Extract from Australian Broadcasting Corporation Website Gallipoli the First Day

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gallipoli Campaign

tHe GaLlIpOlI CaMpAiGn The Gallipoli Campaign was an attack on the Gallipoli peninsula during World War I, between 25 April 1915 and 9 January 1916. The Gallipoli peninsula was an important tactical position during World War I. The British War Council suggested that Germany could be defeated by attacks on her allies, Austria, Hungary and Turkey. The Allied forces of the British Empire (including Australia and New Zealand) aimed to force a passage through the Dardanelles Strait and capture the Turkish capital, Constantinople. At dawn on 25 April 1915, Anzac assault troops landed north of Gaba Tepe, at what became known as Anzac Cove, while the British forces landed at Cape Helles on the Gallipoli Peninsula. The campaign was a brave but costly failure. By December 1915 plans were drawn up to evacuate the entire force from Gallipoli. On 19 and 20 December, the evacuation of over 142,000 men from Anzac Cove commenced and was completed three weeks later with minimal casualties. In total, the whole Gallipoli campaign caused 26,111 Australian casualties, including 8,141 deaths. Since 1916 the anniversary of the landings on 25 April has been commemorated as Anzac Day, becoming one of the most important national celebrations in Australia and New Zealand. tHe GaLlIpOlI CaMpAiGn The Gallipoli Campaign was an attack on the Gallipoli peninsula during World War I, between 25 April 1915 and 9 January 1916. The Gallipoli peninsula was an important tactical position during World War I. The British War Council suggested that Germany could be defeated by attacks on her allies, Austria, Hungary and Turkey. -

“Come on Lads”

“COME ON LADS” ON “COME “COME ON LADS” Old Wesley Collegians and the Gallipoli Campaign Philip J Powell Philip J Powell FOREWORD Congratulations, Philip Powell, for producing this short history. It brings to life the experiences of many Old Boys who died at Gallipoli and some who survived, only to be fatally wounded in the trenches or no-man’s land of the western front. Wesley annually honoured these names, even after the Second World War was over. The silence in Adamson Hall as name after name was read aloud, almost like a slow drum beat, is still in the mind, some seventy or more years later. The messages written by these young men, or about them, are evocative. Even the more humdrum and everyday letters capture, above the noise and tension, the courage. It is as if the soldiers, though dead, are alive. Geoffrey Blainey AC (OW1947) Front cover image: Anzac Cove - 1915 Australian War Memorial P10505.001 First published March 2015. This electronic edition updated February 2017. Copyright by Philip J Powell and Wesley College © ISBN: 978-0-646-93777-9 CONTENTS Introduction .................................................................................. 2 Map of Gallipoli battlefields ........................................................ 4 The Real Anzacs .......................................................................... 5 Chapter 1. The Landing ............................................................... 6 Chapter 2. Helles and the Second Battle of Krithia ..................... 14 Chapter 3. Stalemate #1 .............................................................. -

The Forgotten Fronts the First World War Battlefield Guide: World War Battlefield First the the Forgotten Fronts Forgotten The

Ed 1 Nov 2016 1 Nov Ed The First World War Battlefield Guide: Volume 2 The Forgotten Fronts The First Battlefield War World Guide: The Forgotten Fronts Creative Media Design ADR005472 Edition 1 November 2016 THE FORGOTTEN FRONTS | i The First World War Battlefield Guide: Volume 2 The British Army Campaign Guide to the Forgotten Fronts of the First World War 1st Edition November 2016 Acknowledgement The publisher wishes to acknowledge the assistance of the following organisations in providing text, images, multimedia links and sketch maps for this volume: Defence Geographic Centre, Imperial War Museum, Army Historical Branch, Air Historical Branch, Army Records Society,National Portrait Gallery, Tank Museum, National Army Museum, Royal Green Jackets Museum,Shepard Trust, Royal Australian Navy, Australian Defence, Royal Artillery Historical Trust, National Archive, Canadian War Museum, National Archives of Canada, The Times, RAF Museum, Wikimedia Commons, USAF, US Library of Congress. The Cover Images Front Cover: (1) Wounded soldier of the 10th Battalion, Black Watch being carried out of a communication trench on the ‘Birdcage’ Line near Salonika, February 1916 © IWM; (2) The advance through Palestine and the Battle of Megiddo: A sergeant directs orders whilst standing on one of the wooden saddles of the Camel Transport Corps © IWM (3) Soldiers of the Royal Army Service Corps outside a Field Ambulance Station. © IWM Inside Front Cover: Helles Memorial, Gallipoli © Barbara Taylor Back Cover: ‘Blood Swept Lands and Seas of Red’ at the Tower of London © Julia Gavin ii | THE FORGOTTEN FRONTS THE FORGOTTEN FRONTS | iii ISBN: 978-1-874346-46-3 First published in November 2016 by Creative Media Designs, Army Headquarters, Andover. -

ANZAC Day Resources

ANZAC Day Worship Resource Content Preface …3 Introduction …4 Service of Remembrance …5 Gathering …6 Word ...13 Remembrance …17 Sending …24 General Prayers …26 Hymn Suggestions …30 Public Services …33 Images Front Page 3rd Light Horse Chap Merrington 1915 Gallipoli Page 3 3rd Light Horse Burial ANZAC Day 1917 Cairo Page 5 1st Light Horse Funeral at Cairo Presbyterian Cemetary 1914-15 Page 6 CoE RC and Presb. Chaplains bury four British soldiers 1915 Page 13 Church parade at Ryrie's Post 1915 Gallipoli Page 17 3rd Light Horse Chap Merrington 1915 Gallipoli Page 25 Grave of an Australian Soldier 1915 Gallipoli Page 27 Soldiers on Gallipoli listening to sermon 1915 Page 31 Chaplain writing field card Greece, Date Unknown Page 34 Brockton WA WW! Memorial after ANZAC Day Service !2 Preface This resource has been compiled by Uniting Church in Australia ministers who are current- ly in placement as Chaplains in the Australian Defence Force. Some of them have seen deployments in places of war and served for many years while others are new to this min- istry who care for sailors, soldiers and airmen and women in the ADF and their families. These traditional and interactive prayers have been provided for congregations that will be remembering Australians throughout the centenary year of World War 1 and in particular the landings at Gallipoli. The prayers in this resource have been broken up in light of the four fold structure of wor- ship, as found in Uniting in Worship 2: Gathering, Word, Remembrance, and Sending. There is a fifth section which has been compiled from prayers used by Chaplains in public services, such as ANZAC Days and Remembrance Days. -

Catalogue: May #2

CATALOGUE: MAY #2 MOSTLY OTTOMAN EMPIRE, THE BALKANS, ARMENIA AND THE MIDDLE EAST - Books, Maps & Atlases 19th & 20th Centuries www.pahor.de 1. COSTUMES OF THE OTTOMAN EMPIRE A small, well made drawing represents six costumes of the Ottoman Empire and the Middle East. The numeration in the lower part indicates, that the drawing was perhaps made to accompany a Anon. [Probably European artist]. text. S.l., s.d. [Probably mid 19th century] Pencil and watercolour on paper (9,5 x 16,5 cm / 3.7 x 6.5 inches), with edges mounted on 220 EUR later thick paper (28 x 37,5 cm / 11 x 14,8 inches) with a hand-drawn margins (very good, minor foxing and staining). 2. GREECE Anon. [Probably a British traveller]. A well made drawing represents a Greek house, indicated with a title as a house between the port city Piraeus and nearby Athens, with men in local costumes and a man and two young girls in House Between Piraeus and Athens. central or west European clothing. S.l., s.d. [Probably mid 19th century]. The drawing was perhaps made by one of the British travellers, who more frequently visited Black ink on thick paper, image: 17 x 28 cm (6.7 x 11 inches), sheet: 27 x 38,5 cm (10.6 x 15.2 Greece in the period after Britain helped the country with its independence. inches), (minor staining in margins, otherwise in a good condition). 160 EUR 3. OTTOMAN GEOLOGICAL MAP OF TURKEY: Historical Context: The Rise of Turkey out of the Ottoman Ashes Damat KENAN & Ahmet Malik SAYAR (1892 - 1965). -

The Long Road to Anzac Cove: Chronology Task Lesson

LESSON TWO THE LONG ROAD TO ANZAC COVE: CHRONOLOGY TASK Visit https://www.vic.gov.au/ premiers-spirit-anzac-prize for further information 2 Lesson 2: The Long Road to Anzac Cove: Chronology Task The Long Road to Anzac Cove: Chronology Task The organising of dates and events into the order in which they occurred is called chronology. It is important to us as historians, as knowing when something happened can help us evaluate the significance, impact or outcome of a person, object or event. Chronology can also help us with our understanding of the reasons for historical continuity and change, and of cause and effect, so we can fully understand the context of an historical event, in this case the Gallipoli campaign. Task One: Flow Chart The statements below, which outline the ANZAC troops’ road to Gallipoli, are all jumbled. Using an online flowchart tool or pen and paper, create a flowchart that shows the events in the correct order. [Hint: You will need to read each statement carefully to be able to work out the correct order. Use the dates to help you and then you will need to infer the order by examining each statement logically. You have enough information on this page to work out the correct chronology.] 01 March 22 1915, the Gallipoli offensive is being planned. 02 When off duty, according to historian Charles Bean, ‘to many a young Australian [being in Cairo] seemed a place for unlimited holiday.’ 03 Troops disembarked in Alexandria on 3 December and proceeded to their camp in Cairo, near the Pyramids of Giza. -

7-9 Booklist by Title - Full

7-9 Booklist by Title - Full When using this booklist, please be aware of the need for guidance to ensure students select texts considered appropriate for their age, interest and maturity levels. This title also appears on the 9plus booklist. This title is usually read by students in years 9, 10 and above. PRC Title/Author Publisher Year ISBN Annotations 5638 1000-year-old boy, The HarperCollins 2018 9780008256944 Alfie Monk is like any other pre-teen, except he's 1000 years old and Welford, Ross Children's Books can remember when Vikings invaded his village and he and his family had to run for their lives. When he loses everything he loves in a tragic fire and the modern world finally catches up with him, Alfie embarks on a mission to change everything by finally trusting Aidan and Roxy enough to share his story, and enlisting their help to find a way to, eventually, make sure he will eventually die. 22034 13 days of midnight Orchard Books 2015 9781408337462 Luke Manchett is 16 years old with a place on the rugby team and the Hunt, Leo prettiest girl in Year 11 in his sights. Then his estranged father suddenly dies and he finds out that he is to inherit six million dollars! But if he wants the cash, he must accept the Host. A collection of malignant ghosts who his Necromancer father had trapped and enslaved! Now the Host is angry, the Host is strong, and the Host is out for revenge! Has Luke got what it takes to fight these horrifying spirits and save himself and his world? 570824 13th reality, The: Blade of shattered hope Scholastic Australia 2018 9781742998381 Tick and his friends are still trying to work out how to defeat Mistress Dashner, James Jane, but when there are 13 realities from which to draw trouble, the battle is 13 times as hard. -

Letter from a Pilgrimage 8 2

LETTERS FROM A PILGRIMAGE Ken Inglis’s despatches from the Anzac tour to Gallipoli, April–May 1965 LETTERS FROM A PILGRIMAGE Ken Inglis’s despatches from the Anzac tour of Greece and Turkey, April–May 1965 First published in e Canberra Times, 15 April–1 May 1965 Republished by Inside Story, April 2015 Ken Inglis is Emeritus Professor (History) at the Australian National University and an Honorary Professor in the National Centre for Australian Studies at Monash University. He has published widely on the Anzac tradition and intellectual history. He travelled with the Anzac Pilgrims in 1965 as correspondent for e Canberra Times. Cover: Anzacs going ashore at dawn on 25 April 1965. Photo: Ken Inglis Preface adapted from Observing Australia: 1959 to 1999, by K.S. Inglis, edited and introduced by Craig Wilcox, Melbourne University Press, 1999 DOI 10.4225/50/5535D349F3180 Inside Story Swinburne Institute for Social Research PO Box 218, Hawthorn, Victoria 3122 insidestory.org.au Contents Preface 5 1. Letter from a pilgrimage 8 2. Anzac Diggers see Tobruk and cheer 15 3. Why they came 21 4. Nasser earns the Anzacs’ admiration 24 5. Stepping ashore tomorrow on Australia’s “holy land” 31 6. Anzacs play to Turkish rules on their return 38 7. 10,000 miles and back to commune with Anzac dead 45 4 Preface n 1965 the Returned Services League, or RSL, and its New Zealand equivalent sponsored a three-week cruise around the Mediterranean arranged by Swan Hellenic Tours, vis- iting sites of significance in Anzac memory and culminat- ing in a landing at Anzac Cove on the fiftieth anniversary Iof the first one. -

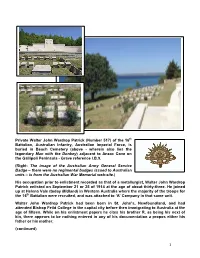

Patrick, Walter John Wardrop

Private Walter John Wardrop Patrick (Number 517) of the 16th Battalion, Australian Infantry, Australian Imperial Force, is buried in Beach Cemetery (above - wherein also lies the legendary Man with the Donkey) adjacent to Anzac Cove on the Gallipoli Peninsula - Grave reference I.B.9. (Right: The image of the Australian Army General Service Badge – there were no regimental badges issued to Australian units – is from the Australian War Memorial web-site.) His occupation prior to enlistment recorded as that of a metallurgist, Walter John Wardrop Patrick enlisted on September 21 or 25 of 1914 at the age of about thirty-three. He joined up at Helena Vale (today Midland) in Western Australia where the majority of the troops for the 16th Battalion were recruited, and was attached to ‘A’ Company in that same unit. Walter John Wardrop Patrick had been born in St. John’s, Newfoundland, and had attended Bishop Feild College in the capital city before then immigrating to Australia at the age of fifteen. While on his enlistment papers he cites his brother R. as being his next of kin, there appears to be nothing entered in any of his documentation a propos either his father or his mother. (continued) 1 It was on December 22 of that same year that the personnel of the 16th Battalion – thirty-two officers and nine-hundred seventy-nine other ranks, among that number Private Patrick – embarked in the port of Melbourne onto His Majesty’s Australian Transport Ceramic for passage to the Middle East. It was to be a six-week journey. -

ANZAC Day Simon Moss What Are We Remembering?

14 field report/issue ANZAC Day Simon Moss What are we remembering? As I flicked through media coverage of ANZAC Day from recent years, I felt proud to think of myself as an Australian. The pages and airwaves were filled with inspiring stories of bravery and courage from those who had offered themselves up for a greater cause, some paying the ultimate price. April 25, the anniversary of the ANZAC landing at Gallipoli, has come to be a day of commemoration and remembrance for those who fought and died for Australia. This year’, ANZAC Day stood to take on even more significance, with active troops stationed in Iraq, and the dawn of a new era following the passing away last year of the last ANZAC veteran. And so, early on a cool autumn morning, twenty thousand Melburnians gathered at the Shrine of Remembrance for the Dawn Service, myself amongst them. Scanning faces in the dim predawn light, I was taken aback to see how many young people, our age, who were at the service. And listening to the simple yet profound words of the service, I wondered, “Why is ANZAC day important? What are we remembering?” A simple answer came to mind - remembering those who died for their country. But that seemed too simple, these wars are long past. There had to be something more, something greater than the memory of single people, an idea that would span generations and bring people together. The ANZAC spirit. In context, the Anzac spirit emerges from a disastrous military campaign that started in a hail of bullets from above, as the troops were landed at the base of the cliffs of Ari Burnu, instead of the beaches to the south. -

2015 the CENTENARY ISSUE Marking the 100Th Anniversary of the Gallipoli Landings

TheThe GallipolianGallipolian The Journal of the Gallipoli Association No. 137 - SPRING 2015 THE CENTENARY ISSUE Marking the 100th Anniversary of The Gallipoli Landings The River Clyde at V Beach, 25 April, 1915 by Charles Dixon - reproduced by kind permission of The Princess of Wales’s Royal Regiment (Queen’s and Royal Hampshires) SPRING2015 12/3/15 09:39 Page ii THE GALLIPOLIAN The Journal of the Gallipoli Association founded by Major E H W Banner in 1969 on the Campaign of 1915 The Gallipoli Association Registered Charity No. 1155609 Mailbox 630, Wey House, 15 Church Street, Weybridge KT13 8NA WEBSITE http://www.gallipoli-assocation.org PATRON HRH The Duke of Edinburgh KG KT PAST PRESIDENTS The Lord Granville of Eye Vice-Admiral E W Longley-Cook CB CBE DSO Lt. General Sir Reginald Savory KCMG KCIE DSO MC Brigadier B B Rackham CBE MC Lt Colonel M E Hancock MC TRUSTEES Chairman: Captain C T F Fagan DL Secretary: James C Watson Smith, Chelsea Lodge, Coopers Hill Lane, Englefield Green, Surrey TW20 0JX. Tel: 01784 479148. E-mail: [email protected] Treasurer: Mrs Vicki Genrich, , 78 Foxbourne Road, London SW17 8EW E-mail: treasurer @gallipoli-association.org Membership Secretary & General Enquiries: Mr Keith Edmonds 4 Duck End, Godmanchester, Huntingdon PE29 2LW Tel: 01480.450665 E-mail: [email protected] Editor: Foster Summerson, 23 Tavnaghan Lane, Cushendall, Ballymena BT44 0SY Tel: 028.217.72996. E-mail: [email protected] Webmaster & Historian: Stephen Chambers E-mail: [email protected] Major Hugh Jenner, Brigadier J R H Stopford ———————————————————— Other appointments: Historian Panel: Enquiries should be directed to: [email protected] Gallipoli 100 Sub-Committee: Lt. -

Teacher's Kit GALLIPOLI.Pdf

GALLIPOLI SCHOOLSDAY PERFORMANCE IMPORTANT INFORMATION Date: Wednesday 13th August 2008 Venue: Sydney Theatre Pre-performance forum 10.30 am Lunch Break 11.15 am Performance commences: 12.15 pm Performance concludes: 3.15 pm We respectfully ask that you discuss theatre etiquette with your students prior to coming to the performance. Running Late? Please contact Sydney Theatre Company’s main switch on 9250 1700 and a message will be passed to Front of House. Booking Queries Please contact Marietta Hargreaves on 02 9250 1778 or [email protected] General Education Queries Please contact Helen Hristofski, Education Manager, on 02 9250 1726 or [email protected] Sydney Theatre Company’s GALLIPOLI Teacher’s Notes compiled by Elizabeth Surbey © 2008 1 Sydney Theatre Company presents the STC Actors Company in GALLIPOLI Written and Devised by Nigel Jamieson in association with the Cast Teacher's Resource Kit Written and compiled by Elizabeth Surbey Sydney Theatre Company’s GALLIPOLI Teacher’s Notes compiled by Elizabeth Surbey © 2008 2 Acknowledgements Sydney Theatre Company would like to thank the following for their invaluable material for these Teachers' Notes: Laura Scrivano (STC) Helen Hristofski (STC) Copyright Copyright protects this Teacher’s Resource Kit. Except for purposes permitted by the Copyright Act, reproduction by whatever means is prohibited. However, limited photocopying for classroom use only is permitted by educational institutions. Front Image of Alec Campbell used by kind permission of the Campbell