York Potash Planning Application Tourism Commentary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Current Developments in Uk Mining Projects

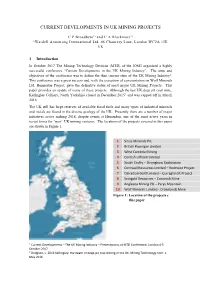

CURRENT DEVELOPMENTS IN UK MINING PROJECTS C P Broadbent1) and C A Blackmore1) 1)Wardell Armstrong International Ltd, 46 Chancery Lane, London WC2A 1JE, UK 1 Introduction In October 2017 The Mining Technology Division (MTD) of the IOM3 organised a highly successful conference “Current Developments in the UK Mining Industry”. The aims and objectives of the conference was to define the then current state of the UK Mining Industry1. This conference was a great success and, with the exception of a presentation on Wolf Minerals Ltd, Hemerdon Project, gave the definitive status of most major UK Mining Projects. This paper provides an update of many of these projects. Although the last UK deep pit coal mine, Kellingley Colliery, North Yorkshire closed in December 20152 and was capped off in March 2016. The UK still has large reserves of available fossil fuels and many types of industrial minerals and metals are found in the diverse geology of the UK. Presently there are a number of major initiatives active making 2018, despite events at Hemerdon, one of the most active years in recent times for “new” UK mining ventures. The locations of the projects covered in this paper are shown in Figure 1. 1) 1 Sirius Minerals Plc 2 British Fluorspar Limited 3 West Cumbria Mining 4 Cornish Lithium Limited 5 South Crofty – Strongbow Exploration 8 6 Cornwall Resources Limited – Redmoor Project 7 Dalradian Gold Limited – Curraghinalt Project 8 Scotgold Resources – Cononish Mine 7 3 1 9 Anglesea Mining Plc – Parys Mountain 10 Wolf Minerals Limited - Drakelands Mine 2 Figure 1: Location of the projects c 9 o vered in this paper this paper 10 6 4 5 1 Current Developments – The UK Mining Industry – Presentations at MTD Conference, London 4-5 October 2017 2 Dodgson, L. -

Rigg Farm Caravan Park Stainsacre, Whitby, North Yorkshire

RIGG FARM CARAVAN PARK STAINSACRE, WHITBY, NORTH YORKSHIRE CHARTERED SURVEYORS • AUCTIONEERS • VALUERS • LAND & ESTATE AGENTS • FINE ART & FURNITURE ESTABLISHED 1860 RIGG FARM CARAVAN PARK STAINSACRE WHITBY NORTH YORKSHIRE Robin Hoods Bay 3.5 miles, Whitby 3.5 miles, Scarborough 17 miles, York 45 miles,. (All distances approximates) A WELL PRESENTED CARAVAN PARK IN THE NORTH YORK MOORS NATIONAL PARK “Rigg Farm Caravan Park is an attractively situated caravan park located in an ideal position for tourists being located between Whitby and Robin Hoods Bay. The property comprises a period 4 bedroom house, attached barn with planning for an annexe, 30 pitch static caravan site, 9 pitch touring caravan site, camping area and associated amenity buildings, situated in around 4.65 acres of mature grounds” CARAVAN PARK: A well established and profitable caravan park set in attractive mature grounds with site licence and developed to provide 30 static pitches and 9 touring pitches. The site benefits from showers and W.C. facilities and offers potential for further development subject to consents. HOUSE: A surprisingly spacious period house with private garden areas. To the ground floor the property comprises: Utility/W.C., Kitchen, Pantry, Office, Conservatory, Dining Room, Living Room. To the first floor are three bedrooms and bathroom. ANNEXE: Attached to the house is an externally completed barn which has planning consent for an annexe and offers potential to develop as a holiday let or incorporate and extend into the main house LAND: In all the property sits within 4.65 acres of mature, well sheltered grounds and may offer potential for further development subject to consents. -

Whitby Area in Circulation Than Any Other Living Artist

FREE GUIDEBOOK 17th edition Gateway to the North York Moors National Park & Heritage Coast Ravenscar • Robin Hood’s Bay • Runswick Bay • Staithes Esk Valley • Captain Cook Country • Heartbeat Country Whitby & District Tourism Association www.visitwhitby.com Welcome to Whitby I am pleased to say that Whitby continues to attract a wide spectrum of visitors! This I believe is down to its Simpsons Jet Jewellery unique character forged at a time when the town was a relatively isolated community, self-reliant but welcoming of Whitby to anyone making the difficult journey by road or sea. Today, Whitby regularly features in the top ten surveys of Makers of fi ne quality Whitby Jet Jewellery UK holiday destinations. The range of interesting things to do, places to see and of course marvellous places to eat Tel: 01947 897166 both in the town itself and its surrounding villages are a major factor in this. Email: [email protected] As a town we continue to strive to improve your visitor experience. Whitby Town Council in partnership with We guarantee all our Jet is locally gathered and our Danfo rescued many of the public toilets from closure. Jet Jewellery is handmade in our workshop. They are now award winning! We’re easy to fi nd: Walk over the old Swing Bridge I hope this guidebook helps you to enjoy your visit and (with the Abbey in view). Turn right on to Grape Lane. tempts you to return to our lovely town and its wonderful We’re approximately halfway along on the right. surroundings again and again. -

Full Property Address Primary Liable

Full Property Address Primary Liable party name 2019 Opening Balance Current Relief Current RV Write on/off net effect 119, Westborough, Scarborough, North Yorkshire, YO11 1LP The Edinburgh Woollen Mill Ltd 35249.5 71500 4 Dnc Scaffolding, 62, Gladstone Lane, Scarborough, North Yorkshire, YO12 7BS Dnc Scaffolding Ltd 2352 4900 Ebony House, Queen Margarets Road, Scarborough, North Yorkshire, YO11 2YH Mj Builders Scarborough Ltd 6240 Small Business Relief England 13000 Walker & Hutton Store, Main Street, Irton, Scarborough, North Yorkshire, YO12 4RH Walker & Hutton Scarborough Ltd 780 Small Business Relief England 1625 Halfords Ltd, Seamer Road, Scarborough, North Yorkshire, YO12 4DH Halfords Ltd 49300 100000 1st 2nd & 3rd Floors, 39 - 40, Queen Street, Scarborough, North Yorkshire, YO11 1HQ Yorkshire Coast Workshops Ltd 10560 DISCRETIONARY RELIEF NON PROFIT MAKING 22000 Grosmont Co-Op, Front Street, Grosmont, Whitby, North Yorkshire, YO22 5QE Grosmont Coop Society Ltd 2119.9 DISCRETIONARY RURAL RATE RELIEF 4300 Dw Engineering, Cholmley Way, Whitby, North Yorkshire, YO22 4NJ At Cowen & Son Ltd 9600 20000 17, Pier Road, Whitby, North Yorkshire, YO21 3PU John Bull Confectioners Ltd 9360 19500 62 - 63, Westborough, Scarborough, North Yorkshire, YO11 1TS Winn & Co (Yorkshire) Ltd 12000 25000 Des Winks Cars Ltd, Hopper Hill Road, Scarborough, North Yorkshire, YO11 3YF Des Winks [Cars] Ltd 85289 173000 1, Aberdeen Walk, Scarborough, North Yorkshire, YO11 1BA Thomas Of York Ltd 23400 48750 Waste Transfer Station, Seamer, Scarborough, North Yorkshire, -

Anglo American Woodsmith Limited Annual Report and Financial Statements for the Year Ended 31 December 2019

Anglo American Woodsmith Limited Annual report and financial statements for the year ended 31 December 2019 Company number: 04948435 Contents Strategic Report Introduction 1 Our Project 4 Our Strategy 6 Our Product 9 Our Market 10 Our Business Model 11 Working responsibly 12 Delivering value to our stakeholders 18 Financial review 19 Risk management 21 Governance Remuneration Committee Report Annual Statement 25 Annual Report on Remuneration 26 Directors Remuneration Policy 38 Directors Report 45 Directors Responsibilities 49 Financial Statements Independent Auditors Report 51 Consolidated Statement of Comprehensive Income 59 Consolidated Statement of Financial Position 60 Consolidated Statement of Changes in Equity 61 Consolidated Statement of Cash Flows 62 Notes to the Consolidated Statements 63 Parent Company Statement of Financial Position 99 Parent Company Statement of Changes in Equity 100 Notes to the Parent Company Financial Statements 101 Additional Information Glossary 106 This Annual Report contains forward-looking statements. These forward-looking statements are made in good faith, based on a number of assumptions concerning future events and information available to the Directors at the time of their approval of this report. These forward-looking statements should be treated with caution due to the inherent uncertainties underlying any such forward looking information. The user of this document should not rely unduly on these forward-looking statements, which are not a guarantee of performance and which are subject to a number of uncertainties and other events, many of which are outside of the Company’s control and could cause actual events to differ materially from those in these statements. No guarantee can be given of future results, levels of activity, performance or achievements. -

Woodsmith Project Liaison Group Forum Project Update: October 2020

WOODSMITH PROJECT LIAISON GROUP FORUM PROJECT UPDATE: OCTOBER 2020 1. Construction update At Woodsmith Mine the focus remains on preparing the three shafts – service shaft, production shaft and minerals transport system (MTS) shaft – for the main shaft sinking. The Shaft Boring Roadheader (SBR) has been successfully installed in the service shaft at the depth of 120m ready to start shaft sinking by the end of the year. It will be boring down to a depth of 1,600m. The production foreshaft is complete and the excavation of the inner shaft has almost reached 120m. The SBR for this shaft is currently being assembled on site. For the MTS shaft, work is ongoing to fit-out and commission the Galloway, hoist and winch systems before the main shaft sinking starts by the end of the year. A drill and blast method will be used to sink this shaft and neighbours will soon be provided with information about the blasting notification procedure. With respect to the tunnel, the tunnel boring machine (TBM) - named Stella Rose by local school children - has made great progress and has now reached 9.5km on its way to Lockwood Beck. As the advance rate of the TBM has been greater than we anticipated, we are not planning to launch a second TBM from Lockwood and will continue with Stella Rose. This means that whilst we still need a shaft for ventilation at Lockwood Beck, it is now required to be 3.2m in diameter, which is smaller than initially proposed. The method that will be used to sink the shaft is called ‘blind boring’ and replaces the ‘drill and blast’ method previously proposed. -

Borough of Scarborough Visitor Economy Strategy & Destination Plan

BOROUGH OF SCARBOROUGH VISITOR ECONOMY STRATEGY & DESTINATION PLAN Consultation - October 2020 Visitor Economy Strategy and Destination Plan for the Borough of Scarborough 2 AN IMPORTANT NOTE ON CONSULTATION Under normal circumstances, this work would take place after extensive consultation with businesses within each destination, with a series of live workshops. Covid-19 has meant a different approach. We have used a combination of online discussions and online survey. We are now in the consultation phase, offering businesses and interested parties the opportunity to comment on the draft recommendations. Please remember this is a Draft Document, and subject to change following consultation with Scarborough Borough Council, businesses and relevant organisations. Please go to click here to add your comments. This version: 13th October 2020 Visitor Economy Strategy and Destination Plan for the Borough of Scarborough 3 Contents Page (To be added in final document) 1. Introduction 2. Strategic principles 3. Current visitors 4. Targets for future development 5. The Borough of Scarborough’s tourism product 6. Place-making and infrastructure improvements 7. Trends in Tourism 8. Impact of Brexit 9. Opportunities for product development 10. Target markets 11. Promotional themes 12. Events and festivals 13. Tackling seasonality 14. Collaborations and partnerships 15. Business support 16. Destination plans 17. Action Plan Visitor Economy Strategy and Destination Plan for the Borough of Scarborough 4 1. Introduction This strategy and destination plan has been commissioned by Scarborough Borough Council (SBC). The strategy is an update on the previous (2014-2024) Visitor Economy Strategy for the Borough of Scarborough, and was developed during the Covid-19 pandemic. -

Order 2010 Certificate of Ownership Under

TOWN & COUNTRY PLANNING (DEVELOPMENT MANAGEMENT PROCEDURE) (ENGLAND) ORDER 2010 CERTIFICATE OF OWNERSHIP UNDER ARTICLE 12 Certificate C: This Ownership Certificate is for use with applications and appeals for planning permission only . Two copies must be signed and dated and they in turn must be accompanied by two duly signed copies of the Agricultural Holdings Certificate in order for your planning application to be considered. I certify that: • The applicant cannot issue a Certificate A or B in respect of the accompanying application • The applicant has given the requisite notice to the persons specified below being persons who on the 21 days before the date of the application were owners of any part of the land to which the application relates. Owner’s name Address at which notice was served Date on which notice was served See appended list See appended list See appended list • The applicant has taken all reasonable steps open to them to find out the names and addresses of the other owners of the land, or of a part of it, but have has been unable to do so. These steps were as follows:- 1. Requested information from Land Registry 2. Conducted extensive enquiries both in the field and through solicitors, who conducted Title searches and investigations. • Notice of the application as attached to this Certificate, has been published in the Scarborough News, Teesside Gazette and Northern Echo on Thursday 18 th September 2014 and in the Whitby Gazette on Friday 19 th September 2014. Notices were also displayed in every parish within which there is situated any part of the land to which the application relates from the 16 th September 2014. -

7 November 2017 Mrs Claire Barber Acting Headteacher Hawsker Cum

Ofsted Piccadilly Gate Store Street Manchester T 0300 123 4234 M1 2WD www.gov.uk/ofsted 7 November 2017 Mrs Claire Barber Acting headteacher Hawsker Cum Stainsacre Church of England Voluntary Controlled Primary School Hawsker Whitby North Yorkshire YO22 4LA Dear Mrs Barber Short inspection of Hawsker Cum Stainsacre Church of England Voluntary Controlled Primary School Following my visit to the school on 17 October 2017, I write on behalf of Her Majesty’s Chief Inspector of Education, Children’s Services and Skills to report the inspection findings. The visit was the first short inspection carried out since the school was judged to be good in June 2013. This school continues to be good. Leaders have maintained the good quality of education in the school since the last inspection. The school has experienced considerable changes in leadership and staffing over the last year during the long-term absence of the substantive headteacher. The effective partnership between school leaders, governors, the local authority and the diocese has ensured that the quality of education and care of the pupils have been of the upmost importance during these changes. Outcomes for pupils continue to be strong. Pupils enjoy their learning and speak proudly of their school and their friendships. They show support and respect for each other. They say that staff make their learning fun and that they feel well cared for. Most parents and carers have a positive view of the learning experiences that their children have. They say that communication about their child’s progress and events in the school is good. -

AA Press Release HY 2021

HALF YEAR FINANCIAL REPORT for the six months ended 30 June 2021 This page has been intentionally left blank. 29 July 2021 Anglo American Interim Results 2021 Strong market demand and operational resilience deliver underlying EBITDA of $12.1 billion Financial highlights for the six months ended 30 June 2021 • Underlying EBITDA* of $12.1 billion, driven by strong market demand and operational resilience • Profit attributable to equity shareholders of $5.2 billion • Net debt* of $2.0 billion (0.1 x annualised underlying EBITDA), reflecting strong cash generation • $4.1 billion shareholder return, reflecting capital discipline and commitment to return excess cash: ◦ $2.1 billion interim dividend, equal to $1.71 per share, consistent with our 40% payout policy ◦ $2.0 billion additional return: $1.0 billion special dividend and $1.0 billion share buyback • Exit from thermal coal operations: Thungela demerger completed and sale of Cerrejón interest announced Mark Cutifani, Chief Executive of Anglo American, said: “The first six months of 2021 have seen strong demand and prices for many of our products as economies begin to recoup lost ground, spurred by stimulus measures across the major economies. The platinum group metals and copper – essential to the global decarbonisation imperative as we electrify transport and harness clean, renewable energy – and premium quality iron ore for greener steelmaking, supported by an improving market for diamonds, all contributed to a record half year financial performance, generating underlying EBITDA of $12.1 billion. “Against a backdrop of ongoing Covid hardships in many countries, our commitment to do everything we can to help protect our people and communities stands firm. -

Woodsmith Mine, North Yorkshire Moors

Woodsmith Mine, North Yorkshire Moors Woodsmith Mine, located near to the A sensitive project, having attracted and one for launching the 5m diameter hamlet of Sneatonthorpe, Whitby in many objections along the way, tunnel boring machines (TBM) that will North Yorkshire, is a deep potash and developing the mine to extract the drive the first section of the 37km polyhalite mine, a venture started by material from 1.5km below the moors material transport system (MTS) tunnel York Potash Ltd, which later became a with minimal impact, was always going at 360m depth from Woodsmith to subsidiary of Sirius Minerals plc, whose to require some complex ground Teeside. primary focus is the development of the engineering solutions. The geotechnical With these requirements, Bauer polyhalite project. challenges and the many programme Technologies was appointed to install The project involves Sirius Minerals changes required to bring the mine live three up to 120m deep diaphragm constructing the UK’s deepest mine, by early 2021, which is some six months wall shafts, with diameters between 8m which over the next five years will see earlier than originally planned, meant it and 35m. To guarantee the specified the company extract large quantities of is an evolving project. To comply with vertical tolerance of 200mm, the site Polyhalite for global distribution. Beyond planning the mine also had to be low team had to combine various survey this, the mine is expected to have a impact, which restricted it to having methods, which were documented in life of at least 100 years and has been only two 60m deep chambers to house a 3D BIM model. -

Sirius Minerals ' US$425M Offering Closes Oversubscribed SNL Metals & Mining Daily: West Edition

Sirius raises £330m Evening Gazette Sirius Minerals ' US$425M offering closes oversubscribed SNL Metals & Mining Daily: West Edition Sirius puts £5m into protecting local area Evening Gazette Funding for local area from Sirius Minerals hits £5m - and 10m new trees are on the way gazettelive.co.uk Sirius Minerals raises almost £330m in latest round of fundraising gazettelive.co.uk Sirius Minerals says there is strong equity market support' for fundraising to create giant Yorkshire mine Yorkshire Post News Sirius raises £330m ian mcneal 308 words 23 May 2019 Evening Gazette EVEGAZ 1; National 16 English © 2019 Gazette Media Company Ltd. All Rights Reserved. Page 1 © 2019 Factiva, Inc. All rights reserved. SIRIUS Minerals has raised almost £330m in a new share issue in the latest round of fundraising to develop its mine. The company unveiled plans in April to raise £3bn to fund the next stage of its North Yorkshire mine in the form of new shares and debt. Work is continuing on Woodsmith mine, south of Whitby, from where polyhalite will be transported on an underground conveyor to Teesside. Sirius currently employs 800 people and says it will create 1,000 long-term jobs at peak production. The company provided an update to investors on Tuesday on its placing and open share offer, which it said was oversubscribed. A total of £327m was raised after the issue of 218 million shares at 15p each. Chris Fraser, managing director and chief executive, said: "We are encouraged by the oversubscribed open offer, which underlines the strong equity market support for our comprehensive markets-led solution for stage 2 funding.