Alekhine on Carlsbad, 1929 Edward Winter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Semmering 1926 & 1937 Extract and Extended Reprint of the Great Original by Jan Van Reek

HEALTH RESORTS: Semmering 1926 & 1937 Extract and extended reprint of the great original by Jan van Reek, www.endgame.nl SEMMERING 1926 The southern road from Wien leads to the Semmering Pass. The Grand Hotel Panhans was built at the Semmering in 1888. This facility was used for a tournament of eighteen masters from 7 until 29 iii 1926. Spielmann’s name stood not on the first list of Bernstein! Later he was invited. Nimzowitsch and Tartakower led at first. Spielmann and Alekhine competed for the first prize then. Finally, Rudolf Spielman surprisingly won, ahead of Alekhine on second place. Vidmar sr. was sole third, followed by Nimzowitsch and Tartakower as fourth, Rubinstein and Tarrasch as sixth, in total 18 players contested: http://www.chessgames.com/perl/chesscollection?cid=1013596 (Chessgames) Grand Hotel Panhans at the Semmering Casino of Baden bei Wien in modern times SEMMERING / BADEN bei Wien 1937 Casinos had to spend a part of their income on cultural aims. And a chess tournament is relatively cheap and deluxe promotion. That was the base for many chess events in casinos. When Austrian casinos organised a grandmaster contest in 1937, chaos ruled. Some men got phony invitations at first. Only Capablanca was treated with respect. Matters were sorted out, before the tournament was played from 8 until 27 ix 1937. Eight excellent masters carried out double rounds. World champion Euwe was chief arbiter. When he left, Spielmann replaced him. The first four rounds were conducted at the Grand Hotel Panhans in Semmering, and then moved to the Hotel Grüner Baum in Baden bei Wien, Austria for the duration of the tournament. -

![The Art of Sacrifice in Chess (Dover Chess) by Rudolf Spielmann [Book]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5763/the-art-of-sacrifice-in-chess-dover-chess-by-rudolf-spielmann-book-1565763.webp)

The Art of Sacrifice in Chess (Dover Chess) by Rudolf Spielmann [Book]

The Art of Sacrifice in Chess (Dover Chess) by Rudolf Spielmann ebook Ebook The Art of Sacrifice in Chess (Dover Chess) currently available for review only, if you need complete ebook The Art of Sacrifice in Chess (Dover Chess) please fill out registration form to access in our databases Download here >> Series:::: Dover Chess+++Paperback:::: 224 pages+++Publisher:::: Dover Publications; Reissue edition (November 2, 2011)+++Language:::: English+++ISBN-10:::: 0486284492+++ISBN-13:::: 978-0486284491+++Product Dimensions::::5.5 x 0.8 x 8.8 inches++++++ ISBN10 0486284492 ISBN13 978-0486284 Download here >> Description: The beauty of a game of chess is usually appraised, and with good reason, according to the sacrifices it contains. On principle we incline to rate a sacrificial game more highly than a positional game. Instinctively we place the moral value above the scientific. We honor Capablanca, but our hearts beat higher when Morphy’s name is mentioned. — Introduction.Perhaps the strongest Austrian-born grandmaster of the20th century, Rudolf Spielmann (1883–1942) defeated such world-class opponents as Nimzovich, Tartakower, Bogoljubov — and even the great Capablanca. Among the reasons for his success was his mastery of the art of sacrifice. In this ground-breaking classic, distilled from 40 years of tournament play, he outlines the hard-won lessons that enable a player to win games by giving up pieces!Drawing on dozens of his own games against such topflight players as Schlechter, Tartakower, Bogoljubov, Reti, Rubinstein and Tarrasch, Spielmann describes and analysis various type of sacrifices: (positional, for gain, mating) and real sacrifices: (for development, obstructive, preventive, line-clearance, vacating, deflecting and more). -

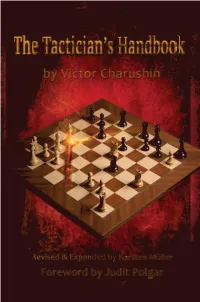

The Tactician's Handbook

The Tactician’s Handbook by Viktor Charushin Revised and Expanded by Karsten Müller Foreword by Judit Polgar 2016 Russell Enterprises, Inc. Milford, CT USA 1 The Tactician’s Handbook by Viktor Charushin Revised and Expanded by Karsten Müller ISBN: 978-1-941270-34-9 (print) ISBN: 978-1-941270-35-6 (print) © Copyright 2016 Karsten Müller All Rights Reserved No part of this book may be used, reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any manner or form whatsoever or by any means, electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the express written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. Published by: Russell Enterprises, Inc. P.O. Box 3131 Milford, CT 06460 USA http://www.russell-enterprises.com [email protected] Cover design by Janel Norris Editing and proofreading by Peter Kurzdorfer Printed in the United States of America Table of Contents Preface by Karsten Müller 4 Signs & Symbols 5 Foreword by Judit Polgar 6 Alekhine’s Block 8 Alekhine’s Block: Exercises 51 Alekhine’s Block: Solutions 56 Combination Cross 61 Combination Cross: Exercises 89 Combination Cross: Solutions: 93 Domination 97 Domination: Exercises 127 Domination: Solutions 131 Lasker’s Combination 133 Lasker’s Combination: Exercises 158 Lasker’s Combination: Solutions 164 Mitrofanov’s Deflection 170 Mitrofanov’s Deflection: Exercises 189 Mitrofanov’s Deflection: Solutions 191 The Steeplechase 193 The Steeplechase: Exercises 212 The Steeplechase: Solutions 214 Less Common Combinations 215 Less Common Combinations: Exercises 235 Less Common Combinations: Solutions 239 3 The Tactician’s Handbook Preface After I had finished work on the new edition of Rudolf Spielmann’s classic The Art of Sacrifice, publisher Russell Enterprises approached me with the idea of publishing a new edition of Charushin’s seven books on tactics. -

ECU E-Magazine December 2020

E-MAGAZINE DECEMBER 2020 0101 Women's Club Cup Cercle d'Echecs de Monte- Carlo wins European Online Women's Club Cup! ECU General Assembly ECU Annual Meeting took place on 19.12.2020 GM JONES GAWAIN WINS EUROPEAN ONLINE BLITZ CHESS CHAMPIONSHIP! 2021, new Year, new Challenges... ECU Board & Officers wishing you and yours a safe, healthy, and prosperous new year! The Annual ECU General Assembly took place online on Saturday 19th of December 2020 with the presence of 40 National Federations. European Blitz #Chess Championship and European Womne's Club Cup were organised succefully online. Full reports. European Chess Union has its seat in Switzerland, European Chess Union and ECU Arbiters Council Address: Rainweidstrasse 2, CH-6333, Hunenberg See, Switzerland launche the special courses for Chess Arbiters Online European Chess Union is an independent association founded in 1985 in Graz, Austria; European Chess Union has 54 National Federation 8th London Chess Conference – ChessTech2020 took Members; Every year ECU organizes more than 20 prestigious events and championships. place online this year, on 5th and 6th December 2020. www.europechess.org [email protected] contents ECU Online Blitz Championship ECU General Assembly ECU102 course report 03 GM Jones Gawain wins European 08 Communique of the ECU 16 Online Blitz Chess Championship Annual General Assembly ECU FIDE Arbiters seminar 2020 for female participants Women's Club Cup ECU Federation news Arbiters Corner 05 Cercle d'Echecs de Monte-Carlo 10 100 years anniversaries -

Chess Autographs

Chess Autographs Welcome! My name is Gerhard Radosztics, I am living in Austria and I am a chess collector for many years. In the beginning I collected all stuff related to chess, especially stamps, first day covers, postmarks, postcards, phonecards, posters and autographs. In the last years I have specialised in Navigation Autograph Book Old chess postcards (click on card) A - M N - Z Single Chess autographs Links Contact On the next pages you can see a small part of my collection of autographs. The most of them are recognized, if you can recognize one of the unknown, please feel free to e-mail me. Note: The pages are very graphic intensive, so I ask for a little patience while loading. http://www.evrado.com/chess/autogramme/index.shtml[5/26/2010 6:13:18 PM] Autograph Book Autograph Book pages » back to previous page Page 1 - Introduction Page 18 - Marshall Page 2 - Aljechin Page 19 - Spielmann Page 3 - Lasker Page 19a - Capablanca Page 4 - Gruenfeld Page 20 - Canal Page 5 - Rubinstein Page 21 - Prokes Page 6 - Monticelli Page 22 - Euwe Page 7 - Mattisons Page 23 - Vidmar Page 8 - Asztalos Page 24 - Budapest 1948 Page 9 - Kmoch Page 25 - HUN - NED 1949 Page 10 - Gilg Page 25a - HUN - YUG 1949 Page 11 - Tartakover Page 26 - Budapest 1959 Page 12 - Nimzowitsch Page 26a - Budapest 1959 Page 13 - Colle Page 27 - Olympiad Leipzig Page 14 - Brinckmann Page 28 - Olympiad Leipzig Page 15 - Yates Page 29 - Budapest 1961 Page 16 - Kagan Page 30 - Spart.-Solingen 76 Page 17 - Maroczy http://www.evrado.com/chess/autogramme/autographindex.htm[5/26/2010 6:13:20 PM] Autogramme - Turniere - Namen Tournaments: » back to previous page 1 Sliac 1932 8 Dubrovnik 1950 15 Nizza 1974 2 Podebrady 1936 9 Belgrad 1954 16 Biel 1977 3 Semmering - Baden 1937 10 Zinnowitz 1967 17 Moskau 1994 4 Chotzen 1942 11 Polanica Zdroj 1967 18 Single autographs 5 Prag 1942 - Duras Memorial 12 Lugano 1968 19 World Champions Corr. -

Karlsbad Series

Karlsbad series Extended reprint from the great original HEALTH RESORTS by Jan van Reek (1945 - 2015), www.endgame.nl (inactive). There were four famous Carlsbad chess tournaments, in 1907, 1911, 1923, and 1929, under the excellent supervision of Viktor Tietz, Senior Tax Inspector and President of the Carlsbad chess organization. Viktor Tietz (Photo: Wikipedia) Prior, Karlsbad already hosted a match between Albin and Marco in 1901 (full story: http://www.chessgames.com/perl/chess.pl?tid=88083), and another match between Janowski and Schlechter in 1902. The same year, in 1902, Viktor Tietz himself won a Triangular above 2. David Janowski, and 3. Moritz Porges, played in Karlsbad. Karlsbad (Carlsbad), today Karlovy Vary, is a famous central-European spa and resort. It was part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire until 1918, then part of Czechoslovakia, today: Czech Republic respectively, and called Karlovy Vary. Karlovy Vary or Carlsbad (Czech pronunciation: [ˈkarlovɪ ˈvarɪ] ( listen); German: Karlsbad; Karlsbad) is a spa town situated in western Bohemia, Czech Republic, on the קרלסבאד :Yiddish approximately 130 km (81 miles) west of Prague (Praha), near the German-Czech border. It is named after Charles IV, Holy Roman Emperor and King of Bohemia, who founded the city in 1370. It is historically famous for its hot springs (13 main springs, about 300 smaller springs, and the warm-water Teplá River), and the most visited spa town in the Czech Republic. (Wikipedia) Survey: The winners of the international invitation chess tournaments in Karlsbad (Viktor Tietz series) Karlsbad 1907 Akiba Rubinstein (Poland), 2. Maróczy, 3. Saladin, 21 players Karlsbad 1911 Richard Teichmann (Germany), 2./3. -

Metropolitan Chess Club Library DEVELOPMENT

Metropolitan Chess Club Library DEVELOPMENT ID Shelf Title Author Brief Description No. No. 1 1.1 Chess Made Easy C.J.S. Purdy & G. Aimed for beginners,1942, 64 pages. Koshnitsky 2 1.2 The Game of Chess H.Golombek Advance from beginner,1945, 255pages 3 1.3 A Guide to Chess Ed.Gerard & C. Advance from beginner 1969, 156 pages. Verviers 4 1.4 My System Aron Nimzovich Theory of chess to improve yourself 1973, 372 pages 5 1.5 Pawn Power in Chess Hans Kmoch Chess strategy using pawns.1969, 300 pages 6 1.6 The Most Instructive Games Irving Chernev 62 annotated masterpieces of modern chess of Chess Ever Played strategy. 1972, 277 pages 7 1.7 The Development of Chess Dr. M. Euwe Annotated games explaining positional play, Style combination & analysis. 1968, 152pgs 8 1.8 Three Steps to Chess A.S. Suetin Examples of modern Grandmaster play to Mastery improve your playing strength. 1982, 188pgs 9 1.9 Grandmasters of Chess Harold C. Schonberg A history of modern chess through the lives of these great players. 1973, 302 pages 10 1.10 Grandmaster Preparation L. Polugayevsky How to prepare technically and psychologically for decisive encounters where everything is at stake. 1981, 232 pages 11 1.11 Grandmaster Performance L. Polugayevsky 64 games selected to give a clear impression of how victory is gained. 1984, 174 pages 12 1.12 Learn from the GrandmastersRaymond D. Keene A wide spectrum of games by a no. of players annotated from different angles. 1975, 120 pgs 13 1.13 The Modern Chess Sacrifice Leonid Shamkovich 'A thousand paths lead to delusion, but only one to the truth.' 1980, 214 pages 14 1.14 Blunders & Brilliancies Ian Mullen and Moe Over 250 excellent exercises to asses your Moss aptitude for brilliancy and blunder. -

The Lasker Method to Improve in Chess

Gerard Welling and Steve Giddins The Lasker Method to Improve in Chess A Manual for Modern-Day Club Players New In Chess 2021 Contents Explanation of symbols...........................................6 Introduction....................................................7 Chapter 1 General chess philosophy and common sense.........11 Chapter 2 Chess strategy and the principles of positional play....14 Chapter 3 Endgame play .....................................19 Chapter 4 Attack ............................................36 Chapter 5 Defence...........................................58 Chapter 6 Knights versus bishops .............................71 Chapter 7 Amorphous positions ..............................75 Chapter 8 An approach to the openings....................... 90 Chapter 9 Games for study and analysis.......................128 Chapter 11 Combinations and tactics ..........................199 Chapter 12 Solutions.........................................215 Index of openings .............................................233 Index of names ............................................... 234 Bibliography ..................................................238 5 Introduction The game of chess is in a constant state of flux, and already has been for a long time. Several books have been written about the advances made in chess, about Wilhelm Steinitz, who is traditionally regarded as having laid the foundation of positional play (although Willy Hendriks expresses his doubts about this in his latest revolutionary book On the Origin of good -

Chess Review I

1945 MANI-IATTAN CI-IAMPIONS Albert S. Pink" •. 1945 Manh;ilUan Club Champion, peses under p aint _ ing of famous elub member Jose R. Capablanca. • , 35 CENTS • Subscription Rate ONE YEAR $3 READERS', CHESS Readers are Invited to use these columns fol' their comments on matters ot Interest REVIEW FORUM to chessplayers, COHERENCE Vol. 13, No.2 February, 1945 MARSHALL ISS UE Chess Briefs, FebrUlU'Y, 19H , $II's: )'OU say that he won the title Sirs: from S howalter In 1894 , In 1895 INDEX I ha\'e just received your I have heen I'eadl ng "Let's Frank lIlarshall memOl'ial copy Pills bury challenged him, but Play Chess" now for something FEATURES nnd a m delighted that my most he decli ned ,and retired in 1896, over a week. i am ,'ery en· Young_Eyed Che rubini of absol'bi ng hobby should have a Did $ ltowaltel' win the title thuslastic. Since I am IIOt read Chess _____________________ 3 magazine so thoroughly consist· again after that? I wish you Il y prone to enthusiasm, I think would clear this UII, Ale k h i rH~ Defends Wartime ent In Its excellence, copy by this says a lot fo r youI' effort. WILLARD HA NSEN, J r, Conduct _________________ _ 7 copy. It Is a genuine thrill that I am not exactly a beginner Games f rom Recen t Events __21 I I'e celve each month about this Jackson Heights, N, y , at chess. I have beezl playIng li llie, YOII have my vety best • Hodges became U, S, cham· rO!· several years llow--or per SERIALS wishes for YOUl' continued suc pion In 1894 by defeating Sho haps it wouh1 be DJOI'C literal to Great Masterpiece. -

Vassilis Aristotelous Chess Lessons © 2018 3 Contents

VASSILIS ARISTOTELOUS CHESS LESSONS © 2018 3 CONTENTS THE STAGES OF THE GAME ........................................................................14 The opening .......................................................................................................14 Control the centre ...............................................................................................14 Alekhine-Zubarev, Moscow 1915 ......................................................................15 Alexander Alekhine ...........................................................................................15 Develop pieces ...................................................................................................16 Shelter the King by castling ...............................................................................16 The middlegame .................................................................................................16 The endgame ......................................................................................................16 King Activation ..................................................................................................17 Passed Pawns and Promotion.............................................................................17 Chess Endgame Strategy ....................................................................................17 Top ten principles ...............................................................................................17 Common Chess Endgames ................................................................................18 -

2 Summary by Michael Negele: Our Friendly Member from Brno, Jan Kalendovský, Was Not Able to Attend Our Meeting in Vienna. Howe

Summary by Michael Negele: Our friendly member from Brno, Jan Kalendovský, was not able to attend our meeting in Vienna. However, he contributed this nice historical article about a living chess demonstration at the Vienna horse race track in the afternoon June 6th, 1928. The actors on the 64 squares of a giant chess board wore historical costumes of the second Turk siege (1683) resp. the Thirty Years´ War. The chessmasters themselves took the role of Duke Starhemberg (army commander of Vienna) = Rudolf Spielmann against Kara Mustafa Pascha = Sandor Takács. In the second game Wallenstein, Duke of Friedland = Bernhard Lichtenstein played against King Gustav Adolf of Sweden = Ernst Grünfeld. Both games ended in a draw, but the more than 2000 spectators were delighted by the colourful scenery and the music. Vienna ± Living Chess 1928 ± Wien Lebendes Schach 1928 Das Bild des Wiener Trabrennplatzes am Nachmittag des 6. Juni unterschied sich eigenartig vom gewohnten Anblick. Auf vierundsechzig weiß-schwarzen Feldern eines riesigen Schachbrettes traten die prächtigsten, längst versunkenen Gestalten der altösterreichischen Geschichte zu neuerlichem Kampfe an, diesmal aber ein unblutiger Streit in Form zweier lebender Schachpartien. Da kommandierte Graf Starhemberg seine tapferen Wiener aus der Zeit der zweiten Türkenbelagerung gegen die wilden Scharen Kara Mustaphas, dort fand der Dreißigjährige Krieg noch ein einstündiges Nachspiel, weil Wallenstein, Herzog von Friedland, mit dem Schwedenkönig Gustav Adolf nochmals die Klinge kreuzen wollte. (Wiener Bilder 17.06.1928; ein weiteres Bild findet sich in der WSZ 1928, S. 168) 2 Durch diesen ausgezeichneten Gedanken einer lebenden Schachpartie mit historischen Kostümen wurde der Schachkampf auch für solche Leute interessant, die es ansonsten nicht zu würdigen wissen, wenn die Schachmeister Takács (Kara Mustapha) und Spielmann (Graf Starhemberg), ferner Grünfeld (Gustav Adolf) und Lichtenstein (Wallenstein) zusammentreffen. -

The Art of Sacrifice in Chess (Dover Chess) Online

BKvUb [Read free] The Art of Sacrifice in Chess (Dover Chess) Online [BKvUb.ebook] The Art of Sacrifice in Chess (Dover Chess) Pdf Free Rudolf Spielmann *Download PDF | ePub | DOC | audiobook | ebooks Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook #976885 in eBooks 2012-03-08 2012-03-08File Name: B00A73IXE0 | File size: 42.Mb Rudolf Spielmann : The Art of Sacrifice in Chess (Dover Chess) before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised The Art of Sacrifice in Chess (Dover Chess): 3 of 3 people found the following review helpful. Great Classic- An art taught by an expert...By WebheadThis classic is something every chess player should read at least once. Spielmann, a great attacker and sacrificial player, shows you the thoughts, ideas, and methods of sacrifice. It's amazing how he was seemingly on the lookout for sacs at all times whether for positional or attacking gains. Great read.1 of 1 people found the following review helpful. ... the Rudolph Spielmann book on sacrifices in chess is excellent. Chess algebraic notation and added games makes the ...By A thoughtful readerThis updated version of the Rudolph Spielmann book on sacrifices in chess is excellent. Chess algebraic notation and added games makes the purchase worthwhile.0 of 0 people found the following review helpful. Definitely for the player who is playing it too close ...By Eric D. ShoemakerDefinitely for the player who is playing it too close to the vest, if you can't sacrifice, you already limit yourself to a certain level.