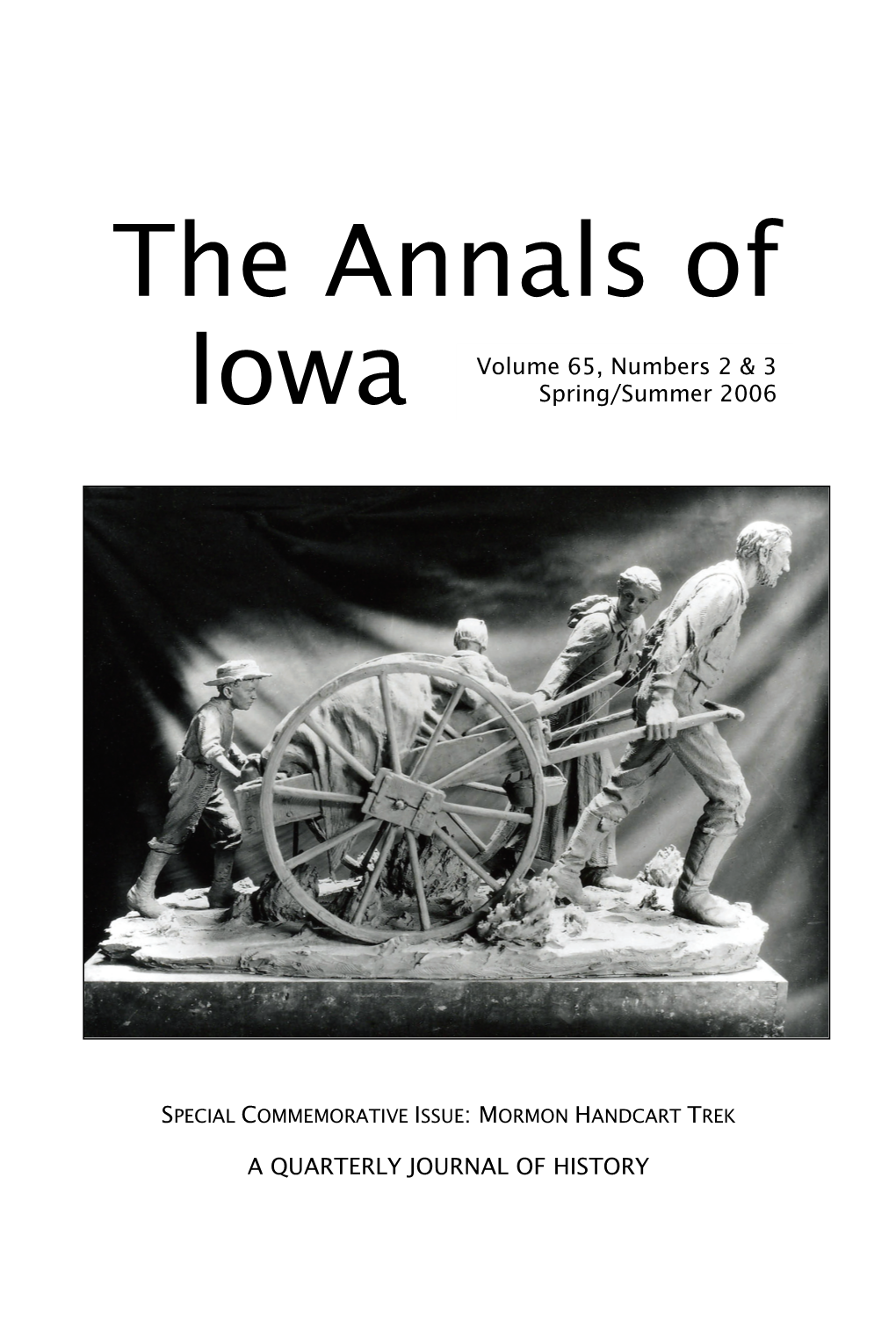

The Annals of Iowa Volume 65, Numbers 2 & 3

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MARY JANE WOODGER 275 E Joseph Smith Building Brigham Young University Provo, Utah 84602 (801) 422-9029 Work

MARY JANE WOODGER 275 E Joseph Smith Building Brigham Young University Provo, Utah 84602 (801) 422-9029 Work PROFESSIONAL TRACK 2009-present Professor of Church History and Doctrine, BYU 2003-2009 Associate Professor of Church History and Doctrine, BYU 1997-2003 Assistant Professor of Church History and Doctrine, BYU 1994-99 Faculty, Department of Ancient Scripture, BYU Salt Lake Center 1980-97 Department Chair of Home Economics, Jordan School District, Midvale Middle School, Sandy, Utah EDUCATION 1997 Ed.D. Brigham Young University, Educational Leadership, Minor: Church History and Doctrine 1992 M.Ed. Utah State University, Secondary Education, Emphasis: American History 1980 B.S. Brigham Young University, Home Economics Education HONORS 2012 The Harvey B. Black and Susan Easton Black Outstanding Publication Award: Presented in recognition of an outstanding published scholarly article or academic book in Church history, doctrine or related areas for Against the Odds: The Life of George Albert Smith (Covenant Communications, Inc., 2011). 2012 Alice Louise Reynolds Women-in-Scholarship Lecture 2006 Brigham Young University Faculty Women’s Association Teaching Award 2005 Utah State Historical Society’s Best Article Award “Non Utah Historical Quarterly,” for “David O. McKay’s Progressive Educational Ideas and Practices, 1899-1922.” 1998 Kappa Omicron Nu, Alpha Tau Chapter Award of Excellence for research on David O. McKay 1997 The Crystal Communicator Award of Excellence (An International Competition honoring excellence in print media, 2,900 entries in 1997. Two hundred recipients awarded.) Research consultant for David O. McKay: Prophet and Educator Video 1994 Midvale Middle School Applied Science Teacher of the Year 1987 Jordan School District Vocational Teacher of the Year PUBLICATIONS Authored Books (18) Casey Griffiths and Mary Jane Woodger, 50 Relics of the Restoration (Springville, Utah: Cedar Fort Press, 2020). -

A Study of Historical Evidences Related to LDS Church As Reflected in Volumes XIV Through XXVI of the Journal of Discourses

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 1976-04-01 A Study of Historical Evidences Related to LDS Church as Reflected in olumesV XIV Through XXVI of the Journal of Discourses Terry J. Aubrey Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the Cultural History Commons, and the Mormon Studies Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Aubrey, Terry J., "A Study of Historical Evidences Related to LDS Church as Reflected in olumesV XIV Through XXVI of the Journal of Discourses" (1976). Theses and Dissertations. 4490. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/4490 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. -

Overland-Cart-Catalog.Pdf

OVERLANDCARTS.COM MANUFACTURED BY GRANITE INDUSTRIES 2020 CATALOG DUMP THE WHEELBARROW DRIVE AN OVERLAND MANUFACTURED BY GRANITE INDUSTRIES PH: 877-447-2648 | GRANITEIND.COM | ARCHBOLD, OH TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents Need a reason to choose Overland? We’ll give you 10. 8 & 10 cu ft Wheelbarrows ........................ 4-5 10 cu ft Wheelbarrow with Platform .............6 1. Easy to operate – So easy to use, even a child can safely operate the cart. Plus it reduces back and muscle strain. Power Dump Wheelbarrows ........................7 4 Wheel Drive Wheelbarrows ................... 8-9 2. Made in the USA – Quality you can feel. Engineered, manufactured and assembled by Granite Industries in 9 cu ft Wagon ...............................................10 Archbold, OH. 9 cu ft Wagon with Power Dump ................11 3. All electric 24v power – Zero emissions, zero fumes, Residential Carts .................................... 12-13 environmentally friendly, and virtually no noise. Utility Wagon with Metal Hopper ...............14 4. Minimal Maintenance – No oil filters, air filters, or gas to add. Just remember to plug it in. Easy Wagons ...............................................15 5. Long Battery Life – Operate the cart 6-8 hours on a single Platform Cart ................................................16 charge. 3/4 cu yd Trash Cart .....................................17 6. Brute Strength – Load the cart with up to 750 pounds on a Trailer Dolly ..................................................17 level surface. Ride On -

(Utah). Probate Court Land Title Certificates, 1851-1895

Salt Lake County (Utah). Probate Court Land Title Certificates, 1851-1895 Series #PC-001 Processed by: Ronda Frazier Date Completed: February, 2009 Salt Lake County Records Management & Archives 4505 South 5600 West West Valley City, Utah 84120 E-mail: [email protected] Salt Lake County (Utah). Probate Court. Land Title Certificates. Series #PC-001 Overview of Records Creator: Salt Lake County Probate Court Title: Land Title Certificates Dates: 1851-1895 (bulk 1871-1873) Series Number: PC-001 Quantity: 46 boxes (45 Manu Legal, 1 Manu Half), 20.5 cubic ft. Abstract: Certificates of Land Title issued to Utah settlers, by the Probate Court of Salt Lake County, establishing legal title to their land under an Act of Congress entitled, “An Act for the relief of the Inhabitants of Cities and Towns upon the Public Lands, approved March 2, 1867.” Agency History The Probate Court was established with the creation of Utah as a territory in 1851. Federal law gave territorial probate courts the power to deal with matters of estates of deceased persons and the guardianship of the estates of minors and the incompetent. In 1852, the Territorial Legislature gave the Probate Court jurisdiction over civil, criminal, and chancery matters. The court could also act as an appellant court to the Justice of the Peace Courts within the county, and all Probate Court proceedings could be appealed to the District Court. Estate cases handled by the Court included probate and guardianship matters. These included adoptions after the legislature first made provisions for adoption as a legal process in 1884. Civil cases included primarily divorce, debt, replevin, damages, delinquent tax collections, contract and property disputes, and evictions. -

30 June, 2000 Update

6 January 2013 update 18 June 2006 update 1785 To 1888 England to Utah Timeline starts on page 3 akrc PC:Word:RowWmTmLn april coleman, 2608 E Camino, Mesa, AZ 85213 (602)834-3209 email [email protected] “The exodus would ever be more trial than trail.” “Come, calm or strife, turmoil or peace, life or death, in the name of Israel’ s God we mean to conquer or die trying.” Pres. Brigham Young, as quoted by, Richard E Bennett, “Winter Quarters,” Ensign, 40-53 “In all its history, the American West never saw a more unlikely band of pioneers than the four hundred-odd who were camped on the bank of the Iowa River at Iowa City in early June, 1856. There were more women than men, more children under fifteen than either. One in every ten was past fifty, the oldest a woman of seventy-eight; there were widows and widowers with six or seven children. Most of them, until they were herded from their crowded immigrant ship and loaded into the cars and rushed to the end of the Rock Island Line and dumped on the brink of the West, had never pitched a tent, slept on the ground, cooked outdoors, built a campfire. They had not even the rudimentary skills that make frontiersmen. But it turned out, that they had the stuff that makes heroes”. Wallace Stegner, The Gathering of Zion SARAH ANN, ELIZA, ABIGAIL, SUZANNE Pioneer Sesquicentennial Project - akrc March 1997 SARAH ANN, ELIZA, ABIGAIL, SUZANNE, What did you leave when you left your home land? When you followed a husband, who followed his God? Would you have come, if you had known the path your feet would trod? Suzanne back in France so long ago, across waters, wide and deep, That long trip to New York, And a language you couldn't speak. -

A Brief History of the Scandinavian Mission by Andrew Jensen

A Brief History of the Scandinavian Mission Andrew Jenson, Encyclopedic History of the Church of Jesus Christ of latter-Day Saints p.779- 780 SCANDINAVIAN MISSION (The) embraced the three Scandinavian countries, Denmark, Sweden and Norway, and at different times also Iceland and Finland. The headquarters of the mission were at Copenhagen, Denmark. The population of Denmark is about 3,000,000, Sweden about 6,140,000, and Norway about 2,890,000 [in about 1940]. The preaching of the restored gospel was confined to the English-speaking people (Indians excepted) until 1843, when the first missionaries were sent to the Pacific Islands, where they founded the Society Islands Mission in 1844; but after the headquarters of the Church had been established in Great Salt Lake Valley and the first missionaries were called from there to foreign lands, missionaries were chosen to open up the door for the restored gospel in France, Germany, Italy, and Scandinavia, on the continent of Europe. Thus Apostle Erastus Snow was called to open up a mission in the Scandinavian countries, and with him Peter O. Hansen was called specially to Denmark, and John E. Forsgren to Sweden. These brethren left Great Salt Lake Valley, together with other missionaries, in October, 1849, and arrived in Great Britain early the following year. Erastus Snow, while stopping in England, chose George Parker Dykes, who was laboring as a missionary in England, to accompany him and the other brethren mentioned to Scandinavia. Elders Snow, Forsgren and Dykes arrived in Copenhagen, Denmark, June 14, 1850, (having been preceded there by a month or so by Peter O. -

The Development of Municipal Government in the Territory of Utah

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 1972 The Development of Municipal Government in the Territory of Utah Alvin Charles Koritz Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the Mormon Studies Commons, and the Political Science Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Koritz, Alvin Charles, "The Development of Municipal Government in the Territory of Utah" (1972). Theses and Dissertations. 4856. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/4856 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive All Theses and Dissertations 1972 The evelopmeD nt of Municipal Government in the Territory of Utah Alvin Charles Koritz Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the Mormon Studies Commons, and the Political Science Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Koritz, Alvin Charles, "The eD velopment of Municipal Government in the Territory of Utah" (1972). All Theses and Dissertations. 4856. http://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/4856 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE DEVELOPMENT OF MUNICIPAL GOVERNMENT IN THE TERRITORY OF UTAH A Thesis Presented to the Department of Political Science Brigham Young University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts by Alvin Charles Koritz August 1972 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The author sincerely wishes to acknowledge the assistance and encouragement given to him by the following people: Dr. -

Perspectives on the Restored Gospel

Religious Educator: Perspectives on the Restored Gospel Volume 13 Number 3 Article 14 9-2012 Full Issue Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/re BYU ScholarsArchive Citation "Full Issue." Religious Educator: Perspectives on the Restored Gospel 13, no. 3 (2012). https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/re/vol13/iss3/14 This Full Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Religious Educator: Perspectives on the Restored Gospel by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. TH E R EL i vol. 13 no. 3 · 2012 G iou S A Century of Seminary E D u Sacred Learning cat o Breathing Life into a Dead Class R perspectives oN THE rest oRED GoSPEL InsIde ThIs Issue: • P erspect How to Survive in Enemy Territory President Boyd K. Packer i ves A Century of Seminary o N Casey Paul Griffiths THE Sacred Learning R est Elder Kevin J Worthen o RED Teaching the Four Gospels: Five Considerations Gaye Strathearn Go SPEL Jesus Christ and the Feast of Tabernacles Ryan S. Gardner RELIGIOUS STUDIES CENTER • BRIGHAM YOUNG UNIVERSITY The Savior’s Teachings on Discipleship during His Final Trek to Jerusalem Casey W. Olson Paul and James on Faith and Works Mark D. Ellison Belief in a Promise: The Power of Faith Jeffrey W. Carter Religious Educator Articles Related to the New Testament Terry F. Calton Breathing Life into a Dead Class Lloyd D. Newell Covenants, Sacraments, and Vows: The Active Pathway to Mercy Peter B. -

Lessons in Genealogy

— — =f=== a? ^ LESSONS IN GENEALOGY PUBLISHED BY THE GENEALOGICAL BOCIETY OF UTAH SALT LAKE CITY, UTAH 1915 ^ A Daughter of the North Nephi Anderson's splendid new story,—interest- ing, instructive, full of the gospel spirit. It is recom- mended for young and old. Beautifully printed and bound. Sent prepaid by the author, 60 East South Temple Street, Salt Lake City, Utah; price, 75 cents. OTHER BOOKS BY NEPHI ANDERSON "Added Upon", "The Castle Builder", "Piney Ridge Cottage", "Story of Chester Lawrence", 75 cents each by all booksellers, or by the author. John Stevens' Courtship BY SUSA YOUNG GATES A love story of the Echo Canyon War Times PRICE - $1.00 On sale by all Booksellers and by the Author Room 28, Bishop's Building, Salt Lake City, Utah LESSONS IN GENEALOGY PUBLISHED BY THE GENEALOGICAL SOCIETY OF UTAH THIRD EDITION SALT LAKE CITY, UTAH 1915 The Genealogical Society of Utah Organized November 13, 1894 ANTHON H. LUND, President CHARLES W. PENROSE, Vice President JOSEPH F. SMITH, JR., Secretary and Treasurer NEPHI ANDERSON, Assistant Secretary JOSEPH CHRISTENSON, Librarian LILLIAN CAMERON, Assistant Librarian DIRECTORS: Anthon H. Lund, Charles W. Penrose, Joseph Christenson, Joseph F. Smith, Jr., Anthony W. Ivins, Duncan M. McAllister, Heber J. Grant. Life Membership, $10, with two years in which to pay Annual Membership, $2 the first year, $1 yearly thereafter The Utah Genealogical and Historical Magazine Published by the Genealogical Society of Utah Quarterly, $1.50 per Annum Anthon H. Lund, Editor Nephi Anderson, Associate Editor Subscription price to life and paid-up annual members of the Gen- ealogical Society, $1.00 a year. -

George Became a Member of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints As a Young Man, and Moved to Nauvoo, Illinois

George became a member of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints as a young man, and moved to Nauvoo, Illinois. Here he met and married Thomazine Downing on August 14, 1842. George was a bricklayer, so he was busy building homes in Nauvoo and helping on the temple. When the Saints were driven out of Nauvoo in 1846, George and Thomazine moved to Winter Quarters. Here George, age 29, was asked to be a member of Brigham Young’s Vanguard Company headed to the Salt Lake Valley. They made it to the Valley on July 24, 1847. While George was gone from Winter Quarters, his brother, William Woodward, died in November 1846 at Winter Quarters. He was 37 years of age. In August 1847, George headed back to Winter Quarters, but on the way met his wife coming in the Daniel Spencer/Perrigrine Sessions Company, so he turned around and returned to the Salt Lake Valley with his wife. They arrived back in the Valley the end of September 1847. There are no children listed for George and Thomazine. In March 1857, George married Mary Ann Wallace in Salt Lake City. Mary Ann had immigrate to the Valley with her father, Neversen Grant Wallace, in the Abraham O. Smoot Company. There is one daughter listed for them, but she died at age one, in August 1872, after they had moved to St. George, Utah. George moved to St. George in the summer of 1872. For the next several years, George was busy establishing his home there and helping this community to grow. -

Downloads/Jesuit Arabic Bible.Pdf 27 King James Version (KJV)

1 ©All rights reserved 2 Introduction Irenaeus, Polycarp, Papias New Testament Canonicity The Ten Papyri from the second century There is no co-called the original Gospel of the Four Gospels Anonymous Epistles within the New Testament A quick tour in the history of the New Testament The Gospel of John and the Greek Philosophy Were the scribes of the four Gospels, disciples of Jesus Christ? Who wrote the Gospel according to Matthew’s account? Who wrote the Gospel according to John’s account? Did the Holy Spirit inspire the four Gospels? Confessions of the Gospel of Luke The Church admits that there are forged additions in the New Testament The Gospel of Jesus Christ Who wrote the Old Testament? Loss of the Torah (Old Testament) Loss of a large number of the Bible's Books 3 In my early twenties, I have started my journey of exploring the world. I have visited many countries around the world and learnt about many different cultures and customs. I was shocked by the extent difference between the religions. I saw the Buddhist monks distancing themselves from the worldly life and devoting themselves to worshipping their god, Buddha. I saw the Christian monks isolating themselves in the monasteries and devoting themselves to worshipping their god, Jesus Christ. I saw those who worship trees, stones, cows, mice, fire, money and other inanimate objects, and I saw those who do not believe in the existence of God or they do believe in the existence of God, but they say, “We do not know anything about him.” I liked to hear from each one his point of view about what he worships. -

Worth Their Salt, Too

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by DigitalCommons@USU Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All USU Press Publications USU Press 2000 Worth Their Salt, Too Colleen Whitley Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/usupress_pubs Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Whitley, C. (2000). Worth their salt, too: More notable but often unnoted women of Utah. Logan: Utah State University Press. This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the USU Press at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All USU Press Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Worth Their Salt, Too More Notable but Often Unnoted Women of Utah WORTH THEIR SALT, TOO More Notable but Often Unnoted Women of Utah Edited by Colleen Whitley UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY PRESS Logan, Utah 2000 Copyright © 2000 Utah State University Press “Marion Davis Clegg: The Lady of the Lakes” copyright © 2000 Carol C. Johnson All rights reserved Utah State University Press Logan, Utah 84322-7800 All royalties from the sale of this book will be donated to support the Exhibits office of the Utah State Historical Society. Cover photos: Marion Davis Clegg, courtesy of Photosynthesis; Verla Gean FarmanFarmaian, courtesy of Gean FarmanFarmaian; Ora Bailey Harding, courtesy of Lurean S. Harding; Alberta Henry, courtesy of the Deseret News; Esther Peterson, courtesy of Paul A. Allred; Virginia Sorensen, courtesy of Mary Bradford Typography by WolfPack Printed in Canada Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Worth their salt, too : more notable but often unnoted women of Utah / edited by Colleen Whitley.