGEFFERENS AND ITS GIANT VIRUS Mohammad Moniruzzaman University of Tennessee, Knoxville, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Part of the Environmental Microbiology and Microbial Ecology Commons Recommended Citation Moniruzzaman, Mohammad, "MOLECULAR AND ECOLOGICAL ASPECTS OF THE INTERACTIONS BETWEEN AUREOCOCCUS ANOPHAGEFFERENS AND ITS GIANT VIRUS. " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2016. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/4152 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Mohammad Moniruzzaman entitled "MOLECULAR AND ECOLOGICAL ASPECTS OF THE INTERACTIONS BETWEEN AUREOCOCCUS ANOPHAGEFFERENS AND ITS GIANT VIRUS." I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in Microbiology. Steven W. Wilhelm, Major Professor We have read this dissertation -

Proteome Science Biomed Central

Proteome Science BioMed Central Research Open Access Proteomic analysis of the EhV-86 virion Michael J Allen*1, Julie A Howard2, Kathryn S Lilley2 and William H Wilson1,3 Address: 1Plymouth Marine Laboratory, Prospect Place, The Hoe, Plymouth, PL1 3DH, UK, 2Cambridge Centre for Proteomics, Department of Biochemistry, University of Cambridge, Tennis Court Road, Cambridge, CB2 1QR, UK and 3Bigelow Laboratory for Ocean Sciences, 180 McKown Point, PO Box 475, W. Boothbay Harbor, Maine, 04575-0475, USA Email: Michael J Allen* - [email protected]; Julie A Howard - [email protected]; Kathryn S Lilley - [email protected]; William H Wilson - [email protected] * Corresponding author Published: 17 March 2008 Received: 23 January 2008 Accepted: 17 March 2008 Proteome Science 2008, 6:11 doi:10.1186/1477-5956-6-11 This article is available from: http://www.proteomesci.com/content/6/1/11 © 2008 Allen et al; licensee BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Abstract Background: Emiliania huxleyi virus 86 (EhV-86) is the type species of the genus Coccolithovirus within the family Phycodnaviridae. The fully sequenced 407,339 bp genome is predicted to encode 473 protein coding sequences (CDSs) and is the largest Phycodnaviridae sequenced to date. The majority of EhV-86 CDSs exhibit no similarity to proteins in the public databases. Results: Proteomic analysis by 1-DE and then LC-MS/MS determined that the virion of EhV-86 is composed of at least 28 proteins, 23 of which are predicted to be membrane proteins. -

Title Analysis of the Genome Architecture of The

Analysis of the genome architecture of the hyperthermopholic Title archaeon Thermococcus kodakarensis( Dissertation_全文 ) Author(s) Maruyama, Hugo Citation 京都大学 Issue Date 2011-03-23 URL https://doi.org/10.14989/doctor.k16233 Right Type Thesis or Dissertation Textversion author Kyoto University Analysis of the genome architecture of the hyperthermophilic archaeon Thermococcus kodakarensis Hugo Maruyama 要旨 ゲノム DNA は細胞内で高度に折りたたまれ、この染色体高次構造は転写・複製・染色体分 配といった機構と密接に結びついている。染色体の主要な構成タンパク質は真核生物では ヒストン、バクテリアでは HU と全く異なるが、一様な基本構造を基にゲノム DNA が階層 的に折りたたまれている点で両者の染色体構造は共通している。アーキアは真核生物・バ クテリアと並ぶ生命の第三のドメインであり、遺伝情報の発現(複製・転写・翻訳)の機 構は真核生物に、代謝経路はバクテリアに近い。アーキアには染色体を構成するタンパク 質として真核生物のヒストンに相同なもの、バクテリアの HU に相同なもの、アーキア特有 の Alba と呼ばれるタンパク質などが存在し、種によってゲノムがコードするタンパク質の 組合せが異なる。様々なアーキアのゲノムがどのような高次構造を形成しているかを明ら かにすることで、三つのドメインにわたるゲノム構造の共通性あるいは多様性を明らかに できる。本研究ではその第一歩としてヒストンを持つ超好熱性アーキア Thermococcus kodakarensis の染色体構造を解析した。 T. kodakarensis の染色体に含まれるタンパク質を質量分析により同定した結果、ヒ ストン、Alba、TK0471(TrmBL2)、 RNA ポリメラーゼ等の DNA 結合タンパク質が含まれ ることが分かった。TK0471 は転写因子 TrmB と相同な機能未知の DNA 結合タンパク質で あった。次に、染色体をミクロコッカルヌクレアーゼで部分消化した後、5%-20%のショ糖 密度勾配遠心により構成タンパク質の異なる染色体断片が分離された。原子間力顕微鏡に よる解析から、ヒストンは DNA 上に beads-on-a-string 構造を、TK0471 は線維状の構造を形 成することが示された。また大腸菌で発現させた組換えタンパク質(ヒストンおよび TK0471)を用いて同様の構造が DNA 上に再構成された。ショ糖密度勾配で分離されたそ れぞれの染色体断片に含まれる DNA 配列を超並列シークエンサーで同定した結果、ヒスト ンおよび TK0471 はゲノム上のプロモーター領域にもコーディング領域にも偏りなく存在 するが、両者の存在する領域は重複しない傾向があった。以上の結果から、T. kodakarensis の染色体上には、構成タンパク質および構造の異なる領域が存在することが明らかとなっ た。相同組換えにより TK0471 遺伝子を破壊すると染色体の DNA 消化酵素に対する感受性 が高まった。また、約 100 個の遺伝子の転写産物量が増加した。TK0471 破壊株における各 -

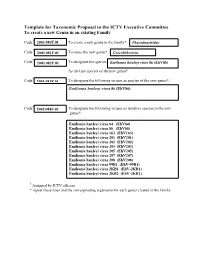

Template for Taxonomic Proposal to the ICTV Executive Committee to Create a New Genus in an Existing Family

Template for Taxonomic Proposal to the ICTV Executive Committee To create a new Genus in an existing Family † Code 2003.080F.01 To create a new genus in the family* Phycodnaviridae † Code 2003.081F.01 To name the new genus* Coccolithovirus † Code 2003.082F.01 To designate the species Emiliania huxleyi virus 86 (EhV86) As the type species of the new genus* † Code 2003.083F.01 To designate the following viruses as species of the new genus*: Emiliania huxleyi virus 86 (EhV86) † Code 2003.084F.01 To designate the following viruses as tentative species in the new genus*: Emiliania huxleyi virus 84 (EhV84) Emiliania huxleyi virus 88 (EhV88) Emiliania huxleyi virus 163 (EhV163) Emiliania huxleyi virus 201 (EhV201) Emiliania huxleyi virus 202 (EhV202) Emiliania huxleyi virus 203 (EhV203) Emiliania huxleyi virus 205 (EhV205) Emiliania huxleyi virus 207 (EhV207) Emiliania huxleyi virus 208 (EhV208) Emiliania huxleyi virus 99B1 (EhV-99B1) Emiliania huxleyi virus 2KB1 (EhV-2KB1) Emiliania huxleyi virus 2KB2 (EhV-2KB2) † Assigned by ICTV officers * repeat these lines and the corresponding arguments for each genus created in the family Author(s) with email address(es) of the Taxonomic Proposal Dr Willie Wilson [email protected] Dr Declan Schroeder [email protected] New Taxonomic Order Order Caudovirales Family Phycodnaviridae Genus Coccolithovirus Type Species Emiliania huxleyi virus 86 (EhV86) List of Species in the genus Emiliania huxleyi virus 86 (EhV86) ............ List of Tentative Species in the Genus Emiliania huxleyi virus 84 (EhV84) Emiliania huxleyi -

Evidence to Support Safe Return to Clinical Practice by Oral Health Professionals in Canada During the COVID-19 Pandemic: a Repo

Evidence to support safe return to clinical practice by oral health professionals in Canada during the COVID-19 pandemic: A report prepared for the Office of the Chief Dental Officer of Canada. November 2020 update This evidence synthesis was prepared for the Office of the Chief Dental Officer, based on a comprehensive review under contract by the following: Paul Allison, Faculty of Dentistry, McGill University Raphael Freitas de Souza, Faculty of Dentistry, McGill University Lilian Aboud, Faculty of Dentistry, McGill University Martin Morris, Library, McGill University November 30th, 2020 1 Contents Page Introduction 3 Project goal and specific objectives 3 Methods used to identify and include relevant literature 4 Report structure 5 Summary of update report 5 Report results a) Which patients are at greater risk of the consequences of COVID-19 and so 7 consideration should be given to delaying elective in-person oral health care? b) What are the signs and symptoms of COVID-19 that oral health professionals 9 should screen for prior to providing in-person health care? c) What evidence exists to support patient scheduling, waiting and other non- treatment management measures for in-person oral health care? 10 d) What evidence exists to support the use of various forms of personal protective equipment (PPE) while providing in-person oral health care? 13 e) What evidence exists to support the decontamination and re-use of PPE? 15 f) What evidence exists concerning the provision of aerosol-generating 16 procedures (AGP) as part of in-person