FINAL REPORT Children in Moldova Are Cared for in Safe and Secure Families Project

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Report on Research Into the Process of Transition from Kindergarten to School

Ensuring Educational Inclusion for Children with Special Educational Needs Report on Research into the Process of Transition from Kindergarten to School Chisinau, 2015 1 Contents Abbreviations and acronymns ................................ ................................ .................... 2 1. Introduction ................................ ................................ ................................ .......... 3 1.1. Background to the research ................................ ................................ ............. 3 1.2. Background to the context ................................ ................................ ............... 5 2. Findings ................................ ................................ ................................ ................ 6 2.1. Attitudes towards inclusive education ................................ .............................. 6 2.2. Teaching and learning practices ................................ ................................ ...... 7 2.3. Parents’ roles and expectations ................................ ................................ ....... 8 2.4. Communication issues ................................ ................................ ................... 11 2.5. Specialist support ................................ ................................ .......................... 11 2.6. Suggestions from respondents to make transition more inclusive ................. 12 3. Conclusions ................................ ................................ ................................ ....... -

External Evaluation of OHCHR Project “Combating Discrimination in the Republic of Moldova, Including in the Transnistrian Region” 2014-2015

External Evaluation of OHCHR Project “Combating Discrimination in the Republic of Moldova, including in the Transnistrian Region” 2014-2015 FINAL REPORT This report has been prepared by an external consultant. The views expressed herein are those of the consultant and therefore do not necessarily reflect the official opinion of the OHCHR. December 2015 Acknowledgments The evaluator of the OHCHR project “Combating Discrimination in the Republic of Moldova, including in the Transnistrian Region” is deeply grateful to the many individuals who made their time available for providing information, discussing and answering questions. In particular, the evaluator benefited extensively from the generous information and feedback from OHCHR colleagues and consultants in OHCHR Field Presence in Moldova and in OHCHR Geneva. The evaluator also had constructive meetings with groups of direct beneficiaries, associated project partners, national authorities, and UN colleagues in Moldova, including in the Transnistrian region. External Evaluator Mr. Bjorn Pettersson, Independent Consultant OHCHR Evaluation Reference Group Mrs. Jennifer Worrell (PPMES) Mrs. Sylta Georgiadis (PPMES) Mr. Sabas Monroy (PPMES) Mrs. Hulan Tsedev (FOTCD) Ms. Anita Trimaylova (FOTCD) Ms. Laure Beloin (DEXREL) Mr. Ferran Lloveras (OHCHR Brussels) Table of Contents Table of Contents ......................................................................................................................................... 3 List of Abbreviations .................................................................................................................................... -

2016 Human Rights Report

MOLDOVA 2016 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT Note: Unless otherwise noted, all references in this report exclude the secessionist region of Transnistria. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Moldova is a republic with a form of parliamentary democracy. The constitution provides for a multiparty democracy with legislative and executive branches as well as an independent judiciary and a clear separation of powers. Legislative authority is vested in the unicameral parliament. Pro-European parties retained a parliamentary majority in 2014 elections that met most Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE), Council of Europe, and other international commitments, although local and international observers raised concerns about the inclusion and exclusion of specific political parties. On January 20, a new government was formed after two failed attempts to nominate a candidate for prime minister. Opposition and civil society representatives criticized the government formation process as nontransparent. On March 4, the Constitutional Court ruled unconstitutional an amendment that empowered parliament to elect the president and reinstated presidential elections by direct and secret popular vote. Two rounds of presidential elections were held on October 30 and November 13, resulting in the election of Igor Dodon. According to the preliminary conclusions of the OSCE election observation mission, both rounds were fair and respected fundamental freedoms. International and domestic observers, however, noted polarized and unbalanced media coverage, harsh and intolerant rhetoric, lack of transparency in campaign financing, and instances of abuse of administrative resources. Civilian authorities maintained effective control over the security forces. Widespread corruption, especially within the judicial sector, continued to be the most significant human rights problem during the year. -

Moldova Is Strongly Marked by Self-Censorship and Partisanship

For economic or political reasons, journalism in Moldova is strongly marked by self-censorship and partisanship. A significant part of the population, especially those living in the villages, does not have access to a variety of information sources due to poverty. Profitable media still represent an exception rather than the rule. MoldoVA 166 MEDIA SUSTAINABILITY INDEX 2009 INTRODUCTION OVERALL SCORE: 1.81 M Parliamentary elections will take place at the beginning of 2009, which made 2008 a pre-election year. Although the Republic of Moldova has not managed to fulfill all of the EU-Moldova Action Plan commitments (which expired in February 2008), especially those concerning the independence of both the oldo Pmass media and judiciary, the Communist government has been trying to begin negotiations over a new agreement with the EU. This final agreement should lead to the establishment of more advanced relations compared to the current status of being simply an EU neighbor. On the other hand, steps have been taken to establish closer relations with Russia, which sought to improve its global image in the wake of its war with Georgia by addressing the Transnistria issue. Moldovan V authorities hoped that new Russian president Dmitri Medvedev would exert pressure upon Transnistria’s separatist leaders to accept the settlement project proposed by Chişinău. If this would have occurred, A the future parliamentary elections would have taken place throughout the entire territory of Moldova, including Transnistria. But this did not happen: Russia suggested that Moldova reconsider the settlement plan proposed in 2003 by Moscow, which stipulated, among other things, continuing deployment of Russian troops in Moldova in spite of commitments to withdraw them made at the 1999 OSCE summit. -

UNCTAD's National Green Export Review

UNITED NATIONS CONFERENCE ON TRADE AND DEVELOPMENT National Green Export Review of the Republic of Moldova: Walnuts, honey and cereals REPUBLIC OF MOLDOVA Photos credit: ©Fotolia.com Photos credit: © 2018, United Nations Conference on Trade and Development This work is available open access by complying with the Creative Commons licence created for intergovernmental organizations, available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/igo/. The findings, interpretations and conclusions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the United Nations or its officials or Member States. The designation employed and the presentation of material on any map in this work do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. This document has not been formally edited. UNCTAD/DITC/TED/2018/6 WALNUTS, HONEY AND CEREALS iii Contents Figures ....................................................................................................................................................iv Tables .....................................................................................................................................................iv Abbreviations ...........................................................................................................................................v Acknowledgements .................................................................................................................................v -

April-May 2005

Connections April-May 2005 For more information about any of the stories found in this issue please contact [email protected] Partner News • Renovated Tuberculosis Reference Laboratories Reopen in Moldova • Ukrainian Specialists Gain Knowledge to Provide Effective Treatment and Care to PLWHA • Tbilisi Workshop Provides PHC Partners with the Tools to Improve Clinical Management Skills Regional News • Russia Counts on Help from Pharmaceutical Companies to Improve Access to HIV/AIDS Medications • New Project to Control HIV/AIDS Launches in Uzbekistan • Treatment of Depression Can Increase Adherence to ART Workshops, Conferences, Opportunities and Grants • World AIDS Orphans' Day • International AIDS Candlelight Memorial Campaign • Conference on Rare Diseases and Orphan Drugs in Eastern European Countries • 2005 Annual Global Health Council Conference • 4th Congress of the World Society for Pediatric Infectious Diseases Features • St. Petersburg Conference Encourages Creation of Effective Russian National Model on HIV/AIDS Treatment and Care Partner News Renovated Tuberculosis Reference Laboratories Reopen in Moldova Under a brilliant sun that foreshadowed the approaching spring in Moldova, three tuberculosis reference laboratories recently reopened after extensive renovations. Three days of celebration and ceremony began with James P. Smith, executive director of AIHA, and Andrei Crusinschi, councilor to the Minister of Health of Moldova, cutting the ribbon at the Vorniceni Regional Reference Laboratory on the morning of March 24, World Stop TB Day. Numerous celebrants representing USAID, local government, and TB and primary healthcare services were greeted with traditional bread, salt, and wine as they entered the facility. Viorel Soltan— director of AIHA's USAID-funded Strengthening Tuberculosis Control in Moldova Project, which supports WHO's recommended Directly Observed Treatment-Short Course (DOTS) strategy for TB control—lauded the commitment the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, AIHA Executive Director James P. -

The Democratic Process: Promises and Challenges

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 480 425 SO 035 277 AUTHOR Bragaw, Donald, Ed. TITLE The Democratic Process: Promises and Challenges. INSTITUTION Street Law, Inc., Washington, DC.; Social Science Education Consortium, Inc., Boulder, CO.; Council of Chief State School Officers, Washington, DC.; Constitutional Rights Foundation, Los Angeles, CA.; Constitutional Rights Foundation, Chicago, IL.; American Forum for Global Education, New York, NY. SPONS AGENCY Office of Educational Research and Improvement (ED), Washington, DC. ISBN ISBN-0-94467-73-5 PUB DATE 2003-00-00 NOTE 230p.; A Resource Guide produced for the Democracy Education Exchange Project (DEEP). CONTRACT R304A010002B AVAILABLE FROM American Forum for Global Education, 120 Wall Street, Suite 2600, New York, NY 10005. Tel: 212-624-1300; Fax: 212-624- 1412; e-mail: [email protected]; Web site: http://www.globaled.org/. For full text: http://www.globaled.org/ DemProcess.pdf. PUB TYPE Books (010) Collected Works General (020) -- Guides Classroom Teacher (052) EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF01/PC10 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Democracy; *European History; Foreign Countries; *Geographic Regions; Global Education; Middle Schools; Secondary Education; Social Studies IDENTIFIERS *Europe (East) ABSTRACT When the Berlin Wall (East Germany) came down, it symbolically foretold the end of the Soviet Union domination of Eastern Europe and Central Asia. This resource guide examines the process toward democratization occurring in those regions. The guide updates the available classroom material on the democratic process. It is divided into three sections: (1) "Promises and Challenges" (contains five essays and nine lessons); (2) "Voices of Transition" (contains eight essays and eight lessons); and (3) "Fostering a Democratic Dialogue" (contains 3 essays and eight lessons) .Includes six maps. -

The Day the Bear Cowered: Russian Non-Intervention in the Baltics

The Day the Bear Cowered: Russian Non-Intervention in the Baltics Haverford Political Science Senior Thesis by Ian Wheeler Under Advisement of Prof. Barak Mendelsohn Table of Contents 1. Introduction ..........................................................................................................................1 2. Literature Review.................................................................................................................4 3. International Relations Theory ..........................................................................................15 4. Military Intervention ..........................................................................................................18 5. Spheres of Influence ..........................................................................................................20 6. Incentives for Intervention .................................................................................................25 7. Hypotheses .........................................................................................................................28 8. Methodology ......................................................................................................................33 9. Moldova Case Study Overview .........................................................................................38 10. Moldova Hypothesis Testing .............................................................................................46 11. Georgia Case Study Overview ...........................................................................................54 -

Can Moldova Stay on the Road to Europe

MEMO POL I CY CAN MOLDOVA STAY ON THE ROAD TO EUROPE? Stanislav Secrieru SUMMARY In 2013 Russia hit Moldova hard, imposing Moldova is considered a success story of the European sanctions on wine exports and fuelling Union’s Eastern Partnership (EaP) initiative. In the four separatist rumblings in Transnistria and years since a pro-European coalition came to power in 2009, Gagauzia. But 2014 will be much worse. Moldova has become more pluralist and has experienced Russia wants to undermine the one remaining “success story” of the Eastern Partnership robust economic growth. The government has introduced (Georgia being a unique case). It is not clear reforms and has deepened Moldova’s relations with the whether Moldova can rely on Ukraine as a EU, completing a visa-free action plan and initialling an buffer against Russian pressure, which is Association Agreement (AA) with provisions for a Deep and expected to ratchet up sharply after the Comprehensive Free Trade Agreement (DCFTA). At the start Sochi Olympics. Russia wants to change the Moldovan government at the elections due in of 2014, Moldova is one step away from progressing into a November 2014, or possibly even sooner; the more complex, more rewarding phase of relations with the Moldovan government wants to sign the key EU. Implementing the association agenda will spur economic EU agreements before then. growth and will multiply linkages with Moldova’s biggest trading partner, the EU. However, Moldova’s progress down Moldova is most fearful of moves against its estimated 300,000 migrant workers in the European path promises to be one of the main focuses Russia, and of existential escalation of the for intrigue in the region in 2014. -

Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Moldova: Does Moldova's Eastern Orientation Inhibit Its European Aspirations?

“Foreign affairs of the Republic of Moldova: Does Moldova’s Eastern orientation inhibit its European aspirations?” Liliana Viţu 1 CONTENTS: List of abbreviations Introduction Chapter I. Historic References…………………………………………………………p.1 Chapter II. The Eastern Vector of Moldova’s Foreign Affairs…………………..p.10 Russian Federation – The Big Brother…………………………………………………p.10 Commonwealth of Independent States: Russia as the hub, the rest as the spokes……………………………………………………….…………………………….p.13 Transnistria- the “black hole” of Europe………………………………………………..p.20 Ukraine – a “wait and see position”…………………………………………………….p.25 Chapter III. Moldova and the European Union: looking westwards?………….p.28 Romania and Moldova – the two Romanian states…………………………………..p.28 The Council of Europe - Monitoring Moldova………………………………………….p.31 European Union and Moldova: a missed opportunity?………………………………p.33 Chapter IV. Simultaneous integration in the CIS and the EU – a contradiction in terms ……………………………………………………………………………………...p.41 Conclusions Bibliography 2 LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS ASSMR – Autonomous Soviet Socialist Moldova Republic CEEC – Central-Eastern European countries CIS – Commonwealth of Independent States CoE – Council of Europe EBRD – European Bank for Reconstruction and Development ECHR – European Court of Human Rights EU – European Union ICG – International Crisis Group IPP – Institute for Public Policy NATO – North Atlantic Treaty Organisation NIS – Newly Independent States OSCE – Organisation for Security and Cooperation in Europe PCA – Partnership and Cooperation Agreement PHARE – Poland Hungary Assistant for Economic Reconstruction SECI – South East European Cooperation Initiative SPSEE – Stability Pact for South-Eastern Europe TACIS – Technical Assistance for Commonwealth of Independent States UNDP – United Nations Development Program WTO – World Trade Organization 3 INTRODUCTION The Republic of Moldova is a young state, created along with the other Newly Independent States (NIS) in 1991 after the implosion of the Soviet Union. -

Rapid Assessment of Trafficking in Children for Labour and Sexual Exploitation in Moldova

PROject of Technical assistance against the Labour and Sexual Exploitation of Children, including Trafficking, in countries of Central and Eastern Europe PROTECT CEE www.ilo.org/childlabour International Programme on the Elimination of Child Labour (IPEC) International Labour Office 4, Route des Morillons CH 1211 Geneva 22 Switzerland Rapid Assessment of Trafficking E-mail: [email protected] Tel: (+41 22) 799 81 81 in Children for Labour and Sexual Fax: (+41 22) 799 87 71 Exploitation in Moldova ILO-IPEC PROTECT CEE ROMANIA intr. Cristian popisteanu nr. 1-3, Intrarea D, et. 5, cam. 574, Sector 1, 010024-Bucharest, ROMANIA [email protected] Tel: +40 21 313 29 65 Fax: +40 21 312 52 72 2003 ISBN 92-2-116201-X IPEC International Programme on the Elimination of Child Labour Rapid Assessment of Trafficking in Children for Labour and Sexual Exploitation in Moldova Prepared by the Institute for Public Policy, Moldova Under technical supervision of FAFO Institute for Applied International Studies, Norway for the International Programme on the Elimination of Child Labour (IPEC) of the International Labour Organization (ILO) Chisinau, 2003 Copyright © International Labour Organization 2004 Publications of the International Labour Office enjoy copyright under Protocol 2 of the Universal Copyright Convention. Nevertheless, short excerpts from them may be reproduced without authorization, on condition that the source is indicated. For rights of reproduction or translation, application should be made to the ILO Publications Bureau (Rights and Permissions), -

Raionul Orhei

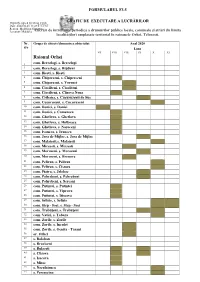

FORMULARUL F3.5 GRAFIC DE EXECUTARE A LUCRĂRILOR Lucrări de întreținere periodică a drumurilor publice locale, comunale și străzi (în limita localităților) amplasate teritorial în raioanele Orhei, Telenesti. Nr. Grupa de obiecte/denumirea obiectului Anul 2020 d/o Luna VII VIII VIII IX X XI Raionul Orhei 1 com. Berezlogi, s. Berezlogi 2 com. Berezlogi, s. Hijdieni 3 com. Biesti, s. Biesti 4 com. Chiperceni, s. Chiperceni 5 com. Chiperceni, s. Voronet 6 com. Ciocilteni, s. Ciocilteni 7 com. Ciocilteni, s. Clisova Noua 8 com. Crihana, s. Cucuruzenii de Sus 9 com. Cucuruzeni, s. Cucuruzeni 10 com. Donici, s. Donici 11 com. Donici, s. Camencea 12 com. Ghetlova, s. Ghetlova 13 com. Ghetlova, s. Hulboaca 14 com. Ghetlova, s. Noroceni 15 com. Ivancea, s. Ivancea 16 com. Jora de Mijloc, s. Jora de Mijloc 17 com. Malaiesti,s. Malaiesti 18 com. Mirzesti, s. Mirzesti 19 com. Morozeni, s. Morozeni 20 com. Morozeni, s. Brenova 21 com. Pelivan, s. Pelivan 22 com. Pelivan, s. Cismea 23 com. Piatra, s. Jeloboc 24 com. Pohrebeni, s. Pohrebeni 25 com. Pohrebeni, s. Sercani 26 com. Putintei, s. Putintei 27 com. Putintei, s. Viprova 28 com. Putintei, s. Discova 29 com. Seliste, s. Seliste 30 com. Step - Soci, s. Step - Soci 31 com. Trebujeni, s. Trebujeni 32 com. Vatici, s. Tabara 33 com. Zorile, s. Zorile 34 com. Zorile, s. Inculet 35 com. Zorile, s. Ocnita - Tarani 36 or. Orhei 37 s. Bolohan 38 s. Braviceni 39 s. Bulaesti 40 s. Clisova 41 s. Isacova 42 s. Mitoc 43 s. Neculaieuca 44 s. Peresecina 45 s.