Christology in Film and Musical Drama

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

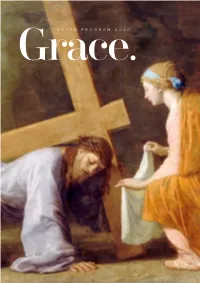

L E N T E N P R O G R a M 2 0

LENTEN PROGRAM 2020 Grace. 12 TheFIRST Temptation. SUNDAY OF LENT CONTENTS 22 The SECONDTransfiguration. SUNDAY OF LENT 4 Leading the weekly sessions 5 Contributor biographies Sunday reflections 32 Fr Christopher G Sarkis The Samaritan Sr Anastasia Reeves OP THIRD SUNDAYwoman. OF LENT Mgr Graham Schmitzer 6 Contributor biographies Weekday reflections 42 Sr Susanna Edmunds OP Healing the Fr Damian Ference blind man. Peter Gilmore FOURTH SUNDAY OF LENT Michael “Gomer” Gormley Sr Mary Helen Hill OP Fr Antony Jukes OFM Sr Elena Marie Piteo OP 53 Sr Magdalen Mather OSB Darren McDowell RaisingFIFTH SUNDAY Lazarus. OF LENT Trish McCarthy Matthew Ockinga Fr Chris Pietraszko Mother Hilda Scott OSB 62 Professor Eleonore Stump Michelle Vass ThePALM Passion. SUNDAY 74 HeEASTER is risen. SUNDAY 3 The Temptation.FIRST SUNDAY OF LENT 4 ARTWORK REFLECTION He was born of a poor family, and his mother had hoped he would become a priest. He was involved in the insurrection of 1848 which erupted in Naples. After his death, he was labelled as one of the warrior artists of Italy. Is this reflected in the painting we are contemplating—a battle? The landscape is desert, not a slice of green to be seen. Christ seems to be in a completely relaxed mode, an attitude of prayer, engrossed in conversation with his Father. Fasting has not emaciated him. He seems completely in control. The Temptation of Christ But, on the left is the Tempter. In Latin, “left” is Domenico Morelli (1823–1901) sinistra, from which we get our word “sinister”. It “The Temptation of Christ”, c. -

Spe Salvi: Assessing the Aerodynamic Soundness of Our Civilizational Flying Machine

Journal of Religion and Business Ethics Volume 1 Article 3 January 2010 Spe Salvi: Assessing the Aerodynamic Soundness of Our Civilizational Flying Machine Jim Wishloff University of Lethbridge, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/jrbe Recommended Citation Wishloff, Jim (2010) "Spe Salvi: Assessing the Aerodynamic Soundness of Our Civilizational Flying Machine," Journal of Religion and Business Ethics: Vol. 1 , Article 3. Available at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/jrbe/vol1/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the LAS Proceedings, Projects and Publications at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Religion and Business Ethics by an authorized editor of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Wishloff: Spe Salvi INTRODUCTION In his very popular book Ishmael, author Daniel Quinn questions the sustainability of our civilization in a thought-provoking way. Quinn does this by asking the reader to consider the early attempts to achieve powered flight, and, more specifically, to imagine someone jumping off in “one of those wonderful pedal-driven contraptions with flapping wings.”1 At first, all seems well for the would-be flyer but, of course, in time he crashes. This is his inevitable fate since the laws of aerodynamics have not been observed. Quinn uses this picture to get us to assess whether or not we have built “a civilization that flies.”2 The symptoms of environmental distress are evident, so much so that U.N. Secretary General Ban Ki-Moon puts us on a path to “oblivion.”3 Add to this the economic and cultural instability in the world and it is hard not to acknowledge that the ground is rushing up at us. -

Second Chances Holy Spirit Touch My Lips, Open Our Hearts, And

Sermon for Date Church of the Holy Comforter Joseph Klenzmann Second Chances Holy Spirit Touch My Lips, Open Our Hearts, And Transform Our Lives. Amen Well it is a new season, a new year in the life of the church. Advent, a season that is worshiped in a more solemn, quiet, less festive manor than other seasons in the church. There is no joyous Christmas music during the four weeks of advent. Advent is a time where Christians around the world commemorate the first coming of the messiah and our ardent anticipation of Christ’s second coming as Judge. Actually, the word Advent comes from the Latin word adventus which means “coming” or “Arrival”. Advent is a time to prepare for his coming. A time to look at our lives, a second chance to be the kind of person the lord knows we can be. The bible stories of John the Baptist are stories of preparation and transition. John has come to “Make Straight The Path”. To quote one of my favorite songs from the play Godspell “Prepare Ye The Way Of The Lord”. That is actually Mark chapter 1 verse 3, but I really liked Godspell. John the Baptist is a transition from the PROMISE of the Old Testament to the New Testament REALITY of Christ in the flesh. In Advent each year, we remember that reality and the new promise of his second coming. In Jeremiah, we heard God tell Jeremiah: “I Will Fulfill The Promise I Made To The House Of Israel And The House Of Judah” we also heard that god will have “A Righteous Branch Spring Up From David” This is the Messianic message told throughout the Old Testament, told by the Patriarchs and the Profits. -

Continuity and Tradition: the Prominent Role of Cyrillian Christology In

Jacopo Gnisci Jacopo Gnisci CONTINUITY AND TRADITION: THE PROMINENT ROLE OF CYRILLIAN CHRISTOLOGY IN FIFTEENTH AND SIXTEENTH CENTURY ETHIOPIA The Ethiopian Tewahedo Church is one of the oldest in the world. Its clergy maintains that Christianity arrived in the country during the first century AD (Yesehaq 1997: 13), as a result of the conversion of the Ethiopian Eunuch, narrated in the Acts of the Apostles (8:26-39). For most scholars, however, the history of Christianity in the region begins with the conversion of the Aksumite ruler Ezana, approximately during the first half of the fourth century AD.1 For historical and geographical reasons, throughout most of its long history the Ethiopian Church has shared strong ties with Egypt and, in particular, with the Coptic Orthodox Church of Alexandria. For instance, a conspicuous part of its literary corpus, both canonical and apocryphal, is drawn from Coptic sources (Cerulli 1961 67:70). Its liturgy and theology were also profoundly affected by the developments that took place in Alexandria (Mercer 1970).2 Furthermore, the writings of one of the most influential Alexandrian theologians, Cyril of Alexandria (c. 378-444), played a particularly significant role in shaping Ethiopian theology .3 The purpose of this paper is to highlight the enduring importance and influence of Cyril's thought on certain aspects of Ethiopian Christology from the early developments of Christianity in the country to the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. Its aim, therefore, is not to offer a detailed examination of Cyril’s work, or more generally of Ethiopian Christology. Rather, its purpose is to emphasize a substantial continuity in the traditional understanding of the nature of Christ amongst Christian 1 For a more detailed introduction to the history of Ethiopian Christianity, see Kaplan (1982); Munro-Hay (2003). -

The Temptation of Christ

The Temptation of Christ REDEMPTION SERIES # 2 Ellen G. White 1877 Contents Confrontation in the Desert Adam and Eve and their Eden home The Test of Probation Paradise Lost. Plan of Redemption Sacrificial Offerings Appetite and Passion A Threat to Satan's Kingdom The Temptation Christ as a Second Adam Terrible Effects of Sin upon Man The First Temptation of Christ Significance of the Test Christ did no Miracle for Himself He Parleyed not with Temptation Victory through Christ The Second Temptation The Sin of Presumption Christ our Hope and Example The Third Temptation Christ's Temptation Ended Christian Temperance. Self-indulgence in Religion's Garb More Than One Fall. Health and Happiness. Strange Fire. Presumptuous Rashness and Intelligent Faith. Spiritism Character Development Confrontation in the Desert After the baptism of Jesus in Jordan He was led by the Spirit into the wilderness, to be tempted of the devil. When He had come up out of the water, He bowed upon Jordan's banks and pleaded with the great Eternal for strength to endure the conflict with the fallen foe. The opening of the heavens and the descent of the excellent glory attested His divine character. The voice from the Father declared the close relation of Christ to His Infinite Majesty: "This is my beloved Son, in whom I am well pleased." The mission of Christ was soon to begin. But He must first withdraw from the busy scenes of life to a desolate wilderness for the express purpose of bearing the threefold test of temptation in behalf of those He had come to redeem. -

On the Temptation of Jesus

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 1-1-1993 On the temptation of Jesus. Thomas P. Sullivan University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1 Recommended Citation Sullivan, Thomas P., "On the temptation of Jesus." (1993). Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014. 2212. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1/2212 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ON THE TEMPTATION OF JESUS A Dissertation Presented by THOMAS P. SULLIVAN Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY September 1993 Department of Philosophy Copyright by Thomas P. Sullivan 1993 All Rights Reserved ON THE TEMPTATION OF JESUS A Dissertation Presented by THOMAS P. SULLIVAN Approved as to style and content by: Gareth B. Matthews, Chair Fred Feldman, Member To Fred, Lois, and Elizabeth In Memory of Lindsay ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank a number of people who have helped to see me through my graduate work in general and through this dissertation in particular. Before anyone else, I should mention my grandmothers, Elizabeth Stout and Laura Sullivan. Neither of them lived long enough to see me complete my Ph.D., but each of them always supported my academic career actively and enthusiastically. My parents, Ginny and Neal, have continued that support as long as I can remember, and they have consistently encouraged me to work hard (and to finish!). -

First Theology Requirement

FIRST THEOLOGY REQUIREMENT THEO 10001, 20001 FOUNDATIONS OF THEOLOGY: BIBLICAL/HISTORICAL **GENERAL DESCRIPTION** This course, prerequisite to all other courses in Theology, offers a critical study of the Bible and the early Catholic traditions. Following an introduction to the Old and New Testament, students follow major post biblical developments in Christian life and worship (e.g. liturgy, theology, doctrine, asceticism), emphasizing the first five centuries. Several short papers, reading assignments and a final examination are required. THEO 20001/01 FOUNDATIONS OF THEOLOGY/BIBLICAL/HISTORICAL GIFFORD GROBIEN 11:00-12:15 TR THEO 20001/02 FOUNDATIONS OF THEOLOGY/BIBLICAL/HISTORICAL 12:30-1:45 TR THEO 20001/03 FOUNDATIONS OF THEOLOGY/BIBLICAL/HISTORICAL 1:55-2:45 MWF THEO 20001/04 FOUNDATIONS OF THEOLOGY/BIBLICAL/HISTORICAL 9:35-10:25 MWF THEO 20001/05 FOUNDATIONS OF THEOLOGY/BIBLICAL/HISTORICAL 4:30-5:45 MW THEO 20001/06 FOUNDATIONS OF THEOLOGY/BIBLICAL/HISTORICAL 3:00-4:15 MW 1 SECOND THEOLOGY REQUIREMENT Prerequisite Three 3 credits of Theology (10001, 13183, 20001, or 20002) THEO 20103 ONE JESUS & HIS MANY PORTRAITS 9:30-10:45 TR JOHN MEIER XLIST CST 20103 This course explores the many different faith-portraits of Jesus painted by the various books of the New Testament, in other words, the many ways in which and the many emphases with which the story of Jesus is told by different New Testament authors. The class lectures will focus on the formulas of faith composed prior to Paul (A.D. 30-50), the story of Jesus underlying Paul's epistles (A.D. -

Jesus of Nazareth—Film Errors

JESUS OF NAZARETH—FILM ERRORS by Avram Yehoshua The SeedofAbraham.net Some Errors or Things Not Accurate 1. The rabbi of Nazareth, as well as many other men in the movie, would not have worn a white (or any other colored) knitted cap on his head. The knitted cap was not known in the days of Yeshua, but only many centuries later. The kipa or yarmulka is not biblical, but pagan.1 2. Many of the men in the film (e.g. the man in the red cloak at the betrothal of Joseph and Mary) had a beard, but didn’t have a mustache. This form of shaving, where one has a beard, but no mustache, only came into existence in the 1700s through the Amish and Mennonites because they didn’t want to be mistaken for Jews. All male Torah observant Jews2 are required to wear full, untrimmed beards, which obviously, would include a mustache (Lev. 19:27).3 1. Yeshua, as well as all the Jewish Apostles and Jewish men of that time would have had full, untrimmed beards (Lev. 19:27; Is. 50:6; Mic. 5:1), not a short, trimmed beard as the movie por- trays Him and many other Jews. 3. The men in the synagogue with a tallit on (Jewish prayer shawl) is also a mistake. This would not have been known in the days of Yeshua because the tallit of Yeshua’s day was actually their outer garment of clothing, with the tzit’ziot (tassels) in the garment toward the bottom sides, and hence, no need to have a rectangular piece of material to drape over one’s shoulders or head. -

An Interpretation of the English Bible

AN INTERPRETATION OF THE ENGLISH BIBLE BY B. H. CARROLL Late President of Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary, Fort Worth, Texas Edited by J. B. Cranfill BAKER BOOK HOUSE Grand Rapids, Michigan New and complete edition Copyright 1948, Broadman Press Reprinted by Baker Book House with permission of Broadman Press ISBN: 0-8010-2344-0 VOLUME 10 THE FOUR GOSPELS CONTENTS I Introduction – The Four Gospels II Introduction – The Fifth Gospel III Introduction – The Several Historians IV Luke's Dedication and John's Prologue (Luke 1:1-4; John 1:1-18) V Beginnings of Matthew and Luke (Matthew 1:1-17; Luke 1:5-80; 3:23-38) VI Beginnings of Matthew and Luke (Continued) VII Beginnings of Matthew and Luke (Continued) (Matthew 1:18-25; Luke 2:1-20) VIII Beginnings of Matthew and Luke (Continued) (Luke 2:21- 38; Matthew 2:1-12) IX Beginnings of Matthew and Luke (Concluded) (Matthew 2:13-28; Luke 2:39-52) X John the Baptist XI The Kingdom of our Lord Jesus Christ (Matthew 3:1-12; Mark 1:1-8; Luke 3:l-18) XII The Beginning of the Ministry of John the Baptist (Matthew 3:l-12; Mark 1:1-8; Luke 3:1-18) XIII The Nature, Necessity, Importance and Definition of Repentance XIV The Object of Repentance XV Motives and Encouragements to Repentance XVI Motives and Encouragements to Repentance (Continued) XVII Motives and Encouragements to Repentance (Conclusion) XVIII The Ministry of Jon the Baptist (Continued) (Matthew 3:11- 17; Mark 1:1-11; Luke 3:15-23) XIX The Culmination of John’s Ministry XX The Temptation of Christ (Matthew 4:1-11; Mark 1:12-13; Luke -

![This Jesus Must Die ]Esus Christ Superstar Moderato Annas Good Cai- A- Phas The Coun- Cil Waits for You](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5365/this-jesus-must-die-esus-christ-superstar-moderato-annas-good-cai-a-phas-the-coun-cil-waits-for-you-325365.webp)

This Jesus Must Die ]Esus Christ Superstar Moderato Annas Good Cai- A- Phas The Coun- Cil Waits for You

This Jesus Must Die ]esus Christ Superstar Moderato Annas Good Cai- a- phas the coun- cil waits for you. Tbe Pha- ri- Moderato f 4 sees and Priests are here for you. Caiaphas Ah gent tle 2 6 men you why we arehere.We'venot much time and quite a pro-blem here. Mob (outside )Boys Ho Mob (Outside) Girls 10 Ho sannaSu per star ho san nasup per star san-naSu-per-star,Ho- san.na Su-per-star,Ho- san-na Su-per-star,Ho- san- na Su-per- star cresc poco a poco 3 14 Annas listen tothat howl-ingmobofblock-headsinthe street! A [guide part poco ad lib ] Fm7 Bb7 Fm7 Bb7 16 Annas and Preist2 trickortwowith le-persandthewholetown'son it'sfeet. Heis dan ger Preist1 Caiaphas & Priest 3 He is dan ger Fm7 Bb7 Fm7 Bb7 Bb E Bb 4 19 Preist 3 ous He is dan ger ous that ous He is dan ger ous Mob (outside) Je-susChrist Su-per-star TeIl that you're who they Je-susChrist Su-per-star TeIl that you're who they B -

THE NEW REALITY: the BEATITUDES Water from Rock, January 17, 2017, Tim Smith

THE NEW REALITY: THE BEATITUDES Water From Rock, January 17, 2017, Tim Smith CONTEXT FOR THE BEATITUDES Matthew 4:17-22 17From that time Jesus began to proclaim, ‘Repent, for the kingdom of heaven has come near.’ 18 As he walked by the Sea of Galilee, he saw two brothers, Simon, who is called Peter, and Andrew his brother, casting a net into the lake—for they were fishermen. 19And he said to them, ‘Follow me, and I will make you fish for people.’ 20Immediately they left their nets and followed him. 21As he went from there, he saw two other brothers, James son of Zebedee and his brother John, in the boat with their father Zebedee, mending their nets, and he called them. 22Immediately they left the boat and their father, and followed him. THE BEATITUDES Matthew 5:1-12 When Jesus saw the crowds, he went up the mountain; and after he sat down, his disciples came to him. 2Then he began to speak, and taught them, saying: 3 ‘Blessed are the poor in spirit, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven. 4 ‘Blessed are those who mourn, for they will be comforted. 5 ‘Blessed are the meek, for they will inherit the earth. 6 ‘Blessed are those who hunger and thirst for righteousness, for they will be filled. 7 ‘Blessed are the merciful, for they will receive mercy. 8 ‘Blessed are the pure in heart, for they will see God. 9 ‘Blessed are the peacemakers, for they will be called children of God. 10 ‘Blessed are those who are persecuted for righteousness’ sake, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven. -

Elevating Voices Across Stage and Screen

Elevating voices across stage and screen clients include beginners, aspiring singers Based in London, Fiona continued to coach and performing arts students as well as singers and, in 2010, started working for top-tier professionals. Passionate about Andrew Lloyd Webber and his production vocal health and technique, Fiona believes company, the Really Useful Group. She that anyone can sing and tailors each worked on her first major international lesson to the client’s needs. She works production in 2012, as the vocal coach on remotely via Skype and in person from her Lloyd Webber’s Jesus Christ Superstar, studio at the London Palladium. and has since worked on dozens of major shows across television, film and theatre Fiona grew up on a farm outside around the world. Edinburgh where she immersed herself in music from a young age, initially training Fiona is always at the leading edge of in dance. In 2006, she left Scotland to vocal education. She travels globally to FIONA study Music at the Paul McCartney conferences that are advancing the field Liverpool Institute for Performing Arts, of vocal science and is supported by MCDOUGAL where her vocal coach inspired her to a network of exceptional ENT doctors, study voice education alongside her speech and language therapists, and degree. When she graduated with a first physiotherapists. She is considered a Fiona has worked with some of the biggest class honours degree in 2010, she already valuable link between singers and industry names in the entertainment industry, from had three years of coaching experience. representatives and consults for record Glenn Close to Taylor Swift, Judi Dench to She was the lead singer in a pop duo labels, agents, managers, performing Jennifer Hudson – but her busy studio also called Untouched (along with songwriting arts colleges, choreographers, directors, embraces people who sing for pleasure partner David Wilson), which later signed songwriters, film studios, musicians and and want to improve their voice.