DI NH14 F4 Ocrcombined.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Analysis of Hawaiʻi‟S Cultural Impact Assessment Process As a Vehicle of Environmental Justice for Kānaka Maoli

Innovation or Degradation?: An Analysis of Hawaiʻi‟s Cultural Impact Assessment Process as a Vehicle of Environmental Justice for Kānaka Maoli Elena Bryant* INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................ 231 I. PROVIDING A FRAMEWORK: ENVIRONMENTAL JUSTICE FOR KĀNAKA MAOLI COMMUNITIES ........................................................ 235 A. Incorporating Environmental Justice into Hawaiʻi‟s EIS Process: Racializing Environmental Justice ........................... 236 B. Defining the “Injustice” ........................................................... 238 C. The Enactment of Natural and Cultural Resource Protections as a Mechanism for Restorative Justice for Kānaka Maoli ..... 244 II. THE CULTURAL AND HISTORICAL SIGNIFICANCE OF WIND AND WATER TO KĀNAKA MAOLI .............................................................. 245 A. Kumulipo: Kānaka Maoli‟s Source of Origin .......................... 246 B. “I paʻa i ke Kalo ʻaʻole ʻoe e puka; If it had ended with the Kalo you would not be here.” ................................................... 247 C. Cultural Significance of the Wind ............................................. 248 D. Cultural Significance of the Sea ............................................... 250 III. THE PUSH TO “GO GREEN”: HAWAIʻI‟S INTERISLAND WIND PROJECT ........................................................................................... 252 A. Hawaiʻi Clean Energy Initiative: Moving Hawaiʻi Towards Energy Self-sufficiency ............................................................ -

AMERICA's ANNEXATION of HAWAII by BECKY L. BRUCE

A LUSCIOUS FRUIT: AMERICA’S ANNEXATION OF HAWAII by BECKY L. BRUCE HOWARD JONES, COMMITTEE CHAIR JOSEPH A. FRY KARI FREDERICKSON LISA LIDQUIST-DORR STEVEN BUNKER A DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History in the Graduate School of The University of Alabama TUSCALOOSA, ALABAMA 2012 Copyright Becky L. Bruce 2012 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT This dissertation argues that the annexation of Hawaii was not the result of an aggressive move by the United States to gain coaling stations or foreign markets, nor was it a means of preempting other foreign nations from acquiring the island or mending a psychic wound in the United States. Rather, the acquisition was the result of a seventy-year relationship brokered by Americans living on the islands and entered into by two nations attempting to find their place in the international system. Foreign policy decisions by both nations led to an increasingly dependent relationship linking Hawaii’s stability to the U.S. economy and the United States’ world power status to its access to Hawaiian ports. Analysis of this seventy-year relationship changed over time as the two nations evolved within the world system. In an attempt to maintain independence, the Hawaiian monarchy had introduced a westernized political and economic system to the islands to gain international recognition as a nation-state. This new system created a highly partisan atmosphere between natives and foreign residents who overthrew the monarchy to preserve their personal status against a rising native political challenge. These men then applied for annexation to the United States, forcing Washington to confront the final obstacle in its rise to first-tier status: its own reluctance to assume the burdens and responsibilities of an imperial policy abroad. -

BROKEN PROMISES: Continuing Federal Funding Shortfall for Native Americans

U.S. COMMISSION ON CIVIL RIGHTS BROKEN PROMISES: Continuing Federal Funding Shortfall for Native Americans BRIEFING REPORT U.S. COMMISSION ON CIVIL RIGHTS Washington, DC 20425 Official Business DECEMBER 2018 Penalty for Private Use $300 Visit us on the Web: www.usccr.gov U.S. COMMISSION ON CIVIL RIGHTS MEMBERS OF THE COMMISSION The U.S. Commission on Civil Rights is an independent, Catherine E. Lhamon, Chairperson bipartisan agency established by Congress in 1957. It is Patricia Timmons-Goodson, Vice Chairperson directed to: Debo P. Adegbile Gail L. Heriot • Investigate complaints alleging that citizens are Peter N. Kirsanow being deprived of their right to vote by reason of their David Kladney race, color, religion, sex, age, disability, or national Karen Narasaki origin, or by reason of fraudulent practices. Michael Yaki • Study and collect information relating to discrimination or a denial of equal protection of the laws under the Constitution Mauro Morales, Staff Director because of race, color, religion, sex, age, disability, or national origin, or in the administration of justice. • Appraise federal laws and policies with respect to U.S. Commission on Civil Rights discrimination or denial of equal protection of the laws 1331 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW because of race, color, religion, sex, age, disability, or Washington, DC 20425 national origin, or in the administration of justice. (202) 376-8128 voice • Serve as a national clearinghouse for information TTY Relay: 711 in respect to discrimination or denial of equal protection of the laws because of race, color, www.usccr.gov religion, sex, age, disability, or national origin. • Submit reports, findings, and recommendations to the President and Congress. -

Plotting of the Overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom

American Politics: Plotting the Illegal Hawaiian Kingdom Overthrow and Illegal Annexation After the Civil War of 1861-1865 the Kingdom of Hawai’i was already in the crosshairs of more serious US annexation. The country was flush with money from unspent taxes imposed during the Civil War. It was secured from coast to coast and the Presidency was securely in the hands of Republican Union Civil War veterans who had defeated the secessionist Southern States Democrats and looked for expansion into the Pacific under their doctrine of divine destiny. The navy was expanded with iron warships and two of them under the command of Major General Schofield and Colonel Alexander had visited Honolulu in 1873 under the guise of a “friendly mission,” spying on the kingdom and mapping out the potential of Pearl Harbor as a navy base for expansion into the Pacific. In 1840 US Navy Commodore Charles Wilkes had first surveyed the Pearl Harbor area and described it as “the best and most capacious harbor in the Pacific.” Grover Cleveland, the leader of the pro-business Democrats, opposed imperialism, high tariffs, inflation, and subsidies and had established a reputation for relentlessly fighting the widespread political corruption of both the Democratic and Republican parties. Not actually running for president, he was unexpectedly chosen by his Democratic party as a compromise candidate and also unexpectedly won the presidential election, as the public had become sick of the widespread political corruption. He therefore won his first term in 1884 at a time of Republican political domination dating to 1861 which had become pro imperialistic and clamored for colonial expansion. -

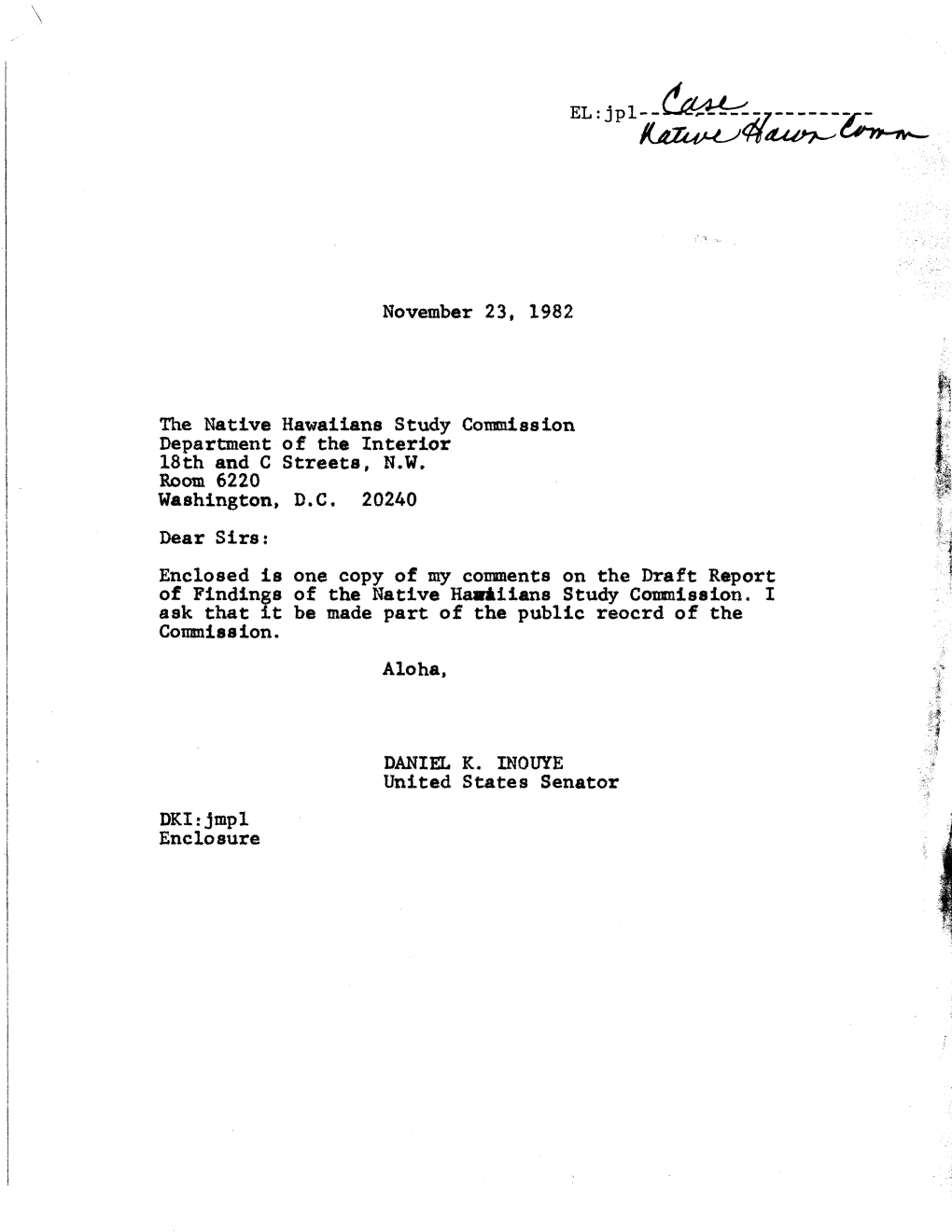

Native Hawaiians Study Commission.: Report Onthe TITLE , Culture, Needs and Concerns of Nativehawaiians

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 254 609 UD 024'136 Native Hawaiians Study Commission.: Report onthe TITLE , Culture, Needs and Concerns of NativeHawaiians. Final ort. Volume II.Claims of Conscience: A Dissenting Study\ofs the Culture, Needs andConcerns of Native HawaiianS. , INSTITUTION Department of the Interior,Washington, D.C. PUB DATE 23 Jun 83 ° NOTE 194p.; For Volume Iof the final-report, see UD 024 135. PUB TYPE Reports -'Researcb/Technical (143r EDRS PRICE MF01/PC08 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Federal Legislationl *Federal,StateRelationship; *Hawailans,"Legal Responsibility; *Needs Assessment; *State History; *Trust Responsibility (Government); United States History IDENTIFIERS *Hawaii; *Land Rights ABSTRACT , Volume II of the final report of theNative ftwaiians Study Commission (NHSC) on the culture,needs, and concerns of native Hawaiians, this book contains a formaldissent to the conclusions and recommendations presented in Volume I madeby three of the NBSC commissioners. Its principal criticism'is.that Volume 'I fails to address the' underlying intent of thecommissioned. study:. (1) to ssoss-the American involvementin the take-over of the Kingdom of Hawaii; (2)`based,on the findingregarding'American participation in the coup.etatWe of. 1893, to ascertainwhether American culpability 'for injuries or damages suffered. :.by Native Hawaiians existedrand (3) to advise about how toapproach. *lid answer any such.Native 'Hawaiian claims. This volume of the :eportfurther states that critical support is lacking for Volume\I'sargument that the United -

Ka Poʻe Aloha ʻāina 1894 He Moʻolelo Hoʻonaue Puʻuwai: Hawaiian Defiance a Year After the Overthrow a Thesis Submitted To

KA POʻE ALOHA ʻĀINA 1894 HE MOʻOLELO HOʻONAUE PUʻUWAI: HAWAIIAN DEFIANCE A YEAR AFTER THE OVERTHROW A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAIʻI AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN HAWAIIAN STUDIES MAY 2019 By Keanupōhina Mānoa Thesis Committee: Kamanamaikalani Beamer, Chairperson W. Kekailoa Perry Kamoaʻe Walk Abstract There were different and opposing national identities claiming to represent Hawaiʻi in 1894. A year after the illegal overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom, the same insurgents now calling themselves the Provisional Government of Hawaiʻi (PG) were putting on a one-year anniversary celebration. Depending on the newspapers and other records from the day, completely different stories could be told on this same event. The PG attempted to spread political myth as fact, to legitimize their cause, and give them the appearance of embodying American values. Opposing English language newspapers however, were able to unravel many of these political myths, thus delegitimizing the PG and highlighting President Cleveland’s rejection of annexation. Meanwhile, Hawaiian language writers, first demonstrating an intimate and expert knowledge of Hawaiʻi’s situation, then published and used this knowledge to express themselves and find answers in a very Hawaiian way – through the use of metaphor and kaona - to further delegitimize the PG. Because these writings were published and kept, these writers simultaneously preserved Hawaiian thought and action from this turbulent time for Hawaiians today. These stories can act as an example of Hawaiian identity and Hawaiian Nationalism in a time of great political change, thereby perhaps showing one way to move forward in today’s politically changing environment. -

Bibliography of Native Hawaiian Legal Resources

Bibliography of Native Hawaiian Legal Resources Materials Available at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa Libraries Center for Excellence in Native Hawaiian Law William S. Richardson School of Law University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa Lori Kidani 2007 TABLE OF CONTENTS CALL NUMBER LOCATIONS.....................................................................................................1 BIBLIOGRAPHIES......................................................................................................................2 CULTURAL KNOWLEDGE AND PROPERTY ............................................................................3 LAND AND NATURAL RESOURCES.........................................................................................5 LAWS, CURRENT ......................................................................................................................9 LAWS, HISTORICAL ................................................................................................................10 LEGAL CASES .........................................................................................................................18 NATIVE RIGHTS AND CLAIMS................................................................................................20 OVERTHROW AND ANNEXATION..........................................................................................23 REFERENCE MATERIALS.......................................................................................................26 SOVEREIGNTY AND SELF DETERMINATION........................................................................27 -

Thesis Pdf (352.6Kb)

UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN – EAU CLAIRE “LIVING ON THE CRUST OF A VOLCANO” THE OVERTHROW OF THE HAWAIIAN MONARCHY AND THE UNITED STATES’ INVOLVEMENT HISTORY 489 DR. MANN COOPERATING PROFESSOR: DR. CHAMBERLAIN BY: ALISON KELSO EAU CLAIRE, WISCONSIN MAY 13, 2008 Copyright for this work is owned by the author. This digital version is published by McIntyre Library, University of Wisconsin Eau Claire with the consent of the author. ABSTRACT The overthrow of the Hawaiian Monarchy took place on January 17, 1893. One of the debates surrounding this event is the involvement of the United States through its representative, Minister John L. Stevens. 1874-1894 was an unstable period in Hawaii. This paper discusses the reign of King Kalakaua (1874-1891), the economic relationship between Hawaii and the United States after the Reciprocity Treaty of 1876, the Revolution of 1887 that resulted in a new constitution, the overthrow of Queen Liliuokalani in 1893, and the United States investigation of the events through the Blount Report and the Morgan Report. It shows that the United States was not a conspirator in the overthrow of the Hawaiian Monarchy and that it was the result of the process of imperialism. CONTENTS ABSTRACT …………………………………………………………………………………….. ii INTRODUCTION…………………………………………………………….…………………. 1 PART I. KING KALAKAUA Constitutional Monarchy ………………...……………………..............……….………. 6 New Stirps for a Royal Family ………...………………………………..................……. 7 The Reciprocity Treaty ………….………………………………………………………. 9 Results of the Treaty ……………….…………………………………………..………. 12 The Merry Monarchy ……………………….………………………………………….. 16 Kalakaua’s Government ………………………...……………………………………… 19 The Bayonet Constitution ……………...………………...…………………………….. 23 1887-1891: An Attempted Revolution and the Death of the King ………………....….. 26 PART II. QUEEN LILIUOKALANI The King is Dead: Long Live the Queen! …………………..……………………….…. -

From Mauka to Makai

FROM MAUKA TO MAKAI: THE RIVER OF JUSTICE MUST FLOW FREELY \, . REPORT ON THE RECONCILIATION PROCESS BETWEEN THE FEDERAL GOVERNMENT AND NATIVE HAWAIIANS PREPARED BY THE DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR AND THE DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE OCTOBER 23, 2000 University of Hawaii School of Law Library - Jon Van Dyke Archives Collection --- FROM MAUKA TO MAKAI: THE RIVER OF JUSTICE MUST FLOW FREELY REPORT ON THE RECONCILIATION PROCESS BETWEEN THE FEDERAL GOVERNMENT AND NATIVE HAWAIIANS PREPARED BY THE DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR AND THE DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE OCTOBER 23, 2000 Description of the Reconciliation Process and this Report In 1993, with Public Law 103-150, the Apology Resolution, the United States apologized to the Native Hawaiian people for the overthrow of the Kingdom of Hawai' i in 1893 and expressed its commitment to acknowledge the ramifications of the overthrow in order to provide a proper foundation for reconciliation between the United States and the Native Hawaiian people. The passage of the Apology Resolution was the first step in this reconciliation process. In March of 1999, Senator Daniel K. Akaka asked Secretary of the Interior Bruce Babbitt and Attorney General Janet Reno to designate officials to represent their respective Departments in efforts of reconciliation between the Federal Government and Native Hawaiians. Secretary Babbitt designated John Berry, Assistant Secretary, Policy Management and Budget, for the Department of the Interior (Interior), and Attorney General Reno designated Mark Van Norman, Director, Office of Tribal Justice, for the Department of Justice (Justice)(together, the Departments), to commence the reconciliation process. Messrs. Berry and Van Norman, the authors of this Report, have accepted Senator Akaka's definition of "reconciliation" as a "means for healing," and in addition believe, in words taken from one statement, "a 'reconciliation' requires something more than being nice or showing respect. -

Supreme Court of the United States ______

NO. 07-1372 IN THE Supreme Court of the United States ___________________ STATE OF HAWAII, et al., Petitioners, v. OFFICE OF HAWAIIAN AFFAIRS, et al., Respondents. ____________________ On Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of Hawai‘i ____________________ BRIEF OF THE HAWAI‘I CONGRESSIONAL DELEGATION AS AMICUS CURIAE IN SUPPORT OF RESPONDENTS ____________________ SRI SRINIVASAN (Counsel of Record) KATHRYN E. TARBERT O’MELVENY & MYERS LLP 1625 Eye Street, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20006 (202) 383-5300 Attorneys for Amicus Curiae i TABLE OF CONTENTS Page BRIEF OF THE HAWAI‘I CONGRESSIONAL DELEGATION AS AMICUS CURIAE IN SUPPORT OF RESPONDENTS .............................. 1 INTEREST OF AMICUS CURIAE .......................... 1 SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT................................... 3 ARGUMENT ............................................................. 4 I. THE SUPREME COURT OF HAWAI‘I PROPERLY RELIED UPON THE APOLOGY RESO- LUTION IN APPLYING STATE LAW ..................................................... 4 A. The Apology Resolution Settles A Century Of De- bate In Both The Legisla- tive And Executive Branches Over The Legal- ity Of—And The United States’ Responsibility For—The Overthrow Of The Kingdom Of Hawai‘i .......... 5 B. The Supreme Court Of Hawai‘i Properly Relied On The Factual Findings Of The Apology Resolution In Construing The Scope Of State-Law Trust Obli- gations ..................................... 12 ii TABLE OF CONTENTS (continued) Page II. THE PROCESS OF RECON- CILIATION WITH THE NATIVE HAWAIIAN PEOPLE CONTIN- UES TO MOVE FORWARD.............. 17 CONCLUSION........................................................ 21 iii TABLE OF AUTHORITIES Page(s) CASES Han v. United States Dep’t of Justice, 45 F.3d 333 (9th Cir. 1995).................................. 7 Ishida v. United States, 59 F.3d 1224 (Fed. Cir. 1995)............................ 14 Jacobs v. -

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD—SENATE June 14, 2005

12372 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD—SENATE June 14, 2005 William Pryor’s consistent pursuit of provide more with less, and, as a re- is thus instructive to take a close look extreme and incorrect legal views sult, students of every age from head at that history. should have been a red flag for my col- start to higher education—are getting [The Grassroot Institute of Hawaii, Jun. 1, leagues. It should have demonstrated sub-par educations. 2005] how dangerous placing him on the Fed- Our Nation is now more dependent on HAWAII DIVIDED AGAINST ITSELF CANNOT eral bench with lifetime tenure would foreign oil than ever before. We rely STAND—AN ANALYSIS OF THE APOLOGY RES- be. Unfortunately, Mr. President, it did heavily on Middle East countries that OLUTION not. As a result, our Federal judiciary do not share our values—a reliance (By Bruce Fein) will have less ability to protect the that makes us more vulnerable every THE 1993 APOLOGY RESOLUTION IS RIDDLED WITH constitutional rights we hold so dear. day—yet still, Americans are suffering FALSEHOODS AND MISCHARACTERIZATIONS Thomas B. Griffith presents a similar at the pump, paying $2.12 a gallon. The Akaka Bill originated with the 1993 threat to our constitutional rights, Our military families, the people who Apology Resolution (S.J. Res. 19) which particularly to the rights of women. As are the front line in the war on terror passed Congress in 1993. Virtually every a member of the President’s Commis- and allow us to live life as we know, paragraph is false or misleading. -

Hawaiian History: the Dispossession of Native Hawaiians' Identity, and Their Struggle for Sovereignty

California State University, San Bernardino CSUSB ScholarWorks Electronic Theses, Projects, and Dissertations Office of aduateGr Studies 6-2017 Hawaiian History: The Dispossession of Native Hawaiians' Identity, and Their Struggle for Sovereignty Megan Medeiros CSUSB Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd Part of the Law Commons, Other Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons, Political Science Commons, and the Sociology Commons Recommended Citation Medeiros, Megan, "Hawaiian History: The Dispossession of Native Hawaiians' Identity, and Their Struggle for Sovereignty" (2017). Electronic Theses, Projects, and Dissertations. 557. https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd/557 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Office of aduateGr Studies at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses, Projects, and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HAWAIIAN HISTORY: THE DISPOSSESSION OF NATIVE HAWAIIANS’ IDENTITY, AND THEIR STRUGGLE FOR SOVEREIGNTY ______________________ A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino _______________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in Social Sciences and Globalization ______________________ by Megan Theresa Ualaniha’aha’a Medeiros June 2017 HAWAIIAN HISTORY: THE DISPOSSESSION OF NATIVE HAWAIIANS’ IDENTITY, AND THEIR STRUGGLE FOR SOVEREIGNTY ______________________