African Women and Icts (Investigating Technology, Gender

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Women's Political Voice in Morocco

April 2015 Case Study Summary Women’s empowerment and political voice • Women’s representation in parliament THE ROAD TO REFORM has increased dramatically, from 1% in 2003 to 17% today. Women’s political voice in • Morocco’s 2004 Family Code is one of the Morocco most progressive in the Arab world. • In 1993, Morocco ratified an international Clare Castillejo and Helen Tilley agreement on gender equality that has provided leverage for further progress in domestic legislation. • The 2011 constitution asserts women’s equal rights and prohibits all discrimination, including gender discrimination. • Data on the spending of public funds is now gender-disaggregated data and so can be used to inform lobbying campaigns to improve outcomes for women and girls. • Women’s health and social outcomes have improved dramatically: the fertility rate is now one of the lowest in the region; the maternal mortality rate fell by two-thirds in just two decades; girls’ primary school enrolment rose from 52% in 1991 to 112% in 2012 (due to re-enrolment); and just under 23% of women are in formal employment (2011). This and other Development Progress materials are available at developmentprogress.org Development Progress is an ODI project that aims to measure, understand and communicate where and how progress has been made in development. ODI is the UK’s leading independent Moroccan women gather at an event commemorating International Women’s Day. Photo: © UN Women / Karim think tank on international development Selmaouimen. and humanitarian issues. Further ODI materials are available at odi.org.uk developmentprogress.org Why explore women’s political voice in uprisings of 2011 led Morocco’s King Mohammad VI Morocco? to adopt wide-ranging constitutional reforms, including Women’s political mobilisation in Morocco illustrates how an elected government and an independent judiciary, excluded and adversely incorporated groups can achieve these reforms have had paradoxical effects for women. -

1 Institutional Changes in the Maghreb: Toward a Modern Gender

Institutional Changes in the Maghreb: Toward a Modern Gender Regime? Valentine M. Moghadam Professor of Sociology and International Affairs Northeastern University [email protected] DRAFT – December 2016 Abstract The countries of the Maghreb – Algeria, Morocco, and Tunisia – are part of the Middle East and North Africa region, which is widely assumed to be resistant to women’s equality and empowerment. And yet, the region has experienced significant changes in women’s legal status, political participation, and social positions, along with continued contention over Muslim family law and women’s equal citizenship. Do the institutional and normative changes signal a shift in the “gender regime” from patriarchal to modern? To what extent have women’s rights organizations contributed to such changes? While mapping the changes that have occurred, and offering some comparisons to Egypt, another North African country that has seen fewer legal and normative changes in the direction of women’s equality, the paper identifies the persistent constraints that prevent both the empowerment of all women and broader socio-political transformation. The paper draws on the author’s research in and on the region since the early 1990s, analysis of patterns and trends since the Arab Spring of 2011, and the relevant secondary sources. Introduction The Middle East and North Africa region (MENA) is widely assumed to be resistant to women’s equality and empowerment. Many scholars have identified conservative social norms, patriarchal cultural practices, and the dominance of Islam as barriers to women’s empowerment and gender equality (Alexander and Welzel 2011; Ciftci 2010; Donno and Russett 2004; Fish 2002; Inglehart and Norris 2003; Rizzo et al 2007). -

Knowledge Management for Culture and Development: MDG-F Joint

AARABRAB STATESSTATES AFRICA LATIN AMERICA South East EUROPE ASIA ARAB STATES CULTURE AND DEVELOPMENT CULTURE CULTURE AND DEVELOPMENT CULTURE AND DEVELOPM DEVELOPMENTCULTURE CULTURE AND DEVELOPMEN CULTURE AND DEVELO CULTURE AND DEVELOPMENT MOROCCO MOROCCO MDG-F JointProgrammes PALESTINIAN TERRITORY PALESTINIAN in EGYPT, MAURITANIA, EGYPT, and the OCCUPIED OCCUPIED PALESTINIAN TERRITORY MOROCCO EGYPT MAURITANIA Culture and Development in the Arab States Sharing centuries-old vast cultural, religious, linguistic and historical heritage, the Arab States have long placed their heritage at centre stage, focusing on its pro- motion for tourism as a path to development. The recent Arab Spring movement has indicated a wave of change that has swept the Arab region, where people are calling for new solutions that will bring peace and development. In this ground-breaking transition taking place in the Arab region, culture is a powerful source of hope and identity, a motor of social and economic development, playing a key role in reconstruction and in laying the groundwork for a culture of peace. Within this context, the MDG-F Culture and Development Joint Programmes The MDG-F Joint Programmes on Culture implemented in the Arab States greatly contribute to a holistic vision of development and Development in the Arab States in which the role of culture is highly valued. Focusing particularly on safeguarding > 4 Joint Programmes: Egypt, Mauritania, Morocco and occupied Palestinian territory (oPt) the diverse cultural heritage and using it as an enabler -

Founding Voices of Women's and Gender Studies in Uganda

Journal of International Women's Studies Volume 21 Issue 2 Articles from the 5th World Conference Article 2 on Women’s Studies, Bangkok, Thailand April 2020 A Room, A Chair, and A Desk: Founding Voices of Women’s and Gender Studies in Uganda Adrianna L. Ernstberger Marian University Follow this and additional works at: https://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws Part of the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Ernstberger, Adrianna L. (2020). A Room, A Chair, and A Desk: Founding Voices of Women’s and Gender Studies in Uganda. Journal of International Women's Studies, 21(2), 4-16. Available at: https://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws/vol21/iss2/2 This item is available as part of Virtual Commons, the open-access institutional repository of Bridgewater State University, Bridgewater, Massachusetts. This journal and its contents may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. ©2020 Journal of International Women’s Studies. A Room, A Chair, and A Desk: Founding Voices of Women’s and Gender Studies in Uganda By Adrianna L. Ernstberger1 Abstract This paper studies the birth and development of women’s and gender studies in Uganda. I conducted this research as part of a doctoral thesis on the history of women’s and gender studies in the Global South. Using feminist and standpoint theories, much of the research includes oral histories gathered over the course of three years of field work in Uganda. -

Female Educators in Uganda

Female Educators in Uganda UNDERSTANDING PROFESSIONAL WELFARE IN GOVERNMENT PRIMARY SCHOOLS WITH REFUGEE STUDENTS Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies & Creative Associates International SPRING 2019 | SAIS WOMEN LEAD PRACTICUM PROGRAM Table of Contents TABLE OF FIGURES ............................................................................................................... III ABOUT THE AUTHORS ......................................................................................................... IV ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ....................................................................................................... V ACRONYMS ....................................................................................................................... VI MAP OF UGANDA............................................................................................................. VII EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ..................................................................................................... VIII 1. INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................. 10 2. BACKGROUND AND LITERATURE REVIEW...................................................................... 13 3. METHODOLOGY & RESULTS ........................................................................................... 18 METHODOLOGY .......................................................................................................................... 18 ANALYSIS ................................................................................................................................... -

Uganda: Violence Against Women and Information and Communication Technologies

Uganda: Violence against Women and Information and Communication Technologies Aramanzan Madanda, Berna Ngolobe and Goretti Zavuga Amuriat1 Association for Progressive Communications (APC) September 2009 Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 Unported creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/ 1Goretti Zavuga Amuriat is a Senior Gender and ICT Policy Program Officer at Women of Uganda Network (WOUGNET). She spearheadsa campaign for integrating gender into ICT policy processes in Uganda. She is also project coordinator of the Enhancing Income Growth among Small and Micro Women Entrepreneurs through Use of ICTs initiative in Uganda. URL: www.wougnet.org Berna Twanza Ngolobe is an Advocacy Officer of the Gender and ICT Policy Advocacy Program, Women of Uganda Network (WOUGNET) URL: www.wougnet.org Aramanzan Madanda is currently finalising a PhD researching adoption of ICT and changing gender relations using the example of computing and mobile telephony in Uganda. He is also ICT Programme Coordinator in the Department of Women and Gender Studies, Makerere University Uganda. Email: [email protected], URL www.womenstudies.mak.ac.ug. Table of Contents Preface.........................................................................................................................3 Executive summary........................................................................................................4 1. Overview.............................................................................................................................6 -

Uganda and Rwanda

Women, Peace and Security: Practical Guidance on Using Law to Empower Women in Post-Conflict Systems Best Practices and Recommendations from the Great Lakes Region of Africa CASE STUDIES UGANDA AND RWANDA Julie L. Arostegui Veronica Eragu Bichetero © 2014 Julie L. Arostegui and WIIS. All rights reserved. Women in International Security (WIIS) 1111 19th Street, NW 12th Floor Washington, DC 20036 Email: [email protected] Website: http://wiisglobal.org UGANDA HISTORY OF THE CONFLICT Uganda has had a history of civil conflict since its independence from the United Kingdom in 1962 - triggered by political instability and a series of military coups between groups of different ethnic and ideological composition that resulted in a series of dictatorships. In 1966, just four years after independence, the central government attacked the Buganda Kingdom, which had dominated during British rule, forced the King to flee, abolished traditional kingdoms and declared Uganda a republic. In 1971 Army Commander Idi Amin Dada overthrew the elected government of Milton Obote, and for eight years led the country through a regime of terror under which many people lost their lives. Amin was overthrown in 1979 by rebel Ugandan soldiers in exile supported by the army of TanZania. Obote returned to power through the 1980 general elections, ruling with army support. In 1981 a five-year civil war broke out led by the current president, Yoweri Kaguta Museveni and the National Resistance Army (NRA), protesting the fraudulent elections. Known as the Ugandan Bush War, the conflict took place mainly in an area of fourteen districts north of Kampala that was known as the Luwero Triangle. -

Chapter 1 Women's Participation in the Labour Market And

1. Women’S participation in the labour marKet and entrepreneurship in selecteD MENA countries – 25 Chapter 1 Women’s participation in the labour market and entrepreneurship in selected MENA countries This chapter presents an overview of women’s educational attainment, participation in the labour market and involvement in entrepreneurship in the six countries under review – Algeria, Egypt, Libya, Jordan, Morocco and Tunisia. It examines women’s engagement in the economies of the six countries as compared to men’s participation as well as to women’s economic involvement in other parts of the world. The chapter also seeks to better understand the main features defining women’s economic status and the different characteristics of men and women in employment and entrepreneurship. WOMEN’S ECONOMIC EMPOWERMENT IN SELECTED MENA COUNTRIES – © OECD 2017 26 – 1. Women’S participation in the labour marKet and entrepreneurship in selecteD MENA countries Introduction There is a striking gap between women’s improved education and their limited participation in economic activities in Algeria, Egypt, Jordan, Libya, Morocco and Tunisia. Despite the substantial narrowing of the gender gap in education, the percentage of women in the total employed population in the six countries is among the lowest in the world, at 17.9%, compared with the world average of 47.1% (World Development Indicators, 2014). Female labour-force participation in these countries ranges from 15.4% in Algeria to 30% in Libya. At the same time, a dramatic gap between labour supply and demand in the female workforce has been creating high levels of unemployment, in particular among young educated women. -

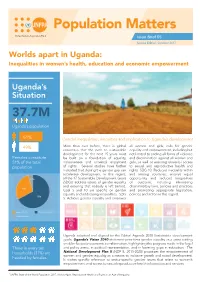

Uganda's Situation

United Nations Population Fund Issue Brief 05 Worlds apart in Uganda: Inequalities in women’s health, education and economic empowerment Uganda’s Situation 37.7M Uganda’s population 51% Gender inequalities, inequities and implication to Uganda’s development 49% More than ever before, there is global all women and girls, calls for gender consensus that the path to sustainable equality and empowerment, including but development for the next 15 years must not limited to ending all forms of violence Females constitute be built on a foundation of equality, and discrimination against all women and 51% of the total inclusiveness and universal enjoyment girls, as well as ensuring universal access population of rights. Several studies have further to sexual and reproductive health and indicated that closing the gender gap can rights. SDG 10: Reduced inequality within accelerate development. In this regard, and among countries; ensures equal 3.7% all the 17 Sustainable Development Goals opportunity and reduced inequalities (SDGs) address issues of gender equality of outcome, including eliminating and ensuring that nobody is left behind. discriminatory laws, policies and practices 23% Goal 5 and 10 are specific on gender and promoting appropriate legislation, equality and addressing inequalities. SDG policies and action in this regard. 55% 5: Achieve gender equality and empower Youth (18-30) Children below 18 Older persons Uganda adopted and aligned to the Global Agenda 2030 Sustainable development goals. Uganda’s Vision 2040 statement prioritizes gender equality as a cross-cutting enabler for socio-economic transformation, highlighting the progress made in the legal Three in every ten and policy arena, in political representation, and in lowering gaps in education. -

Legal Discrimination 1

Legal Discrimination 1 Legal Discrimination in Morocco and the United States Kathryn Snyder, Allie Lake, Taylor Pierson, Tyler Munn, Ahdiam Berhe, Davaria Harris, Nizar Krari, Omar Kharriche, Ayoub Lansi Department of Public Health, Indiana University PBHL-S 635: Biosocial Approach to Global Health Dr. Turman April 27, 2020 Legal Discrimination 2 Abstract Legal discrimination is defined as “where people have created and enforce laws to uphold [...] discrimination” (Krieger, 2014, p. 648). Legal discrimination has direct effects on the health of women and girls in Morocco and the United States. Two cases of legal discrimination and their connection to adverse health outcomes for women and girls will be explored for each country. In Morocco, these are the discriminatory inheritance law and the widespread lack of enforcement and awareness of laws advancing women’s rights. In the United States, the issues identified here are access to reproductive healthcare and paid maternity leave. Evidence based interventions and actions for each government to take to advance the status of women will be discussed. In Morocco, it is recommended that the discriminatory inheritance law be repealed. Additionally, it is recommended that Morocco provide gender equality protocols for its judicial system and implement widespread access to legal aid through use of community-based paralegals. Lastly, it is recommended that Morocco adopt a definitive and comprehensive definition of domestic violence and revise their current legislation criminalizing gender-based violence to designate roles and responsibilities for upholding the law to specific institutions. In the United States, it is recommended that the government pass a law providing paid maternity leave for all workers. -

Women and the Web Bridging the Internet Gap and Creating New Global Opportunities in Low and Middle-Income Countries

Women and the Web Bridging the Internet gap and creating new global opportunities in low and middle-income countries Women and the Web 1 For over 40 years Intel has been creating technologies that advance the way people live, work, and learn. To foster innovation and drive economic growth, everyone, especially girls and women, needs to be empowered with education, employment and entrepreneurial skills. Through our long-standing commitment to helping drive quality education, we have learned first-hand how investing in girls and women improves not only their own lives, but also their families, their communities and the global economy. With this understanding, Intel is committed to helping give girls and women the opportunities to achieve their individual potential and be a power for change. www.intel.com/shewill For questions or comments about this study, please contact Renee Wittemyer ([email protected]). Dalberg Global Development Advisors is a strategy and policy advisory firm dedicated to global development. Dalberg’s mission is to mobilize effective responses to the world’s most pressing issues. We work with corporations, foundations, NGOs and governments to design policies, programs and partnerships to serve needs and capture opportunities in frontier and emerging markets. www.dalberg.com For twenty-five years, GlobeScan has helped clients measure and build value-generating relationships with their stakeholders, and to work collaboratively in delivering a sustainable and equitable future. Uniquely placed at the nexus of reputation, brand and sustainability, GlobeScan partners with clients to build trust, drive engagement and inspire innovation within, around and beyond their organizations. www.globescan.com Women and the Web 3 FOREWORD BY SHELLY ESQUE Over just two decades, the Internet has worked a thorough revolution. -

British Women Travellers in Algeria, Tunisia, and Morocco, 1850–1930

Athens Journal of Mediterranean Studies- Volume 6, Issue 4, October 2020 – Pages 279-292 British Women Travellers in Algeria, Tunisia, and Morocco, 1850–1930 By Amina Marzouk Chouchene* Algeria, Tunisia, and Morocco attracted many British women travellers mainly during the second half of the nineteenth century and the early decades of the twentieth. Although their number was smaller than that of their male colleagues, these women were attracted to the so-called North African Barbary States and left interesting accounts of their journeys. They recorded their perceptions of the various regions they visited and the people they encountered. Through examining a corpus of travelogues, this article explores these women’s reasons for travelling to and writing about the three North African countries and their responses to the new lands. The article reveals that these women travellers enjoyed the climates, mineral springs, and natural landscapes of these countries. Keywords: Algeria, Tunisia, Morocco, British women travellers, tourism Introduction In the second half of the nineteenth century, the presence of British women travellers in Algeria, Tunisia, and Morocco became much more remarkable. This is evident through the proliferation of women’s travelogues describing their journeys to the so-called Barbary States of North Africa. This trend contrasts with the eighteenth century during which most travellers were males. British women’s travels in the three North African countries were enabled, to a large extent, by the political stability following the French Revolution and the Napoleonic wars in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries and the improved transportation. The introduction of new means of transport such as steamships and railways facilitated the movement of women travellers to different parts of the world including Algeria, Tunisia, and Morocco.