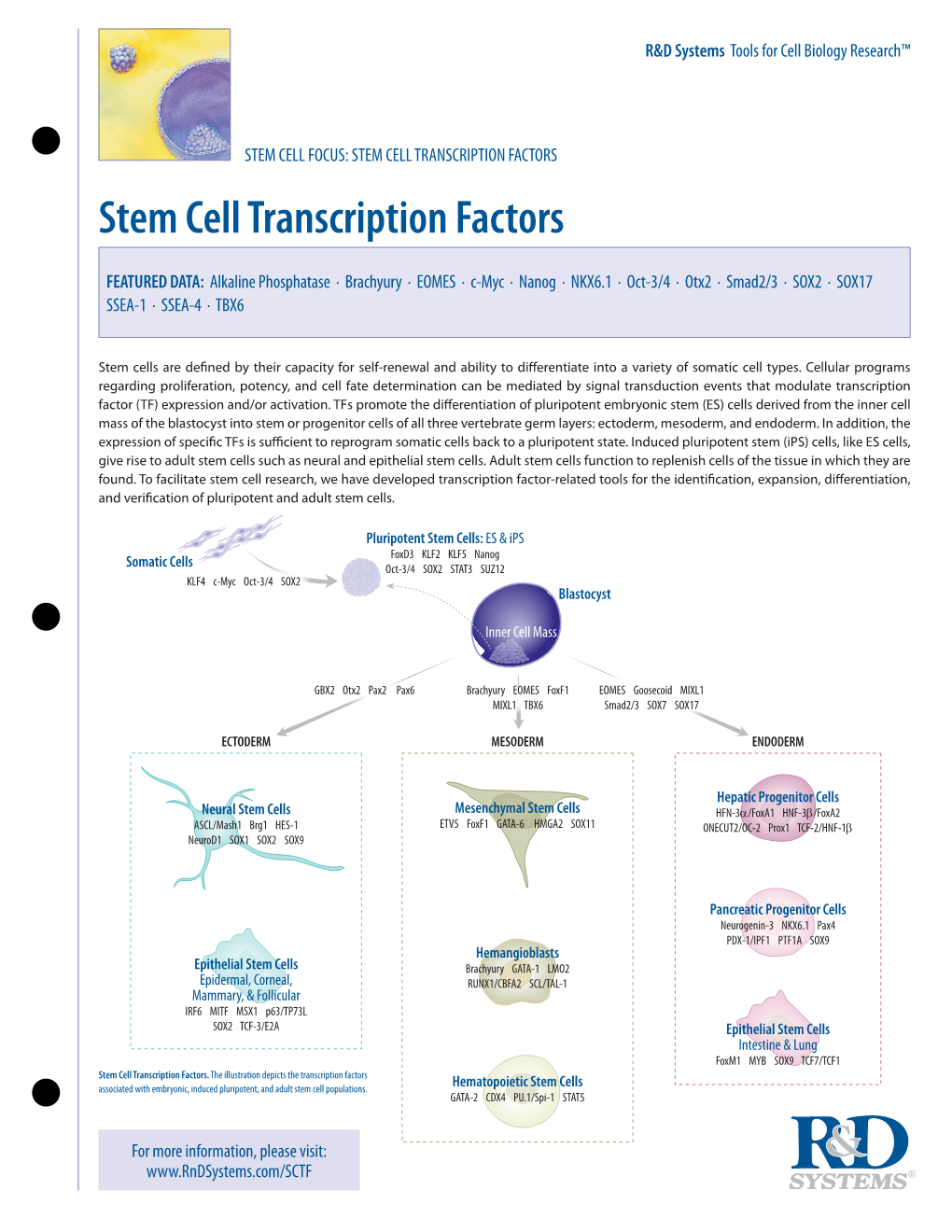

STEM CELL TRANSCRIPTION FACTORS Stem Cell Transcription Factors

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CDX4 Regulates the Progression of Neural Maturation in the Spinal Cord

Developmental Biology 449 (2019) 132–142 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Developmental Biology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/developmentalbiology CDX4 regulates the progression of neural maturation in the spinal cord Piyush Joshi a,b, Andrew J. Darr c, Isaac Skromne a,d,* a Department of Biology, University of Miami, 1301 Memorial Drive, Coral Gables, Florida, 33146, United States b Cancer and Blood Disorders Institute, Johns Hopkins All Children's Hospital, 600 5th St S, St. Petersburg, FL 33701, United States c Department of Health Sciences Education, University of Illinois College of Medicine, 1 Illini Drive, Peoria, IL 61605, United States d Department of Biology, University of Richmond, 138 UR Drive B322, Richmond, VA, 23173, United States ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: The progression of cells down different lineage pathways is a collaborative effort between networks of extra- CDX cellular signals and intracellular transcription factors. In the vertebrate spinal cord, FGF, Wnt and Retinoic Acid Neurogenesis signaling pathways regulate the progressive caudal-to-rostral maturation of neural progenitors by regulating a Spinal cord poorly understood gene regulatory network of transcription factors. We have mapped out this gene regulatory Gene regulatory network network in the chicken pre-neural tube, identifying CDX4 as a dual-function core component that simultaneously regulates gradual loss of cell potency and acquisition of differentiation states: in a caudal-to-rostral direction, CDX4 represses the early neural differentiation marker Nkx1.2 and promotes the late neural differentiation marker Pax6. Significantly, CDX4 prevents premature PAX6-dependent neural differentiation by blocking Ngn2 activation. This regulation of CDX4 over Pax6 is restricted to the rostral pre-neural tube by Retinoic Acid signaling. -

Ncomms2254.Pdf

ARTICLE Received 3 May 2012 | Accepted 5 Nov 2012 | Published 4 Dec 2012 DOI: 10.1038/ncomms2254 The RB family is required for the self-renewal and survival of human embryonic stem cells Jamie F. Conklin1,2,3, Julie Baker2,3 & Julien Sage1,2,3 The mechanisms ensuring the long-term self-renewal of human embryonic stem cells are still only partly understood, limiting their use in cellular therapies. Here we found that increased activity of the RB cell cycle inhibitor in human embryonic stem cells induces cell cycle arrest, differentiation and cell death. Conversely, inactivation of the entire RB family (RB, p107 and p130) in human embryonic stem cells triggers G2/M arrest and cell death through functional activation of the p53 pathway and the cell cycle inhibitor p21. Differences in E2F target gene activation upon loss of RB family function between human embryonic stem cells, mouse embryonic stem cells and human fibroblasts underscore key differences in the cell cycle regulatory networks of human embryonic stem cells. Finally, loss of RB family function pro- motes genomic instability in both human and mouse embryonic stem cells, uncoupling cell cycle defects from chromosomal instability. These experiments indicate that a homeostatic level of RB activity is essential for the self-renewal and the survival of human embryonic stem cells. 1 Department of Pediatrics, Stanford Medical School, Stanford, California 94305, USA. 2 Department of Genetics, Stanford Medical School, Stanford, California 94305, USA. 3 Institute for Stem Cell Biology and Regenerative Medicine, Stanford Medical School, Stanford, California 94305, USA. Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to J.S. -

Author Manuscript Faculty of Biology and Medicine Publication

Serveur Académique Lausannois SERVAL serval.unil.ch Author Manuscript Faculty of Biology and Medicine Publication This paper has been peer-reviewed but does not include the final publisher proof-corrections or journal pagination. Published in final edited form as: Title: Sexual dimorphism in cancer. Authors: Clocchiatti A, Cora E, Zhang Y, Dotto GP Journal: Nature reviews. Cancer Year: 2016 May Volume: 16 Issue: 5 Pages: 330-9 DOI: 10.1038/nrc.2016.30 In the absence of a copyright statement, users should assume that standard copyright protection applies, unless the article contains an explicit statement to the contrary. In case of doubt, contact the journal publisher to verify the copyright status of an article. Sexual dimorphism in cancer Andrea Clocchiatti1+, Elisa Cora2+, Yosra Zhang1,2 and G. Paolo Dotto1,2* 1Cutaneous Biology Research Center, Massachusetts General Hospital, Charlestown, MA 02129, USA; 2Department of Biochemistry, University of Lausanne, Epalinges, CH-1066, Switzerland + These authors contributed equally to the work * Corresponding author: G. Paolo Dotto email: [email protected] 1 Abstract The incidence of many cancer types is significantly higher in the male than female populations, with associated differences in survival. Occupational and/or behavioral factors are well known underlying determinants. However, cellular/molecular differences between the two sexes are also likely to be important. We are focusing here on the complex interplay that sexual hormones and sex chromosomes can have in intrinsic control of cancer initiating cell populations, tumor microenvironment and systemic determinants of cancer development like the immune system and metabolism. A better appreciation of these differences between the two sexes could be of substantial value for cancer prevention as well as treatment. -

In Vivo Studies Using the Classical Mouse Diversity Panel

The Mouse Diversity Panel Predicts Clinical Drug Toxicity Risk Where Classical Models Fail Alison Harrill, Ph.D The Hamner-UNC Institute for Drug Safety Sciences 0 The Importance of Predicting Clinical Adverse Drug Reactions (ADR) Figure: Cath O’Driscoll Nature Publishing 2004 Risk ID PGx Testing 1 People Respond Differently to Drugs Pharmacogenetic Markers Identified by Genome-Wide Association Drug Adverse Drug Risk Allele Reaction (ADR) Abacavir Hypersensitivity HLA-B*5701 Flucloxacillin Hepatotoxicity Allopurinol Cutaneous ADR HLA-B*5801 Carbamazepine Stevens-Johnson HLA-B*1502 Syndrome Augmentin Hepatotoxicity DRB1*1501 Ximelagatran Hepatotoxicity DRB1*0701 Ticlopidine Hepatotoxicity HLA-A*3303 Average preclinical populations and human hepatocytes lack the diversity to detect incidence of adverse events that occur only in 1/10,000 people. Current Rodent Models of Risk Assessment The Challenge “At a time of extraordinary scientific progress, methods have hardly changed in several decades ([FDA] 2004)… Toxicologists face a major challenge in the twenty-first century. They need to embrace the new “omics” techniques and ensure that they are using the most appropriate animals if their discipline is to become a more effective tool in drug development.” -Dr. Michael Festing Quantitative geneticist Toxicol Pathol. 2010;38(5):681-90 Rodent Models as a Strategy for Hazard Characterization and Pharmacogenetics Genetically defined rodent models may provide ability to: 1. Improve preclinical prediction of drugs that carry a human safety risk 2. -

Human Autologous Ipsc–Derived Dopaminergic Progenitors Restore Motor Function in Parkinson’S Disease Models

Human autologous iPSC–derived dopaminergic progenitors restore motor function in Parkinson’s disease models Bin Song, … , Jeffrey S. Schweitzer, Kwang-Soo Kim J Clin Invest. 2020;130(2):904-920. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI130767. Research Article Neuroscience Stem cells Graphical abstract Find the latest version: https://jci.me/130767/pdf RESEARCH ARTICLE The Journal of Clinical Investigation Human autologous iPSC–derived dopaminergic progenitors restore motor function in Parkinson’s disease models Bin Song,1,2 Young Cha,1,2 Sanghyeok Ko,1,2 Jeha Jeon,1,2 Nayeon Lee,1,2 Hyemyung Seo,1,2,3 Kyung-Joon Park,1 In-Hee Lee,4,5 Claudia Lopes,1,2 Melissa Feitosa,1,2 María José Luna,1,2 Jin Hyuk Jung,1,2 Jisun Kim,1,2,3 Dabin Hwang,1,2 Bruce M. Cohen,1 Martin H. Teicher,1 Pierre Leblanc,1,2 Bob S. Carter,6 Jeffrey H. Kordower,7 Vadim Y. Bolshakov,1 Sek Won Kong,4,5 Jeffrey S. Schweitzer,6 and Kwang-Soo Kim1,2 1Department of Psychiatry and 2Molecular Neurobiology Laboratory, McLean Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Belmont, Massachusetts, USA. 3Department of Molecular and Life Sciences, Hanyang University, Ansan, Korea. 4Department of Pediatrics, 5Computational Health Informatics Program, Boston Children’s Hospital, and 6Department of Neurosurgery, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts, USA. 7Department of Neurological Sciences, Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, Illinois, USA. Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a neurodegenerative disorder associated with loss of striatal dopamine, secondary to degeneration of midbrain dopamine (mDA) neurons in the substantia nigra, rendering cell transplantation a promising therapeutic strategy. -

Table S1 the Four Gene Sets Derived from Gene Expression Profiles of Escs and Differentiated Cells

Table S1 The four gene sets derived from gene expression profiles of ESCs and differentiated cells Uniform High Uniform Low ES Up ES Down EntrezID GeneSymbol EntrezID GeneSymbol EntrezID GeneSymbol EntrezID GeneSymbol 269261 Rpl12 11354 Abpa 68239 Krt42 15132 Hbb-bh1 67891 Rpl4 11537 Cfd 26380 Esrrb 15126 Hba-x 55949 Eef1b2 11698 Ambn 73703 Dppa2 15111 Hand2 18148 Npm1 11730 Ang3 67374 Jam2 65255 Asb4 67427 Rps20 11731 Ang2 22702 Zfp42 17292 Mesp1 15481 Hspa8 11807 Apoa2 58865 Tdh 19737 Rgs5 100041686 LOC100041686 11814 Apoc3 26388 Ifi202b 225518 Prdm6 11983 Atpif1 11945 Atp4b 11614 Nr0b1 20378 Frzb 19241 Tmsb4x 12007 Azgp1 76815 Calcoco2 12767 Cxcr4 20116 Rps8 12044 Bcl2a1a 219132 D14Ertd668e 103889 Hoxb2 20103 Rps5 12047 Bcl2a1d 381411 Gm1967 17701 Msx1 14694 Gnb2l1 12049 Bcl2l10 20899 Stra8 23796 Aplnr 19941 Rpl26 12096 Bglap1 78625 1700061G19Rik 12627 Cfc1 12070 Ngfrap1 12097 Bglap2 21816 Tgm1 12622 Cer1 19989 Rpl7 12267 C3ar1 67405 Nts 21385 Tbx2 19896 Rpl10a 12279 C9 435337 EG435337 56720 Tdo2 20044 Rps14 12391 Cav3 545913 Zscan4d 16869 Lhx1 19175 Psmb6 12409 Cbr2 244448 Triml1 22253 Unc5c 22627 Ywhae 12477 Ctla4 69134 2200001I15Rik 14174 Fgf3 19951 Rpl32 12523 Cd84 66065 Hsd17b14 16542 Kdr 66152 1110020P15Rik 12524 Cd86 81879 Tcfcp2l1 15122 Hba-a1 66489 Rpl35 12640 Cga 17907 Mylpf 15414 Hoxb6 15519 Hsp90aa1 12642 Ch25h 26424 Nr5a2 210530 Leprel1 66483 Rpl36al 12655 Chi3l3 83560 Tex14 12338 Capn6 27370 Rps26 12796 Camp 17450 Morc1 20671 Sox17 66576 Uqcrh 12869 Cox8b 79455 Pdcl2 20613 Snai1 22154 Tubb5 12959 Cryba4 231821 Centa1 17897 -

Table 2. Significant

Table 2. Significant (Q < 0.05 and |d | > 0.5) transcripts from the meta-analysis Gene Chr Mb Gene Name Affy ProbeSet cDNA_IDs d HAP/LAP d HAP/LAP d d IS Average d Ztest P values Q-value Symbol ID (study #5) 1 2 STS B2m 2 122 beta-2 microglobulin 1452428_a_at AI848245 1.75334941 4 3.2 4 3.2316485 1.07398E-09 5.69E-08 Man2b1 8 84.4 mannosidase 2, alpha B1 1416340_a_at H4049B01 3.75722111 3.87309653 2.1 1.6 2.84852656 5.32443E-07 1.58E-05 1110032A03Rik 9 50.9 RIKEN cDNA 1110032A03 gene 1417211_a_at H4035E05 4 1.66015788 4 1.7 2.82772795 2.94266E-05 0.000527 NA 9 48.5 --- 1456111_at 3.43701477 1.85785922 4 2 2.8237185 9.97969E-08 3.48E-06 Scn4b 9 45.3 Sodium channel, type IV, beta 1434008_at AI844796 3.79536664 1.63774235 3.3 2.3 2.75319499 1.48057E-08 6.21E-07 polypeptide Gadd45gip1 8 84.1 RIKEN cDNA 2310040G17 gene 1417619_at 4 3.38875643 1.4 2 2.69163229 8.84279E-06 0.0001904 BC056474 15 12.1 Mus musculus cDNA clone 1424117_at H3030A06 3.95752801 2.42838452 1.9 2.2 2.62132809 1.3344E-08 5.66E-07 MGC:67360 IMAGE:6823629, complete cds NA 4 153 guanine nucleotide binding protein, 1454696_at -3.46081884 -4 -1.3 -1.6 -2.6026947 8.58458E-05 0.0012617 beta 1 Gnb1 4 153 guanine nucleotide binding protein, 1417432_a_at H3094D02 -3.13334396 -4 -1.6 -1.7 -2.5946297 1.04542E-05 0.0002202 beta 1 Gadd45gip1 8 84.1 RAD23a homolog (S. -

Genetic Variability in the Italian Heavy Draught Horse from Pedigree Data and Genomic Information

Supplementary material for manuscript: Genetic variability in the Italian Heavy Draught Horse from pedigree data and genomic information. Enrico Mancin†, Michela Ablondi†, Roberto Mantovani*, Giuseppe Pigozzi, Alberto Sabbioni and Cristina Sartori ** Correspondence: [email protected] † These two Authors equally contributed to the work Supplementary Figure S1. Mares and foal of Italian Heavy Draught Horse (IHDH; courtesy of Cinzia Stoppa) Supplementary Figure S2. Number of Equivalent Generations (EqGen; above) and pedigree completeness (PC; below) over years in Italian Heavy Draught Horse population. Supplementary Table S1. Descriptive statistics of homozygosity (observed: Ho_obs; expected: Ho_exp; total: Ho_tot) in 267 genotyped individuals of Italian Heavy Draught Horse based on the number of homozygous genotypes. Parameter Mean SD Min Max Ho_obs 35,630.3 500.7 34,291 38,013 Ho_exp 35,707.8 64.0 35,010 35,740 Ho_tot 50,674.5 93.8 49,638 50,714 1 Definitions of the methods for inbreeding are in the text. Supplementary Figure S3. Values of BIC obtained by analyzing values of K from 1 to 10, corresponding on the same amount of clusters defining the proportion of ancestry in the 267 genotyped individuals. Supplementary Table S2. Estimation of genomic effective population size (Ne) traced back to 18 generations ago (Gen. ago). The linkage disequilibrium estimation, adjusted for sampling bias was also included (LD_r2), as well as the relative standard deviation (SD(LD_r2)). Gen. ago Ne LD_r2 SD(LD_r2) 1 100 0.009 0.014 2 108 0.011 0.018 3 118 0.015 0.024 4 126 0.017 0.028 5 134 0.019 0.031 6 143 0.021 0.034 7 156 0.023 0.038 9 173 0.026 0.041 11 189 0.029 0.046 14 213 0.032 0.052 18 241 0.036 0.058 Supplementary Table S3. -

A Role for Histone Modification in the Mechanism of Action of Antidepressant and Stimulant Drugs: a Dissertation

University of Massachusetts Medical School eScholarship@UMMS GSBS Dissertations and Theses Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences 2007-12-28 A Role for Histone Modification in the Mechanism of Action of Antidepressant and Stimulant Drugs: a Dissertation Frederick Albert Schroeder University of Massachusetts Medical School Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Follow this and additional works at: https://escholarship.umassmed.edu/gsbs_diss Part of the Amino Acids, Peptides, and Proteins Commons, Cells Commons, Enzymes and Coenzymes Commons, Genetic Phenomena Commons, Mental Disorders Commons, Nervous System Commons, and the Therapeutics Commons Repository Citation Schroeder FA. (2007). A Role for Histone Modification in the Mechanism of Action of Antidepressant and Stimulant Drugs: a Dissertation. GSBS Dissertations and Theses. https://doi.org/10.13028/7bk0-a687. Retrieved from https://escholarship.umassmed.edu/gsbs_diss/370 This material is brought to you by eScholarship@UMMS. It has been accepted for inclusion in GSBS Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of eScholarship@UMMS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Dissertation Presented by Frederick Albert Schroeder Submitted to the Faculty of the University of Massachusetts Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences Worcester, Massachusetts, USA in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY December 28, 2007 Program in Neuroscience A Role for Histone Modification in the Mechanism of Action of Antidepressant and Stimulant Drugs A Dissertation Presented By Frederick Albert Schroeder Approved as to style and content by: _____________________________________ Alonzo Ross, Ph.D., Chair of Committee _____________________________________ Pradeep Bhide, Ph.D., Member of Committee _____________________________________ Craig L. -

Watsonjn2018.Pdf (1.780Mb)

UNIVERSITY OF CENTRAL OKLAHOMA Edmond, Oklahoma Department of Biology Investigating Differential Gene Expression in vivo of Cardiac Birth Defects in an Avian Model of Maternal Phenylketonuria A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE IN BIOLOGY By Jamie N. Watson Edmond, OK June 5, 2018 J. Watson/Dr. Nikki Seagraves ii J. Watson/Dr. Nikki Seagraves Acknowledgements It is difficult to articulate the amount of gratitude I have for the support and encouragement I have received throughout my master’s thesis. Many people have added value and support to my life during this time. I am thankful for the education, experience, and friendships I have gained at the University of Central Oklahoma. First, I would like to thank Dr. Nikki Seagraves for her mentorship and friendship. I lucked out when I met her. I have enjoyed working on this project and I am very thankful for her support. I would like thank Thomas Crane for his support and patience throughout my master’s degree. I would like to thank Dr. Shannon Conley for her continued mentorship and support. I would like to thank Liz Bullen and Dr. Eric Howard for their training and help on this project. I would like to thank Kristy Meyer for her friendship and help throughout graduate school. I would like to thank my committee members Dr. Robert Brennan and Dr. Lilian Chooback for their advisement on this project. Also, I would like to thank the biology faculty and staff. I would like to thank the Seagraves lab members: Jailene Canales, Kayley Pate, Mckayla Muse, Grace Thetford, Kody Harvey, Jordan Guffey, and Kayle Patatanian for their hard work and support. -

Hoxb1 Controls Anteroposterior Identity of Vestibular Projection Neurons

Hoxb1 Controls Anteroposterior Identity of Vestibular Projection Neurons Yiju Chen1, Masumi Takano-Maruyama1, Bernd Fritzsch2, Gary O. Gaufo1* 1 Department of Biology, University of Texas at San Antonio, San Antonio, Texas, United States of America, 2 Department of Biology, University of Iowa, Iowa City, Iowa, United States of America Abstract The vestibular nuclear complex (VNC) consists of a collection of sensory relay nuclei that integrates and relays information essential for coordination of eye movements, balance, and posture. Spanning the majority of the hindbrain alar plate, the rhombomere (r) origin and projection pattern of the VNC have been characterized in descriptive works using neuroanatomical tracing. However, neither the molecular identity nor developmental regulation of individual nucleus of the VNC has been determined. To begin to address this issue, we found that Hoxb1 is required for the anterior-posterior (AP) identity of precursors that contribute to the lateral vestibular nucleus (LVN). Using a gene-targeted Hoxb1-GFP reporter in the mouse, we show that the LVN precursors originate exclusively from r4 and project to the spinal cord in the stereotypic pattern of the lateral vestibulospinal tract that provides input into spinal motoneurons driving extensor muscles of the limb. The r4-derived LVN precursors express the transcription factors Phox2a and Lbx1, and the glutamatergic marker Vglut2, which together defines them as dB2 neurons. Loss of Hoxb1 function does not alter the glutamatergic phenotype of dB2 neurons, but alters their stereotyped spinal cord projection. Moreover, at the expense of Phox2a, the glutamatergic determinants Lmx1b and Tlx3 were ectopically expressed by dB2 neurons. Our study suggests that the Hox genes determine the AP identity and diversity of vestibular precursors, including their output target, by coordinating the expression of neurotransmitter determinant and target selection properties along the AP axis. -

A Computational Approach for Defining a Signature of Β-Cell Golgi Stress in Diabetes Mellitus

Page 1 of 781 Diabetes A Computational Approach for Defining a Signature of β-Cell Golgi Stress in Diabetes Mellitus Robert N. Bone1,6,7, Olufunmilola Oyebamiji2, Sayali Talware2, Sharmila Selvaraj2, Preethi Krishnan3,6, Farooq Syed1,6,7, Huanmei Wu2, Carmella Evans-Molina 1,3,4,5,6,7,8* Departments of 1Pediatrics, 3Medicine, 4Anatomy, Cell Biology & Physiology, 5Biochemistry & Molecular Biology, the 6Center for Diabetes & Metabolic Diseases, and the 7Herman B. Wells Center for Pediatric Research, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, IN 46202; 2Department of BioHealth Informatics, Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis, Indianapolis, IN, 46202; 8Roudebush VA Medical Center, Indianapolis, IN 46202. *Corresponding Author(s): Carmella Evans-Molina, MD, PhD ([email protected]) Indiana University School of Medicine, 635 Barnhill Drive, MS 2031A, Indianapolis, IN 46202, Telephone: (317) 274-4145, Fax (317) 274-4107 Running Title: Golgi Stress Response in Diabetes Word Count: 4358 Number of Figures: 6 Keywords: Golgi apparatus stress, Islets, β cell, Type 1 diabetes, Type 2 diabetes 1 Diabetes Publish Ahead of Print, published online August 20, 2020 Diabetes Page 2 of 781 ABSTRACT The Golgi apparatus (GA) is an important site of insulin processing and granule maturation, but whether GA organelle dysfunction and GA stress are present in the diabetic β-cell has not been tested. We utilized an informatics-based approach to develop a transcriptional signature of β-cell GA stress using existing RNA sequencing and microarray datasets generated using human islets from donors with diabetes and islets where type 1(T1D) and type 2 diabetes (T2D) had been modeled ex vivo. To narrow our results to GA-specific genes, we applied a filter set of 1,030 genes accepted as GA associated.